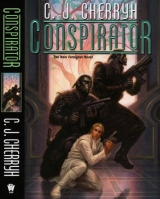

Текст книги "Conspirator"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

He loved this hallway. It had something quite rare in atevi architecture, a technique perhaps borrowed, centuries ago, from Mospheirans. The wing ended in a stained-glass window, a huge affair: staff had lit the outside lanterns, which only hinted at its colors. He looked forward to morning, when its smoldering reds and blues and golds would bloom into pastels and light, a rare representation of an actual object—atevi art was given to patterns completely overwhelming any hint of a person or a tree or a landscape. This was indisputably a tree, with branches more natural than patterned, and he loved the piece. He’d almost, of all things, forgotten it; and the little he could see of it was precious to him, the final touch on his homecoming. He loved this whole place—small, as lordly houses went, cozy. He found himself completely at peace as he entered the dining room, smelled the savory aromas wafting in from the service hall, and met three familiar faces—serving staff he and Banichi and Jago had known and trusted for years.

“Nadiin-ji,” he said warmly. “So very good to see you.”

“Nandi.” Bows. Equally warm greetings. “Will a before-dinner drink be in order?”

He named it, an old favorite, perfectly safe.

And saw those three calm expressions change to shock, as Toby entered—with Barb clinging to his arm and with her blonde curly head pressed against his shoulder. Laughing.

His face must have registered almost the same shock as his servants. Toby stopped, taking the cue. Barb left Toby and came and hooked her arm into his, tugging at him as he stood fast.

“Bren. This place is so marvelous.”

“Thank you,” he said, and disengaged his arm enough to bow slightly, to Toby, then, in complete disengagement, to her. He said, then, soberly: “Customs are different here. People don’t touch. Forgive me.”

“Well, but we’re family,” Toby said, trying to cover it all.

“So are my staff,” Bren said shortly. It was an unhappy moment. He saw resentment in his brother, beyond just a natural embarrassmentc old, old issue, the matter of atevi culture, which, the more he had taken it on, had separated him further and further from Tobyc and their mother. And thatwas the sore point. “Sorry, Toby. Sit down. What will you drink? No beer, I’m afraid. We have vodka and some import wine. Vodka and shebai is good. I recommend it.” He was talking too much, too urgently. He was on the verge of embarrassing his staff as well as himself, doing their job instead of translating. And he resented the situation Barb had put him in. “Take the shebai.”

“Sure,” Toby said. “Barb?”

“White wine.”

He turned and translated for the staff. “Nand’ Toby will enjoy shebai. Barb-daja will have the pale wine, nadiin-ji. Forgive them.” He saw, in the tail of his eye, Barb reattaching herself to Toby, and he didn’t know what to do about it.

Neither did his staff, who would have seated them.

“Toby. Barb. Take those endmost seats, if you please. Toby. Please.”

“I think he means no touching,” Toby said to Barb, attempting humor. Barb actually blushed vivid pink, and shot him a look.

Jago shot a look back, Bren caught that from the tail of his eye as he turned to sit down, and as he took his seat at the head of the table, Banichi simply walked to Toby’s end of the dining room, in the ample space the reduced table size allowed, and stood there, looming over the couple while a very embarrassed servant moved to seat first Toby, who had started to seat Barb himself. It was a thoroughly bollixed set of social signalsc and dammit, Toby had guested here. Toby knew better.

“Toby always sits first,” Bren said in Mosphei’, to Barb. He didn’t add that Toby, as his brother, outranked Barb—and that the staff’s opinion of Barb’s social standing was surely sinking faster by the minute. He could imagine the talk in the kitchenc questions as to whether Toby had brought an entertainer—and a stupid one, at that—to a formal dinner under his brother’s very proper roof.

It was a social disaster and he was furious at Barb: Toby clearly knew better; and Barb was not that unread—but no, Barb decided she could push the whole atevi social system, here, under his roof, to assert herself—which Toby might or might not read the same way, and there was no way on earth he was going to convince Toby what her game really was. There was no way he could bring it up at the dinner table, for damned sure.

There was one way to defuse it gracefully: diplomacy, the art of saying what one didn’t believe, in order to swing the behavior toward what one wanted: guidance, more than lying. So he needed to have had a special talk with them. He clearly needed to have a talk with them, but not now, with personal embarrassment in the mix. It was likely Banichi and Jago would have that talk—by now, he was sure they intendedto have it in Mosphei’ the minute they had the chance, and logically they wouldhave had it immediately with Toby’s personal guard, if Toby had arrived with onec which, of course, he hadn’t—unless one counted Barb. It was the sort of social glitch-up and attitude that had led to the War of the Landing. Humans were sure atevi would adapt to their very friendly way with just enough encouragement. Atevi—who didn’t even have a word for friendship– assumed humans, who seemed so intelligent, would eventually learn civilized manners. Atevi assumed since they owned the planet, humans were in theirhouse, while humans considered that they could just naturally get atevi to relax the rules, since their motives were the bestc or for mutual profit.

“Drinks will arrive momentarily,” Bren said quietly. “I do owe you both a profound apology for not mentioning certain things beforehand. This is a formal occasion. It’s my fault.”

“You’ve been here too long,” Toby said, and it came out like a retort.

“I live here,” Bren said, just a trifle unwisely: he knew that once he’d said it, and added, the truth: “I won’t likely live on Mospheira again. So yes, I’ve changed.” That, for Barb, just a trifle pointedly, and for Toby, with gentler intent: “I’ve done things a certain way so long I’m afraid I’ve lost part of my function as a translator, because I truly should have translated the situation. An atevi house is never informal—but tonight is official. Barb, forgive me, you have to keep a respectful distance from each other except in the bedroom. If someone does something for you in your quarters, bow your head just slightly and say mayei-ta. About the seating: Toby takes precedence because he’s my relative and this is my house; gender has no part at all in the etiquette.”

“You mean we just shocked them,” Barb said.

“Profoundly,” Bren said mercilessly. “The same as if they’d surprised you in bed.” He actually succeeded in shocking her– not in what he said; but where he said it. And the drinks were arriving. He smiled at Barb with edged politesse, and wiped the hardness off his face in a nod to his staff. “Mayei-tami, nadiin-ji. Sa heigieta so witai so kantai.”

Which was to say, “Thank you, esteemed people. Your service is timely and very considerate.”

“Mayei-ta,” Barb said with a little nod, on getting her drink. “Mayei-ta,” Toby muttered, “nadiin-ji.”

“A amei, nandi.” This from the young server, who did notaccord Barb a notice, except to use the dual-plus-one, to make the number fortunate, and who paid a second, parting bow to Bren, a unity of one. He left via the serving door, and Jago turned smartly and tracked the young person straight out of the dining room, probably to deliver a certain explanation to the staffc

What, that the lord’s brother-of-the-same-house was attempting to civilize the human he had brought under the lord’s roof? That Toby was likely equally embarrassed, put on the spot by the lady, and was trying not to make an issue of it?

Probably not. Jago was nota diplomat. The talk probably ran something like: “Bren-nandi tolerates this woman because his brother and this woman recently risked their lives in the aiji’s service. The lord will deal with his brother, who will, one hopes, deal forcefully with this woman.”

Certainly Jago was back in just about that amount of time, and took up her position on the other side of the serving door, stiffly formal.

“Good,” Toby had said, meanwhile, regarding the drink, and Barb had agreed.

“How is the aiji’s household?” Toby asked. “Is that all right to ask?”

“Perfectly in order,” Bren said in some relief, and relaxed a little, with a sip of his drink. “Everyone is in good health. Nand’ Cajeiri is back with his father and mother, the relatives have mostly gone back to the country– Ihave nowhere to live, since I’ve been using Lord Tatiseigi’s apartment while he was patching up the damage to his estate, and he’s on his way back to the capital.”

“Well, I’dthink you’d be a priority,” Barb said. “I don’t know why you’re shunted out to the coast.”

“I’m a very high priority,” he said equably, “but it’s his apartment. The aiji himself is still living in his grandmother’s apartment, since his residence was shot up; and mine just happens to be full of Southerners at the moment. It’s tangled. A defunct clan, the Maladesi, owned both this estate and the Bujavid apartment, both of which came to me; but they have remote relatives, the Farai, who claim to have opened the upper doors to the aiji on his return—someone did, for certain—never mind that Tabini was actually coming up from the basement; but the doors did open to a small force that was coming up the hill. It’s the thought that counts, so to say, and therefore there’s a debt. The Farai had taken over my apartment, in my absence, and they’re still in there, politely failing to hear any polite suggestion they move out.”

“And the aijican’t move them?” Toby said. “I’d think he could at least offer them a trade. Or you some other apartment.”

“Well, that’s easier said than done. Apartments in the Bujavid can’t be had: it’s on a hill, there’s no convenient way to build on, though some have suggested doing away with legislative offices as a possibility– The point is, there’s not only no place to put me, there’s no room for half a dozen other clans that had rather have that honor—some of them really deserving it. There’s a certain natural resentment among the conservatives that Istand as high as I do, so that’s a touchy point that publicity just doesn’t help. Andthe Farai are Southern, which is its own problem.”

“Aren’t they the batch that just rebelled?”

“Related to them. Neighboring district. Their opening the doors to the aiji was a clear double cross of Southern interests, but since Murini’s Southern allies suffered a rash of assassinations, and since clans have changed leadership, the whole political geography down there has shifted—somewhat. Understand: Tabini-aiji is Ragi atevi. North central district. The South is Marid atevi, different dialect, different manners, four different ethnic groups, and historically independent. They were dragged kicking and screaming into the aishidi’tat by Tabini’s grandfather; they’ve rebelled three times, generally been on the other side of every issue the aiji supports, but they are economically important to the continent—major fishing industry, southern shipping routes: fishing is important.”

“Nonseasonal.” Toby knew that: certain foods could only be eaten in certain seasons, but most fishes had no season, and were an important mainstay in the diet—one of the few foods that could be legitimately preserved.

“Nonseasonal, and essential. If it weren’t for the fishing industry, the seasonal economy would be difficult, to say the least. So the aishidi’tat needs the South, the Marid. Needs all that association, as it needs the western coast. All very important. And by promoting the Farai in importance—however inconvenient to me—the aiji can make important inroads into the Southern political mindset. You always handle the South with tongs, because, however annoying the Marid leadership has been to the aishidi’tat, the people areloyal to their own aijiin. The Farai are Senjin Marid, as opposed to the Tasaigin Marid and the Dojisigin Marid. They’re northernmost of the four Southern Associations, and they appear to have switched sides.”

“Four Associations,” Toby said. “Isn’t that an infelicity?”

“Extremely,” Bren said. “In all senses. It’s unstable as hell. Double crosses abound in that relationship. One clan or the other is always playing for power—lately mostly the Tasaigi, which swallowed up the fifth Association, the islands, which has no living clan, and has the most territory. The Tasaigi argue that one strong aiji in theirAssociation, dominating the other clans, makes a felicitous arrangement. The Senji, the Dojisigi, the Dausigi—all have their own opinions, but the Tasaigi usually lead. Except lately. Since the Tasaigi’s puppet Murini fell from power, the Farai of the Senji district seem to be bidding to control the South.”

“The ones in your apartment.”

“Exactly. The Tasaigin Marid has produced three serious conspiracies to take powerc all failing. If Tabini-aiji should actually give Farai that apartment permanently—that nice little honor of residing inthe halls of power– Well, the theory is that the Farai, and thus the Senjin Marid, might become a Southern power that can actually be dealt with, which would calm down the South. I personally don’t think it’s going to work. But in one sense, my apartment could end up being a small sacrifice to a general peace—until the Farai revert to Southern politics as usual; or until someone in the South takes out a Contract on them. Which could happen next week, as the wind blows. What’s a current security nightmare is the fact that my old apartment shares a small section of wall with Tabini’s proper apartment. So that’s being fixed—in case the Farai presence there becomes permanent. Who knows? It could. At least they didn’t make a claim on this estate. I’d be veryupset if that happened.”

“It’s very beautiful,” Barb said.

“Palatial,” Toby said. “I can only imagine what your place in the Bujavid must have looked like.”

A little laugh. An easier feeling. “Well, Najida’s a little smaller, actually. And the rooms here all let out into a hall that I alsoown, which always feels odd to me. I think this whole house would fit inside the aiji’s apartment in the Bujavid.” He saw a little tilt of Banichi’s head, Banichi being in position to have a view down the serving hall, and read that as a signal. “Staff’s preparing to serve the first course. And with apologies, let me give you a fast primer on formal dinners: no business, no politics, nothing but the lightest, most pleasant conversation during the dinner itself, nothing heavy until we retire for after-dinner drinks. We keep it light, keep it happy, take modest bites, at a modest tempo, and don’t try to signal staff for drink: you’ll embarrass them. They’ll be on an empty glass in a heartbeat. A simple open hand at the edge of the plate will signal them you want a second helping of a dish: be careful, or you willget one; and if you see them give me a flat palm for a signal, that means they’re running out of a particular course and want to advance the service, so don’t ask for seconds then, or they’ll be scrambling back there to try to produce an extra, probably one of their own meals. There’ll be an opening course, a mid-course, a meat presentation, and a dessert, different wine with each, so expect that. And somewhere during the meat presentation the cook will look in, we’ll invite him in, praise the dish—it’s going to be spectacular, I’m sure—and thank him and the staff. There’s going to be much more food than you can possibly afford seconds of, if you want my advice. And then we’ll thank the staff again, and get up and go to the parlor for drinks and politics, if you like.”

They took that advisement in good humor, at least. It forecast at least a patch on things.

Barb, however, was on her own agenda since she’d arrived at the front door. He’d known her long enough to spot that.

And being Barb, she didn’t think her agenda through all the way to the real end, just the immediate result she fantasized having. She wanted to make him uncomfortable: she wanted him to acknowledge he’d been utterly wrong to drop her. The fact it could have international repercussions was so far off her horizon it was in another universe. The possibility of setting him and Toby permanently at odds, well, that just wouldn’t happen, in her thinking, because she controlled everything and that wasn’t the way she planned.

That was how she’d ended up marrying the dullest man on Mospheira, to get back at him, and had an emotional crisis when it turned out he wished her well and walked off; it was how she’d spent years of her life taking care of his and Toby’s mother, once she got her divorce—because she was just essential to their family, wasn’t she?

In point of fact, if he hadn’t had to run the gauntlet of Barb’s emotions to get to his mother’s bedside, maybe he’d have found a way over to the island more often—

No, that was a lie. Circumstances a lot more potent than Barb’s angst had made him unavailable and finally sent him off the planet and into a two-year absence. So that hadn’t been Barb’s fault, wasn’t his, wasn’t Toby’s fault, either, but it had done for Toby’s marriage, all the same.

And where did Barb go after Toby’s divorce—hell, beforethe divorce? Barb had been at their mother’s place. So had Toby. They’d both been at the hospital all day. Toby’s wife Jill had taken the kids and bailed.

He didn’t want to think about that, not the whole few days Toby and Barb might be here. He’d be damned sure there wasn’t another scene. He had to talk to Toby, was what. There was no use talking to Barb. That was precisely what she wanted.

Hewas precisely what she wanted, because he’d been too distracted to give a damn when she’d left him. There was the lasting trouble.

He put on his best diplomatic smile while staff served the first course, eggs floating in sauce; and didn’t let himself think too far down the course of events. They’d get out on the boat, they’d do some fishing. There was no real reason to have a deep heart-to-heart with Toby on the matters of atevi manners, Barb, or the particular reasons he hadn’t been there when their mother needed him. Fact was, Barb was going to do what Barb intended to do, and there was no way to warn a man off a personal relationship and stay on good terms with him. They could put a patch on it and smile at each other, fishing would keep them all busy, wear them out, and they could do some beachside fish-roasting and keep the issues between him and Toby and him and Barb off the agenda entirely until it was time for the formal farewell dinner.

They could get through that, too. With luck, they never would have to discuss the reasons for their problems at all.

Chapter 3

« ^ »

Great-uncle Tatiseigi was coming back to the Bujavid, and that was by no means good, in Cajeiri’s estimation.

But Great-grandmother was coming with him, and that waswelcome news. Great-grandmother understood him better than his parents did, and better still, Great-grandmother could make his father listen, being Father’sgrandmother, and powerful in her own right.

Things were definitely looking up, almost making up for his losing nand’ Bren—who hadn’t been able to talk to him before he left, not really. Great-grandmother’s major domo, Madiri, was hurrying about, berating tardy staff. Cajeiri’s own door guards, Temien and Kaidin—his wardens, in his own estimation—who were on loan from Uncle, were in their best uniforms; his mother and father were dressing for the aiji-dowager’s arrival– it being her apartment they all were living in.

And very possibly—Cajeiri thought—they might soon be in the same case as nand’ Bren, having to move out to let manihave her apartment back, the same as nand’ Bren had had to move out to let Uncle Tatiseigi have his. They might have to move out to the hunting lodge out at Taiben, which was where his own personal staff, Antaro and Jegari, had come from.

And that would be attractive: Taiben lodge was bigger, and he would have much more room; and there was the woods; and there was riding mecheiti and running about with Antaro and Jegari, who would be absolutely afire to show him thingsc that would be good.

Maybe his tutor would stay in the capital. That would be even better.

But he had ever so much rather be left here in Shejidan, in the Bujavid, and live in mani’s apartment, and be with her, the way he’d grown up—well, several years of his growing up, but the best years, the years that really, truly mattered: his time in the country, his little sojourn at mani’s estate of Malguri, his stays with Uncle Tatiseigi when mani was in charge of himc not to mention his two years in space, with just mani and nand’ Brenc and his human companions, Gene, Artur, and Irene and all—those had been the good times, the very best times. Everything had gone absolutely his way for two wonderful years—

And then they’d come home to a mess in the capital, and in the Bujavid, and his parents had demanded to have him back and would not let him have access to nand’ Bren or Banichi anymore. His father being the aiji, his father got what he wanted, and got him back, just as simply as that, and put him under one and the other tutor and told everybody in his whole association except Jegari and Antaro to get entirely away from him and leave him solely with his parents.

Which was why nand’ Bren had to avoid talking to him, even if he lived almost next door.

And why mani had gone away to Tirnamardi with Uncle, leaving her own apartment and her comforts and her staff behind.

It was why there was absolutely no chance at all his father was going to send up to the ship-aijiin and request Gene and Artur to come down to visit him. The space shuttles were flying again, and Gene and Artur didn’t mass much, compared to all the loads of food and electronics they were flying up there to the station. But no. He didn’t even get messages from Gene and Artur, just one, when he wrote to tell them he was safe, and about all his adventures. Gene and Artur and Irene had each written him a letter admiring his adventures and asking questions, and he had written back, but there had been no answers since then; and he knew his letters were either never sent, or their answers had never gotten to him; and Gene and Artur and Irene would take his silence as hopeless, and give up tryingc forever.

He was a prisoner, was what. A prisoner. He’d tunneled out when his father’s enemies had tried to keep him. But there was no lock on his door in his father’s residence—just guards, just his tutor, just ten thousand eyes that were going to report it if he stepped sideways.

And then where would he go if he did get out? He could hardly get aboard the shuttle in secret, and they would only send him back when they caught him. If he went anywhere in the whole wide world, they would send him back to his father.

He treasured those three letters, as his most precious things in the whole world.

Soc with mani-ma in residencec maybe he would have no better luck with letters, though he would certainly tell her he suspected connivance against him! But one of two fairly good things could happen with mani: mani-ma could settle in to stay with them and perhaps coddle him a littlec or his father and mother could take a vacation at Taiben, and even if they took him away with them, he would have that. Neither was too bad.

So, foreseeing the need for a good appearance, he became a model of good behavior. He dressed, with Jegari’s help, in his finest, with lace at cuffs and collar. Jegari braided his queue and tied on the red-and-black ribbons of the aiji’s house, and he waited, pacing, until Jegari and his sister Antaro had gotten each other into their best—very little lace, since they were Taibeni, foresters, but very fine leather coats and immaculate brown twill for the rest: mani could not possibly find fault with them.

“I want to talk to mani before she goes into the dining room, nadiin-ji,” Cajeiri said. “We need to put her in a good mood toward us.”

“Yes,” Antaro said, and, “Yes,” Jegari said. So they left the room, not escaping the attendance of his assigned grown-up bodyguard—and headed down the hall toward the drawing room.

He saw Cenedi, silver-haired Cenedi, mani’s bodyguard and chief of staff, resplendent in his formal uniform, and immediately next to him he saw mani herself, small, erect, and absolutely impeccable, walking with her cane, tap, tap, tap, toward the dining room.

He lengthened his stride to intercept mani and Cenedi, and met them with a little bow, exactly proper.

“Mani-ma! Welcome! One is very glad!”

“Well, well.” The aiji-dowager—Ilisidi was her name—rested both hands on the formidable cane and looked him up and down, making him wonder if somehow his collar was askew or he had gotten a spot on his coat. His heart beat high. No. He was sure he had no fault. Mani looked at everybody that way, dissecting them as she went. “We see some improvement.”

Another bow. “One is gratified, mani-ma. One has studied ever so hard.”

And a reciprocal scrutiny. “My great-grandson is availing himself of my library.”

“Indeed, mani-ma. I am reading, especially the machimi.”

“Well, well, an improvement there, as well.”

“You will teach me now! You know so much more than the tutors!”

“Flattery, flattery.”

“Truth, mani!”

“Well, but we will not be at hand to tutor you, Great-grandson. We are here only for the night, then back to Malguri.”

His heart sank. Malguri was mani’s own district, clear across the continent, a mountain fortress. He had been there.

And it was an alternative—if he could go there. There were mecheiti to ride. Rocks to climb. “I could come there, mani. Take me with you! I learn far less with the tutor than with you andCenedi!”

Did she soften, ever so little? She hesitated a few heartbeats: he saw it in her eyes. Then: “Impossible. You are here to become acquainted with your father. You are here to learn the arts of governance.”

“But I have!” He lapsed into the children’s language, realized it, and amended himself, in proper Ragi. “Mani, one has improved entirely.” He saw his grand chances slipping away from him and snatched after something more reasonable. “A few weeks, mani. One would wish to visit you in Malguri for only a few weeks, and then go back to lessons. Surely you could persuade my father.”

“No,” mani said regretfully. “No, boy. We have had our time, in two years on the ship. Now you have to learn from your father.”

“Then stay here, please! This is a big apartment!”

“Not big enough,” Ilisidi said. “Not large enough for your father’s staff and mine, not large enough to keep us from arguments, and your father has enough to do in the upcoming legislature.”

“And he will be busy, and have no time for me!”

“Language, boy.”

“He will be busy, mani, and I shall be obliged to stay to my tutor. Even nand’ Bren has gone away to his estate. I shall have no supervision and you know I should have!”

“Your great-uncle will be here.”

That was the grimmest prospect of all, but he kept that behind his teeth and simply bowed acknowledgment of the fact. “But one will miss your society, mani. One could learn so muchc of manners, and protocols, and historyc”

“Well, well, but not at Malguri, I regret to say, where I must be, and you must be here, boy, you simply must. Come, let us go to dinner; and then we will say our good-byes tonight. Weather is moving in from the west, and we shall be leaving before dawn tomorrow, at an hour much before a young boy will find it convenient, quite certainly.”

“One will get up to say good-bye, all the same.”

“Oh, by no means,” Great-grandmother said, and tapped the cane on the floor, rap-tap, a punctuation to the conversation, as she started walking again, and so did Cenedi, and he was obliged to keep pace. “You will get your proper sleep and apply yourself profitably to your lessons. We shall be taking off before first light. We know, we know your situation. You must bear it.”

“Mani.” He was utterly downcast, but he had mani’s sympathy, and that was an asset never to waste. If he could not get one thing he wanted, he could try for another, and he had his choice: permission for a television in his room, which his father would probably forbid, or mani’s backing in the business of the letters to the space station—which was as important to him. “Mani, to my letters—which I wrote to the station—there has been no answer; and one almost suspects these letters are being held, which would be a reasonable consequence, mani, if one had not applied oneself to one’s studies, which one has done, very zealously! So if you could possibly, possibly ask my father about communications to the space station, and find out if Gene has even received my letter or if possibly—possibly there is some security question from the ship-aijiin, or maybe Gene has said something improper, or I have– It is so important, is it not, mani-ma, for me to understand these proprieties and maintain contact with my associates up above, and not to lose this advantage of association, when I am aiji? One cannot be offending these individuals. It would hardly be politic to offend them due to some foolish misperception!”

Tap went the cane, sharply. “Rascal.” She saw right through him. Clear as glass.

“Yes, mani. But—”

“Your argument is rational.”

A little hope. A little lessening of Great-grandmother’s frown. “One earnestly hopes to be rational, mani.”

“We shall think on it.”

“Yes, mani.” It was not the agreement he hoped for. He got pleasantness: he got warmth: but he did not get yes.

Still, with Great-grandmother, one did not sulk. One definitely did not sulk, nor allow an expression of discontent. Never let an opponent see into your thoughts, mani would say. And: Whatis that expression, boy?

Mani was more than hard to argue with. “Think on it” was as much as he was going to get if he kept after her for reasons, and mani would not be persuaded to stay. He would have Great-uncle down the hall, arguing with his father and trying to instruct the guards Great-uncle had set over him, and, worse, asking them when he breathed in and when he breathed out. He was not happy with the evening thus far.