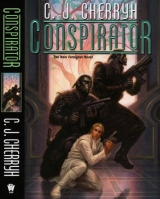

Текст книги "Conspirator"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

There was an advantage, however, to nobody caring what he thought, and to his aunt’s maids acting like fools, which was that people grew busy and forgot to pay attention to him. He had not gotten in trouble in at least half a month, which meant that he was not under active restriction at the moment.

So he went down the hall and searched up boring old Kaidin and Temein. They were finishing the day’s reports when he found them; and he said:

“Nand’ Bren has a book I need for my studies.”

A sour look. “We can get it, young lord.”

He thought fast. “This is a very old book, and I have to convince nand’ Bren I can take care of it. No farther than just down the hall. I need to talk to him. I can go by myself or you can take me there.”

“We should ask the aiji’s staff,” Temein said. He was not the most enterprising of men; and Kaiden thought they should clear the order, too—to Cajeiri’s disgust.

“My father’s staff by no means cares if I am only in the hall,” he said. “Or if you go with me at all or not. But one needs to go now, nadiin. I have to meet my tutor before lunch. If you go to asking questions and going through procedures, I shall not get the book read in time, I shall not finish my lessons, my tutor will give a bad report, my father will be upset with me, and I shall be put out with you. Extremely. Come with me. We need to go now. It will hardly take a moment.”

They muttered to each other. They had only just ordered lunch, were not anxious to leave for a long consultation and getting permission, so the ploy actually worked. He got them out the door, and three doors down, and had them knock on nand’ Bren’s door—or Uncle Tatiseigi’s.

“We need to talk to nand’ Bren,” Cajeiri said to the maid who answered it, and when Madam Saidin showed up: “Nand’ Bren has a book I very much need, Saidin-nadi. May I speak to him?”

“Yes, young gentleman. Come this way,” Madam Saidin said, and, leaving Kaidin and Temein in the foyer, she escorted him to the study, where she knocked softly, and opened the door.

Nand’ Bren was writing. He looked up in a little surprise, and stood up to meet him, even if nand’ Bren was Lord of the Heavensc stood up to just his height, being a human, and just his size, which always made nand’ Bren seem more like his own age. Lord Bren was all the colors of a sunny day—pale skin and pale hair and eyes and all. When Cajeiri had been very little, he had wondered if Bren was the only one in all the world like that. When he was older, he had found out Bren’s kind came in all sorts of shades; but, even so, very few were Bren’s sortc and fewer still of any species were as smart as Lord Bren. Lord Bren was his father’s trusted advisor, and when Lord Bren talked, his father the aiji listened.

Well, mostly, his father did.

“Nandi,” he said to Lord Bren, ever so respectfully—and quietly, aware Temein and Kaidin were just outside, and probably talking and reporting to Saidin, because they wereactually all from Great-uncle’s estate of Tirnamardi. “Please lend me one of Uncle’s books. I told Saidin-nadi that I came for one. Are you really going away?”

“Yes,” nand’ Bren said. “Only for a month, until the legislature meets.”

“You mean to go to the coast. Where your boat is.”

“Yes,” nand’ Bren said, just a bit more warily. “Just for a while.”

Guilt was useful; and Cajeiri had no hesitation to use it. “You promised when you did ever go on your boat you would take us along.”

Nand’ Bren looked decidedly uncomfortable. “Not without your father’s permission, young lord, one could not possibly—”

“Then one hopes you will ask him, nandi. One ever so wants to go!”

“I shall ask him,” nand’ Bren said quietly, as if it were an obligation, a very wearying obligation.

That stung. And that made Cajeiri angry.

“Young lord,” nand’ Bren said, “he will surely say no. But one will make the request.”

Nand’ Bren still looked tired, and entirely out of sorts. Perhaps it was not himself that nand’ Bren was out of sorts with.

“You did promise,” Cajeiri said, pushing it, in that thought, “and one is so boredwith lessons.”

“One did promise,” Bren agreed with a sigh. “And one regrets to have so little hope of persuading your father, but one fears he will refuse any request. If you recall, young lord, you are intended to become reacquainted with your father and your lady mother, and to learn the court and the legislature—for your own protection and future benefit.”

“Great-uncle is entirely unreasonable to send you away!”

“Lord Tatiseigi has been very generous to have lent this apartment at all,” Bren said, “and when he comes to the capital, he naturally needs it. Should he take a room in the hotel?”

“But where are you to go when the legislature is in session? Shall you not be here?”

“ ‘Where are you to go,– nandi?’” Nand’ Bren corrected his mode of address, since his voice had risen far too sharply and he had just omitted a courtesy to moderate that sharpness.

“Nandi,” he amended his question, ducked his head and made his voice and his manner far more quiet and restrained. “But where are you expected to go?”

Nand’ Bren smiled sadly, patiently. “Clearly, for the immediate future, to the home I do have, which I am very grateful to have. After that, young lord, perhaps I shall take a town house.”

“If wecould, we would assuredly toss the Farai out of your apartment!”

“One is very sure your father daily entertains the same thought, young lord.”

“Then he should do it! He should File on them!”

“One is very sure he would do it, if not for the fragility of the peace, young lord, but in the meantime, my brother happens to be sailing near my estate—I spoke to him a few days ago when he was in port on Mospheira. So my trip to the coast is not all a loss. I shall very probably get to see my brother. I also owe extravagant thanks to my staff in that district, who held out against the rebels, at the risk of their lives. And I owe a debt to Lord Geigi—up on the station: you remember Lord Geigi. His estate is next down the coast.”

“One remembers Lord Geigi favorably, yes,” he said. Nand’ Bren was clearly explaining to him that there were all sorts of social obligations already lined up for him, with no time for taking a boy on his boat, that was what, and he hardly liked to hear the whole list. “One remembers nand’ Toby, too. And Barb-daja. Theywould certainly find pleasure in seeing us, and hearing all our adventures.”

“Surely they would,” Bren said, not unkindly. “And surely the estate staff would be greatly honored by your presence, and so would Lord Geigi’s people be glad to receive you, but your father—”

“The paidhi-aiji persuaded all the districts to make peace when they were at each other’s throats! Surely you can persuade my parents to let me go to the coast for a month!”

Nand’ Bren smiled and shook his head in the human way, and said: “I shall honestly try, young lord. I shall certainly do that.” He went and took a book from the shelves, taking a little trouble about it. It was, of course, Great-uncle Tatiseigi’s book that nand’ Bren lent him.

It was a very handsome little book, very old. Cajeiri appreciated the trouble taken, at least, and folded it to his chest. He bowed respectfully, and nand’ Bren bowed.

But when Cajeiri walked out of nand’ Bren’s office he found himself madder and more frustrated than he had been in a long, long time. He did not even look at Kaidin and Temein on the walk back, nor did he say a word.

When he got safely back to his own room, in his father’s borrowed apartment, and was rid of his guard, he flung himself into a chair and flung the book onto the table beside him. It nearly slid off the table. He stopped it.

Then he thought to look at the book. It was the sort of thing his great-uncle would have, the script of a machimi play. But it was one he had never seen or read. It was titled Blood of Traitors. The illustration chased into the leather cover, and painted, had swords and castles. And nand’ Bren had picked it out, which meant it might be very much better than the volume of court rules and etiquette his tutor was making him memorize.

It was no substitute for sailing on nand’ Bren’s boat, and none for seeing nand’ Toby and Barb-daja.

He had caught a fish on nand’ Toby’s boat once. It had been venomous, and it had flown all about on his line, making everybody scramble. It was one of his most favorite memories. They had all laughed about it later, himself, and Great-grandmother, mani; and nand’ Bren and his associates, even when things were desperate and people had been trying to kill them—even the fish in the sea had had a try at killing them. And that had been the best moment on the whole boat trip.

He so wished he had never told his parents about it.

Chapter 2

« ^ »

A very good idea,” was Tabini’s judgment to Bren regarding his removal to the coast, by no means surprising. A young man, still, a big wide-shouldered man, with the palest stare Bren had ever seen in an ateva—Tabini had ruled the mainland all the years he had served as paidhi. Tabini ruled the atevi world, in effect, though a recent challenge to his authority had racketed from east to west, provoking counter-revolution and skirmishes after.

But Tabini had resurrected himself from rumored death the moment Tabini had been sure he had his assets back in order– notably, when the paidhi and the aiji-dowager and his heir had come back from space alive. Tabini had come back, from what had been a cleverly planned assassination designed to take out first his staff (which had happened) and then isolate and kill Tabini himself (which plainly had not happened.)

In fact, within a few weeks of Tabini’s re-emergence from the hills, the capital showed few scars, most of the conspirators were dead, the always troublesome South, the Marid, was quiet, certain few had paid heavily for backing the Kadagidi Lord Murini in his coup, and Tabini had become again what he had always been: ruler of the world’s only major continent, owner of half the human-built space station in orbit above them, owner of every functional space shuttle in existence, linking the world to that station; and incidentally owner of a half-built starship, which had been the agreement the ship-humans had made with Tabini in order to get their vitally needed supplies off the planet.

Tabini’s space program had put a strain on the economy: that had been the origin of the Troubles, at least in some sense—but the panic and outrage that had attended the departure of the one viable ship and all that investment had abated with the return of said ship from its mission. On new evidence that the ship-humans were actually going to keep their word and honor their agreements, Tabini’s stock had risen indeed. Humans on the island enclave of Mospheira had not invaded the mainland: they had in fact cooperated with the ship-humans and with Tabini, and that old fear had proved empty.

It was, in some senses, a new world. Tabini had taken a renewed tight grip on the reins of power, and if there still were minor nuisances, like the Farai still occupying the paidhi’s apartment and pretending to be loyalists, it was also true that Tabini was a master of timing. If it was not yet time to pitch the Farai out and stir up the Southern troubles again, the paidhi could only conclude it was definitively not yet time, and the paidhi’s best interim course was probably to go visit his brother.

“We shall hope for some solution before the legislative session,” Tabini said.

“One thinks of taking a town house, aiji-ma,” Bren said, “but staff will deal with that process.”

Some legislators did that, at least for the session. Certain town families rented out their premises for the season at a profit. Housing was at that kind of premium in the town. But even if they went to that extreme—it was no permanent solution.

“Give it time, paidhi-ji,” Tabini said again, not favoring his proposed solution with a direct answerc neither saying the Farai would be out of his apartment in a few weeks, nor saying they wouldn’t be.

So a wise and experienced court official simply nodded, thanked the aiji for permission to depart the city and didn’t ask another question, even as easy and informal as Tabini had always been with the paidhi-aiji.

But he had promised—once, to take the boy; and a second time, to ask a foredoomed question. “Your son,” he began, and got no further before Tabini lifted the fingers of one hand. Stop right there, that meant.

“My son,” Tabini said, “just visited your premises.”

“He did, aiji-ma. He reminded me I did promise him a boat trip.”

“Not recently, surely.”

“No, aiji-ma. But your son has an excellent memory.”

Tabini sighed. “Indeed. He has lessons. He has duties. He was not to have left the premises. And he asked you to use your good offices with me. Am I right?”

“Entirely, aiji-ma.”

“Perhaps we can prevail on the workmen in ourapartment to make a little more haste,” Tabini said, “and solve one problem—but not before my grandmother arrives. No, my son may notgo to the coast, paidhi-ji. He will stay here to keep his great-grandmother in good humor. Now you have discharged your obligation to him. And Irelieve you of responsibility for the promise. My son will have to deal with me on that matter. Go, go. We have ordered the red car for your trip; it should be coupled on by now. The paidhi-aiji will have it at his disposal on the return as well, on a day’s call. Tell nand’ Toby we wish him well.”

“Thank you, aiji-ma,” he said, and rose, and bowed deeply. The red car, no less. The aiji’s own rail car, with all its amenities, and its security. It was no small honor, though one he had almost always enjoyed.

At no time had he mentioned Cajeiri coming to his office, and at no time had he mentioned Toby being near the estate, or intending a visit: but he was not totally astonished that Tabini knew both things.

He simply went to the door, collected Banichi and Jago, and Banichi said,

“The estate has contacted nand’ Toby, nandi, and he will be arriving.”

“Did he say whether Barb was with him?” he asked. He hatedto ask. One could always hope she wouldn’t be. But Banichi simply lifted a shoulder and said.

“We have never heard she has left.”

“Well,” he said, which was all there was to say.

Packing had proceeded, even when they had had no permission as yet to quit the city. Tatiseigi being a day short of their doorway, the baggage had been stacked in the hall, the dining room, and the foyer, involving security equipment, armament, ammunition, uniforms for his four bodyguards, and a few meager items of furniture, plus four packing crates with his clothes, his books, and his personal itemsc all this had been the state of things when he had left the apartment to call on Tabini.

Tano and Algini estimated seven rolling carts and some of Tatiseigi’s staff to get their baggage down to the train.

“Are we ready to load up, then?” he asked. “The aiji said we should use the red car. That it was being coupled on right now.”

That car waited, always ready, always under guard, in the train station below the Bujavid itself; and taking it on took very little time. The train that loaded at the Bujavid station backed up onto that reserved section of track, connected with it and its secure baggage car, and that was that.

“It should be on by the time we get down there,” Banichi said, evidently as well-informed from his end of things as the aiji was on the other. “The carts are on their way up. Tano and Algini will see to that.”

Things might have gone either way. If Tabini had said no, they would have been on their way to the hotel and most of his goods on their way to storage. As it was, they were on their way to the train station in the Bujavid’s basement.

“I should say good-bye to Saidin,” he said, and went the few doors to the apartment down the hall to do that personally– knocking at the door that had lately been his, but he no longer felt it was. Madam Saidin answered, perhaps forewarned, via the links the Guild had, and he bowed. She bowed, letting them in, and Banichi and Jago picked up the massive bags they had destined to go with them.

“One is lastingly grateful for the hospitality of this house,” he said, and picked up the computer he had left in the foyer; that, and a large briefcase. “One is ever so grateful for your personal kindness, Saidin-nadi, which exceeds all ordinary bounds.”

“One has been honored by the paidhi’s residence here,” she said, with a little second bow, and that was that. He truly felt a little sad once that door shut and he walked away with Banichi and Jago. He would miss the staff. He had staff of his own to look forward to, but he had been resident with these people more than once, and perhaps circumstances would never combine to lodge him in this particular apartment againc Tatiseigi’s political ambitions had lately become acute, and his age made them urgent. Possibly those same ambitions had made him lend the apartment last year, to solve a problem for Tabini, but with the legislative session coming up, and with Tatiseigi’s long-desired familial connection to the aijinate now a reality– in Cajeiri—Tatiseigi now had a motive to bestir himself and actually occupy the seat in the house of lords that he had always been entitled to occupy. The world likely would hear from Tatiseigi this legislative session, and hear from him oftenc not always pleasantly so, one feared. One could see it all coming– and one sohoped it observed some sense of restraint.

Jago added the briefcase to her own heavy load as they boarded the lift. The briefcase held several reams of paper notes, correspondence, a little formal stationery and a tightly-capped inkpot, wax, his seal, and his personal message cylinder. He still carried the computer.

And there was one other obligatory stop downstairs, an advisement of his departure and a temporary farewell to his secretarial office, another set of bows and compliments.

And another set of papers which his apologetic office manager said needed his urgent attention.

“I shall see to them,” he assured that worthy man. Daisibi was his name—actually one of Tano’s remote relatives. “And have no hesitation about phoning me. I shall be conducting business in my office on the estate at least once a day, and the staff there is entirely my own. Trust them with any message, and never hesitate if you have a question. I shall be back five days before the session. Rely on it.”

“Have an excellent and restful trip, nandi,” Daisibi said, “and fortune attend throughout.”

“Baji-naji,” he said cheerfully—that was to say, fate and fortune, the fixed and the random things of the universe. And so saying, and back in the hallway headed back to the lift, he felt suddenly a sense of freedom from the Bujavid, even before leaving its halls.

He had a hundred and more staff seeing to things in this officec he had them sifting the real crises from the odder elements of his correspondence.

And more to the point, he could notbe hailed into minor court crises quite as readily from this moment on.

The Farai were no longer, at the moment, his problem. Uncle Tatiseigi was not.

And as much as he adored the aiji-dowager, Ilisidi, crisis would inevitably follow when she was living with an Atageini lord a few doors down from her own apartment—which was now and until Tabini’s move to his own apartment—under the management of her grandson Tabini’s staff.

Things within the apartment would not be to Ilisidi’s liking. They were bound not to be. The management of her grandson would become a daily crisis.

Uncle Tatiseigi would voice his own opinions on the boy’s upbringing.

And hewould be on his boat with his brother, fishingc for at least a few hours a day.

He almostfelt guilty for the thought.

He almostfelt grateful to the Farai, considering the incoming storm he was about to miss.

Not quite guilty, or grateful, on either account.

The train moved out, slowly and powerfully, and the click of the wheels achieved that modest tempo the train observed while it rolled within the curving tunnels of the Bujavid.

Bren had a drink of more than fruit juice as he settled back against the red velvet seats, beside the velvet-draped window that provided nothing but armor plate to the observation of the outside world: Banichi and Jago still contented themselves with juice, but at least sat down and eased back. Tano and Algini had taken up a comfortable post in the baggage car that accompanied the aiji’s personal coach. Bren had offered them the chance to ride with them in greater comfort, but, no, the two insisted on taking that post, despite the recent peace.

“This is no time to let down one’s guard, nandi,” was Tano’s word on the subject, so that was that.

So they made small talk, he and Banichi and Jago, on the prospect for a quiet trip, on the prospect for Lord Tatiseigi’s participation in a full legislative session for the first time in twenty-one felicitous yearsc and on the offerings they found in the traveling cold-box, which were very fine, indeed. Those came from the aiji’s own cook, with the aiji’s seal on them, so they could know they were safe—as if the aiji’s own guards hadn’t been watching the car until they took possession of it. Even his bodyguard could relax for a few hours.

It was all much more tranquil than other departures in this car. The coast wasn’t that far, as train rides went, and the aiji had done them one other kindness—he had lent an engine as well, so the red car was not attached to, say, outbound freight. It was a Special, and their very small train would go directly through the intervening stations with very little pause. They might even make Najida by sundown, and they could contemplate their own staff preparing fine beds under a roof he actually owned for the first time since they had come back from space.

A little snack, a little napc Bren let himself go to the click-clack of the wheels and the luxury of safety, and dreamtc

Dreamt of a steel world and dropping through space-time.

Dreamt of tea and cakes with a massive alien. Cajeiri was in this particular dream, as he had been in actual fact. Prakuyo an Tep loomed quite vivid in Bren’s mind, so much so that, in this dream, the language flowed with much less hesitancy than it did in his weekly study of it. He dreamed so vividly that he found himself engaged in a philosophical conversation with that huge gentleman, with Cajeiri, with the aiji-dowager, and with peace and war hanging in the balance.

He promised Prakuyo an Tep that indeed this was the son and grandmother of the great ruler of the atevi planet (a mild exaggeration) and a partner with humans (true, mostly) in their dealings with the cosmos. He had done that, in fact.

Humans having greatly offended the kyo, he had collected the whole stationful of them that had so offended, and delivered them back to the star they shared with atevi.

Humans having so greatly offended the kyo, he had persuaded the kyo that atevi were a very great authority who would make firm policy and guarantee humans’ good behavior in future.

Most of all, he had shown the kyo, who had never seen another intelligent species prior to their exiting their own solar system, and who had somehow gotten into space with noconcept or history of negotiation—one shuddered to think how– that two powerful species could get along with each other andwith the kyo—a thunderbolt of a concept the paidhi had no illusions would meet universal acceptance among the kyo.

Prakuyo an Tep, over a massive plate of teacakes, miraculously and suddenly resupplied in this dream, vowed to come to the atevi world and document this miracle for his people, a visit which would persuade them to conclude agreements with this powerful atevi ruler and his grandmother and son—agreements which would of course bind all humans—and together they would find a way to deal with the troublesome neighbors on the kyo’s otherperimeter: God knew whether that species had a concept of negotiation, either.

But the paidhi, the official translator, whose job entailed maintenance of the human-atevi interface, and the regulation of mandated human gifts of technology tothe atevi—according to the treaty which had ended the War of the Landing—had apparently another use in the universe. He was supposed to teach the kyo themselves the techniques of negotiation.

And simultaneously, back on the planet, he had to make sure Tabini’s regime was secure and peaceful.

And make sure Tabini’s grandmother was in good humor.

And make sure Tabini’s son didn’t kill himself in some juvenile venture, anddidn’t take so enthusiastically to things human that he ended up creating disaster for his own people on the day he did take over leadership of the aishidi’tat.

He really had hated to say no to the boy, who had harder things to do than most boys. He hadpromised him a boat trip.

And he sat there having tea with the kyo and telling himself he was firmly in charge of all these things. He had lied a lot, lately. He really didn’t like being in that position, lying to the boy, lying to the kyo, lying to—

Just about everybody he dealt with, exceptBanichi and Jago, and Tano and Algini. They knew him. They forgave him. They helped him remember what he had told everybody.

And pretty soon now, he was going to have to lie to the atevi legislature and tell them everything was under controlc when they all knew that there were still plenty of people out there who thought the paidhi hadn’tdone a great job of keeping human technology from disrupting their culture.

This didn’t, however, stop atevi from being hell-bent on having wireless phones. Some clans thought his opposing their introduction was a human plot to keep the lordly houses at a disadvantage—because the paidhi’s guard had them, and probably Tabini’s had them, and nobody else currently could have them. Clearly it was a plot, and Tabini was in the pocket of the humans, who secretly told Tabini what to doc they became quite hot about it.

Tea with Prakuyo became the windblown outside of a racing locomotive, with a great Ragi banner atop, and the paidhi sat atop that engine, chilled to the bone by an autumn wind, hoping nobody found his pale skin a particular target.

They were coming into the capital. And the people of Shejidan might or might not be glad to see Tabini return to powerc

“Bren-ji.” Jago’s voice. “We have just passed Parodai.”

They were approaching the lowlands. In the red car. Carrying all his baggage.

He was appalled, and looked at Banichi and Jago, who had gotten less sleep last night than he had, and who were still wide awake.

Maybe they had napped, alternately. Maybe Tano and Algini were taking the opportunity, safely sealed in the baggage car. He certainly hoped they were.

Had he been wound that tight, that the moment he quitted the capital, he slept the whole day away? He still felt as if he could sleep straight through to the next morning.

But he had now, with Banichi’s and Jago’s help, to put on his best coat, do up his queue in its best style, and look like the returning lord of his little district.

He owed that, and more, to the people of the district, who had held out against the rebels.

He owed it to the enterprising staff, many of them from the Bujavid—who had fled during the coup and simultaneously spirited away his belongings—which had consequently notfallen into the hands of the Farai.

His people had held out on his estate, staying loyal to him when that loyalty could have ultimately cost them their lives.

That it had not come under actual attack had been largely thanks to the close presence of Geigi’s neighboring estate and the reluctance of anyoutsider to rouse the Edi people of that district from their long quietc the Edi, long involved in a sea-based guerilla war with almost everybody, were at peace, and not even the Marid had found it profitable to add the Edi to their list of problems. The west coast was remote from the center of the conflict, which had centered around the capital and the Padi Valley—and it just hadn’t been worth it to the rebels to go after that little center of resistencec yet.

He’d gotten home in time. Tabini had launched his counter-coup in time. The estate had held out long enough. The threat of war was gone and Najida stood untouched.

And the paidhi-aiji owed them and Geigi’s people so very much.

He had fresh, starched lace at collar and cuffs, had a never-used ribbon for his queue—the ribbon was the simple satin white of the paidhi-aiji, not the spangled black of the Lord of the Heavens, which he very rarely used. He sat down again carefully, so as not to rumple his beige-and-blue brocade coat, and let Banichi and Jago put on their own formal uniforms, Guild black, still, but with silver detail that flashed here and there. Their queues were immaculately done, their sleek black hair impeccable—Bren’s own tended to escape here and there, blond wisps that defied confinement.

He opened up his computer for the remainder of the journey. He’d hoped to work on the way, on matters for the next session. He’d slept, instead, and now there was time only for a few more notes on the skeleton of an argument he hoped to carry into various committees. Atevi, accustomed to the various Guilds exchanging short-range communications, had seen the advanced distance-spanning communications they had brought back from the ship, and gotten the notion what could be had.

Worse, humans on Mospheira had adopted the devices wholesale and set up cell towers, and the continent, thanks to improved communications, knew it.

He had to argue that it wasn’t a good idea. He had to persuade an already suspicious legislature, reeling from two successive and bloody purges—one very bloody one when Tabini went into exile, and one somewhat less so when he returned—that he was notarguing against their best interests, and that after all the unwelcome human technology he had let land on the continent, he was going to say no to one they wanted. And the paidhi’s veto, by treaty law, was supposed to be absolute in that arena. That, too, was under pressure: if he attempted to veto, and if Tabini didn’t back him and the legislature went ahead anyway, that override weakened the vital treaty—and did nothing good for the world, either.