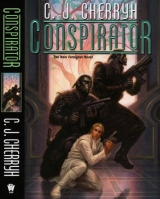

Текст книги "Conspirator"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“Tell your honored grandmother, tell all the council, Osi-nadi, that Najida will not accept Kajiminda falling into the hands of the Marid; it will not accept Marid presence on this coast. The lord of Najida estate wishes to meet with the council, in the council’s premises, and asks to be invited to speak, at a time not to interfere with their session.”

“Nandi!” A deep bow from the dusty young man. “Certainly they will be honored.”

“Nevertheless,” Bren said, “Osi-nadi, make the request for me. One wishes to listen to advice as much as to give it. One requests, Osi-nadi. And advice. Please say that, exactly.”

“Nandi.” Another bow.

“Go, Osi-ji,” Ramaso said. “The lord’s commission outweighs mine.”

“I have my measurements,” the young man said, tapping his head, and made a third bow. “Ramaso-nadi. Bren-nandi. I shall, one shall, as fast as I can.”

The young man was off like a shot, back toward the main doors, not the nearest, which were probably still secured. His footsteps echoed on the retreat.

“It is a great risk to go down to the village, nandi,” Ramaso said, “a risk for you to leave these premises.”

“Not from them.”

“No, nandi! Of course not!”

Honest distress. They let him run into danger. They didn’t know how to stop him without unraveling everything. He began to see that. No danger fromthe village. But the village couldn’t feel safe. Nobody could, as things stood.

“My guard will keep me safe, I have no doubt. My worry is my attracting attack into the village, Rama-ji, and I know what I ask. Guide me in this. If one asks protection from the aiji in Shejidan, it will be counter to all I hope to achieve. One does not wish to see Najida village dragged into politics with the South.”

“With the South, nandi?”

“The Marid will seek to divide Maschi from Edi, Edi from Korali—wherever they can find a weakness. One believes– one sincerely believes, Rama-ji, that in the aishidi’tat is the best association for all the Western clans. But this needs to be proved—to the Western clans. And it cannot be proved by bringing central clan Guild in here to settle things by force. It was never the power of the aiji in Shejidan that protected this coast. It was the people.”

Ramaso himself was Korali. And Ramaso nodded solemnly and slowly. “The absence of both the paidhi-aiji and the Lord Geigi has been a weakness on this coast. Our isolation from politics protected us. But Najida welcomesyour return, nandi. I am, at least by birth, an outsider, though my wife is from Najida. But I believe the village will heartily welcome your close involvement.”

“One regrets extremely the necessity of my service in space. Najida has deserved better.”

“Najida could not find better than you, nandi. That is your staff’s sentiment. You are—if the paidhi will forgive a political opinion—outside the regional rivalries. You are not Edi. But you are not Ragi. There was a reason your Bujavid staff fled here; there was a reason Najida welcomed them and hoped for your return; there was a reason the Marid found it inconvenient to attempt to take this coast, and the reason was exactly as you say. The resistance in Dalaigi relied on this house to reach Dur; and so we did; and Dur reached the Island, and from Dur we acquired direction and advice at need; and we gave each other assurances that there wouldbe a rising against the new regime. We were not idle in your absence, nandi, even though we counted on no help from Kajiminda—and less from the center of the continent. One must ask the paidhi’s forgiveness—his great forgiveness—for notwarning the paidhi about the situation with Kajiminda, which we did notknow. We did not know Guild had come from the South. We were unwarned.”

“The grass was not mown on the road, Rama-ji. There were so many signs. One laid them all to a decline in trade.”

Ramaso bowed his head, shaking it slowly. “We thought it irresponsibility. We thought it—perhaps—that the house couldnot pay its debts. We thought perhaps the presence of the Lord of the Heavens would bring Lord Geigi’s nephew to a better frame of mind. One feels personally at fault, nandi. Should you wish it—one is prepared to be dismissed from this post of responsibility.”

“Do not consider it. The aiji’s own information failed.”

Ramaso’s face showed rare emotion, a soul greatly disturbed. “This I can say, nandi. I have been in touch with—with the activities of the village council, in matters here and—those things I spoke of—the contacts with the North. And if my knowledge will serve you, nandi, I shall answer to you. Not to the aiji, nor even the paidhi’s distinguished guests. I answer to you.”

He was stunned. He had corresponded with Ramaso before and after his return. He had exchanged observations with Ramaso, and trusted this man, in happier days, to bear with his family, at a close range that would have worried him—were it not level-headed Ramaso. He had not had the least inkling what this man had been, or done, during the Troubles.

“Rama-ji. What can one say?”

The impassive mask resumed, and, with a little quirk of the lips: “Say little, to the aiji, nandi. And little to any of your staff who might report to him. But our records—will be open to you.”

His bodyguard. Who were extremely closely tied to the aiji’s house.

And it wasNajidama Bay he was dealing with, which had had a local tradition of smuggling, and even of wrecking; and there had historically been business enterprises Najida village might not want to have told to the aiji, and there was a time a light up by the Sisters had lured the aiji’s shipping to ruin—

Butc not to tell his bodyguardc

“One even asks, nandi, didthe aiji send his son here, so conveniently?”

“No, Rama-ji. On that point, one is relatively certain, there was no planning in that.”

“No desire, nandi, forgive me, for an excuseto send Guild to the coast?”

“No, Rama-ji. The young gentleman is entirely what he seems. Fluent—in Mosphei’, at least as the ship-folk speak it. He is many things, but not—not orthodox Ragi, nor ever will be. He has associates among human folk. He has a great attachment to the aiji-dowager.”

“One detected that attachment,” Ramaso said, and nodded slowly. “One has readily detected that.” And then Ramaso added: “This coast, up and down, has always respected the grandmothers.”

The same little chill ran through that statement, a chill of antiquity, ancient belief, ancient connections. The people of the coast had owned Mospheira once—the Edi, and the Gan, up in the Northern Isles, were the aboriginal peoples of the island.

The treaty that separated humans onto the island enclave, and atevi to the mainland, where the Ragi ruledc had made those two peoples homeless, refugees on this coast. It had been expedient. It had saved thousands of lives—assured the survival of the human species on the planet.

But it had left the former Mospheirans separated from their sacred sites. Their monuments had gone to museums. Their traditions had been swallowed up.

There had been two particular reasons that Tabini-aiji had appointed the paidhi as lord of Najida, when the clan that had had it went extinct. One reason: that a Marid clan, the Farai, had claimed to succeed the Maladesi, and Tabini didn’t want a Marid clan to get its fingers on Najida—and the otherc

The other reason had been that no central lord could have been accepted on this coast, no more than this coast would accept anyone from the Marid.

“Ramaso-nadi,” he said, “I will notdiscuss inappropriate things with the aiji; you have my word on that. My aishid may be Ragi—but they are in my man’chi, Rama-ji, and as they will not betray me, I will not betray them. I find myself connected here. I had no notion of the indebtedness I would come to feel toward this place. I am far more foreign. I do not feel in the same way, but I feel deeply. I shall become, at whatever time I speak for you, partisan forthis regionc and I shall keep its secrets, whatever of them I learn. And so, if you will forgive me, will that young man under this roof. He is not one who forgets a kindness. And he learns. Enlist him by means of your good qualities; enlist the aiji-dowager, who remembers favors done her great-grandson. These are not inconsequential allies, Ramaso. Tell thatto the village, if you will speak for me. I shall always be a foreigner. But not so much so here, one hopes. One earnestly hopes so.”

“You are alsoan exile from Mospheira, nandi. In that sense, you are one of us.”

True—if not in the same bitter sense as the Old Ones.

“Nadi-ji,” he said to Ramaso, with a little bow. Ramaso bowed. And he walked away, disturbed to the core.

Homeless on this earth. Except—here. Except one warm spot that—of all cold things it could possibly do to him—questioned Banichi’s man’chi, of all people.

Hedidn’t question it. True that Banichi still reported to Tabini, and came and went more easily with Tabini-aiji than some of Tabini’s own new bodyguard. But it never meant that Banichi or Jago would betray him.

It occurred to him to ask himself—if he took a stance for the people of the coast—did he, in fact, betray Banichi’sman’chi, in a way that would put Banichi in an untenable position?

He didn’t feel that. He had no such intention. If he found a limit he could not cross in that regard—he thought—he would stop at it. Banichi would never betray him, he would never betray Banichi, nor Jago, nor Tano, nor Algini.

He was what he was. Maybe Tabini had understood enough about him when he’d given him Najida, and maybe Tabini hadn’t.

He hoped Tabini had.

But he couldn’t turn his back on these people. Couldn’t go back to Shejidan, in the legislature, and sell out these people’s lands, or be in Tabini’s inner councils, and have the consideration of peace or war come down to the edge, and sell out these people’s interests. Last week—he might not have felt it that personally.

Since dodging bullets under his neighbor’s portico, it had become just a little—

The front door opened, making the dowager’s guards, who were stationed there, react. But it was just one of the youngest staff, out of breath and windblown.

Whose eyes darted to the leveled guns in alarm, and then went to him, large and desperate.

“Nandi! Nand’ Toby is coming in!”

“Sailing into dock?”

A bow, and the young man caught his breath, hands on knees. “Forgive me, nandi. Yes. Sailing in. The boat—nand’ Toby’s boat—is damaged, low in the water, and pumping hardc”

Damn, he thought, in a cold chill. “Come,” he said, and led the way into the study.

There he sat down while the servant waited, and wrote a quick note.

“ Toby– I’m delighted you’re all right but concerned you’re back here, which is not safe. We came under attack last night, we lost two on the dowager’s staff and have one man shot. We got what we went in after, all of them, and I hope you and Barb are both all right and will forgive me for not coming down there. My staff is getting medical treatment and we’re shorthanded. The way up and down the hill is exposed and snipers are a possibility, so be extremely quick and careful if you decide to make the run up here. Leave the baggage. You may be safer just to stay on the boat offshore. If you do come up here, you will have the safety of the house, but we’re in fortress mode at the moment and we can’t say this will be the last shooting that goes on. Staff will give you every possible assistance and get you up here if you choose to come. Stay well.

“ Love to you,

“ Bren.”

He folded the note, didn’t even use the wax seal, just handed it to the boy.

“Forgive my asking this of you, nadi, but go back down; and if there should be gunfire, fall down, get under the bushes and stay there. Someone will come to rescue you. The letter inquires into nand’ Toby’s situation and says he is welcome under this roof, but the situation up here is still hazardous and I personally cannot come down to the dock. He may be safer to remain in the harbor, possibly offshore. There may still be snipers. If he chooses to come up here, he will have the safety of the house. Advise persons guarding the dock exactly what I have said, and wait for a written reply from nand’ Toby if he chooses.”

“Yes, nandi!”

“Samandi is your name, is it not?”

“Yes, nandi!” A second bow, a bright, so-innocent look. “Thank you, nandi.”

“Please. Please be careful.”

“Yes, nandi.”

The boy was off like a shot.

And twice damn!

No calling the law in the district. He wasthe law in the district.

The two that attacked had been high-level Guild, no question, and on the highest levels, the Guild all knew one another. Algini in particular, who had served the last Guildmaster, likely knew their affiliations, and probably there was a host of other questions about the attack that his bodyguard would be discussing in detail. It was a discussion in which no non-Guild was welcome, not even the aiji.

Meanwhile his brother might be on his way up, most likely, with Barb; and God knew what “damage” meant. Or how incurred. Toby was a good sailor. A very good sailor.

He went out to the hall, down into the dining room, and went to the kitchens himself, or nearly soc he had reached midway in the serving hall before he met a servant, and he had only reached midway to the turn to the kitchen before the cook came hurrying out.

“Nandi! We are nearly ready to serve. One has your message, your staff and the dowager’s men—”

“There is more, Suba-ji. My brother and his lady have just put into dock. He may or may not come up to the house—be warned that there could be two more. At very least we shall need to send supper down to them.”

A bow. Suba carried a towel, and wiped his floury hands with that, looking somewhat satisfied. “Nandi, we have cooked enough for a seige. Every dish can be reheated, saved, served, or added to—nothing grand, but nothing to disgrace the house.”

“Every credit to the house, in your forethought, Suba-ji. One should never have been concerned. Excellent.”

“We shall be serving momentarily. We have rung the bells.”

Up and down the servants’ halls, that was: staff was advised of breakfast in the offing.

“Thank you. Thank you, Suba-ji,” he said, and walked out into the dining room, down the hall. He got no further than the intersection when the dowager emerged from her quarters with a grim-faced Cenedi in attendance, and the young gentleman and his two attendantsc the dowager disconcertingly resplendent in morning-dress, and from some source—possibly clothes the dowager had picked up in Shejidan when she refueled—the heir was himself kitted out in an impeccable blue coat. The paidhi was far less elegant.

“Aiji-ma,” Bren said, encountering them, and gave a little bow.

The dowager said, with a little inclination of her head: “The paidhi’s house is set in disarray this morning. One hears the lost are found. How are your people?”

“Well enough, aiji-ma, with thanks for the attendance of the physician.”

“One regrets the situation, nand’ paidhi.”

“On the other hand, aiji-ma, the stir did thoroughly beat the bushes. We know now things we had not known. One only deeply regrets the cost of it.”

“Indeed,” Ilisidi said grimly. “And my grandson has work to do, a great deal of work to do.”

“Our staffs should consult, aiji-ma.”

“Our staffs will consult,” she said. “Meanwhile my grandson will be making inquiries in Dalaigi. But enough business. We are here. We are alive this morning. Things might have gone differently.”

They had reached the door of the dining room. Bren stood just to the side to let the dowager and her escort, and Cajeiri and his, enter.

In that moment he caught a motion from the tail of his eye, Koharu and Supani coming fast.

He could not forbear a smile. Staff would not let him be caught at disadvantage. Supani whisked his day-coat off, Koharu helped him on with the jacket, just that fast, and he entered the dining room with the honor of the household assuaged, before his guests had more than reached their chairs.

He had noted a tableful of place settings. It turned out to be sufficient for all present, Cook’s sense of protocols, including their guests’ personal staffs. Suba thoughtfully stood in the service doorway to receive initial compliments, thus signaling he expected no further formal notice for this informal breakfast: only serving staff would interrupt them.

So Cenedi sat by the dowager. Therefore the Taibeni might sit with Cajeiri, Bren sat to himself, and there was hardly a word exchanged, while the initial serving—eggs—diminished.

“A bit of news. My brother has returned to dock,” Bren informed the dowager. “The report is that his boat has suffered damage. He may elect to come up the hill. One has advised him of hazard up here.”

“Damage,” the dowager said.

“One has no idea, aiji-ma, of extent or nature. One is concerned. But there is no word as yet.”

“The paidhi should remain here,” Ilisidi said firmly, “and let staff ascertain this.”

“One has sent a note down. We may hear during breakfast, aiji-ma.”

Tano and Algini might agree to go down: they could communicate. Most of the staff could not. But they might elect not to leave him. And Ilisidi was right: he had become a target.

Trust staff. Believe that his staff would not leave Toby and Barb unattended or their needs unguessed.

“Well, well, one hopes the damage is slight. No injuries?”

“Not that I have heard, aiji-ma.”

“Good, good.”

After that, and properly so, not a word of business else. The dowager put away a healthy breakfast, drank three cups of tea—Bren managed one helping and a half.

“We need not wait for removal of the dishes,” Ilisidi said. “We have business to undertake. Young gentleman, you may retire.”

Cajeiri’s mouth opened in dismay.

And silently shut. The head bowed. The young lord rose. His companions rose, and they all bowed in near-unison. “Yes, mani,” Cajeiri said.

That, perhaps, won redemptive points for the young gentleman. Bren sat still as the youngest left the table together. He did suffer a second’s concern, that it meant Cajeiri and his companions were now loose and unwatched, but there was a sort of rhythm to the young gentleman’s bursts of energy, and the youngsters this morning looked to be at a low ebb.

“One has heard from the dockside, nandiin,” Cenedi said, with a little tap at his ear and a glance toward Bren. “Nand’ Toby’s boat has suffered some hull damage. He and his companion are uninjured, but he and his companion are pumping some volume of water and continue to do so, while seeking a way to pull the boat up on skids. Local fishermen are assisting. Nand’ Toby has asked regarding your safety and the young gentleman’s, and has been reassured. Meanwhile Jago-nadi has been in contact with them by radio. They have indicated they came under attack, meeting hostile presence further down the peninsula, but that boat sank. The village has been alerted. So have other Guild.”

Other Guild. That would be the aiji’s forces. And a boat sunk. He was appalled.

“Did he say how it sank, nadi?” Bren asked.

“Apparently there are submerged rocks. The other ship hit the rocks.”

The old cottage industry of the area. The wreckers’ point. Fake lights, and natural currents that ran ships into trouble. “The Sisters. A little off the point of the peninsula, on this side. They turned short.” His heart had picked up a beat. He wantedto go down the hill and help—but there was too much going on. He wanted even more to haul Toby and Barb up to the house for safety, but if Toby’s boat had taken a scrape from the Sisters, it was lucky to be afloat, and the fight to save it could be desperate.

Most of all, he wanted to hear what had happened out there. Toby had charts. “Toby knows these waters, nadi. He would have known about the rocks.”

“Evidently the other boat did not,” Cenedi said. “It pursued, firing. And ran aground. Nand’ Toby came on in, as soon as he had made emergency repairs.”

God. What a mess! “One is grateful for the report,” he said. “My bodyguard is in debriefing and breakfast. One is sure you have heard from Nawari and Kasari, but mine will surely want to consult with you, Cenedi-ji, before all else.”

“Indeed,” Cenedi said. “As I understand it, nand’ Geigi’s yacht was still at its mooring when Banichi turned the situation at the estate over to the aiji’s menc so we are relatively certain that Lord Geigi’s is not the boat at the bottom of the bay. We suspect the boat may have been acting in concert with the incursion here, and launched much earlier—perhaps up from Dalaigi. We are attempting to learn. We are attempting to find any survivors.”

One got the picture: a two-pronged assault, one on the house, one to mop up if they had attempted to get out to sea. Toby had run right into the ambush.

“It was more than luck,” the dowager said, beginning to take a sip of tea. She did, then asked: “Do you, nand’ paidhic ?”

But then she set the cup down. It missed the table edge, fell onto the carpet, a soft thump. “Cenedi,” the dowager said quietly.

“The physician,” Cenedi said, dropping to one knee by Ilisidi’s chair. “Nand’ paidhi, may one beg you—”

“I can find him,” Bren said, and sprang up and went to the door, hailing a passing servant. “Mata-ji! Run to my aishid’s suite and if the physician is still there, bring him here, immediately!” He went looking for other servants, and sent them below, to find Siegi wherever he was and advise him to hurry.

But by the time he had gotten back to the dining room, Siegi was there, indeed, having come from down the hall. The physician was in the process of taking the dowager’s pulse—the cup, unbroken, had been set back on the table.

Bren stopped at the door and bowed, standing there quietly.

“Nand’ paidhi?” Ilisidi asked. “Come in. Come in.”

He did so. “Aiji-ma.”

“You were speaking of the Edi, paidhi. What did you intend to say?”

“It can wait, aiji-ma. May one suggest, a little restc”

“Pish! What observation, paidhi-aiji?”

Bren cast a desperate look at Cenedi, who gave him a distressed look back again, then bowed slightly. “One hopes,” Cenedi said, “that the paidhi having stated his opinion will lead to nand’ ’Sidi retiring for a few hours, since she did not sleep last night.”

Thump! went the cane on the carpet. “One hopes this report will lead to truth, ’Nedi-ji! And do not carry on conversation above our head! Paidhi, report!”

“One has had a thought, aiji-ma,” Bren said, “that Lord Geigi could get truth from the Edi staff, which the aiji’s men may not as easily come by. One proposes a phone call to the station, which I am prepared to make at a convenient hour. Geigi may well be abed.”

“Geigi can drag his bones out of bed at whatever hour things are afoot,” Ilisidi said. Her color was not, one observed, good. But her eyes flashed. “So can we! High time we did rattle our old associate out of his complacency. He relied upon this worthless nephew, and we are entirely out of sorts with him!”

Bren paid a second and apologetic glance toward Cenedi.

“At least,” Cenedi said unhappily, “it does not entail a trip overland.”

“One will make the call,” Bren said, “But—” He took such liberties with Tabini. He hesitated, with the dowager, but as the physician had stood up, he dropped to one knee by her chair, at intimate range. “Aiji-ma. A request. Once we speak to Geigi, you will retire for a few hours and get some rest. The dowager has been halfway across the continent and back, and camped out in a cold and unreasonably uncomfortable bus for hours and then suffered a ride which has all her young men and the paidhi nursing bruises. One by no means even mentions crashing through the garden shed. One begs the dowager, most earnestly, to take the opportunity to rest today while subordinates sort out the situation. We all may need the dowager’s very sage—”

“Paidhi-ji, you risk annoying us!”

“– advice, aiji-ma, and those of us who serve you would gladly risk your extreme displeasure to urge you to go to bed.”

“I concur,” Cenedi muttered. “Listen to the paidhi. You take his advice at other times. Take it now.”

A lengthy sigh, and a glittering sidelong pass of gold eyes beneath weary, slitted lids. “You are both a great annoyance.”

“But I am right,” Bren said. “And the dowager, being wise, knows it. Be angry with me. But one begs you rest while doing it.”

“Shameless,” Ilisidi muttered, and scowled at nothing in particular. “Well, well, let us call Geigi. And while we are about it, let us rouse out that scoundrel Baiji to the phone, and see what Geigi will say to his nephew. If that fails to enliven the hour, perhaps we shallgo to bed for a few hours.”

“Immediately, aiji-ma,” Bren said, and got up and headed out to his study, alone, scattering a trio of young male servants who had gathered in the main hall. “Bring Baiji to the study,” he said, “nadiin-ji, and you are instructed to use force should he object. Siton him, should he attempt to escape.”

“Nandi,” they said, astonished, and hurried off on their mission.

He entered the study, sat down, and immediately took up the phone.

Getting through to Mogari-nai offices took authorizations. Ramaso couldn’t do it without going through Shejidan; but he could. And when he had:

“This is the paidhi-aiji. Put me through to the space station.”

“ Nandi,” the answer came, a little delayed. “ Yes.”

And a few moments after that:

“ This is Station Central. Mogari-nai, transmit your message.”

“Live message, Station Central. Give me the atevi operator. This is Bren Cameron, key code under my file, BC27arq.”

A pause.

“ Confirmed, sir.”

The next voice spoke Ragi, and his request to that station roused out, if not Geigi himself, one of his personal guard, probably out of a sound sleep.

“ Is there an emergency?” the deep atevi voice asked in Mosphei’, and he answered in Ragi.

“This is the paidhi-aiji. This call is with the concurrence and imminent presence of the aiji-dowager. With apologies for the hour, we request Lord Geigi’s immediate response. The matter is of dire importance.”

“ We shall hurry, nandi,” the answer came, just that, and the speaker left the phone.

There was, now, a small stir at the door. It opened, and Bren punched the call onto speaker phone as the stir outside proved to be a scowling and unhappy Baiji, in the company of the three young servants.

“Nandi, we have had no breakfast, we have been subjected to—”

“Take a seat, nadi. That one will do.”

“Nandi!” Baiji protested. “We are by no means your enemy! We protest this treatment!”

“What you are, nadi, will be for others to judge,” Bren said, and noted a further presence in the hall, past the still-open door. “On the other hand, you may as well remain standing. The aiji-dowager is here.”

“Aiji-ma!” Baiji turned in evident dismay, and bowed, however briefly, as Ilisidi, not relying on Cenedi’s arm, appeared at Cenedi’s side in the doorway, walked to the nearest hard chair and sat down unaided, leaning on her cane. Cenedi took his usual post behind her.

“Aiji-ma, one protestsc”

“Silence!” Bang! went the cane. “Fool.”

“ Aiji-ma!”

“ Nand’ Geigi is present,” a voice said on speaker, and a moment later: “ Nand’ Bren. This is Geigi.”

“One rejoices at the sound of your voice, nandi,” Bren said. “The aiji-dowager is here with me. One regrets, however, to inform you of a very unfortunate situation: my life was attempted under the portico of your house, which is now, intact, except the portico, in the hands of Guild in the aiji’s employ. Among other distressing matters, I saw none of the Edi that I knew when I was there. More, your nephew has had certain communications with the Marid—”

“I am innocent!” Baiji cried. “ I am unjustly accused!”

“He is at my estate, under close guard, nandi, considering a negotiation regarding a Southern marriage, and the suspected importation of Guild of the Marid man’chi, and the ominous disappearance of staff loyal to you, nandi. One cannot adequately express the personal regret one feels at bearing such news.”

“ I rescued the aiji’s son at sea!” Baiji cried. “If I were of hostile mind, I would have delivered him to these alleged Southerners!”

“One might point out,” Bren said, “that I personally, aboard my boat, followed your nephew’s indication to locate and pick up the heir, who was at no time actually in your nephew’s hands. What he would have done had he been the one to intercept the aiji’s son is a matter of dispute.”

“Unfair!” Baiji protested. “Unfair, nandi!”

Ilisidi signaled she wanted the handset. Immediately. He picked it up, passed it over, and it reverted to handset mode, silent to the rest of the room.

“Nandi,” she said. “Geigi? Your nephew has become a scandal. Your estate reverts to yourcapable hands. Settle whom you wish in charge, exceptthis young disgrace! The connivance of the Marid to take this coast has continued and your nephew continues to temporize with the South as he did during Murini’s tenure. There was excuse, while Murini sat in charge, but this flirtation has continued into inappropriate folly and a reluctance to go to court. One cannot imagine what this young fool hopes to gain, except to extend the Marid into northern waters and settle himself in luxury funded by my grandson’s enemies!”

“I never did such things!” Baiji cried.

“And he is a liar!” Ilisidi snapped. Then she smiled sweetly, and extended the phone toward Baiji. “Your uncle wishes to speak to you, nadi.”

The servants who surrounded Baiji still did so, and Cenedi would not let Baiji touch the dowager, even indirectly: Cenedi transferred the phone to a servant, who gave it to Baiji, who put the receiver to his ear with the expression of a man handling something poisonous. His skin had acquired a gray cast, his face had acquired a rigid expression of dismay, and as he answered, “Yes, uncle?” and listened to what Geigi had to say, he seemed to shrink in size, his shoulders rounded, his head inclined, his occasional attempts to speak instantly cut off.

“Yes, uncle,” he said, “yes, uncle, yes, one understan—” A bow, a deeper bow, to the absent lord of his small clan. “Yes, uncle. One assures—uncle, one in no way—Yes, uncle.” And then: “They just left, uncle. One has no idea why. One did nothing to—” Baiji was sweating. Visibly. And Ilisidi sat there with the smile of a guardian demon, staring straight at him, with Cenedi standing by her side.