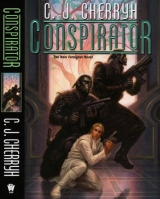

Текст книги "Conspirator"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“Halt!” a man said out of the dark behind them, just right behind them.

He ran harder, expecting to be shot at. But Antaro had stopped, and Jegari did, ahead of him, facing back toward him.

He stopped where Jegari stood, and looked back past Antaro.

A man rose out of the grass. He had what could be a rifle. He could have shot them, so things were not as bad as they could be—just stay alive, just keep himself and his companions alive. Mani was going to have to get them out of this one.

It was over. At least this round.

He stood still, panting hard. He could hear Jegari breathing.

He saw Antaro tamely fall in beside that man as he walked toward them, and he figured that man had threatened to shoot him and Jegari.

The man came right up to them. “Young lord,” he said, in an Eastern accent, and gave a sketchy, wary nod, and Cajeiri’s breath gusted out and didn’t come back for a moment.

The young man’s name was Heien. He was one of mani’s youngest, from Malguri.

“Come,” the young man said, “quickly.”

“There are men, nadi,” Cajeiri said, pointing, “further that way, moving northwest, toward nand’ Bren’s estate. Four men.”

“Hurry, then, young lord,” Heien said, and gathered him by the arm and dragged him into motion. “Quickly!”

Cajeiri ran, gasping as he did so, and Jegari and Antaro kept pace, but it was not far, just over a slight elevation, and there was the double track of the road through the grass, and of all things, the battered estate bus sitting in the middle of the road, where another road branched off and this one just kept going.

Had they even gotten beyond the estate road, with all their effort and their running?

Even before they got to the bus, more men were getting out—Cenedi was in charge of them. His pale hair showed, when little else did but shadows.

Cajeiri really ran, then, with all he had left.

The dowager had gotten up into the aisle and Bren deferred to her intention. “Ha!” was all she had said, when Cenedi told her that Heien had just swept up the youngsters. She had gotten up, painful as that process might be, and showed every inclination to go to the door and descend the steps. Bren, behind her, with Tano and Algini, waited in the aisle.

Some signal had passed, one of those prearranged sets of blips that the dowager’s guard used among themselves. And Bren ducked his head and asked, “Can you tell Banichi and Jago that we have them?”

“We have done so, nandi,” Tano said.

So Banichi and Jago did know the field was clear—the youngsters turning up was one of the eventualities for which they had arranged a code. Howthe youngsters had done it was something he was sure they were about to hear, in exquisite detail, once Ilisidi had given the princely ear a smart swatc

Or maybe she wouldn’t, for this one. Precocious lad. And the Taibeni kids—were Taibeni: out of their element in a state dinner, but not in moving across the country, thank God.

“Will Banichi and Jago come back now, nadiin-ji?” he asked Tano and Algini.

“They likely will not, nandi,” Tano said, and Algini:

“They are likely committed, now.”

“To what?” he asked.

“To removing these people from Lord Geigi’s estate, nandi,” Tano said. “The aiji’s men have likely moved up from the Township. The field is clear now. One doubts they will give up that advantage.”

Two of Cenedi’s men had gone with them– nottheir accustomed team—so both sets were working at personal disadvantage, and four of them were going to probe into the estate and attempt—

God. Bren bit his lip, knew he should not interfere in Guild operations, but, dammit—

“I did not approve this, nadiin-ji, this—extension of the mission.”

Algini said: “When the aiji requests it, nandic we are not his, but he can request it.”

Damn, he thought. He wantedthem back. He couldn’t bear it if he lost them. Couldn’t—couldn’t even think of it.

Cajeiri had come onto the bus to be shaken and thwacked by his great-grandmother on the bottom step—she was astonishingly mild in both. And then:

“Mani-ma, nand’ Bren, Guild is going toward the estate– nand’ Bren’s estate. They passed us.”

“On foot?” Ilisidi asked sharply, while Bren immediately thought of staff, of Ilisidi’s men—of the fact he had only half his bodyguard in a position to do anything about itc

“Yes, mani-ma,” Cajeiri said on a gasp for breath. “One is sorry. We were running. We were going therec and they were goingc ahead of us. East of the road.”

“Cenedi, did you hear?”

“Shall we move, aiji-ma?”

“Yes,” Ilisidi said sharply. “We shall.” She gave a shove to Cajeiri. “Get back there and keep quiet, boy. You and your companions are to stay low and stay quiet.”

Bren started to move. The knob of the dreaded cane came gently against his chest. “Paidhi-ji, we have resources, but this may entail damage to your estate.”

“The staff and villagers are my concern, aiji-ma. I told my brother to leave. One trusts he has done so.”

“Good,” Ilisidi said, and the cane dropped. Bren headed back to his seat, Tano and Algini preceding him, and he knelt with one knee in that seat as he reached it, facing them.

“How much can you advise them?”

“Nandi,” Algini said, “we can signal ‘base compromised’ and ‘base open.’ That is the best we can do.”

“They need to know that much,” he said. The bus engine started, the bus started to back and turn around, and he dropped to the seat and sat down. Tano moved up with him,another of Ilisidi’s men, in the scarcity of seats, sat down with Algini.

“Bren-ji,” Tano said, “one begs you will get down to the floor. We may take fire.”

It was an eggshell of a bus. There were already bullet holes perforating the door and sniper fire was a distinct possibility. That was true; and doubtless Cenedi, who still on his feet in the aisle, leaning over the seat behind the dowager and Cajeiri, was intensively debriefing the youngsters regarding what they had seen—how far back, how long ago.

Meaning what were their chances of the bus outracing a group of attackers moving in on foot?

Quite good, if the attackers hadn’t beenmoving for several hours. He thought about his assessment of more and higher-level Guild coming into the situation.

Bren dutifully got down on his knees, elbows on the seat, not a comfortable way to ride, but safer, considerably. Algini and the man behind, meanwhile, passed a heavy blanketlike affair forward, which Tano stood up to hook into the window frame. Small wonderthe baggage they had brought had weighed considerable. Another blanket was going into place on the far side. Not bulletproof, but certainly bullet-resistant, and protecting several rows of seats, notably the dowager and the youngsters, and him.

That secured, Tano sat down again.

“It is not entirely effective, nandi. One asks you stay as you are.”

It was uncomfortable. It was oppressive. It deprived him of all information about where they were. “Perhaps if we cut cross-country toward the village and came up to the estate from there,” Bren said, and then told himself just to be quiet and let people who knew what they were doing do their jobs.

“We may well do so, Bren-ji.” Tano was the gentlest of souls, given his profession; his voice relayed calm, even while the bus was bouncing along over unkept road and apt to come under automatic arms fire at any moment. “When we do exit the bus at the estate, kindly stay between us.”

“I have my gun, Tano-ji.”

“Rely on us, nandi.”

They had enough to worry about. He laid a hand on Ta-no’s knee. “Tano-ji. One relies on you both with absolute confidence.”

“One hopes so, nandi,” Tano said, and then there was an added energy to his voice. “We shall defend the house. Or take it back, if we come late.”

“One has every confidence,” he repeated. He didn’t want, either, to think of that historic residence occupied by persons bent on mayhem, its staff threatened and put in the line of fire. These were not fighters, the staff he had dispersed to this estate. They were brave; they had stayed by him during the worst of things, and taken personal chances rescuing his belongings, they were every commendable thing—but they were not fighters. They had nothing to do with the Guild.

Bounce and crash, potholes be damned. The speed their driver got from the overloaded bus was the very most it could do. It roared along with no care for the racket it made, bouncing over rocks and splashing through the remnant of rain puddles in the low spots, scraping over brush at the next rise, and rumbling over an ill-maintained bridge at the next low spot.

But at a certain point, after Bren’s knees had gone beyond pain from being bounced on the hard decking, and after the chill of that decking had migrated upward into his bones, they began to encounter brush that raked the side of the bus. One did not remember the brush being that close, and Bren twisted about, trying to see out the windshield, wondering whether they were still on the road at all.

Horrid jolt, and crash, and then the bus ran over something, multiple somethings that hit the undercarriage.

They were noton the road, and Cajeiri had flung himself over to assist the dowager.

“What did we hit, nandiin?” Cajeiri asked in distress.

“A stone wall, by the racket,” the dowager said. God knew– there was a hill out in the fallow land. There was the old road, where now only hunters ranged—but the wall had been timber railing.

“We have dropped out of contact with the house, nandi,” Cenedi said. “We are not going to the por—”

The nose of the bus suddenly tilted downward. No one of this company cried out, but Bren swallowed a gasp and grabbed the seat as they took the hard way down, through more brush.

He lost his grip: his head and back hit the seat in front, and Tano grabbed his coat and hauled him close to the seat.

“What are we doing?” he had time to ask.

“The estate road is a risk,” Cenedi said, holding himself braced in the aisle. “Get to your seat, young lord. And get down!”

“Yes,” Cajeiri said, and went there, handing himself across the aisle, and obediently ducking, with his companions.

They took another neck-snapping bounce, crashing through brush in the dark, scraping the underside of the bus, and when Bren looked around at the windshield, they had lost the headlights, or the driver had shut them down, never checking their speed.

My God, Bren thought, holding on, telling himself that atevi vision in the dark was better than his.

Another plunge, a hole, a fierce bounce and then a skid. He cast another look to the windshield.

The road. Even his eyes could pick up the smooth slash through the dark. They had swerved onto it—were ripping along it at fair speed. But where the hell were they?

Suddenly they turned. The bus slung everything that was unsecured toward the other side—Cenedi intervened, standing in the aisle, and supporting the dowager.

They hit a wooden wall, scraped through brush or vines or structure, and came to a sliding halt. There were lights– outdoor lights, from somewhere. They had stopped. The engine died into shocking silence, leaving only the fall of a board somewhere.

And then he realized they had just crashed through the garden gate of his estate, the service access at the back.

The bus door opened. Two shadows—Ilisidi’s men– immediately left the front seat and bailed out to take position.

Then people came running out of the housec notarmed, people in house dress, people he recognizedc

“They are ours, nadiin!” he shouted out, getting to his feet, as staff all innocent and alarmed, came to a halt facing leveled rifles.

“Quickly,” Cenedi said. “Disembark!”

“Go, paidhi,” Ilisidi said—practicality, perhaps, it being his estate, his staff: he steadied himself on Tano’s shoulder, and Algini’s arm as they sorted themselves out and headed for the bus steps.

“Nadiin-ji,” he said, descending.

“Nandi!” Ramaso’s voice. “Are you all right?”

“Everything is all right,” he saidc as boards went on creaking and settling. The stout pillars and vines of the arbor had withstood the impact. The garden wall and shed were not so sturdy. He found himself a little shaky getting down the steps and into the midst of dismayed staff.

“Rama-ji” he said. “We are a little ahead of possible attack on the house. Has anything happened here?”

“No, nandi. Nothing!”

“Get men down to the harbor, phone the village, and if you have not yet thrown the shutters, nadi-ji, do it now, as quickly as you can. We have the young gentleman safe, with his companions. Did nand’ Toby and Barb-daja get away?”

“Yes, nandi,” Ramaso said. “They have sailed.”

“Excellent,” he said. Thatproblem was solved. “Go. Quickly!”

“Nandi,” Ramaso said, and as Cenedi helped the dowager down from the bus, gave the requisite orders on the spot, distributing jobs, ordering guns out of locked storage, and telling three young men to get down to the dock, take the remaining yacht out to deep anchor and stay with it.

“Nadi.” Algini intercepted Ramaso as they walked, to give him specific orders for the securing of the house, the emergency bar on the kitchen door, Ilisidi’s men to have absolute access; and Tano said, urgently, seizing Bren’s arm.

“Stay under the arbor, Bren-ji.”

“We left men in charge here,” he protested.

“They are still there,” Tano said. “But take nothing for granted, Bren-ji.”

“Cenedi-ji,” Algini said. “If you will take the northern perimeter of the house, we shall take the main southern and center.”

“Yes,” Cenedi said, and hastened the dowager and Cajeiri along toward the house. Jegari and Antaro had caught up, and hurried. Bren lost no time, himself, with Ramaso keeping pace with him, along the main part of the arbor, into the house, the doors of which stood open.

They had not thrown the storm shutters. Those were going into place, one slam after another.

“Is there any dinner?” Cajeiri’s voice, plaintively. “One is very sorry, but we missed dinner.”

“We allmissed dinner, boy,” Ilisidi said peevishly.

“One can provide it,” Ramaso suggested, at Bren’s elbow, “in very little time.”

“For the guards stationed on the roof as well,” Bren said to him.

“So,” Ilisidi said with a weary sigh, as they reached the indoors, the safe confines of the inmost hall. “So. We shall meet at dinner, nand’ paidhi.”

“Aiji-ma.” He gave a little bow, half distracted, home, but not home: Banichi and Jago were still out there, at risk, and he wanted to know more than non-Guild was going to be allowed to know about what was going on out there.

Footsteps overhead.

“They are ours,” Cenedi said. “We are in contact.”

“Good,” he said. He worked a hand made sore by gripping the seat. “Good, Cenedi-ji. Aiji-ma, if you need anything—”

“We have all we need,” Ilisidi said, with her hand on Cajeiri’s shoulder. “We shall be in communication with my grandson once we dare pass that message, nandi.”

That was dismissal. Bren left them, headed for his own suite, as Ramaso turned up at his elbow. Tano turned up on the other side, staying with him.

“See to the dinner, nadi-ji,” Bren said to Ramaso. “If the enemy is moving out there, they will probably try us before morning. Four were spotted. There may be others. Let us take advantage of what leisure we have.”

“Yes, nandi,” Ramaso said. They reached the door of his suite, and even before the door had closed, Supani and Koharu turned up, solemn and worried-looking

He still had the blood from the early event sweated onto his hands and under his nails, the mud from the bus floor on his trousers—he was, Bren thought, a mess, the clothes were irrecoverable, and he was, despite the rapid movement getting in, cold to the core. A bath would be the thing, he thought; but he was not about to be caught in the bath by an enemy attack.

“Tano,” he said, “I shall be all right here. Go see to yourself. Help Algini. Be ready if Banichi and Jago need you. And have staff bring you something to eat. I shall be all right: I shall stay faithfully to this area of the house, excepting supper.”

“Yes,” Tano said. “But, Bren-ji, in event of trouble, take cover. Do not attempt to fire. Rely on us.”

“Always,” he said with a grateful look, a little instinctively friendly touch at Tano’s arm: he was that tired. “One has no idea how long this night may be. One promises to be entirely circumspect.”

“Bren-ji,” Tano said, and made a little bow before leaving.

Bren peeled off the coat. The lace cuffs of his shirt were brown and bloodstained.

“Hot, wet towels, here, to wash with in the bath,” he instructed the two domestics. “For Tano and Algini, too, if they can find time. Moderate coat and trousers.” He walked on to his bedroom and took the gun from his pocket, laying it on the dresser. “This I shall need.”

“Yes,” they said, and Supani went on toward the bath while Koharu helped him shed his boots and peel out of his hard-used clothes.

Appearances mattered. The staff was possibly going to be at risk of their lives, and theirlord was obliged to look calm and serene, no matter what was going on.

He bathed not in the tub, which would have taken time to fill, but within it, with running water and a succession of sopping towels, had a fast shave—he did that himself, with the electric—and flung on a dressing gown, trusting the pace Koharu and Supani had set to get him to the dining room in good order.

Somewhere out in the rocks and bushes, somewhere near the intersection of roads they had dodged, coming overland, or maybe up toward the train station, and on Lord Geigi’s estate, action was probably already going on—action was too little a word. The first moves of something far, far larger, if he read it right.

Banichi and Jago—

He hoped they weren’t taking chances out there. Lord Geigi’s Edi staff was on their side: they well knew that; but that was another question. They had seen no one they recognized from Lord Geigi’s tenure. If there were Edi about, where were they? What had become of them?

Banichi and Jago were still obliged to be careful about collateral damage. So were Tabini’s forces. If there was one solitary thing he could think to comfort himself, it was that there would not be random fire incoming in that situationc but it made it doubly dangerous, necessitating getting inside. Finesse, Banichi called it.

God, he didn’t want even to think about it.

He left a soaked pile of dirt-smeared towels in the tub and headed out to his rooms to dress, with staff help. It was surreal. Attack was likely coming, and so far, everything stayed quiet, quiet as any night in the house.

But he tucked the gun into his coat pocket when he had finished dressing, dismissed Supani and Koharu to go get their own supper, and, going out into the hall, suggested to the few younger members of staff who stood about looking confused and alarmed, that they might usefully occupy themselves by removing porcelains and breakables to the inner rooms. “Just put them in the cellar, nadiin-ji. One cannot say there will be disturbance inside the house at all, nadiin, but one hardly knows. And at the first alarm, go immediately to the cellar and stay there with the door shut, one entreats you. I would sacrifice any goods in this house to preserve your lives.”

“Nandi,” they said, and bowed. He headed for the dining room.

In fact, he and the dowager arrived at the same moment, himself alone, the dowager accompanied only by two of her youngest bodyguards; and Cajeiri and the two Taibeni youngsters, who had almost matched the paidhi in dirt, immaculately scrubbed and dressed, likely having used the servants’ bath.

“Aiji-ma,” Bren said, bowing to the dowager. Staff had laid the table for three, the two Taibeni to stand guard with the two senior guards. Only the paidhi was solo—absolute trust for the security that was on duty; and a lonely feeling. Tano and Algini were in quarters, likely trying to monitor what was going on while the dowager’s men, under Cenedi’s direction, took defensive precautions.

And still no word from Banichi and Jago. He wished he could haul them out of wherever they were, whatever they were into, and let the aiji’s guard handle the mess at Lord Geigi’s estate. He was too worried for appetite. Given his preferences, he would have paced the floor. Sitting down to dinner was hard—but at this point necessary—besides being a demonstration of confidence for the staff.

The before-dinner drink, a vodka with fruit juice—that came welcome.

Supper consisted of a good fish chowder and a wafer or two, warm, filling, and quick. He took his time, somewhat, in general silence, in pace with the dowager, while Cajeiri wolfed his down with a speed that drew disapproving glances.

“Such concentration on one’s dinner,” Ilisidi remarked.

Cajeiri looked at her, large-eyed. “One was very hungry, mani-ma. One sat in that tower forever.”

“Tower,” Bren said.

“In the garden, nandi. We went over the wall and through the woods. We hid in a tower on the wall.”

“You have gotten quite pert,” Ilisidi said. “Have we heard an apology, boy?”

Cajeiri swallowed a hasty mouthful and made a little bow in place. “One is very sorry for being a problem, mani-ma, nand’ Bren.”

“How did you separate yourself?” Ilisidi asked. “ Whydid you separate yourself.”

“One—hardly knows, mani-ma. May I answer?”

At the table, there was properly no discussion of business. And the dowager’s table was rigidly proper.

“Curiosity overwhelms us,” Ilisidi said dryly. “You may inform us. We shall not discuss.”

“There was the bus, and Jago, and nand’ Bren, and Banichi; and the shooting started, and the bus was hit, and one just—we just—we just—the bushes were closer. We thought they would fight.”

It was a fair account. And contained the missing piece. We thought they would fight. He’d assumed Banichi would go for Cajeiri; and the kid had equally assumed Banichi wouldn’t. And the kid had assumed they were going to stand and fight, so he’d taken care of himself.

Ilisidi simply nodded, thoughts flickering quickly through those gold eyes.

“Indeed,” she said. “Indeed. One expected a sensible boy would then find his way down the road.”

It was more than the paidhi had expected of a boy. A lot more.

“One did, mani-ma. As soon as it was dark.” Cajeiri’s brows knit. There was something more to say, something unpleasant, but he didn’t say it.

“May one ask, young gentleman,” Bren said, “what you have just decided not to say?”

A flash of the dowager’s eyes, which quickly settled on Cajeiri.

“One fears one may have caused a serious accident to a man on the roof. One hopes they were the enemy.”

“What time was this?”

“Right at dusk, nandi. He was on the roof. He probably fell off.”

“Good,” the dowager said, taking a drink. And added: “Hereafter, you will have your own security.”

“Antaro and Jegari, mani-ma—”

“You are beginning to think independently. These young people will benefit from senior Guild constantly attached to you, young man. This should have been done before now.”

“Not Great-uncle’s! One asks, not Great-uncle’s!”

“No,” Ilisidi said, “ notAtageini. Nor Ragi. Malguri.”

Oh, that was going to be an explosion, once Tatiseigi heard hisgreat-nephew was dismissing his Atageini guards; and once Tabini andthe Taibeni heard that the senior pair in his son’s bodyguard was not going to be Ragi atevi, from the center of the aishidi’tat, but Easterners—that explosion would be heard end to end of the Bujavid, and Ilisidi’s opinion might not, for once, prevail.

The paidhi was going to stay well and truly outof that argu—

Quick footsteps sounded in the halls. One of the serving staff came in, breathless, bowed once to the dowager and once to him. “Nandiin. Movement is reported across the road.”

He cast a worried look at Ilisidi, whose face remained impassive. He swallowed the bite he had and with a little bow, got up from table.

The dowager likewise rose, Cajeiri offering his hand beneath her elbow as she gathered up her cane.

“Aiji-ma,” Bren said, “one would suggest the office, which has no windows: there is a comfortable chair, and the staff might provide an after-dinner brandy.”

“An excellent notion, paidhi-ji.” One earnestly hoped the dowager would provide sufficient psychological anchor for her great-grandson to keep his burgeoning personality from flaring off down the halls to help them out. Clearly, the paidhi had not been adequate to keep him from picking his own course. Cajeiri had been looking for cover when the shooting started, not looking for direction from the paidhi-aiji. So write the paidhi off as a governance. Write off the boy’s most earnest promises: one suspected he was hitting an instinct-driven phase.

“Go,” Ilisidi said as he lingered, ready to assist her. “Go, nand’ paidhi. We are just moving a little slower this evening.”

“Aiji-ma.” He bowed, then left with the anxious servant, asking,

“Where are Tano and Algini at the moment, Husa-ji?”

“In the security office, nandi, one believes.”

In most houses, that was near the front door. In this one, by revision, it was a comfortable nook in the suite his bodyguard used, a left turn at the intersection of halls.

“Carry on, nadi,” he said to the servant, “with thanks. Check the garden hall locks. Put the bar down.”

“Nandi,” the servant murmured, and diverged from his path.

That beautiful glass window offered a serious compromise to house security. That was why there was a very stout mid-hallway set of doors to close the garden hall, with deep pin-bolts above and below and a sturdy cross bar that resided upright in the back of the right-hand door. The two doors that led off that hall, one to the kitchens and the other to the staff rooms, had equally stout single doors, as solid as if they were opposing the outside worldc which, being next to more fragile sections, they were counted as doing.

The last of staff was on their way to defensive stations or to cover. Those last doors were about to shut. Kitchen would not be gathering up the dishes. They would be sealing themselves in from both sides.

He turned his own way, his bodyguards’ door being wide open. He entered without knocking, into the little security office where Tano and Algini had set up their electronics, black boxes of all sorts, and a low-light monitor screen.

No need to tell them what was going on. And if they had wanted that door shut yet, they would have shut it.

They acknowledged his presence with nods of the head, that was all, eyes fixed on their equipment, and he slipped into the nearer vacant chair and watched the monitor. He didn’t see anything but shrubbery and a small tree. The view changed to the front door. The garden, and the damaged arbor.

“Have you contact, nadiin-ji, with the aiji’s forces?” he asked.

“Cenedi has,” Tano said, and added, after a moment, “Banichi has now missed a report, Bren-ji. We are not greatly alarmed, but we are obliged to say so.

He didn’t want to hear that. He bit his lip in silence for a moment, and forbore questions. Their eyes never left the equipment, with its readouts and its telltales.

“The roof still reports all quiet, but movement on the perimeter,” Algini said. “We remain wary of diversionary action. Two of Cenedi’s men are interrogating Lord Baiji. And names are named.”

“Report as you find leisure,” Bren murmured, meaning he would not ask for a coherent report, busy as they were. He was in the nerve center of their defenses. Some of those lights represented certain points of their defense. The monitor showed a view of the stone walkway that led down to the harbor and the boat dock.

Movement somewhere, though it didn’t show at the moment.

“Where is the dowager, Bren-ji?” Tano asked.

“The office,” he said, “with Cajeiri. Staff hall doors, garden doors, front doors, all shut and secured.”

“Tano-ji,” Algini said sharply, calling for attention. Both brows furrowed, and the pair exchanged looks, a shake of the head. Bren sat very still. Didn’t ask. They were busy, both of them, at their specialty, and Cenedi’s men were out and about, including on the roof, including down toward the dock, and some likely in the village. Right now, having been left in charge of his safety as well as their regular duties, they needed no divided attention: needed to know where he was, and that he wasn’t in need of their help. That door to the hall was open, but it, like the other secure doors, was steel-cored, capable of being shut and security-bolted.

What they had in that console, whether it was officially cleared, he had no personal knowledge, didn’t technically understand, and frankly hadn’t asked—deliberately hadn’t asked. Tano and Algini had spent the last couple of years on the space station. While the planet below them had broken out in chaos, they’d spent their time becoming familiar with equipment the paidhi, who was responsible for clearing new tech to be generally deployed on the planet, had never clearedc and under the circumstances of their return from space, he hadn’t asked.

Hypocritical? He had no question it was. But maybe he should have—considering that Captain Jules Ogun, in charge of the space station, had decided to drop relay stations on the planet. Maybe he should have asked what part Tano and Algini had played in that decision, whether they hadadvised Lord Geigi, governing the atevi side of the station, that this communications system was a potential problem.

Mogari-nai, the big dish, had been their sole contact when they’d left for deep space: now, with the proliferation of satellites—God knew what was going to be loose in the world.

Things that threatened the operation of the Asassins’ Guild, which hadn’t had to worry about locators. Or cell phones. There was a time they hadn’t had night-vision, or a hundred other items he suspected his own security staff and Geigi’s now had—and he hoped no one else did.

But hehad been out in space for two years, leaving the job of determining what technology ought to go to the planet largely to Yolanda Mercheson, essentially an emissary of Captain Jules Ogun. More, once the coup had happened, she’d interfaced—not even between Mospheira and the atevi—but mostly between the humans of her own ship and Lord Geigi, whose eagerness to snatch whatever tech he could lay hands on was only surpassed by that of Tabini-aiji himself.