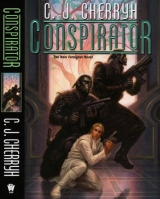

Текст книги "Conspirator"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

Baiji had looked a little askance at Banichi’s departure, his eyes flicking to that doorway.

“So we must,” Bren said, “with greatest thanks, be on our way back to Najida, to attend to my other guests. Shall we see you in Najida?” Not while the dowager was there, for certain. But he could deliver her message. “Or perhaps in court, when the session opens?”

“One hopes,” Baiji said fervently, “one hopes so. Please convey my earnest good will to the aiji-dowager, and, young gentleman, to your esteemed father.”

Profoundly sweating.

Not right, Bren thought. It was time to go. And Banichi had not come back in, but Jago had begun to move toward the door. So, with her, and looking just a little on edge, the Taibeni youngsters moved. Cajeiri might or might not have noticed that action. He was sitting at Bren’s right, and his expression was not readable—one hoped he was not fidgeting anxious glances toward the doorway, where Banichi was, perhaps using his old contacts in the house, Geigi’s Edi contacts, to ask some pointed questions.

But it was his job to read the signals and get them out of here. He stood up.

“One will be most anxious,” Baiji said, rising as Cajeiri rose. “Please convey our most fervent wishes for the aiji-dowager’s good will. We had sickness in the house this winter. Please assure the dowager missing the session had nothing to do with political opinion. We feared to bring a contagion to that august assemblyc”

“Certainly one will convey that information,” Bren said, laying a hand on Cajeiri’s shoulder, steering him toward the door. He put a little pressure on it, just a brief warning signal, trusting the lad not to flinch. “We shall, shall we not, young lord?”

“Yes, nandi, indeed.” Cajeiri properly bowed toward their host, and Bren bowed, and turned the boy toward the door, where he hoped to God that Banichi was waiting. He didn’t like what he was getting from Baiji. Not in the least. Jago opened the door, and they exited into the tiled hall with the potted plants.

“Nandi,” Baiji said, at their backs, hurrying to overtake them as they headed for the front doors. The servants were at the front doors. Banichi and Lord Baiji’s guard were engaged in conversation there, and Banichi had to have realized they were leaving.

But overtake them Baiji did, just short of Banichi and the guards—but Jago turned suddenly and interposed her arm, blocking his path.

“Please!” Baiji protested. “Nandiin, let me escort you to your bus. We are so very pleased that you have come, and we hope to visit while the young gentleman and the aiji-dowager are in residence, if you would be so good, nandi, as to relay my sentiments to herc”

“Excuse me, nandi,” Jago said, maintaining her arm as a barrier. Her other hand was near her holster—not on it, but near, and she kept it there. Cajeiri’s young staff were in danger of getting cut off by Baiji’s three remaining guards, who were behind Baiji. “Come,” Jago said sharply. “The paidhi has a schedule to keep, nadiin-ji. Come.”

The youngsters hurried to catch up—inserted themselves right with Jago.

“Please,” Baiji said, actively pursuing as they walked toward the doors. “Please, nand’ paidhi. Something has alarmed your staff. In the name of an old alliance, in the name of my uncle, your neighbor, allow me a word. Nandi! Nandi, I havemet with the Tasaigi. I confess it!”

Tasaigi. The front doors had opened. But at that name out of the hostile South, Bren stopped, cast an astonished look back.

“But one refused them, nandi! Your presence has lent this house strength! Please! Do not desert us!”

He had stopped. Jago had stopped. Banichi held the doors open. And he needed urgently to get the boy out of here.

“Please, nand’ paidhi! Nandi, be patient, please be patient and hear me out! They are gone now, they are gone! I sent them off. It is all safe!”

“We cannot wait for this.” The door remained open: Jago held Baiji back; and now Jago did have her hand on her pistol, and quietly, deliberately drew it. The two Taibeni youngsters were as helpless as Cajeiri, caught in the middle, trying to figure out where they should be, which turned out to be against the wall. And he hesitated two breaths for a look back. “We can discuss it when you visit Najida.”

“Nandi, it may be too late! My uncle—my esteemed uncle– the position he occupies. He protects us. But he draws attention. Oh, favorable gods!” The fellow was sweating, and looked altogether overwhelmed, perhaps about to collapse on the spot: but his bodyguard had frozen in place behind him. “Oh, good and auspicious godsc”

“Out with it!” Bren said, with a worse and worse feeling that they were dealing with a fool, and one that might not survive, left alone in this house, having named that name. “I shall hear you, nand’ Bajji, for your uncle’s sake, and for your service to the aiji’s house. I shall hear you at length and reasonably, for your uncle’s sake, when you visit us in Najida.” Take him with them? Be surethat they heard whatever truth he had to tell, before Tasaigi agents caught up to him? “The truth, nandi, only the truth will serve you at this point—only the truth, and do not delay me further! In two words, tell me what I should hear. Tell me what you know Lord Geigi himself would wish to hear, because I assure you he willhear it.”

“Nandi, your great patience, your great forbearance—”

“Have limits. What have you doneregarding the Tasaigi, nandi?”

“Nandi, please hear me! I—dealt with the South during the usurper’s rule, that is to say, I dealt with them in trade, I received them under this roof, I encouraged them—I did shameful things, nand’ paidhi, because we were, all of us on this peninsula, under threat! It was rumored, nandi, it was greatly rumored at one time that Tabini-aiji might have come to your estate!”

“He did not.”

“But it was rumored! And we were all in danger, your estate, most of all.”

News. He had not heard anything about a Tasaigi intrusion here. “And?”

“And we—we feared every day that the Tasaigi might be encouraged to make a move against the township, and this whole coast. We expected it. Instead—instead—they wrote to me requesting I visit.”

“And you went to them?”

“If I refused them, it would be a matter of time before they sent assassins, nandi, and without mec not that I in any way claim the dignity or honors of my uncle—but without me– nandi, I was the only lord in the west, save Adigan up at Dur, to hold his land safe from invasion. The northern peninsula, that went under: the new regime set up new magistratesc”

“You are wasting my time, nandi. All this I know. Get to it! What have you done?”

“So I met with them, nand’ paidhi, being as good as a dead man otherwise, and hoping—hoping to negotiate some more favorable situation for this district. I reasoned—I reasoned as long as I was still in power here, it would be better than one of their appointed men, would it not?”

“Undoubtedly.” Taking him with them to Najida might indeed be the best thing. If there was a problem on staff, it might find Baiji before nightfall.

Or find them, if they didn’t get the hell out the door Banichi was holding open.

“So I met with them.”

“We have been to this point three times, nandi. Get beyond it!”

“They offered me—being without an heir—they offered me an alliance. They—offered me the daughter of a lord of the South, and I—I said I wished to meet this young woman. I did anything I could think of and objected to this and that detail in the contract—”

“You stalled.”

“Nandi, I—ultimately agreed to the marriage. Which I did not carry out. But I know that I have put this young woman—a very young woman—and her family—in a difficult position. Which they urge is the case. So—”

It could go another half hour, round and round and round with Baiji’s ifs and buts. “ Theyhave put this young woman in a difficult position, nandi. You are not morally responsible. And one will discuss this at length in Najida. Order your car, nandi, and join us there, should you wish to discuss it further. I will not stand in the hall to discuss this.”

“One shall, one shall, with great gratitude, nandi, but let me go withyou!”

“This is enough,” Jago said in the kyo language, which no Guild could crack—but which all of them who had been in space knew. “Nandi! Go!”

“Good day to you,” Bren said, and with his hand firmly on Cajeiri’s shoulder, steered him out the door, where to his great relief Banichi closed in behind them all and let the door shut.

It immediately reopened. “Nandi!” Baiji called at their backs, and Jago half-turned, on the move. “I shall go with you. Please.” Baiji ran to catch up.

“Stay back!” Jago said, and Bren glanced back in alarm as Jago’s gun came up, and Baiji slid to a wide-eyed, stumbling halt just this side of the doors, none of his guard in attendance.

Bren turned, drew Cajeiri with him, and Cajeiri looked back. The Taibeni youngsters were trying to stay close.

Meanwhile their bus, parked out in the sunlight of the circular drive, rolled gently into motion toward the portico.

A sunlit cobblestone exploded like the crack of doom. Bren froze, uncertain which direction to go.

A whole line of cobbles exploded, ending with the moving bus—which suddenly accelerated toward the portico with a squeal of tires. Fire hit it, stitched up the driver’s side door, and it braked, skidding sidelong into the right-hand stonework pillar with a horrendous crash.

The whole portico roof tilted and collapsed in a welter of stones and squeal of nails, the collapsing corner knocking the bus forward. In that same split-second Banichi turned and got off three shots up and to the left.

An impact hit Bren from behind—hit him, grabbed him sideways as if he weighed nothing and carried him the half-dozen steps to the bullet-riddled side of the bus—then shoved him right against it. It was Jago who had grabbed him, Jago who yanked the bus door open while the portico resounded with gunfire.

“Get in,” Jago yelled at him, and shoved him inside, and he didn’t argue, just scrambled to get in past the driver’s seat, and down across the floor. Their driver was lying half over the seat in front. Jago had forced her way in, and threw the man onto the floor, as Banichi got in. Bren got a look past his own knee and saw Banichi lying on the steps holding someone in his arms.

Jago jammed on the accelerator and snapped his head back, tumbling him against the seats. The bus lurched forward, ripping part of the bus roof and pieces of the portico ceiling, tires thumping on cobbles as they drove for sunlight and headed down the drive.

Glass broke. Bullets stitched through the back of the bus, blew up bits of the seats and exploded through the right-hand window.

Jago yelled: “Stay down!”

They hit something on the left and scraped along the side of it—the bus rocked, and Bren grabbed the nearest seat stanchion, sure they were going over, but they rocked back to level, on gravel, now, three tires spinning at all the speed the bus could manage and one lumping along with a regular impact of loose rubber.

But they kept going. Kept going, and made it to the gate.

Bren looked back, then forward, trying to figure if it was safe to move yet, trying to find out was everybody all right.

Banichi had edged forward, on his knees, and the person he had wasc Baiji.

Baiji. Not Cajeiri.

“ Where is Cajeiri?” Bren cried, over the noise of the tires on gravel, one flat, and past the roar of an overtaxed engine. “ Where is Cajeiri, nadiin-ji?”

Banichi was on his knees now, trying to staunch the blood flow from their wounded driver, whose body only just cleared the foot well. Jago drove, and as a disheveled Lord Baiji tried to crawl up the steps and get up, Banichi whirled on one knee, grabbed the lord’s coat and hauled him down, thump! onto the floor, with no care for his head—which hit the seat rim.

Baiji yelled in pain, grabbed his ear. His pigtail having come loose, its ribbon trailed over one shoulder, strands of hair streaming down beside his ears.

But no view, before or behind, showed the youngsters aboard the bus.

“Banichi!” Bren breathed, struggling to both keep down and get around to face Banichi, while the bus bucked and lurched over potholes on three good tires.

“He ran, Bren-ji.” Banichi didn’t look at him. Banichi concentrated on the job at hand and pressed a wad of cloth against the driver’s ribs, placing the man’s hand against the cloth. “Hold that, nadi-ji, can you hold it?”

A moan issued from their driver, but he held it, while Banichi tore more bandage off a roll.

They owed this man, owed him their not being barricaded in Kajiminda with God-knew-what strength of enemy.

But the youngsters were in that situation. All three of them. And Banichi and Jago had left them there.

“Were they hit?” he asked Banichi. It was the worst he could think of.

“The boy will have taken cover. He is not a fool.”

And was Baiji their hostage, intended to get Cajeiri back? What the hell were Banichi and Jago thinking?

He didn’t know. He couldn’t figure. He’d been about to look around for them when Jago had hit him and carried him forward, straight into the bus. He was stunned, as if something had slammed him in the gut. His heart was pounding. And he kept thinking, This can’t be real. They can’t have left the kids. They can’t have left them there.

He sat on the cold, muddy floorboards, with their driver’s blood congealing in the grooves in the mat, trying to think, trying to get his breath as the bus slung itself onto the potholed estate road and kept going. Banichi got up for a moment and pulled the first aid kit from the overhead, with the bus lurching violently and what was probably a piece of the tire flapping against the wheel well at the rear. Banichi got down and started to work again, got the man a shot of something, probably painkiller.

They reached the intersection and took a tolerably cautious turn onto that overgrown road, and then gathered speed again.

They’d lost Cajeiri. They’d grabbed Baiji.

And the hell of it—he, who was supposed to understand such things, didn’t know why in either case.

Chapter 10

« ^ »

Firing had been deafeningc and now it was silence, with people moving about. Cajeiri had no view of the proceedings, nor any inclination to make any noise, not even to rustle a dry winter twig. He was flat under the front shrubbery with his chin in the dirt, and Antaro and Jegari were lying on top of him. The roof had come down on the bus—he had thought it was wrecked. But it had gotten away. He had struggled briefly just to turn his head to see what was going on, but thick evergreen was in the way.

Then he had heard the bus take off again. Either the driver alone had gone for help from Great-grandmother, or Banichi and Jago had gotten nand’ Bren into the van and taken off. He should not have dived for the bushes. He had thought the bus was finished.

And now that it had gone, that left him and his companions, as Gene would say, in a bit of a pickle.

A fairly hot pickle, at that. A whole dish of hot pickles.

He rested there, struggling to breathe with the combined weight on his back, trying to think.

Going back into the house, even if things were quiet, and just asking the Edi staff: “Did you get all the assassins?” did not seem the brightest thing to do.

Damn. It was very embarrassing to die of stupidity—or to end up kidnapped by scoundrels. Again.

What would Banichi do? That was his standard for clever answers. Banichi and Jago and Cenedi.

They’dprobably moved fast for that bus, that was what they’d likely done. He remembered its motor still running. He hadn’t marked that. He’d thought it had been crushed by the roof when it came down. It must have been able to move. They’d have gotten nand’ Bren there, fast, and one of them would have been shooting back, which would be why the fire had been going on as long as it had—he was mad at himself. He could think of these things. But he should not take this long to think of them. If he had been thinking fast enough they would be on that bus, and headed for nand’ Bren’s estate.

So could he not think aheadof the next set of events?

It would be really, truly useful if he could. All Jegari and Antaro were thinking of right now was keeping him alive and trying to get him somewhere safe, but they were in a kind of country they had never seen before—neither had he—and he did not think he ought to take advice from them, not if it sounded reckless. There were times to be reckless. There were times to be patient. And this seemed maybe one of those times to be very, very patient.

He was afraid to whisper and ask them anything. The Assassins’ Guild used things like electronic ears, and might pick him up. Once that bus got to the estate, there would be a rescue coming back, that was sure; and maybe Banichi and Jago and nand’ Bren were still here, hiding somewhere nearby, themselves, just waiting for reinforcements, if the bus had gone and left them.

That meant he and his aishid had to avoid being found and used as hostages, and if they moved at all, they had to do it extremely quietly.

Voices were still intermittently audible: someone was talking unseemly loudly in the hallway, and the doors of the house were still open. It might be staff. But if the lord of the house was giving orders, did it not make sense he would now order the doors shut, for protection of the staff who were in the house?

“Is it safe?” one asked, which indicated to him that they had to be worried about being shot, and thatmight mean staff had not been in on the plot.

It did not mean that nand’ Baiji had not been in on it—nand’ Bren had told him there might be faults of character in nand’ Baiji, and it was very instructive, lying here on the cold dirt, under the weight of two people trying to protect him, and with the smell of gunpowder wafting about. Great-grandmother had held up faults of character– ukochisami—as a thing he should never be thought to have. And now that he had a shockingly concrete example of a grown man with faults of character, he began to see how it was a great inconvenience to everyone for a man to have such faults, and to be a little stupid, too, another thing of which Great-grandmother greatly disapproved. To have faults of character andto be a little stupid, while trying to be clever—that seemed to describe Lord Baiji.

And he thought that Lord Geigi, his uncle, up on the station, must have been at a great loss for someone better to leave in charge on his estatec that, or Lord Baiji, being a young man, had been a little softc Great-grandmother was fond of saying that soft people easily fell into faults of character and that lazy ones stayed ignorant, which was very close to stupid.

Great-grandmother would have thwacked Baiji’s ear when he was young, no question, and told him what she had told him: If you intend to deal sharply with people, young man, deal smartly, and think ahead! Do not try to deal sharply with us, nor with anyone else smart enough to see to the end of matters! You are outclassed, young man, greatly outclassed, and you will have to work hard ever to get ahead of us!

It was absolutely amazing how Great-grandmother could foresee the messes and the bad examples her great-grandson could meet along the way. Ukochisamadid describe Baiji, who had described a fairly good plan, a policy of stalling the Southerners and keeping them from attacking, but it would not have gone on forever. He would eventually have had to marry that Southern girl, who would be either extremely clever herself, or extremely stupid—and her relatives would just move right in.

Perhaps they had. One had a fairly good idea that the Southerners were somewhere in this situation. And one began to think—there had been very few servants in sight. They had not said very much. Baiji had let the roads go and he had told nand’ Bren it was because people had gone to relatives down in the Township during the Troubles and things had gotten out of hand.

That meant—maybe there were not many Edi folk in the house.

Or maybe there were none. Maybe those had been Southern servants. Southern folk had an accent. But you could learn not to have an accent.

The only thing was—Baiji had saved his life, when they had been about to sink out there in the sea.

Baiji had told nand’ Bren where to look for them.

But maybe Baiji had hoped to get to them first, for completely nefarious reasons—nefarious was one of his newest words. Maybe Baiji had had them spotted and was trying to get there ahead of Bren and sweep him up, or maybe just run over the little sailboatc while pretending to be rescuing him.

That had not happened, at least. And Baiji couldhave kept the information to himself.

That was confusing.

Baiji had trailed them out the door, pleading with nand’ Bren, before the shooting started. It had gotten confused then, and his memory of those few moments was a little fuzzy, but had not Baiji been talking about his engagement to that Southern girl and asking to go with them?

“Should we call the paidhi’s estate?” one of the servants asked, standing near their hiding place in the bushes. He had heard the Southern accent. The Farai had it. And that was not it. Maybe it was Edi. And another voice said: “Ask the bodyguard.” And a third voice, more distant, from what seemed inside the foyer: “No one can find them.”

That could mean anything. It could mean Baiji’s bodyguard had taken him and runc somewhere safe, like clear away and down to the Township, or to some safe room: great houses did tend to have such.

It could also mean Baiji’s bodyguard had been in on the attack and were somewhere around the estate hunting for nand’ Bren. Or for him.

That was a scary thought. He was cold through, in contact with the dirt. He started to shiver, and that was embarrassing.

“Are you all right, nandi?” the whisper came beside his ear.

He reached back blindly, caught Antaro’s collar and pulled her head lower, where he could whisper at his faintest. “We must not move until they shut those doors,” he said.

“Dark will not be safe,” Antaro whispered back. “The Guild has night scopes. We will glow in the dark.”

“We need full cover,” he whispered. “Did nand’ Bren get away, nadi?”

“His guard took him,” Antaro said. “They left.”

That was good and bad news.

“They will come back,” he said. “My father will send Guild. We have to stay out of sight.”

“Wait until they all go in. Then I can go along between the bushes and the wall and see how far we are from the edge of this place.”

“There might be booby traps,” he said. “Banichi taught me. Watch for electrics, watch for wires.” He heard the doors shut with great authority and that was a relief. For a few heartbeats after that it was just their own breathing, no sound of anyone any longer outside, just the creak of the wreckage settling: that was what he thought it was.

“I shall go, nandi,” Antaro said. She had had someGuild training. Far from enough.

“One begs you be careful, nadi.”

It took some careful manuvering: she slithered right over him, and it was very, very dangerous. They were behind evergreens, on a mat of fallen needles and neglect. That could mask a trap, and Antaro necessarily made a little noise, and left clear traces for somebody as keen-eyed as Banichi. That was a scary thought, but it was scarier staying here once night fell and nand’ Bren came back and bullets started flyingc not to mention people using night scopes on the bushes.

Antaro reached the end of the building, and Jegari, still on top, pushed at him, insisting it was his turn. So he moved. He saw no threatening wires. There was a wire that went to some landscape lights. But nothing of the bare sort that could take a finger. Or your head. He slithered as Antaro had done, as Banichi had taught him, intermittent with listening, and he was fairly certain Jegari moved behind him. He crawled past the roots of bushes, and along beside the ancient stonework of the stately house, trying to disturb as little as possible with the passage of his body, trying to smooth down the traces Antaro had left, and hoping Jegari would do the same, on the retreat.

Antaro, having reached the corner, had stopped. A little flagstone path led off the cobbled drive, and passed through an ironwork gate, a gate with no complicated latch.

That gate was in a whitewashed wall as high as the house roof, and it led maybe a stone’s easy toss to another whitewashed wall that contained the driveway. Where they intersected, there was a little fake watchtower, with empty windows and a tile roof with upturned corners.

Beyond that wall were the tops of evergreens and other, barren, trees. A woods.

Safety, one might think.

But he had read a lot. And he had talked with Banichi and Jago on the long voyage.

And Banichi had told him once, “The best place to put a trap is where it seems like the way out.”

Too attractive, a woods running right up to the house walls.

“The woods is going to be guarded,” he whispered. “Look for an alarm on the gate.”

“Yes,” Antaro said, and rolled half over so she could look up at the gate. She did that for some little time, and then pointed to the base of the gate and made the sign for “alarm.”

He looked for one. He could not see it, but when he looked closely, he saw a little square thing.

“Over,” she signed to him. And “Come.”

He moved closer. Antaro signaled for Jegari to come close, and he crawled close. Antaro stepped onto her brother’s back, and he braced himself, and she took hold of the top of the gate and just– it was amazing—lifted herself into something like a handstand. She went over, and lit ever so lightly.

She waited there, and Jegari offered his hands and whispered, “Go, nandi.”

He did, as best he could. He climbed up onto Jegari’s hands, and Jegari lifted him up to the top of the gate. Antaro stood close, so he could get onto her shoulders, and then she knelt down and let him gently to the ground, turning then to offer her hands to Jegari, who had pulled himself up and climbed atop the gate. Jegari was a heavy weight—but she braced herself and made a sling of her hands and he got down.

They were over. They were clear.

But they were also insidean alarmed area. It was a very bare, very exposed corner of a small winter-bare orchard—walled about with the same house-high barrier, with those intermittent little watchtowers. The old trees were just leafing out, not a lot of cover. And the orchard ran clear back out of sight, beyond the house, and evidently the wall went on, too, just a few towers sticking up above the slight hill. Probably it enclosed the whole estate grounds.

But something interesting showed, nearest, at the base of that corner tower: steps. One could go up there. Cajeiri pointed at it, pointed at a second tower, somewhat less conspicuous, beyond the gray-brown haze of winter branches. Pointed at the shuttered great windows in this face of the house.

Jegari nodded grim agreement. That little tower—that might be somewhere they would not look.

Antaro nodded, and moved out. Cajeiri followed, trying to move without scuffing up the leaves; and Jegari came after him. They reached a sort of flagstone patio that probably afforded very pleasant evenings in summer, with the trees in leaf. Tools stood there against the wall, rusting in the winter rains. Mani would never approve.

They trod carefully on that little patio, with its dead potted plants, its pale flagstones, and its upward stairs. And Cajeiri started to take that stairs upward to that whitewashed wall and tower, but Antaro pressed him back and insisted on going up first.

There was a chain up there, blocking off the top. She slipped under it, and slithered up onto the walk and into the tower, then slithered back again, signaling “Come quickly.”

Cajeiri climbed the steps as fast as he could, with Jegari behind him, up, likewise slithered under the prohibiting chain, crawled onto a little concrete walkway along the fake, whitewashed battlement. A very undersized door went into the tower from there, slithering was the only way in. Glassless windows lit the inside—and a very modern installation, a kind of box with a turning gear.

Cajeiri’s heart went thump. They had come on the very sort of surveillance they were afraid of. But the sensor was aimed out the windows: it shifted from one window to the other, whirr-click, left to right, right to left, watching out in the woods. Towers like this one were all along the wall– there were several in view just from the orchard, and probably every single tower had something similar inside. But the machinery was all dusty and rusty, even if it was working. There were big cracks in the wall, starting from two of the windows, the outermost and the innermost cracks which nobody had fixed. It was not the best maintenance that kept this system.

On their knees, peering through the crack beneath the garden-side window, they had a good view of the house from here, and a lot more of the orchard. They could see where the portico had collapsed in front.

Worse—much worse, there was somebody in Guild black just coming over the house roof.

They all dropped down, and Cajeiri kept his eye to the crack.

“Guild!” he whispered, with a chill going through him. There was an enemy, they were still hunting for them, and in a little while, as he watched through that crack, two more Guildsmen came around the corner of the house. They opened the alarmed gate, and shut it, and started methodically looking through the orchard.

Cajeiri knelt there, watching the search go on, watching that solitary black presence on the roof, out of sight of those below, and he shivered a twitch or two, which embarrassed him greatly.

Not good. Not good at all. Nand’ Bren was going to come back, and there was a trap, and they were already in it. These people, however, were standing around and pointing, more than searching. Pointing at the roof, and pointing at the front gate.

One could almost imagine them laying plans for exactly such a thing as an attack from Bren’s estate. They were devising traps.

They might come up here to check the security installation.