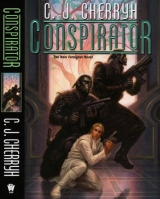

Текст книги "Conspirator"

Автор книги: C. J. Cherryh

Жанр:

Научная фантастика

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

But mani had taught him how to release his face from his unhappiness. One could be as angry as it was possible to be, and completely relax the face, even smilec he knew how to add that little touch, without giving away anything. He could do it with his father and his mother. But he did not try it with Great-grandmother, foreseeing a thwack to the ear—she was only as tall as he was, but she could manage it, being able, he had once thought, to read his mind. Not the case, of course: that was for the human dramas nand’ Bren had lent him; but read his actions, oh, indeed she did that, better than anyone.

So they walked in to dinner together, and he kept his self-control. He was gracious to mani, to his mother, and to his father. He tested his self-control—and the situation—by saying, conversationally, “One had very much hoped that mani would take up residence again. There is surely room enough.” He darkly suspected that his father might have discouraged Great-grandmother from staying. He knew that propriety would be strained to the limits andhis father would have been held up to blame had Great-grandmother taken up residency down the hall, with Uncle Tatiseigic so he said it the polite way, and was unrewarded. His father said:

“She wished otherwise, did you not, esteemed grandmother?”

“We have affairs to tend in the East,” mani said.

“But I might go there!” he said, his control slipping just for a moment. He added, mildly, “If my father and honored mother could spare me from lessons only for a month or so.” Surelyhis parents’ apartment, promised to be ready before now, would be ready by thenc and mani could come back with him to She-jidan and everything would be better.

“One regrets to disappoint,” his father said without a shred of remorse, and said, directly to Great-grandmother: “He has frustrated three tutors and driven one into retirement.”

“Honored father,” Cajeiri protested. “You said yourself—”

“That the man was a fool? An excellent numbers man. A fool. But despise the numbers as you may, my enlightened and too modern son, you still need to know them.”

“Why?” mani shot at him, at him, not his father, and he answered, meekly,

“Because ’counters have political power and superstitious people are very excitable, mani, so one should knowthe numbers of a situation to know what superstitious people will believe.”

His father laughed. “There, grandmother, you have produced a cynic.”

“Next year,” Cajeiri said, doggedly being what Great-grandmother would call pert, “I shall be a more fortunate number in agec” He was infelicitous eight, divisible by unfortunate four, each bisected by unhappy two. “And then perhaps people will hear me seriously.”

“You have been fortunate,” his father said, “to be alive, young gentleman.”

“Fortunate to sit at this table,” his mother said. “Wheedling is not becoming anywhere.”

“Forgive me, honored mother. It was excessive.” Decidedly, it had been. He had gone much too far. He sighed, hating his own impulsiveness, and helped himself to more sauce for the meat course, fighting to cool the temper that had roused up. Great-grandmother assured him he had inherited that temper from Great-grandfather, and his grandfather, and his father. “Find myinheritance in you!” she had repeatedly instructed him. “Mountain air is chill. It stimulates the wit, young man. Choleronly ruins one’s digestion.”

It was good advice. He had been in Great-grandmother’s mountains. He had been in the snow. He understood. And like nand’ Bren’s rock, paper, scissors—he had seen how wit beat choler, every time.

So he reined in his anger, ate his dinner, and while mani and his mother and father chatted about the weather, the hunting, the repairs to the apartment—he thought.

He thought about nand’ Bren having to leave.

He thought about Uncle Tatiseigi being right down the hall and having his guards right outside his door, and Uncle Tatiseigi calling on his father every time he did a thing out of the routine.

He thought about all these things, and the whole situation was what mani called—intolerable.

Nand’ Bren had promised to take him on his boat when things settled down and people stopped shooting at each other, and it had been quiet for months, had it not?

His parents were convinced he was a fool, untrustworthy even if he should go to Taiben, where Antaro’s and Jegari’s parents and the lord of the Taibeni (who was a relation) would take extraordinary care of him. He saved that hope for absolute last.

He had asked to have his own staff and his own apartment, even if it let out into theirs, but he knew what modifications they were making to his parents’ old domicile, and there was noprovision for him in that place having anything but a foyer, a closet of a study, and a small bedroom of his own, not even his own bath—they said another bath was impossible without tapping into the lines next door, which were in Bren’s proper apartment, which was being occupied by the Farai, and noone lately offended the Farai, not even for Lord Bren’s sake. And it was a security risk. They were building a monitoring station against that wall, which he was not supposed to say.

But it was all just disgusting.

Still, he kept a pleasant face, and had his dinner, and said a proper good-bye to mani, and a good night to his father and his mother, leaving the adults to their brandy. He gathered up Antaro and Jegari and the two guards who were Uncle Tatiseigi’s and went back to his quarters.

He said, to the guards, “You should have your supper now. Go. I shall have an early night. You might have some brandy, too.”

“Nandi,” they said, and went off, unsuspecting and cheerful in the suggestion. They were not nearly as bright as his father’s guards.

Antaro and Jegari followed him inside and looked worried. They wereas bright as anybody could ask.

And he walked over to his closet and took out his rougher clothes, and laid them on the bed. He knew the handsigns the Guild used. He used several of them to say, “downstairs,” and “all of us,” and “going.”

“Where?” Antaro signed back, in some distress.

“Nand’ Bren,” was a sign they had, the same that Bren’s own guard used.

“Your parents,” came back at him.

He gave them that tranquil, pleasant look he had practiced so hard. And laid his fist over his heart, which was to say, “Carry out orders.”

They didn’t say a thing. They went to their nook and into their separate rooms and brought back changes of clothing. They weren’t Guild. They had no weapons, nor anything like the communications the Guild had. They just quietly packed things in a single duffle, and meanwhile Cajeiri opened his savings-box, emptied that, found a few mangled ribbons of the Ajuri colors, his mother’s clan, and the green of the Taibeni, and, yes, finally, a somewhat dog-eared train schedule book he had gotten from his father’s office.

He opened that and found that, yes, a train did leave the Bujavid station in the night: it went down to the freight depot, probably to pick up supplies, which was exactly the thing. Cook would be cleaning up in the kitchen, and the major domo would be engaged with mani—Cook was hers, more than his parents’, and that conversation would take a little time. The whole house would be focused on mani, because most everyone was hers, except his father’s and his mother’s staff, and those few would be paying attention to his father and mother, because everyone else would be waiting on mani and making sure she had all she wanted.

Mani probably would socialize late—for her—turn in, and catch several hours’ sound sleep before she got up to go to the airport.

Perfect.

Chapter 4

« ^ »

Brandy, in the sitting room, with the comfortable wood fire, the rustic stone hearthc beneath ancient beams. The furniture looked a little out of place, being ornate and carved and far from rustic in its needlepoint seats and backs. The carpet was straight from the Bujavid: it gave the place, to Bren’s eye, a sort of a piratical air, the furnishings all having been smuggled off to the coast during the city riots and none of the furniture quite matching.

But, formal or not, they were comforting, like old friends, every stick of the furnishings, the priceless porcelain vases on their pedestals. Bren was delighted with everything the staff had done, and expressed as much to the staff who served there. “One is astonished,” he said. “One knew you had extraordinary daring to make off with the dining room carpet, nadiin, but however did you get the furniture here?”

“In a truck, nandi,” was the answer. “In several trucks. We pretended to loot it, we hid it in Matruso’s cousin’s house, and we took it by back roads.”

“Extraordinary,” was all he could find to say. “One is extremely grateful, nadiin-ji. Say so to all the staff—and to Matruso’s cousin!”

“Shall we serve, nandi?”

“To be sure,” he said. Banichi and Jago were still with him, standing, and didn’t meet his eyes, which indicated they weren’t looking for a signal to sit down, and didn’t in the least want one.

Barb and Toby were also standing, on best behavior—finally. “Sit down, sit down, Barb, Toby. We’re all informal here, after dinner. Any chair you like.”

They were all outsized chairs for a human frame—Toby’s feet reached the floor, Barb’s didn’t, so she crossed her ankles and swung them a moment, feeling over the carved wood with pink-lacquered fingernails.

“Very fancy,” Barb said.

“ This,” Bren said, slowly taking his own favored chair, “is the spoils of my Bujavid apartment. My staff risked their necks getting it away—or God knows what would have happened to it. Carted off to the South, likeliest. They shot up the aiji’s apartments, killed poor old Eidi, broke things—you have to understand, it’s like breaking things in a museum. These things are national treasures. The finest of the finest.”

“They don’t have museums, do they?” Toby asked. Most every city on Mospheira did have.

“Not as such,” he said, “but people do tour historic places, and the great houses do rotate pieces downstairs, into the public areas, during their own tour season. Anybody can go to the Bujavid, on the lower levels; anybody can apply to visit the library and the collections. Anyone with scholarly interest can apply to have certain articles moved into a viewing room. You just don’t fire off guns in a place like that. It shocked everyone, it created great public resentment, once that fact got out. It was one thing that Murini’s lot shot people; it was another that his fools ripped up pieces of the past. You can’t imagine the furor.”

“Well, I’d think people were more valuable,” Barb said.

“People are valuable to their clan. The past is valuable to everybody. Losing that—is losing part of the collective. Part of the social fabric. It ripped. But restorers and copyists are at work. That’s one thing that’s taken so long. The aiji’s carpet that was ruined—the fools set a fire, for God’s sake—that’s going to take years to restore. In the meanwhile there will be a copy. The restored piece will probably go down to a formal room in the lower Bujavid.”

“The repairs will be part of its history, I suppose,” Toby said.

He was pleased. Sometimes Toby did get things. “Very much so. Exactly.”

The brandy came, sizable doses, delivered by staff on a silver tray.

“Quite the life,” Toby said, and shifted an uneasy glance toward Banichi and Jago, who hadn’t moved, not an inch. Toby didn’t say anything. But the thought was plainc Can’t they sit?

“A good life,” Bren said, ignoring the issue. He had no apology for the staff’s formality, no protest about anything staff wanted to do. They were on edge, in foreign presence, touchy about his dignity, which they saw as offended. But he was very content at the moment, with a smoky brandy, a warm fire, and his brother at hand. He did relax.

“You have to wear that all the time?”

“The vest?” He did. He’d shed the dinner coat, and sat quite informally in this family setting, though staff had offered to bring him an evening jacket. Putting one on would be a struggle with the lace, and he’d opted not to bother. “This, I assure you, is informal.”

“The shirt,” Toby said. “The whole outfit. I have a spare sweater, pair of pants that would fit you.”

He shook his head, gave a little laugh. “I really couldn’t. The staff is on their best behavior. Guests, you know. They would be a little hurt if I didn’t look the way they like.”

“Well, I suppose we look a little shabby,” Toby said.

“I could find youa shirt and coat,” he said. “Boots, now, boots are always at a premium.”

Toby laughed uneasily and laid a hand on his middle. “I wouldn’t look that good in a cutaway, I’m afraid.”

“I’d like to try what the women wear,” Barb said.

That was a poser. “None in my wardrobe, I’m afraid.”

“Oh, but there’s staff,” Barb said.

“I can’t quite,” Bren said. “And it wouldn’t fit you.” He couldn’t envision going to one of the servants and asking to borrow herwardrobe—not to mention the issues of rank and guest status and Barb’s already shaky standing with staff. “Best not ask. Next time, next time you visit, I’ll send you both a package, country court regalia, the whole thing.”

“Not me, in the lace,” Toby said. “I’d have that in the soup.” And then he added: “You used to wear casuals here.”

“A long time ago. Different occasion.” Silence hung in the air a moment.

“A few years,” Toby said. “Not that long ago.”

“It’s different,” he said. “It’s just different now.”

“You’re Lord Bren, now. Is that more than being the paidhi?”

“A bit more.”

“When are you going to visit Mospheira?”

“It’s what I said. It’s not likely I will,” he said into a deeper and deeper silence. “Not that I wouldn’t enjoy certain places. Certain people. But it’s just different.”

And the silence just lay there a moment. “You can’t say ‘enjoy old friends,’ can you?”

“Toby,” Barb said, a caution.

Which said, didn’t it, that he’d been the subject of at least one unhappy conversation?

“I’m kind of out of the habit,” he said. “And no, not the way I think of ‘friends.’ Nobody on the island’s in that category any longer. Shawn Tyers, maybe. But he’s busy being President. Sonja Podesta. Sandra Johnson. Who’s gone on to have a life.” He’d named two women and he saw Barb frown. “I have friends up on the station. Jase, for one. Jase is a goodfriend. But—” That was headed down its own dark alley. He stopped, before it got to its destination, which was that it wasn’t easy to keep friendships polished when he was more likely to get back to the station sooner than Jase would get a chance to visit the planet. And that wasn’t going to be any time soon. “On the continent I have my associates,” he said. “My aishi.”

Toby didn’t look happy with that statement, but damnedif Toby was going to sit there in front of Banichi and Jago, who did understand Mosphei’, and tell him that atevi sentiments were in some measure deficient for a human.

“Trust me,” Bren said, pointedly, “that I’m extremely content in my household. I’m not alone. I’m never alone, not for an hour out of the day. And I do ask you both to understand that, in all possible ways.”

Again the small silence.

“ Ibrought you a present,” Toby exclaimed suddenly, getting up, shattering the dark mood entirely. “I have it in our room.”

“Let Banichi go with you,” Bren said gently, and with a little restoration of humor. “ Youdon’t run about alone, either. You come here with no bodyguard, unless Barb wants to take that postc you can’t just run up and down the halls as if you were my staff. You’re a guest. You need an escort. You don’t open your own doors. It’s my social obligation.”

Toby looked at him as if he were sure he was being gigged, but he stayed quite sober.

“I’m serious. It’s just good manners. Mine, not yours, but be patient.”

“So who’s going to escortc Barb?” Toby asked, and slid a glance toward Jago, the only woman in his personal guard– Jago, who had as soon consign Barb to the bay.

“Exactly,” Bren said, and in Ragi: “Banichi-ji, please see Toby to his room. He forgot an item.”

“Nandi,” Banichi said gravely, and went to the hall door and opened it for Toby.

Which left him, and Barb, and Jago standing by the door.

“So,” Barb said in the ensuing silence, “you arehappy, Bren.”

“Very,” he said. “You?”

“Very,” she said, and slid in the chair and stood up, walking over to the fire, which played nicely on her fair curls. She bent down and put a stick of wood in. “I love fires. Not something you do on board.”

He sat where he was. “Not likely. You live aboard the boat, year round?”

She nodded, and looked back at him, and walked back toward her chair.

Or toward him. She rested a hip on the outsized arm of his chair. He didn’t make his arm convenient to her. She laid a hand on his shoulder.

“She wouldn’t object, would she?”

“She may, and I do. Move off, Barb.”

“Bren, I’m your sister-in-law. Well, sort of.”

“ Marryhim, then.” He wished he hadn’t said that. He couldn’t get up without shoving Barb off the arm and he could all but feel Jago’s eyes burning a hole in Barb. “It’s not funny, Barb.”

“I just don’t see why—”

He put his hand on her to shove her off the chair arm, just as the door opened and Toby walked in.

And stopped.

Barb got up sedately. Cool as ice. In that moment he hated her, and he hated very, very few people on either side of the straits.

Toby didn’t say a thing. And there wasn’t a graceful thing for him to say.

“I was just talking to Bren,” Barb said.

“Why don’t you turn in?” Toby asked. “Bren and I have things to discuss.”

Barb’s glance flicked toward Jago, and the ice crackled. Barb shook her head emphatically at that suggestion. “I’ll walk back when you do,” she said. “Toby, honestly, we were just talking. I wanted to ask Bren something. His guard understandsus.”

“It was talk,” Bren said. The Mospheiran thing to do was to explode. Among atevi, involving atevi, it cost too much. So did having it out now, on the very first night of their stay. “What is this surprise of yours?”

A wrapped present. Gilt paper. Ribbons. Toby resolutely held it out to him, a box about the size of a small book, and Bren got up and took it. Shook it, whimsically. Toby gave him a suspicious look.

“We’re too old for that, are we?” Bren said. “Well.” He looked at the paper. It said Happy Birthday. “God, how long have you saved this one?”

“Since the first year you went away,” Toby said. And shrugged. “It can’t live up to expectations. But I was dead set you were coming back. So I got it, for luck.”

“Superstitious idiot,” Bren said, and, it being Jago and Banichi alone, he took the chance to hug Toby, hug him close and mutter into his ear. “Barb’s mad at me. She made that damned clear. Don’t react. It’ll blow over.”

Toby shoved him back and looked at him at close range. Didn’t say a word.

“Truth,” he said, steady on with the gaze, and Toby scowled back.

“Truth?” Toby asked him, when that wasn’t exactly what Toby was asking, and he grabbed Toby and pulled him close for a second word.

“ Mylady’s standing over there armed to the teeth, and she doesn’t take jokes. Neither does Banichi. For God’s sake, Toby, nothing’s at issue. Barb’s acting out; she’s mad about dinner. I embarrassed her. Youknow Barb by now.”

He took a big chance with that, a really big chance. But this time when Toby shoved him back at arm’s length to look at him, Toby had a sober, unhappy look on his face.

“Damn it,” Toby said.

“Look, you two,” Barb said. She stood, arms folded, over to the side. “What’s going on between you two?”

“Turn about,” Bren said darkly, and held up the present. “Shall I open it?”

“Open it,” Toby said. “It’s not much.”

“Oh, we’ll see,” he said, and carefully edged the ribbon off, and unstuck the paper.

“He’s one of those,” Barb said. “He never will tear the paper.”

“Waste not, want not,” he said.

“He reuses it, too,” Toby said. “Come on, Bren. Just rip it.”

He reached the box, carefully, ever so carefully folded the paper and laid it on the mantel with the ribbon. Then he opened the box.

A pin, of all things, an atevi-style stickpin. Gold, with three what-might-be diamonds.

He was astonished.

“Where on earth?” he asked.

“Well,” Toby said, “I had it made. Is it proper? Kabiu? I asked the linguistics department at the University.”

“The paidhi’s color,” he said. “It counts as white. Kabiu, right down to the numbers. Now what am I going to do to get back at you on yourbirthday?”

“I got my present,” Toby said. “I got my brother back.”

“You did,” he said, and gave Toby another hug, and offered– not without the hindbrain in action—his other arm to Barb, and hugged them both. “Fortunate three. Two’s unlucky. Has to be three.”

He didn’t know how Barb liked that remark, but it was fair enough, and Toby duly hugged him back, and Barb did, and he hoped Jago didn’t throw him out of bed that night.

“All right,” he said, disengaging, “that’s a thorough quota of family hugs for the next couple of weeks. I’ll see you off to sea in good style, but we’ve got to be proper in the staff’s eyes in the meanwhile. Banichi and Jago understand us, but the staff, I assure you, would be aghast, and trying to parse it all in very strange ways. I’m going to wear this pin tomorrow. I’ll wear it in court. I could still get you a lace shirt, brother.”

“No. If Barb can’t, I won’t,” Toby said, his arm around Barb at the moment.

“Probably best,” he said. He felt better as he went back to his chair, sat down, and took up his brandy. They did the same, chairs near each other. Peace was restored, despite Barb’s best efforts to the contrary.

And maybe—maybe he’d actually won a lasting truce and settled something.

“So where did you come in from?” he asked Toby conversationally, and listened comfortably and sipped his brandy– pleasant to hear someone else’s adventures instead of having them, the thought came to him. They’d been worried sick about Toby at one point, after Tabini’s return to the Bujavid, but he’d turned up, out at sea, doing clandestine things for the human government over on Mospheira, part of a communications network, for one thing, and probably that boat out there still had some of that gear aboard.

His own had a few nonregulation things aboard, too—or had had, before he’d left for space. That was the world they lived in, occasionally dangerous. He hoped for it to stay calm for a few years.

He was abed before Jago came in. Abed, but not asleep: he kept rehearsing the dinner, the business with Barb. He lay in his own comfortable bed, between his own fine sheets, and stared at the ceiling, until Jago was there to improve the view. She stripped out of the last of her uniform and stood there, dark against the faint night light. Rain spattered the windows, rain with a vengeance, hitting the glass in sharp gusts of wind.

“One greatly regrets,” he said to that silhouette, unable to read her, but reading the hesitation. “One ever so greatly regrets that unpleasantness this evening, Jago-ji. Barb is, unfortunately, Barb.”

“Her man’chi is to you,” Jago said, her voice carefully without inflection. “One understands. She places you in a difficult situation. Am I mistaken in this?”

Oddly enough, the atevi view of things said it fairly well. “You are not mistaken,” he said. “Very like man’chi. She gravitates to me every time she gets the least chance. But there is anger in it, deep anger. I offended her pride.”

“Would it mend matters to sleep with her?” Jago asked.

“Far from it. It would encourage her and make my brother angry. And I feel nothing but anger toward her. Come to bed, Jago-ji.”

Jago did settle in, to his relief. Her skin, ordinarily fever warm, was slightly cool, and he rubbed her arm and her shoulder to warm it.

“I might speak to her,” Jago said. “Reasonably.”

“I shall hold that in reserve,” he said. “I think I may have to speak to my brother if this goes on. If she causes him griefc”

“It seems likely she will,” Jago said.

“Very likely,” he said, and sighed. “Barb has good qualities– at best advantage when I appear nowhere on her horizon. Her man’chi, given, is very solidc”

“Except to your brother,” Jago said.

“Except when I appear,” he said.

“Conflicted man’chi,” Jago said. “The essence of every machimi.”

The dramatic heritage of atevi culture. Plays noted for the quantity of bloodshed.

“Let us try not to have any last act,” he said with a sigh. “Not on this vacation.”

Jago laughed, soft movement under his hand.

And slid her arm under his ribs, around him, a sinuous, fluid embrace that proved the chill had not gotten inside—a force and slight recklessness that advised him Jago was in a mood to chase Barb right out of the bedroom, in no uncertain terms.

Reckless to a fine edge of what was pleasure, but never over it—and deserving of a man with his mind on her, nowhere else in the universe.

He committed himself, with that sense of danger they hadn’t had in bed in, oh, the better part of a year. The storm outside rumbled and cracked with thunder, making the walls shake, and they came together with absolute knowledge of each other—not quietly, nor discreetly, nor even quite safelyc but very, very satisfyingly.

Chapter 5

« ^ »

He slept. Really slept. And in the morning he had a leisurely breakfast—Toby and Barb slept in, but he and Jago were up with the sun, and being joined in the dining room by Banichi, and Tano and Algini, they all five had a very ample country breakfast, absolutely devouring everything on the plates.

“You should consider this your vacation, too, nadiin-ji,” he said to his staff over tea. “Arrange to fish, to walk in the garden, to do whatever you like as long as we are here. No place could be safer. I have my office work to do. My brother and his lady will be engaged with me when they finally do wake. I promise not to let them free to harass the staff.”

There was quiet laughter, even from Jago, who frowned whenever Barb’s name came into question. But Banichi proposed they should go down to the shore and inspect the boat, and see how it was, and Bren said they should do it by turns, because he very well knew that his bodyguard wouldn’t consider all going at once.

“Manage to take a fishing pole or two,” he said to them. “Catch us our supper, why don’t you?”

“And shall you be in your office all day?”

“Oh, I foresee walking in the garden with our guests, or maybe down to the shore, or sharing tea in the sitting room. Nothing too strenuous.” In fact, he had some sore spots from last night, and regretted not a one of them. “Just amuse yourselves. I shall assign two servants to the hall, to forestall you having to escort either of them. Just relax. Trust even me to find my way, nadiin-ji. I shall just be going between bedroom, dining hall, and my study.”

He sent them off with a gentle laughc sure that, since Banichi and Jago were going to the shore, Tano and Algini were going to be close about, probably finding a place to sit and work on things that interested themc and still within call, supposing there should be some sort of emergency. They never quite relaxed. But he tried to encourage it.

He had, first on the agenda, a meeting with the major domo, Ramaso, who brought the household accounts, all balanced and impeccably writtenc the old man never had taken to the computer, but the accounts were simple. The village and the household both sold fish, they bought food and medicines and items for repair, clothing and rope and tackle, they had shipped a boy with a broken arm and a pregnant woman down the coast to medical care, which the estate had paid for, as it bore all such expenses for the village.

All the history of the past months was written in that arithmetic, and told him that the place had prospered, and made do, even during Murini’s regime. They sold to neighboring districts, they shipped an increasing amount to Shejidan, recovering the trade they had once enjoyed before the coup, and they maintained a good balance in the accounts.

“Very well done,” he said to Ramaso. “Come, nadi-ji, call for tea, sit with me, and tell me all the gossip of the district.”

The old man was pleased, and a man brought the tea in an antique and very familiar service with a mountain scene on the teapotc there was no end to the things his enterprising staff had smuggled out of Shejidan during the collapse.

“Extraordinary,” Bren said. “I greatly enjoy that tea set.”

“The staff is pleased, nandi.” A sip of tea. “Please visit the storeroom. The moment the irregularities are worked out in the capital, you will have the great majority of your furnishings returned. The Farai got very little of historic value.”

He had not been inside that apartment since his return. He had understood the staff had gotten a great deal of his property away, but now that he had reached Najida, there were surprises at every turn, items forgotten and rediscovered. “One is very pleased, very pleased, nadi-ji. Not least to see the faces of staff. One has not forgotten.”

“I shall relay that, nandi.”

“Thank them, too, for their understanding regarding my brother’s companion last night. Her customs are informally Mospheiran. She has no education in the manners of an atevi house. Such actions would rouse no great stir on the island– they are not entirely appropriate to formal occasions, to be quite frank, but they are not, there, scandalous, nor did she understand the nature of the dinner.”

Atevi didn’t blush, outstandingly, but it was possible that the old man did. At very least he found momentary contemplative interest in a sip of tea. “Indeed, nandi, one will so advise the staff.”

“One earnestly hopes to forestall another such event,” Bren said. “And one apologizes to the staff. My brother and the lady will guest here—perhaps two weeks, certainly no longer. Kindly station staff in the main hall to see to their comings and goings. During part of that time, I hardly dare wonder if I might leave them here unattended for a day. One is urgently obliged to pay a visit to the neighbors.”

That was to say, Lord Geigi’s estate, their nearest neighbor– whose regional influence had likely saved the paidhi-aiji’s residence during the Troubles, or he might not be sitting sipping tea in this sitting room now.