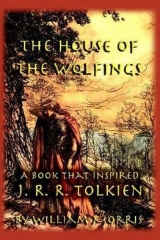

Текст книги "The House of the Wolfings"

Автор книги: William Morris

Жанры:

Историческое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

“O house of the heart of the mighty, O breast of the battle-lord

Why art thou coldly hidden from the flickering flame of the sword?

I know thee not, nor see thee; thou art as the fells afar

Where the Fathers have their dwelling, and the halls of Godhome are:

The wind blows wild betwixt us, and the cloud-rack flies along,

And high aloft enfoldeth the dwelling of the strong;

They are, as of old they have been, but their hearths flame not for me;

And the kindness of their feast-halls mine eyes shall never see.”

Thiodolf’s lips still smiled on the old man, but a shadow had come over his eyes and his brow; and the chief of the Daylings and their mighty guests stood by listening intently with the knit brows of anxious men; nor did any speak till the ancient man again betook him to words:

“I came to the house of the foeman when hunger made me a fool;

And the foeman said, ‘Thou art weary, lo, set thy foot on the stool;’

And I stretched out my feet,—and was shackled: and he spake with a dastard’s smile,

‘O guest, thine hands are heavy; now rest them for a while!’

So I stretched out my hands, and the hand-gyves lay cold on either wrist:

And the wood of the wolf had been better than that feast-hall, had I wist

That this was the ancient pit-fall, and the long expected trap,

And that now for my heart’s desire I had sold the world’s goodhap.”

Therewith the ancient man turned slowly away from Thiodolf, and departed sadly to his own place. Thiodolf changed countenance but little, albeit those about him looked strangely on him, as though if they durst they would ask him what these words might be, and if he from his hidden knowledge might fit a meaning to them. For to many there was a word of warning in them, and to some an evil omen of the days soon to be; and scarce anyone heard those words but he had a misgiving in his heart, for the ancient man was known to be foreseeing, and wild and strange his words seemed to them.

But Agni would make light of it, and he said: “Asmund the Old is of good will, and wise he is; but he hath great longings for the deeds of men, when he hath tidings of battle; for a great warrior and a red-hand hewer he hath been in times past; he loves the Kindred, and deems it ill if he may not fare afield with them; for the thought of dying in the straw is hateful to him.”

“Yea,” said another, “and moreover he hath seen sons whom he loved slain in battle; and when he seeth a warrior in his prime he becometh dear to him, and he feareth for him.”

“Yet,” said a third, “Asmund is foreseeing; and may be, Thiodolf, thou wilt wot of the drift of these words, and tell us thereof.”

But Thiodolf spake nought of the matter, though in his heart he pondered it.

So the guests were led to table, and the feast began, within the hall and without it, and wide about the plain; and the Dayling maidens went in bands trimly decked out throughout all the host and served the warriors with meat and drink, and sang the overword to their lays, and smote the harp, and drew the bow over the fiddle till it laughed and wailed and chuckled, and were blithe and merry with all, and great was the glee on the eve of battle. And if Thiodolf’s heart were overcast, his face showed it not, but he passed from hall to wain-burg and from wain-burg to hall again blithe and joyous with all men. And thereby he raised the hearts of men, and they deemed it good that they had gotten such a War-duke, meet to uphold all hearts of men both at the feast and in the fray.

CHAPTER X—THAT CARLINE COMETH TO THE ROOF OF THE WOLFINGS

Now it was three days after this that the women were gathering to the Women’s-Chamber of the Roof of the Wolfings a little before the afternoon changes into evening. The hearts of most were somewhat heavy, for the doubt wherewith they had watched the departure of the fighting-men still hung about them; nor had they any tidings from the host (nor was it like that they should have). And as they were somewhat down-hearted, so it seemed by the aspect of all things that afternoon. It was not yet the evening, as is aforesaid, but the day was worn and worsened, and all things looked weary. The sky was a little clouded, but not much; yet was it murky down in the south-east, and there was a threat of storm in it, and in the air close round each man’s head, and in the very waving of the leafy boughs. There was by this time little doing in field and fold (for the kine were milked), and the women were coming up from the acres and the meadow and over the open ground anigh the Roof; there was the grass worn and dusty, and the women that trod it, their feet were tanned and worn, and dusty also; skin-dry and weary they looked, with the sweat dried upon them; their girt-up gowns grey and lightless, their half-unbound hair blowing about them in the dry wind, which had in it no morning freshness, and no evening coolness.

It was a time when toil was well-nigh done, but had left its aching behind it; a time for folk to sleep and forget for a little while, till the low sun should make it evening, and make all things fair with his level rays; no time for anxious thoughts concerning deeds doing, wherein the anxious ones could do nought to help. Yet such thoughts those stay-at-homes needs must have in the hour of their toil scarce over, their rest and mirth not begun.

Slowly one by one the women went in by the Women’s-door, and the Hall-Sun sat on a stone hard by, and watched them as they passed; and she looked keenly at all persons and all things. She had been working in the acres, and her hand was yet on the hoe she had been using, and but for her face her body was as of one resting after toil: her dark blue gown was ungirded, her dark hair loose and floating, the flowers that had wreathed it, now faded, lying strewn upon the grass before her: her feet bare for coolness’ sake, her left hand lying loose and open upon her knee.

Yet though her body otherwise looked thus listless, in her face was no listlessness, nor rest: her eyes were alert and clear, shining like two stars in the heavens of dawn-tide; her lips were set close, her brow knit, as of one striving to shape thoughts hard to understand into words that all might understand.

So she sat noting all things, as woman by woman went past her into the hall, till at last she slowly rose to her feet; for there came two young women leading between them that same old carline with whom she had talked on the Hill-of-Speech. She looked on the carline steadfastly, but gave no token of knowing her; but the ancient woman spoke when she came near to the Hall-Sun, and old as her semblance was, yet did her speech sound sweet to the Hall-Sun, and indeed to all those that heard it and she said:

“May we be here to-night, O Hall-Sun, thou lovely Seeress of the mighty Wolfings? may a wandering woman sit amongst you and eat the meat of the Wolfings?”

Then spake the Hall-Sun in a sweet measured voice: “Surely mother: all men who bring peace with them are welcome guests to the Wolfings: nor will any ask thine errand, but we will let thy tidings flow from thee as thou wilt. This is the custom of the kindred, and no word of mine own; I speak to thee because thou hast spoken to me, but I have no authority here, being myself but an alien. Albeit I serve the House of the Wolfings, and I love it as the hound loveth his master who feedeth him, and his master’s children who play with him. Enter, mother, and be glad of heart, and put away care from thee.”

Then the old woman drew nigher to her and sat down in the dust at her feet, for she was now sitting down again, and took her hand and kissed it and fondled it, and seemed loth to leave handling the beauty of the Hall-Sun; but she looked kindly on the carline, and smiled on her, and leaned down to her, and kissed her mouth, and said:

“Damsels, take care of this poor woman, and make her good cheer; for she is wise of wit, and a friend of the Wolfings; and I have seen her before, and spoken with her; and she loveth us. But as for me I must needs be alone in the meads for a while; and it may be that when I come to you again, I shall have a word to tell you.”

Now indeed it was in a manner true that the Hall-Sun had no authority in the Wolfing House; yet was she so well beloved for her wisdom and beauty and her sweet speech, that all hastened to do her will in small matters and in great, and now as they looked at her after the old woman had caressed her, it seemed to them that her fairness grew under their eyes, and that they had never seen her so fair; and the sight of her seemed so good to them, that the outworn day and its weariness changed to them, and it grew as pleasant as the first hours of the sunlight, when men arise happy from their rest, and look on the day that lieth hopeful before them with all its deeds to be.

So they grew merry, and they led the carline into the Hall with them, and set her down in the Women’s-Chamber, and washed her feet, and gave her meat and drink, and bade her rest and think of nothing troublous, and in all wise made her good cheer; and she was merry with them, and praised their fairness and their deftness, and asked them many questions about their weaving and spinning and carding; (howbeit the looms were idle as then because it was midsummer, and the men gone to the war). And this they deemed strange, as it seemed to them that all women should know of such things; but they thought it was a token that she came from far away.

But afterwards she sat among them, and told them pleasant tales of past times and far countries, and was blithe to them and they to her and the time wore on toward nightfall in the Women’s-Chamber.

CHAPTER XI—THE HALL-SUN SPEAKETH

But for the Hall-Sun; she sat long on that stone by the Women’s-door; but when the evening was now come, she arose and went down through the cornfields and into the meadow, and wandered away as her feet took her.

Night was falling by then she reached that pool of Mirkwood-water, whose eddies she knew so well. There she let the water cover her in the deep stream, and she floated down and sported with the ripples where the river left that deep to race over the shallows; and the moon was casting shadows by then she came up the bank again by the shallow end bearing in her arms a bundle of the blue-flowering mouse-ear. Then she clad herself at once, and went straight as one with a set purpose toward the Great Roof, and entered by the Man’s-door; and there were few men within and they but old and heavy with the burden of years and the coming of night-tide; but they wondered and looked to each other and nodded their heads as she passed them by, as men who would say, There is something toward.

So she went to her sleeping-place, and did on fresh raiment, and came forth presently clad in white and shod with gold and having her hair wreathed about with the herb of wonder, the blue-flowering mouse-ear of Mirkwood-water. Thus she passed through the Hall, and those elders were stirred in their hearts when they beheld her beauty. But she opened the door of the Women’s-Chamber, and stood on the threshold; and lo, there sat the carline amidst a ring of the Wolfing women, and she telling them tales of old time such as they had not yet heard; and her eyes were glittering, and the sweet words were flowing from her mouth; but she sat straight up like a young woman; and at whiles it seemed to those who hearkened, that she was no old and outworn woman, but fair and strong, and of much avail. But when she heard the Hall-Sun she turned and saw her on the threshold, and her speech fell suddenly, and all that might and briskness faded from her, and she fixed her eyes on the Hall-Sun and looked wistfully and anxiously on her.

Then spake the Hall-Sun standing in the doorway:

“Hear ye a matter, maidens, and ye Wolfing women all,

And thou alien guest of the Wolfings! But come ye up the hall,

That the ancient men may hearken: for methinks I have a word

Of the battle of the Kindreds, and the harvest of the sword.”

Then all arose up with great joy, for they knew that the tidings were good, when they looked on the face of the Hall-Sun and beheld the pride of her beauty unmarred by doubt or pain.

She led them forth to the dais, and there were the sick and the elders gathered and some ancient men of the thralls: so she stepped lightly up to her place, and stood under her namesake, the wondrous lamp of ancient days. And thus she spake:

“On my soul there lies no burden, and no tangle of the fight

In plain or dale or wild-wood enmeshes now my sight.

I see the Markmen’s wain-burg, and I see their warriors go

As men who wait for battle and the coming of the foe.

And they pass ’twixt the wood and the wain-burg within earshot of the horn,

But over the windy meadows no sound thereof is borne,

And all is well amongst them. To the burg I draw anigh

And I see all battle-banners in the breeze of morning fly,

But no Wolfings round their banner and no warrior of the Shield,

No Geiring and no Hrossing in the burg or on the field.”

She held her peace for a little while, and no one dared to speak; then she lifted up her head and spake:

“Now I go by the lip of the wild-wood and a sound withal I hear,

As of men in the paths of the thicket, and a many drawing anear.

Then, muffled yet by the tree-boles, I hear the Shielding song,

And warriors blithe and merry with the battle of the strong.

Give back a little, Markmen, make way for men to pass

To your ordered battle-dwelling o’er the trodden meadow-grass,

For alive with men is the wild-wood and shineth with the steel,

And hath a voice most merry to tell of the Kindreds’ weal,

’Twixt each tree a warrior standeth come back from the spear-strewn way,

And forth they come from the wild-wood and a little band are they.”

Then again was she silent; but her head sank not, as of one thinking, as before it did, but she looked straight forward with bright eyes and smiling, as she said:

“Lo, now the guests they are bringing that ye have not seen before;

Yet guests but ill-entreated; for they lack their shields of war,

No spear in the hand they carry and with no sax are girt.

Lo, these are the dreaded foemen, these once so strong to hurt;

The men that all folk fled from, the swift to drive the spoil,

The men that fashioned nothing but the trap to make men toil.

They drew the sword in the cities, they came and struck the stroke

And smote the shield of the Markmen, and point and edge they broke.

They drew the sword in the war-garth, they swore to bring aback

God’s gifts from the Markmen houses where the tables never lack.

O Markmen, take the God-gifts that came on their own feet

O’er the hills through the Mirkwood thicket the Stone of Tyr to meet!”

Again she stayed her song, which had been loud and joyous, and they who heard her knew that the Kindreds had gained the day, and whilst the Hall-Sun was silent they fell to talking of this fair day of battle and the taking of captives. But presently she spread out her hands again and they held their peace, and she said:

“I see, O Wolfing women, and many a thing I see,

But not all things, O elders, this eve shall ye learn of me,

For another mouth there cometh: the thicket I behold

And the Sons of Tyr amidst it, and I see the oak-trees old,

And the war-shout ringing round them; and I see the battle-lord

Unhelmed amidst of the mighty; and I see his leaping sword;

Strokes struck and warriors falling, and the streaks of spears I see,

But hereof shall the other tell you who speaketh after me.

For none other than the Shieldings from out the wood have come,

And they shift the turn with the Daylings to drive the folk-spear home,

And to follow with the Wolfings and thrust the war-beast forth.

And so good men deem the tidings that they bid them journey north

On the feet of a Shielding runner, that Gisli hath to name;

And west of the water he wendeth by the way that the Wolfings came;

Now for sleep he tarries never, and no meat is in his mouth

Till the first of the Houses hearkeneth the tidings of the south;

Lo, he speaks, and the mead-sea sippeth, and the bread by the way doth eat,

And over the Geiring threshold and outward pass his feet;

And he breasts the Burg of the Daylings and saith his happy word,

And stayeth to drink for a minute of the waves of Battleford.

Lone then by the stream he runneth, and wendeth the wild-wood road,

And dasheth through the hazels of the Oselings’ fair abode,

And the Elking women know it, and their hearts are glad once more,

And ye—yea, hearken, Wolfings, for his feet are at the door.”

CHAPTER XII—TIDINGS OF THE BATTLE IN MIRKWOOD

As the Hall-Sun made an end they heard in good sooth the feet of the runner on the hard ground without the hall, and presently the door opened and he came leaping over the threshold, and up to the table, and stood leaning on it with one hand, his breast heaving with his last swift run. Then he spake presently:

“I am Gisli of the Shieldings: Otter sendeth me to the Hall-Sun; but on the way I was to tell tidings to the Houses west of the Water: so have I done. Now is my journey ended; for Otter saith: ‘Let the Hall-Sun note the tidings and send word of them by four of the lightest limbed of the women, or by lads a-horseback, both west and east of the Water; let her send the word as it seemeth to her, whether she hath seen it or not. I will drink a short draught since my running is over.”

Then a damsel brought him a horn of mead and let it come into his hand, and he drank sighing with pleasure, while the damsel for pleasure of him and his tidings laid her hand on his shoulder. Then he set down the horn and spake:

“We, the Shieldings, with the Geirings, the Hrossings, and the Wolfings, three hundred warriors and more, were led into the Wood by Thiodolf the War-duke, beside whom went Fox, who hath seen the Romans. We were all afoot; for there is no wide way through the Wood, nor would we have it otherwise, lest the foe find the thicket easy. But many of us know the thicket and its ways; so we made not the easy hard. I was near the War-duke, for I know the thicket and am light-foot: I am a bowman. I saw Thiodolf that he was unhelmed and bore no shield, nor had he any coat of fence; nought but a deer-skin frock.”

As he said that word, the carline, who had drawn very near to him and was looking hard at his face, turned and looked on the Hall-Sun and stared at her till she reddened under those keen eyes: for in her heart began to gather some knowledge of the tale of her mother and what her will was.

But Gisli went on: “Yet by his side was his mighty sword, and we all knew it for Throng-plough, and were glad of it and of him and the unfenced breast of the dauntless. Six hours we went spreading wide through the thicket, not always seeing one another, but knowing one another to be nigh; those that knew the thicket best led, the others followed on. So we went till it was high noon on the plain and glimmering dusk in the thicket, and we saw nought, save here and there a roe, and here and there a sounder of swine, and coneys where it was opener, and the sun shone and the grass grew for a little space. So came we unto where the thicket ended suddenly, and there was a long glade of the wild-wood, all set about with great oak-trees and grass thereunder, which I knew well; and thereof the tale tells that it was a holy place of the folk who abided in these parts before the Sons of the Goths. Now will I drink.”

So he drank of the horn and said: “It seemeth that Fox had a deeming of the way the Romans should come; so now we abided in the thicket without that glade and lay quiet and hidden, spreading ourselves as much about that lawn of the oak-trees as we might, the while Fox and three others crept through the wood to espy what might be toward: not long had they been gone ere we heard a war-horn blow, and it was none of our horns: it was a long way off, but we looked to our weapons: for men are eager for the foe and the death that cometh, when they lie hidden in the thicket. A while passed, and again we heard the horn, and it was nigher and had a marvellous voice; then in a while was a little noise of men, not their voices, but footsteps going warily through the brake to the south, and twelve men came slowly and warily into that oak-lawn, and lo, one of them was Fox; but he was clad in the raiment of the dastard of the Goths whom he had slain. I tell you my heart beat, for I saw that the others were Roman men, and one of them seemed to be a man of authority, and he held Fox by the shoulder, and pointed to the thicket where we lay, and something he said to him, as we saw by his gesture and face, but his voice we heard not, for he spake soft.

“Then of those ten men of his he sent back two, and Fox going between them, as though he should be slain if he misled them; and he and the eight abided there wisely and warily, standing silently some six feet from each other, moving scarce at all, but looking like images fashioned of brown copper and iron; holding their casting-spears (which be marvellous heavy weapons) and girt with the sax.

“As they stood there, not out of earshot of a man speaking in his wonted voice, our War-duke made a sign to those about him, and we spread very quietly to the right hand and the left of him once more, and we drew as close as might be to the thicket’s edge, and those who had bows the nighest thereto. Thus then we abided a while again; and again came the horn’s voice; for belike they had no mind to come their ways covertly because of their pride.

“Soon therewithal comes Fox creeping back to us, and I saw him whisper into the ear of the War-duke, but heard not the word he said. I saw that he had hanging to him two Roman saxes, so I deemed he had slain those two, and so escaped the Romans. Maidens, it were well that ye gave me to drink again, for I am weary and my journey is done.”

So again they brought him the horn, and made much of him; and he drank, and then spake on.

“Now heard we the horn’s voice again quite close, and it was sharp and shrill, and nothing like to the roar of our battle-horns: still was the wood and no wind abroad, not even down the oak-lawn; and we heard now the tramp of many men as they thrashed through the small wood and bracken of the thicket-way; and those eight men and their leader came forward, moving like one, close up to the thicket where I lay, just where the path passed into the thicket beset by the Sons of the Goths: so near they were that I could see the dints upon their armour, and the strands of the wire on their sax-handles. Down then bowed the tall bracken on the further side of the wood-lawn, the thicket crashed before the march of men, and on they strode into the lawn, a goodly band, wary, alert, and silent of cries.

“But when they came into the lawn they spread out somewhat to their left hands, that is to say on the west side, for that way was the clear glade; but on the east the thicket came close up to them and edged them away. Therein lay the Goths.

“There they stayed awhile, and spread out but a little, as men marching, not as men fighting. A while we let them be; and we saw their captain, no big man, but dight with very fair armour and weapons; and there drew up to him certain Goths armed, the dastards of the folk, and another unarmed, an old man bound and bleeding. With these Goths had the captain some converse, and presently he cried out two or three words of Welsh in a loud voice, and the nine men who were ahead shifted them somewhat away from us to lead down the glade westward.

“The prey had come into the net, but they had turned their faces toward the mouth of it.

“Then turned Thiodolf swiftly to the man behind him who carried the war-horn, and every man handled his weapons: but that man understood, and set the little end to his mouth, and loud roared the horn of the Markmen, and neither friend nor foe misdoubted the tale thereof. Then leaped every man to his feet, all bow-strings twanged and the cast-spears flew; no man forebore to shout; each as he might leapt out of the thicket and fell on with sword and axe and spear, for it was from the bowmen but one shaft and no more.

“Then might you have seen Thiodolf as he bounded forward like the wild-cat on the hare, how he had no eyes for any save the Roman captain. Foemen enough he had round about him after the two first bounds from the thicket; for the Romans were doing their best to spread, that they might handle those heavy cast-spears, though they might scarce do it, just come out of the thicket as they were, and thrust together by that onslaught of the kindreds falling on from two sides and even somewhat from behind. To right and left flashed Throng-plough, while Thiodolf himself scarce seemed to guide it: men fell before him at once, and close at his heels poured the Wolfing kindred into the gap, and in a minute of time was he amidst of the throng and face to face with the gold-dight captain.

“What with the sweep of Throng-plough and the Wolfing onrush, there was space about him for a great stroke; he gave a side-long stroke to his right and hewed down a tall Burgundian, and then up sprang the white blade, but ere its edge fell he turned his wrist, and drove the point through that Captain’s throat just above the ending of his hauberk, so that he fell dead amidst of his folk.

“All the four kindreds were on them now, and amidst them, and needs must they give way: but stoutly they fought; for surely no other warriors might have withstood that onslaught of the Markmen for the twinkling of an eye: but had the Romans had but the space to have spread themselves out there, so as to handle their shot-weapons, many a woman’s son of us had fallen; for no man shielded himself in his eagerness, but let the swiftness of the Onset of point-and-edge shield him; which, sooth to say, is often a good shield, as here was found.

“So those that were unslain and unhurt fled west along the glade, but not as dastards, and had not Thiodolf followed hard in the chase according to his wont, they might even yet have made a fresh stand and spread from oak-tree to oak-tree across the glade: but as it befel, they might not get a fair offing so as to disentangle themselves and array themselves in good order side by side; and whereas the Markmen were fleet of foot, and in the woods they knew, there were a many aliens slain in the chase or taken alive unhurt or little hurt: but the rest fled this way and that way into the thicket, with whom were some of the Burgundians; so there they abide now as outcasts and men unholy, to be slain as wild-beasts one by one as we meet them.

“Such then was the battle in Mirkwood. Give me the mead-horn that I may drink to the living and the dead, and the memory of the dead, and the deeds of the living that are to be.”

So they brought him the horn, and he waved it over his head and drank again and spake:

“Sixty and three dead men of the Romans we counted there up and down that oak-glade; and we cast earth over them; and three dead dastards of the Goths, and we left them for the wolves to deal with. And twenty-five men of the Romans we took alive to be for hostages if need should be, and these did we Shielding men, who are not very many, bring aback to the wain-burg; and the Daylings, who are a great company, were appointed to enter the wood and be with Thiodolf; and me did Otter bid to bear the tidings, even as I have told you. And I have not loitered by the way.”

Great then was the joy in the Hall; and they took Gisli, and made much of him, and led him to the bath, and clad him in fine raiment taken from the coffer which was but seldom opened, because the cloths it held were precious; and they set a garland of green wheat-ears on his head. Then they fell to and spread the feast in the hall; and they ate and drank and were merry.

But as for speeding the tidings, the Hall-Sun sent two women and two lads, all a-horseback, to bear the words: the women to remember the words which she taught them carefully, the lads to be handy with the horses, or in the ford, or the swimming of the deeps, or in the thicket. So they went their ways, down the water: one pair went on the western side, and the other crossed Mirkwood-water at the shallows (for being Midsummer the water was but small), and went along the east side, so that all the kindred might know of the tidings and rejoice.

Great was the glee in the Hall, though the warriors of the House were away, and many a song and lay they sang: but amidst the first of the singing they bethought them of the old woman, and would have bidden her tell them some tale of times past, since she was so wise in the ancient lore. But when they sought for her on all sides she was not to be found, nor could anyone remember seeing her depart from the Hall. But this had they no call to heed, and the feast ended, as it began, in great glee.

Albeit the Hall-Sun was troubled about the carline, both that she had come, and that she had gone: and she determined that the next time she met her she would strive to have of her a true tale of what she was, and of all that was toward.

CHAPTER XIII—THE HALL-SUN SAITH ANOTHER WORD

It was no later than the next night, and a many of what thralls were not with the host were about in the feast-hall with the elders and lads and weaklings of the House; for last night’s tidings had drawn them thither. Gisli had gone back to his kindred and the wain-burg in the Upper-mark, and the women were sitting, most of them, in the Women’s-Chamber, some of them doing what little summer work needed doing about the looms, but more resting from their work in field and acre.

Then came the Hall-Sun forth from her room clad in glittering raiment, and summoned no one, but went straight to her place on the dais under her namesake the Lamp, and stood there a little without speaking. Her face was pale now, her lips a little open, her eyes set and staring as if they saw nothing of all that was round about her.