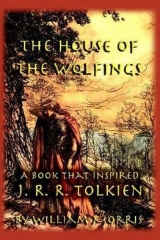

Текст книги "The House of the Wolfings"

Автор книги: William Morris

Жанры:

Историческое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

“But they told us that they were a house of the folk of the herdsmen, and that there was war in the land, and that the people thereof were fleeing before the cruelty of a host of warriors, men of a mighty folk, such as the earth hath not heard of, who dwell in great cities far to the south; and how that this host had crossed the mountains, and the Great Water that runneth from them, and had fallen upon their kindred, and overcome their fighting-men, and burned their dwellings, slain their elders, and driven their neat and their sheep, yea, and their women and children in no better wise than their neat and sheep.

“And they said that they had fled away thus far from their old habitations, which were a long way to the south, and were now at point to build them dwellings there in that Dale of the Hazels, and to trust to it that these Welshmen, whom they called Romans, would not follow so far, and that if they did, they might betake them to the wild-wood, and let the thicket cover them, they being so nigh to it.

“Thus they told us; wherefore we sent back one of our fellowship, Birsti of the Geirings, to tell the tale; and one of the herdsmen folk went with him, but we ourselves went onward to hear more of these Romans; for the folk when we asked them, said that they had been in battle against them, but had fled away for fear of their rumour only. Therefore we went on, and a young man of this kindred, who named themselves the Hrutings of the Fell-folk, went along with us. But the others were sore afeard, for all they had weapons.

“So as we went up the land we found they had told us the very sooth, and we met divers Houses, and bands, and broken men, who were fleeing from this trouble, and many of them poor and in misery, having lost their flocks and herds as well as their roofs; and this last be but little loss to them, as their dwellings are but poor, and for the most part they have no tillage. Now of these men, we met not a few who had been in battle with the Roman host, and much they told us of their might not to be dealt with, and their mishandling of those whom they took, both men and women; and at the last we heard true tidings how they had raised them a garth, and made a stronghold in the midst of the land, as men who meant abiding there, so that neither might the winter drive them aback, and that they might be succoured by their people on the other side of the Great River; to which end they have made other garths, though not so great, on the road to that water, and all these well and wisely warded by tried men. For as to the Folks on the other side of the Water, all these lie under their hand already, what by fraud what by force, and their warriors go with them to the battle and help them; of whom we met bands now and again, and fought with them, and took men of them, who told us all this and much more, over long to tell of here.”

He paused and turned about to look on the mighty assembly, and his ears drank in the long murmur that followed his speaking, and when it had died out he spake again, but in rhyme:

“Lo thus much of my tidings! But this too it behoveth to tell,

That these masterful men of the cities of the Markmen know full well:

And they wot of the well-grassed meadows, and the acres of the Mark,

And our life amidst of the wild-wood like a candle in the dark;

And they know of our young men’s valour and our women’s loveliness,

And our tree would they spoil with destruction if its fruit they may never possess.

For their lust is without a limit, and nought may satiate

Their ravening maw; and their hunger if ye check it turneth to hate,

And the blood-fever burns in their bosoms, and torment and anguish and woe

O’er the wide field ploughed by the sword-blade for the coming years they sow;

And ruth is a thing forgotten and all hopes they trample down;

And whatso thing is steadfast, whatso of good renown,

Whatso is fair and lovely, whatso is ancient sooth

In the bloody marl shall they mingle as they laugh for lack of ruth.

Lo the curse of the world cometh hither; for the men that we took in the land

Said thus, that their host is gathering with many an ordered band

To fall on the wild-wood passes and flood the lovely Mark,

As the river over the meadows upriseth in the dark.

Look to it, O ye kindred! availeth now no word

But the voice of the clashing of iron, and the sword-blade on the sword.”

Therewith he made an end, and deeper and longer was the murmur of the host of freemen, amidst which Bork gat him down from the Speech-Hill, his weapons clattering about him, and mingled with the men of his kindred.

Then came forth a man of the kin of the Shieldings of the Upper-mark, and clomb the mound; and he spake in rhyme from beginning to end; for he was a minstrel of renown:

“Lo I am a man of the Shieldings and Geirmund is my name;

A half-moon back from the wild-wood out into the hills I came,

And I went alone in my war-gear; for we have affinity

With the Hundings of the Fell-folk, and with them I fain would be;

For I loved a maid of their kindred. Now their dwelling was not far

From the outermost bounds of the Fell-folk, and bold in the battle they are,

And have met a many people, and held their own abode.

Gay then was the heart within me, as over the hills I rode

And thought of the mirth of to-morrow and the sweet-mouthed Hunding maid

And their old men wise and merry and their young men unafraid,

And the hall-glee of the Hundings and the healths o’er the guesting cup.

But as I rode the valley, I saw a smoke go up

O’er the crest of the last of the grass-hills ’twixt me and the Hunding roof,

And that smoke was black and heavy: so a while I bided aloof,

And drew my girths the tighter, and looked to the arms I bore

And handled my spear for the casting; for my heart misgave me sore,

For nought was that pillar of smoke like the guest-fain cooking-fire.

I lingered in thought for a minute, then turned me to ride up higher,

And as a man most wary up over the bent I rode,

And nigh hid peered o’er the hill-crest adown on the Hunding abode;

And forsooth ’twas the fire wavering all o’er the roof of old,

And all in the garth and about it lay the bodies of the bold;

And bound to a rope amidmost were the women fair and young,

And youths and little children, like the fish on a withy strung

As they lie on the grass for the angler before the beginning of night.

Then the rush of the wrath within me for a while nigh blinded my sight;

Yet about the cowering war-thralls, short dark-faced men I saw,

Men clad in iron armour, this way and that way draw,

As warriors after the battle are ever wont to do.

Then I knew them for the foemen and their deeds to be I knew,

And I gathered the reins together to ride down the hill amain,

To die with a good stroke stricken and slay ere I was slain.

When lo, on the bent before me rose the head of a brown-faced man,

Well helmed and iron-shielded, who some Welsh speech began

And a short sword brandished against me; then my sight cleared and I saw

Five others armed in likewise up hill and toward me draw,

And I shook the spear and sped it and clattering on his shield

He fell and rolled o’er smitten toward the garth and the Fell-folk’s field.

“But my heart changed with his falling and the speeding of my stroke,

And I turned my horse; for within me the love of life awoke,

And I spurred, nor heeded the hill-side, but o’er rough and smooth I rode

Till I heard no chase behind me; then I drew rein and abode.

And down in a dell was I gotten with a thorn-brake in its throat,

And heard but the plover’s whistle and the blackbird’s broken note

’Mid the thorns; when lo! from a thorn-twig away the blackbird swept,

And out from the brake and towards me a naked man there crept,

And straight I rode up towards him, and knew his face for one

I had seen in the hall of the Hundings ere its happy days were done.

I asked him his tale, but he bade me forthright to bear him away;

So I took him up behind me, and we rode till late in the day,

Toward the cover of the wild-wood, and as swiftly as we might.

But when yet aloof was the thicket and it now was moonless night,

We stayed perforce for a little, and he told me all the tale:

How the aliens came against them, and they fought without avail

Till the Roof o’er their heads was burning and they burst forth on the foe,

And were hewn down there together; nor yet was the slaughter slow.

But some they saved for thralldom, yea, e’en of the fighting men,

Or to quell them with pains; so they stripped them; and this man espying just then

Some chance, I mind not whatwise, from the garth fled out and away.

“Now many a thing noteworthy of these aliens did he say,

But this I bid you hearken, lest I wear the time for nought,

That still upon the Markmen and the Mark they set their thought;

For they questioned this man and others through a go-between in words

Of us, and our lands and our chattels, and the number of our swords;

Of the way and the wild-wood passes and the winter and his ways.

Now look to see them shortly; for worn are fifteen days

Since in the garth of the Hundings I saw them dight for war,

And a hardy folk and ready and a swift-foot host they are.”

Therewith Geirmund went down clattering from the Hill and stood with his company. But a man came forth from the other side of the ring, and clomb the Hill: he was a red-haired man, rather big, clad in a skin coat, and bearing a bow in his hand and a quiver of arrows at his back, and a little axe hung by his side. He said:

“I dwell in the House of the Hrossings of the Mid-mark, and I am now made a man of the kindred: howbeit I was not born into it; for I am the son of a fair and mighty woman of a folk of the Kymry, who was taken in war while she went big with me; I am called Fox the Red.

“These Romans have I seen, and have not died: so hearken! for my tale shall be short for what there is in it.

“I am, as many know, a hunter of Mirkwood, and I know all its ways and the passes through the thicket somewhat better than most.

“A moon ago I fared afoot from Mid-mark through Upper-mark into the thicket of the south, and through it into the heath country; and I went over a neck and came in the early dawn into a little dale when somewhat of mist still hung over it. At the dale’s end I saw a man lying asleep on the grass under a quicken tree, and his shield and sword hanging over his head to a bough thereof, and his horse feeding hoppled higher up the dale.

“I crept up softly to him with a shaft nocked on the string, but when I drew near I saw him to be of the sons of the Goths. So I doubted nothing, but laid down my bow, and stood upright, and went to him and roused him, and he leapt up, and was wroth.

“I said to him, ‘Wilt thou be wroth with a brother of the kindred meeting him in unpeopled parts?’

“But he reached out for his weapons; but ere he could handle them I ran in on him so that he gat not his sword, and had scant time to smite at me with a knife which he drew from his waist.

“I gave way before him for he was a very big man, and he rushed past me, and I dealt him a blow on the side of the head with my little axe which is called the War-babe, and gave him a great wound: and he fell on the grass, and as it happened that was his bane.

“I was sorry that I had slain him, since he was a man of the Goths: albeit otherwise he had slain me, for he was very wroth and dazed with slumber.

“He died not for a while; and he bade me fetch him water; and there was a well hard by on the other side of the tree; so I fetched it him in a great shell that I carry, and he drank. I would have sung the blood-staunching song over him, for I know it well. But he said, ‘It availeth nought: I have enough: what man art thou?’

“I said, ‘I am a fosterling of the Hrossings, and my mother was taken in war: my name is Fox.’

“Said he; ‘O Fox, I have my due at thy hands, for I am a Markman of the Elkings, but a guest of the Burgundians beyond the Great River; and the Romans are their masters and they do their bidding: even so did I who was but their guest: and I a Markman to fight against the Markmen, and all for fear and for gold! And thou an alien-born hast slain their traitor and their dastard! This is my due. Give me to drink again.’

“So did I; and he said; ‘Wilt thou do an errand for me to thine own house?’ ‘Yea,’ said I.

“Said he, ‘I am a messenger to the garth of the Romans, that I may tell the road to the Mark, and lead them through the thicket; and other guides are coming after me: but not yet for three days or four. So till they come there will be no man in the Roman garth to know thee that thou art not even I myself. If thou art doughty, strip me when I am dead and do my raiment on thee, and take this ring from my neck, for that is my token, and when they ask thee for a word say, “No limit”; for that is the token-word. Go south-east over the dales keeping Broadshield-fell square with thy right hand, and let thy wisdom, O Fox, lead thee to the Garth of the Romans, and so back to thy kindred with all tidings thou hast gathered—for indeed they come—a many of them. Give me to drink.’

“So he drank again, and said, ‘The bearer of this token is called Hrosstyr of the River Goths. He hath that name among dastards. Thou shalt lay a turf upon my head. Let my death pay for my life.’

“Therewith he fell back and died. So I did as he bade me and took his gear, worth six kine, and did it on me; I laid turf upon him in that dale, and hid my bow and my gear in a blackthorn brake hard by, and then took his horse and rode away.

“Day and night I rode till I came to the garth of the Romans; there I gave myself up to their watchers, and they brought me to their Duke, a grim man and hard. He said in a terrible voice, ‘Thy name?’ I said, ‘Hrosstyr of the River Goths.’ He said, ‘What limit?’ I answered, ‘No limit.’ ‘The token!’ said he, and held out his hand. I gave him the ring. ‘Thou art the man,’ said he.

“I thought in my heart, ‘thou liest, lord,’ and my heart danced for joy.

“Then he fell to asking me questions a many, and I answered every one glibly enough, and told him what I would, but no word of truth save for his hurt, and my soul laughed within me at my lies; thought I, the others, the traitors, shall come, and they shall tell him the truth, and he will not trow it, or at the worst he will doubt them. But me he doubted nothing, else had he called in the tormentors to have the truth of me by pains; as I well saw afterwards, when they questioned with torments a man and a woman of the hill-folk whom they had brought in captive.

“I went from him and went all about that garth espying everything, fearing nothing; albeit there were divers woful captives of the Goths, who cursed me for a dastard, when they saw by my attire that I was of their blood.

“I abode there three days, and learned all that I might of the garth and the host of them, and the fourth day in the morning I went out as if to hunt, and none hindered me, for they doubted me not.

“So I came my ways home to the Upper-mark, and was guested with the Geirings. Will ye that I tell you somewhat of the ways of these Romans of the garth? The time presses, and my tale runneth longer than I would. What will ye?”

Then there arose a murmur, “Tell all, tell all.” “Nay,” said the Fox, “All I may not tell; so much did I behold there during the three days’ stay; but this much it behoveth you to know: that these men have no other thought save to win the Mark and waste it, and slay the fighting men and the old carles, and enthrall such as they will, that is, all that be fair and young, and they long sorely for our women either to have or to sell.

“As for their garth, it is strongly walled about with a dyke newly dug; on the top thereof are they building a wall made of clay, and burned like pots into ashlar stones hard and red, and these are laid in lime.

“It is now the toil of the thralls of our blood whom they have taken, both men and women, to dig that clay and to work it, and bear it to kilns, and to have for reward scant meat and many stripes. For it is a grim folk, that laugheth to see others weep.

“Their men-at-arms are well dight and for the most part in one way: they are helmed with iron, and have iron on their breasts and reins, and bear long shields that cover them to the knees. They are girt with a sax and have a heavy casting-spear. They are dark-skinned and ugly of aspect, surly and of few words: they drink little, and eat not much.

“They have captains of tens and of hundreds over them, and that war-duke over all; he goeth to and fro with gold on his head and his breast, and commonly hath a cloak cast over him of the colour of the crane’s-bill blossom.

“They have an altar in the midst of their burg, and thereon they sacrifice to their God, who is none other than their banner of war, which is an image of the ravening eagle with outspread wings; but yet another God they have, and look you! it is a wolf, as if they were of the kin of our brethren; a she-wolf and two man-children at her dugs; wonderful is this.

“I tell you that they are grim; and know it by this token: those captains of tens, and of hundreds, spare not to smite the warriors with staves even before all men, when all goeth not as they would; and yet, though they be free men, and mighty warriors, they endure it and smite not in turn. They are a most evil folk.

“As to their numbers, they of the burg are hard on three thousand footmen of the best; and of horsemen five hundred, nowise good; and of bowmen and slingers six hundred or more: their bows weak; their slingers cunning beyond measure. And the talk is that when they come upon us they shall have with them some five hundred warriors of the Over River Goths, and others of their own folk.”

Then he said:

“O men of the Mark, will ye meet them in the meadows and the field,

Or will ye flee before them and have the wood for a shield?

Or will ye wend to their war-burg with weapons cast away,

With your women and your children, a peace of them to pray?

So doing, not all shall perish; but most shall long to die

Ere in the garths of the Southland two moons have loitered by.”

Then rose the rumour loud and angry mingled with the rattle of swords and the clash of spears on shields; but Fox said:

“Needs must ye follow one of these three ways. Nay, what say I? there are but two ways and not three; for if ye flee they shall follow you to the confines of the earth. Either these Welsh shall take all, and our lives to boot, or we shall hold to all that is ours, and live merrily. The sword doometh; and in three days it may be the courts shall be hallowed: small is the space between us.”

Therewith he also got him down from the Hill, and joined his own house: and men said that he had spoken well and wisely. But there arose a noise of men talking together on these tidings; and amidst it an old warrior of the Nether-mark strode forth and up to the Hill-top. Gaunt and stark he was to look on; and all men knew him and he was well-beloved, so all held their peace as he said:

“I am Otter of the Laxings: now needeth but few words till the War-duke is chosen, and we get ready to wend our ways in arms. Here have ye heard three good men and true tell of our foes, and this last, Fox the Red, hath seen them and hath more to tell when we are on the way; nor is the way hard to find. It were scarce well to fall upon these men in their garth and war-burg; for hard is a wall to slay. Better it were to meet them in the Wild-wood, which may well be a friend to us and a wall, but to them a net. O Agni of the Daylings, thou warder of the Thing-stead, bid men choose a War-duke if none gainsay it.”

And without more words he clattered down the Hill, and went and stood with the Laxing band. But the old Dayling arose and blew the horn, and there was at once a great silence, amidst which he said:

“Children of Slains-father, doth the Folk go to the war?”

There was no voice but shouted “yea,” and the white swords sprang aloft, and the westering sun swept along a half of them as they tossed to and fro, and the others showed dead-white and fireless against the dark wood.

Then again spake Agni:

“Will ye choose the War-duke now and once, or shall it be in a while, after others have spoken?”

And the voice of the Folk went up, “Choose! Choose!”

Said Agni: “Sayeth any aught against it?” But no voice of a gainsayer was heard, and Agni said:

“Children of Tyr, what man will ye have for a leader and a duke of war?”

Then a great shout sprang up from amidst the swords: “We will have Thiodolf; Thiodolf the Wolfing!”

Said Agni: “I hear no other name; are ye of one mind? hath any aught to say against it? If that be so, let him speak now, and not forbear to follow in the wheatfield of the spears. Speak, ye that will not follow Thiodolf!”

No voice gainsaid him: then said the Dayling: “Come forth thou War-duke of the Markmen! take up the gold ring from the horns of the altar, set it on thine arm and come up hither!”

Then came forth Thiodolf into the sun, and took up the gold ring from where it lay, and did it on his arm. And this was the ring of the leader of the folk whenso one should be chosen: it was ancient and daintily wrought, but not very heavy: so ancient it was that men said it had been wrought by the dwarfs.

So Thiodolf went up on to the hill, and all men cried out on him for joy, for they knew his wisdom in war. Many wondered to see him unhelmed, but they had a deeming that he must have made oath to the Gods thereof and their hearts were glad of it. They took note of the dwarf-wrought hauberk, and even from a good way off they could see what a treasure of smith’s work it was, and they deemed it like enough that spells had been sung over it to make it sure against point and edge: for they knew that Thiodolf was well beloved of the Gods.

But when Thiodolf was on the Hill of Speech, he said:

“Men of the kindreds, I am your War-duke to-day; but it is oftenest the custom when ye go to war to choose you two dukes, and I would it were so now. No child’s play is the work that lies before us; and if one leader chance to fall let there be another to take his place without stop or stay. Thou Agni of the Daylings, bid the Folk choose them another duke if so they will.”

Said Agni: “Good is this which our War-duke hath spoken; say then, men of the Mark, who shall stand with Thiodolf to lead you against the aliens?”

Then was there a noise and a crying of names, and more than two names seemed to be cried out; but by far the greater part named either Otter of the Laxings, or Heriulf of the Wolfings. True it is that Otter was a very wise warrior, and well known to all the men of the Mark; yet so dear was Heriulf to them, that none would have named Otter had it not been mostly their custom not to choose both War-dukes from one House.

Now spake Agni: “Children of Tyr, I hear you name more than one name: now let each man cry out clearly the name he nameth.”

So the Folk cried the names once more, but this time it was clear that none was named save Otter and Heriulf; so the Dayling was at point to speak again, but or ever a word left his lips, Heriulf the mighty, the ancient of days, stood forth: and when men saw that he would take up the word there was a great silence. So he spake:

“Hearken, children! I am old and war-wise; but my wisdom is the wisdom of the sword of the mighty warrior, that knoweth which way it should wend, and hath no thought of turning back till it lieth broken in the field. Such wisdom is good against Folks that we have met heretofore; as when we have fought with the Huns, who would sweep us away from the face of the earth, or with the Franks or the Burgundians, who would quell us into being something worser than they be. But here is a new foe, and new wisdom, and that right shifty, do we need to meet them. One wise duke have ye gotten, Thiodolf to wit; and he is young beside me and beside Otter of the Laxings. And now if ye must needs have an older man to stand beside him, (and that is not ill) take ye Otter; for old though his body be, the thought within him is keen and supple like the best of Welsh-wrought blades, and it liveth in the days that now are: whereas for me, meseemeth, my thoughts are in the days bygone. Yet look to it, that I shall not fail to lead as the sword of the valiant leadeth, or the shaft shot by the cunning archer. Choose ye Otter; I have spoken over long.”

Then spoke Agni the Dayling, and laughed withal: “One man of the Folk hath spoken for Otter and against Heriulf—now let others speak if they will!”

So the cry came forth, “Otter let it be, we will have Otter!”

“Speaketh any against Otter?” said Agni. But there was no voice raised against him.

Then Agni said: “Come forth, Otter of the Laxings, and hold the ring with Thiodolf.”

Then Otter went up on to the hill and stood by Thiodolf, and they held the ring together; and then each thrust his hand and arm through the ring and clasped hands together, and stood thus awhile, and all the Folk shouted together.

Then spake Agni: “Now shall we hew the horses and give the gifts to the Gods.”

Therewith he and the two War-dukes came down from the hill; and stood before the altar; and the nine warriors of the Daylings stood forth with axes to hew the horses and with copper bowls wherein to catch the blood of them, and each hewed down his horse to the Gods, but the two War-dukes slew the tenth and fairest: and the blood was caught in the bowls, and Agni took a sprinkler and went round about the ring of men, and cast the blood of the Gods’-gifts over the Folk, as was the custom of those days.

Then they cut up the carcases and burned on the altar the share of the Gods, and Agni and the War-dukes tasted thereof, and the rest they bore off to the Daylings’ abode for the feast to be holden that night.

Then Otter and Thiodolf spake apart together for awhile, and presently went up again on to the Speech-Hill, and Thiodolf said:

“O kindreds of the Markmen; to-morrow with the day

We shall wend up Mirkwood-water to bar our foes the way;

And there shall we make our wain-burg on the edges of the wood,

Where in the days past over at last the aliens stood,

The Slaughter Tofts ye call it. There tidings shall we get

If the curse of the world is awakened, and the serpent crawleth yet

Amidst the Mirkwood thicket; and when the sooth we know,

Then bearing battle with us through the thicket shall we go,

The ancient Wood-wolf’s children, and the People of the Shield,

And the Spear-kin and the Horse-kin, while the others keep the field

About the warded wain-burg; for not many need we there

Where amidst of the thickets’ tangle and the woodland net they fare,

And the hearts of the aliens falter and they curse the fight ne’er done,

And wonder who is fighting and which way is the sun.”

Thus he spoke; then Agni took up the war-horn again, and blew a blast, and then he cried out:

“Now sunder we the Folk-mote! and the feast is for to-night,

And to-morrow the Wayfaring; But unnamed is the day of the fight;

O warriors, look ye to it that not long we need abide

’Twixt the hour of the word we have spoken, and our fair-fame’s blooming tide!

For then ’midst the toil and the turmoil shall we sow the seeds of peace,

And the Kindreds’ long endurance, and the Goth-folk’s great increase.”

Then arose the last great shout, and soberly and in due order, kindred by kindred, they turned and departed from the Thing-stead and went their way through the wood to the abode of the Daylings.

CHAPTER IX—THE ANCIENT MAN OF THE DAYLINGS

There still hung the more part of the stay-at-homes round about the Roof. But on the plain beneath the tofts were all the wains of the host drawn up round about a square like the streets about a market-place; all these now had their tilts rigged over them, some white, some black, some red, some tawny of hue; and some, which were of the Beamings, green like the leafy tree.

The warriors of the host went down into this wain-town, which they had not fenced in any way, since they in no wise looked for any onset there; and there were their thralls dighting the feast for them, and a many of the Dayling kindred, both men and women, went with them; but some men did the Daylings bring into their Roof, for there was room for a good many besides their own folk. So they went over the Bridge of turf into the garth and into the Great Roof of the Daylings; and amongst these were the two War-dukes.

So when they came to the dais it was as fair all round about there as might well be; and there sat elders and ancient warriors to welcome the guests; and among them was the old carle who had sat on the edge of the burg to watch the faring of the host, and had shuddered back at the sight of the Wolfing Banner.

And when the old carle saw the guests, he fixed his eyes on Thiodolf, and presently came up and stood before him; and Thiodolf looked on the old man, and greeted him kindly and smiled on him; but the carle spake not till he had looked on him a while; and at last he fell a-trembling, and reached his hands out to Thiodolf’s bare head, and handled his curls and caressed them, as a mother does with her son, even if he be a grizzled-haired man, when there is none by: and at last he said:

“How dear is the head of the mighty, and the apple of the tree

That blooms with the life of the people which is and yet shall be!

It is helmed with ancient wisdom, and the long remembered thought,

That liveth when dead is the iron, and its very rust but nought.

Ah! were I but young as aforetime, I would fare to the battle-stead

And stand amidst of the spear-hail for the praise of the hand and the head!”

Then his hands left Thiodolf’s head, and strayed down to his shoulders and his breast, and he felt the cold rings of the hauberk, and let his hands fall down to his side again; and the tears gushed out of his old eyes and again he spake: