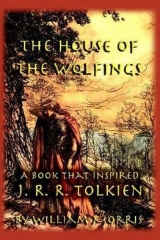

Текст книги "The House of the Wolfings"

Автор книги: William Morris

Жанры:

Историческое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

For the Goth-folk to cherish with gold gaining hand.’

“See ye how the Lay tells that the hall was bolder than the men, who fled from it, and left all for our fellowship to deal with in the days gone by?”

Said the Wolfing man:

“And as it was once, so shall it be again. Maybe we shall go far on this journey, and see at least one of the garths of the Southlands, even those which they call cities. For I have heard it said that they have more cities than one only, and that so great are their kindreds, that each liveth in a garth full of mighty houses, with a wall of stone and lime around it; and that in every one of these garths lieth wealth untold heaped up. And wherefore should not all this fall to the Markmen and their valiancy?”

Said the Elking:

“As to their many cities and the wealth of them, that is sooth; but as to each city being the habitation of each kindred, it is otherwise: for rather it may be said of them that they have forgotten kindred, and have none, nor do they heed whom they wed, and great is the confusion amongst them. And mighty men among them ordain where they shall dwell, and what shall be their meat, and how long they shall labour after they are weary, and in all wise what manner of life shall be amongst them; and though they be called free men who suffer this, yet may no house or kindred gainsay this rule and order. In sooth they are a people mighty, but unhappy.”

Said Wolfkettle:

“And hast thou learned all this from the ancient story lays, O Hiarandi? For some of them I know, though not all, and therein have I noted nothing of all this. Is there some new minstrel arisen in thine House of a memory excelling all those that have gone before? If that be so, I bid him to the Roof of the Wolfings as soon as may be; for we lack new tales.”

“Nay,” said Hiarandi, “This that I tell thee is not a tale of past days, but a tale of to-day. For there came to us a man from out of the wild-wood, and prayed us peace, and we gave it him; and he told us that he was of a House of the Gael, and that his House had been in a great battle against these Welshmen, whom he calleth the Romans; and that he was taken in the battle, and sold as a thrall in one of their garths; and howbeit, it was not their master-garth, yet there he learned of their customs: and sore was the lesson! Hard was his life amongst them, for their thralls be not so well entreated as their draught-beasts, so many do they take in battle; for they are a mighty folk; and these thralls and those aforesaid unhappy freemen do all tilling and herding and all deeds of craftsmanship: and above these are men whom they call masters and lords who do nought, nay not so much as smithy their own edge-weapons, but linger out their days in their dwellings and out of their dwellings, lying about in the sun or the hall-cinders, like cur-dogs who have fallen away from kind.

“So this man made a shift to flee away from out of that garth, since it was not far from the great river; and being a valiant man, and young and mighty of body, he escaped all perils and came to us through the Mirkwood. But we saw that he was no liar, and had been very evilly handled, for upon his body was the mark of many a stripe, and of the shackles that had been soldered on to his limbs; also it was more than one of these accursed people whom he had slain when he fled. So he became our guest and we loved him, and he dwelt among us and yet dwelleth, for we have taken him into our House. But yesterday he was sick and might not ride with us; but may be he will follow on and catch up with us in a day or two. And if he come not, then will I bring him over to the Wolfings when the battle is done.”

Then laughed the Beaming man, and spake:

“How then if ye come not back, nor Wolfkettle, nor the Welsh Guest, nor I myself? Meseemeth no one of these Southland Cities shall we behold, and no more of the Southlanders than their war-array.”

“These are evil words,” said Wolfkettle, “though such an outcome must be thought on. But why deemest thou this?”

Said the Beaming: “There is no Hall-Sun sitting under our Roof at home to tell true tales concerning the Kindred every day. Yet forsooth from time to time is a word said in our Folk-hall for good or for evil; and who can choose but hearken thereto? And yestereve was a woeful word spoken, and that by a man-child of ten winters.”

Said the Elking: “Now that thou hast told us thus much, thou must tell us more, yea, all the word which was spoken; else belike we shall deem of it as worse than it was.”

Said the Beaming: “Thus it was; this little lad brake out weeping yestereve, when the Hall was full and feasting; and he wailed, and roared out, as children do, and would not be pacified, and when he was asked why he made that to do, he said: ‘Well away! Raven hath promised to make me a clay horse and to bake it in the kiln with the pots next week; and now he goeth to the war, and he shall never come back, and never shall my horse be made.’ Thereat we all laughed as ye may well deem. But the lad made a sour countenance on us and said, ‘why do ye laugh? look yonder, what see ye?’ ‘Nay,’ said one, ‘nought but the Feast-hall wall and the hangings of the High-tide thereon.’ Then said the lad sobbing: ‘Ye see ill: further afield see I: I see a little plain, on a hill top, and fells beyond it far bigger than our speech-hill: and there on the plain lieth Raven as white as parchment; and none hath such hue save the dead.’ Then said Raven, (and he was a young man, and was standing thereby). ‘And well is that, swain, to die in harness! Yet hold up thine heart; here is Gunbert who shall come back and bake thine horse for thee.’ ‘Nay never more,’ quoth the child, ‘For I see his pale head lying at Raven’s feet; but his body with the green gold-broidered kirtle I see not.’ Then was the laughter stilled, and man after man drew near to the child, and questioned him, and asked, ‘dost thou see me?’ ‘dost thou see me?’ And he failed to see but few of those that asked him. Therefore now meseemeth that not many of us shall see the cities of the South, and those few belike shall look on their own shackles therewithal.”

“Nay,” said Hiarandi, “What is all this? heard ye ever of a company of fighting men that fared afield, and found the foe, and came back home leaving none behind them?”

Said the Beaming: “Yet seldom have I heard a child foretell the death of warriors. I tell thee that hadst thou been there, thou wouldst have thought of it as if the world were coming to an end.”

“Well,” said Wolfkettle, “let it be as it may! Yet at least I will not be led away from the field by the foemen. Oft may a man be hindered of victory, but never of death if he willeth it.”

Therewith he handled a knife that hung about his neck, and went on to say: “But indeed, I do much marvel that no word came into the mouth of the Hall-Sun yestereven or this morning, but such as any woman of the kindred might say.”

Therewith fell their talk awhile, and as they rode they came to where the wood drew nigher to the river, and thus the Mid-mark had an end; for there was no House had a dwelling in the Mid-mark higher up the water than the Elkings, save one only, not right great, who mostly fared to war along with the Elkings: and this was the Oselings, whose banner bore the image of the Wood-ousel, the black bird with the yellow neb; and they had just fallen into the company of the greater House.

So now Mid-mark was over and past, and the serried trees of the wood came down like a wall but a little way from the lip of the water; and scattered trees, mostly quicken-trees grew here and there on the very water side. But Mirkwood-water ran deep swift and narrow between high clean-cloven banks, so that none could dream of fording, and not so many of swimming its dark green dangerous waters. And the day wore on towards evening and the glory of the western sky was unseen because of the wall of high trees. And still the host made on, and because of the narrowness of the space between river and wood it was strung out longer and looked a very great company of men. And moreover the men of the eastern-lying part of Mid-mark, were now marching thick and close on the other side of the river but a little way from the Wolfings and their fellows; for nothing but the narrow river sundered them.

So night fell, and the stars shone, and the moon rose, and yet the Wolfings and their fellows stayed not, since they wotted that behind them followed a many of the men of the Mark, both the Mid and the Nether, and they would by no means hinder their march.

So wended the Markmen between wood and stream on either side of Mirkwood-water, till now at last the night grew deep and the moon set, and it was hard on midnight, and they had kindled many torches to light them on either side of the water. So whereas they had come to a place where the trees gave back somewhat from the river, which was well-grassed for their horses and neat, and was called Baitmead, the companies on the western side made stay there till morning. And they drew the wains right up to the thick of the wood, and all men turned aside into the mead from the beaten road, so that those who were following after might hold on their way if so they would. There then they appointed watchers of the night, while the rest of them lay upon the sward by the side of the trees, and slept through the short summer night.

The tale tells not that any man dreamed of the fight to come in such wise that there was much to tell of his dream on the morrow; many dreamed of no fight or faring to war, but of matters little, and often laughable, mere mingled memories of bygone time that had no waking wits to marshal them.

But that man of the Beamings dreamed that he was at home watching a potter, a man of the thralls of the House working at his wheel, and fashioning bowls and ewers: and he had a mind to take of his clay and fashion a horse for the lad that had bemoaned the promise of his toy. And he tried long and failed to fashion anything; for the clay fell to pieces in his hands; till at last it held together and grew suddenly, not into an image of a horse, but of the Great Yule Boar, the similitude of the Holy Beast of Frey. So he laughed in his sleep and was glad, and leaped up and drew his sword with his clay-stained hands that he might wave it over the Earth Boar, and swear a great oath of a doughty deed. And therewith he found himself standing on his feet indeed, just awakened in the cold dawn, and holding by his right hand to an ash-sapling that grew beside him. So he laughed again, and laid him down, and leaned back and slept his sleep out till the sun and the voices of his fellows stirring awakened him.

CHAPTER VII—THEY GATHER TO THE FOLK-MOTE

When it was the morning, all the host of the Markmen was astir on either side of the water, and when they had broken their fast, they got speedily into array, and were presently on the road again; and the host was now strung out longer yet, for the space between water and wood once more diminished till at last it was no wider than ten men might go abreast, and looking ahead it was as if the wild-wood swallowed up both river and road.

But the fighting-men hastened on merrily with their hearts raised high, since they knew that they would soon be falling in with more of their people, and the coming fight was growing a clearer picture to their eyes; so from side to side of the river they shouted out the cries of their Houses, or friend called to friend across the eddies of Mirkwood-water, and there was game and glee enough.

So they fared till the wood gave way before them, and lo, the beginning of another plain, somewhat like the Mid-mark. There also the water widened out before them, and there were eyots in it with stony shores crowned with willow or with alder, and aspens rising from the midst of them.

But as for the plain, it was thus much different from Mid-mark, that the wood which begirt it rose on the south into low hills, and away beyond them were other hills blue in the distance, for the most bare of wood, and not right high, the pastures of the wild-bull and the bison, whereas now dwelt a folk somewhat scattered and feeble; hunters and herdsmen, with little tillage about their abodes, a folk akin to the Markmen and allied to them. They had come into those parts later than the Markmen, as the old tales told; which said moreover that in days gone by a folk dwelt among those hills who were alien from the Goths, and great foes to the Markmen; and how that on a time they came down from their hills with a great host, together with new-comers of their own blood, and made their way through the wild-wood, and fell upon the Upper-mark; and how that there befel a fearful battle that endured for three days; and the first day the Aliens worsted the Markmen, who were but a few, since they were they of the Upper-mark only. So the Aliens burned their houses and slew their old men, and drave off many of their women and children; and the remnant of the men of the Upper-mark with all that they had, which was now but little, took refuge in an island of Mirkwood-water, where they fenced themselves as well as they could for that night; for they expected the succour of their kindred of the Mid-mark and the Nether-mark, unto whom they had sped the war-arrow when they first had tidings of the onset of the Aliens.

So at the sun-rising they sacrificed to the Gods twenty chieftains of the Aliens whom they had taken, and therewithal a maiden of their own kindred, the daughter of their war-duke, that she might lead that mighty company to the House of the Gods; and thereto was she nothing loth, but went right willingly.

There then they awaited the onset. But the men of Mid-mark came up in the morning, when the battle was but just joined, and fell on so fiercely that the aliens gave back, and then they of the Upper-mark stormed out of their eyot, and fell on over the ford, and fought till the water ran red with their blood, and the blood of the foemen. So the Aliens gave back before the onset of the Markmen all over the meads; but when they came to the hillocks and the tofts of the half-burned habitations, and the wood was on their flank, they made a stand again, and once more the battle waxed hot, for they were very many, and had many bowmen: there fell the War-duke of the Markmen, whose daughter had been offered up for victory, and his name was Agni, so that the tofts where he fell have since been called Agni’s Tofts. So that day they fought all over the plain, and a great many died, both of the Aliens and the Markmen, and though these last were victorious, yet when the sun went down there still were the Aliens abiding in the Upper-mark, fenced by their wain-burg, beaten, and much diminished in number, but still a host of men: while of the Markmen many had fallen, and many more were hurt, because the Aliens were good bowmen.

But on the morrow again, as the old tale told, came up the men of the Nether-mark fresh and unwounded; and so the battle began again on the southern limit of the Upper-mark where the Aliens had made their wain-burg. But not long did it endure; for the Markmen fell on so fiercely, that they stormed over the wain-burg, and slew all before them, and there was a very great slaughter of the Aliens; so great, tells the old tale, that never again durst they meet the Markmen in war.

Thus went forth the host of the Markmen, faring along both sides of the water into the Upper-mark; and on the west side, where went the Wolfings, the ground now rose by a long slope into a low hill, and when they came unto the brow thereof, they beheld before them the whole plain of the Upper-mark, and the dwellings of the kindred therein all girdled about by the wild-wood; and beyond, the blue hills of the herdsmen, and beyond them still, a long way aloof, lying like a white cloud on the verge of the heavens, the snowy tops of the great mountains. And as they looked down on to the plain they saw it embroidered, as it were, round about the habitations which lay within ken by crowds of many people, and the banners of the kindreds and the arms of men; and many a place they saw named after the ancient battle and that great slaughter of the Aliens.

On their left hand lay the river, and as it now fairly entered with them into the Upper-mark, it spread out into wide rippling shallows beset with yet more sandy eyots, amongst which was one much greater, rising amidmost into a low hill, grassy and bare of tree or bush; and this was the island whereon the Markmen stood on the first day of the Great Battle, and it was now called the Island of the Gods.

Thereby was the ford, which was firm and good and changed little from year to year, so that all Markmen knew it well and it was called Battleford: thereover now crossed all the eastern companies, footmen and horsemen, freemen and thralls, wains and banners, with shouting and laughter, and the noise of horns and the lowing of neat, till all that plain’s end was flooded with the host of the Markmen.

But when the eastern-abiders had crossed, they made no stay, but went duly ordered about their banners, winding on toward the first of the abodes on the western side of the water; because it was but a little way southwest of this that the Thing-stead of the Upper-mark lay; and the whole Folk was summoned thither when war threatened from the South, just as it was called to the Thing-stead of the Nether-mark, when the threat of war came from the North. But the western companies stayed on the brow of that low hill till all the eastern men were over the river, and on their way to the Thing-stead, and then they moved on.

So came the Wolfings and their fellows up to the dwellings of the northernmost kindred, who were called the Daylings, and bore on their banner the image of the rising sun. Thereabout was the Mark somewhat more hilly and broken than in the Mid-mark, so that the Great Roof of the Daylings, which was a very big house, stood on a hillock whose sides had been cleft down sheer on all sides save one (which was left as a bridge) by the labour of men, and it was a very defensible place.

Thereon were now gathered round about the Roof all the stay-at-homes of the kindred, who greeted with joyous cries the men-at-arms as they passed. Albeit one very old man, who sat in a chair near to the edge of the sheer hill looking on the war array, when he saw the Wolfing banner draw near, stood up to gaze on it, and then shook his head sadly, and sank back again into his chair, and covered his face with his hands: and when the folk saw that, a silence bred of the coldness of fear fell on them, for that elder was deemed a foreseeing man.

But as those three fellows, of whose talk of yesterday the tale has told, drew near and beheld what the old carle did (for they were riding together this day also) the Beaming man laid his hand on Wolfkettle’s rein and said:

“Lo you, neighbour, if thy Vala hath seen nought, yet hath this old man seen somewhat, and that somewhat even as the little lad saw it. Many a mother’s son shall fall before the Welshmen.”

But Wolfkettle shook his rein free, and his face reddened as of one who is angry, yet he kept silence, while the Elking said:

“Let be, Toti! for he that lives shall tell the tale to the foreseers, and shall make them wiser than they are to-day.”

Then laughed Toti, as one who would not be thought to be too heedful of the morrow. But Wolfkettle brake out into speech and rhyme, and said:

“O warriors, the Wolfing kindred shall live or it shall die;

And alive it shall be as the oak-tree when the summer storm goes by;

But dead it shall be as its bole, that they hew for the corner-post

Of some fair and mighty folk-hall, and the roof of a war-fain host.”

So therewith they rode their ways past the abode of the Daylings.

Straight to the wood went all the host, and so into it by a wide way cleft through the thicket, and in some thirty minutes they came thereby into a great wood-lawn cleared amidst of it by the work of men’s hands. There already was much of the host gathered, sitting or standing in a great ring round about a space bare of men, where amidmost rose a great mound raised by men’s hands and wrought into steps to be the sitting-places of the chosen elders and chief men of the kindred; and atop the mound was flat and smooth save for a turf bench or seat that went athwart it whereon ten men might sit.

All the wains save the banner-wains had been left behind at the Dayling abode, nor was any beast there save the holy beasts who drew the banner-wains and twenty white horses, that stood wreathed about with flowers within the ring of warriors, and these were for the burnt offering to be given to the Gods for a happy day of battle. Even the war-horses of the host they must leave in the wood without the wood-lawn, and all men were afoot who were there.

For this was the Thing-stead of the Upper-mark, and the holiest place of the Markmen, and no beast, either neat, sheep, or horse might pasture there, but was straightway slain and burned if he wandered there; nor might any man eat therein save at the holy feasts when offerings were made to the Gods.

So the Wolfings took their place there in the ring of men with the Elkings on their right hand and the Beamings on their left. And in the midst of the Wolfing array stood Thiodolf clad in the dwarf-wrought hauberk: but his head was bare; for he had sworn over the Cup of Renown that he would fight unhelmed throughout all that trouble, and would bear no shield in any battle thereof however fierce the onset might be.

Short, and curling close to his head was his black hair, a little grizzled, so that it looked like rings of hard dark iron: his forehead was high and smooth, his lips full and red, his eyes steady and wide-open, and all his face joyous with the thought of the fame of his deeds, and the coming battle with a foeman whom the Markmen knew not yet.

He was tall and wide-shouldered, but so exceeding well fashioned of all his limbs and body that he looked no huge man. He was a man well beloved of women, and children would mostly run to him gladly and play with him. A most fell warrior was he, whose deeds no man of the Mark could equal, but blithe of speech even when he was sorrowful of mood, a man that knew not bitterness of heart: and for all his exceeding might and valiancy, he was proud and high to no man; so that the very thralls loved him.

He was not abounding in words in the field; nor did he use much the custom of those days in reviling and defying with words the foe that was to be smitten with swords.

There were those who had seen him in the field for the first time who deemed him slack at the work: for he would not always press on with the foremost, but would hold him a little aback, and while the battle was young he forbore to smite, and would do nothing but help a kinsman who was hard pressed, or succour the wounded. So that if men were dealing with no very hard matter, and their hearts were high and overweening, he would come home at whiles with unbloodied blade. But no man blamed him save those who knew him not: for his intent was that the younger men should win themselves fame, and so raise their courage, and become high-hearted and stout.

But when the stour was hard, and the battle was broken, and the hearts of men began to fail them, and doubt fell upon the Markmen, then was he another man to see: wise, but swift and dangerous, rushing on as if shot out by some mighty engine: heedful of all, on either side and in front; running hither and thither as the fight failed and the fire of battle faltered; his sword so swift and deadly that it was as if he wielded the very lightening of the heavens: for with the sword it was ever his wont to fight.

But it must be said that when the foemen turned their backs, and the chase began, then Thiodolf would nowise withhold his might as in the early battle, but ever led the chase, and smote on the right hand and on the left, sparing none, and crying out to the men of the kindred not to weary in their work, but to fulfil all the hours of their day.

For thuswise would he say and this was a word of his:

“Let us rest to-morrow, fellows, since to-day we have fought amain!

Let not these men we have smitten come aback on our hands again,

And say ‘Ye Wolfing warriors, ye have done your work but ill,

Fall to now and do it again, like the craftsman who learneth his skill.’”

Such then was Thiodolf, and ever was he the chosen leader of the Wolfings and often the War-duke of the whole Folk.

By his side stood the other chosen leader, whose name was Heriulf; a man well stricken in years, but very mighty and valiant; wise in war and well renowned; of few words save in battle, and therein a singer of songs, a laugher, a joyous man, a merry companion. He was a much bigger man than Thiodolf; and indeed so huge was his stature, that he seemed to be of the kindred of the Mountain Giants; and his bodily might went with his stature, so that no one man might deal with him body to body. His face was big; his cheek-bones high; his nose like an eagle’s neb, his mouth wide, his chin square and big; his eyes light-grey and fierce under shaggy eyebrows: his hair white and long.

Such were his raiment and weapons, that he wore a coat of fence of dark iron scales sewn on to horse-hide, and a dark iron helm fashioned above his brow into the similitude of the Wolf’s head with gaping jaws; and this he had wrought for himself with his own hands, for he was a good smith. A round buckler he bore and a huge twibill, which no man of the kindred could well wield save himself; and it was done both blade and shaft with knots and runes in gold; and he loved that twibill well, and called it the Wolf’s Sister.

There then stood Heriulf, looking no less than one of the forefathers of the kindred come back again to the battle of the Wolfings.

He was well-beloved for his wondrous might, and he was no hard man, though so fell a warrior, and though of few words, as aforesaid, was a blithe companion to old and young. In numberless battles had he fought, and men deemed it a wonder that Odin had not taken to him a man so much after his own heart; and they said it was neighbourly done of the Father of the Slain to forbear his company so long, and showed how well he loved the Wolfing House.

For a good while yet came other bands of Markmen into the Thing-stead; but at last there was an end of their coming. Then the ring of men opened, and ten warriors of the Daylings made their way through it, and one of them, the oldest, bore in his hand the War-horn of the Daylings; for this kindred had charge of the Thing-stead, and of all appertaining to it. So while his nine fellows stood round about the Speech-Hill, the old warrior clomb up to the topmost of it, and blew a blast on the horn. Thereon they who were sitting rose up, and they who were talking each to each held their peace, and the whole ring drew nigher to the hill, so that there was a clear space behind them ’twixt them and the wood, and a space before them between them and the hill, wherein were those nine warriors, and the horses for the burnt-offering, and the altar of the Gods; and now were all well within ear-shot of a man speaking amidst the silence in a clear voice.

But there were gathered of the Markmen to that place some four thousand men, all chosen warriors and doughty men; and of the thralls and aliens dwelling with them they were leading two thousand. But not all of the freemen of the Upper-mark could be at the Thing; for needs must there be some guard to the passes of the wood toward the south and the hills of the herdsmen, whereas it was no wise impassable to a wisely led host: so five hundred men, what of freemen, what of thralls, abode there to guard the wild-wood; and these looked to have some helping from the hill-men.

Now came an ancient warrior into the space between the men and the wild-wood holding in his hand a kindled torch; and first he faced due south by the sun, then, turning, he slowly paced the whole circle going from east to west, and so on till he had reached the place he started from: then he dashed the torch to the ground and quenched the fire, and so went his ways to his own company again.

Then the old Dayling warrior on the mound-top drew his sword, and waved it flashing in the sun toward the four quarters of the heavens; and thereafter blew again a blast on the War-horn. Then fell utter silence on the whole assembly, and the wood was still around them, save here and there the stamping of a war-horse or the sound of his tugging at the woodland grass; for there was little resort of birds to the depths of the thicket, and the summer morning was windless.

CHAPTER VIII—THE FOLK-MOTE OF THE MARKMEN

So the Dayling warrior lifted up his voice and said:

“O kindreds of the Markmen, hearken the words I say;

For no chancehap assembly is gathered here to-day.

The fire hath gone around us in the hands of our very kin,

And twice the horn hath sounded, and the Thing is hallowed in.

Will ye hear or forbear to hearken the tale there is to tell?

There are many mouths to tell it, and a many know it well.

And the tale is this, that the foemen against our kindreds fare

Who eat the meadows desert, and burn the desert bare.”

Then sat he down on the turf seat; but there arose a murmur in the assembly as of men eager to hearken; and without more ado came a man out of a company of the Upper-mark, and clomb up to the top of the Speech-Hill, and spoke in a loud voice:

“I am Bork, a man of the Geirings of the Upper-mark: two days ago I and five others were in the wild-wood a-hunting, and we wended through the thicket, and came into the land of the hill-folk; and after we had gone a while we came to a long dale with a brook running through it, and yew-trees scattered about it and a hazel copse at one end; and by the copse was a band of men who had women and children with them, and a few neat, and fewer horses; but sheep were feeding up and down the dale; and they had made them booths of turf and boughs, and were making ready their cooking fires, for it was evening. So when they saw us, they ran to their arms, but we cried out to them in the tongue of the Goths and bade them peace. Then they came up the bent to us and spake to us in the Gothic tongue, albeit a little diversely from us; and when we had told them what and whence we were, they were glad of us, and bade us to them, and we went, and they entreated us kindly, and made us such cheer as they might, and gave us mutton to eat, and we gave them venison of the wild-wood which we had taken, and we abode with them there that night.