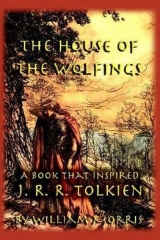

Текст книги "The House of the Wolfings"

Автор книги: William Morris

Жанры:

Историческое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Thus these poor people thought of the Gods whom they worshipped, and the friends whom they loved, and could not choose but be heavy-hearted when they thought that the wild-wood was awaiting them to swallow all up, and take away from them their Gods and their friends and the mirth of their life, and burden them with hunger and thirst and weariness, that their children might begin once more to build the House and establish the dwelling, and call new places by old names, and worship new Gods with the ancient worship.

Such imaginations of trouble then were in the hearts of the stay-at-homes of the Wolfings; the tale tells not indeed that all had such forebodings, but chiefly the old folk who were nursing the end of their life-days amidst the cherishing Kindred of the House.

But now they were beginning to turn them back again to the habitations, and a thin stream was flowing through the acres, when they heard a confused sound drawing near blended of horns and the lowing of beasts and the shouting of men; and they looked and saw a throng of brightly clad men coming up stream alongside of Mirkwood-water; and they were not afraid, for they knew that it must be some other company of the Markmen journeying to the hosting of the Folk: and presently they saw that it was the House of the Beamings following their banner on the way to the Thing-stead. But when the new-comers saw the throng out in the meads, some of their young men pricked on their horses and galloped on past the women and old men, to whom they threw a greeting, as they ran past to catch up with the bands of the Wolfings; for between the two houses was there affinity, and much good liking lay between them; and the stay-at-homes, many of them, lingered yet till the main body of the Beamings came with their banner: and their array was much like to that of the Wolfings, but gayer; for whereas it pleased the latter to darken all their war-gear to the colour of the grey Wolf, the Beamings polished all their gear as bright as might be, and their raiment also was mostly bright green of hue and much beflowered; and the sign on their banner was a green leafy tree, and the wain was drawn by great white bulls.

So when their company drew anear to the throng of the stay-at-homes they went to meet and greet each other, and tell tidings to each other; but their banner held steadily onward amidst their converse, and in a little while they followed it, for the way was long to the Thing-stead of the Upper-mark.

So passed away the fighting men by the side of Mirkwood-water, and the throng of the stay-at-homes melted slowly from the meadow and trickled along through the acres to the habitations of the Wolfings, and there they fell to doing whatso of work or play came to their hands.

CHAPTER V—CONCERNING THE HALL-SUN

When the warriors and the others had gone down to the mead, the Hall-Sun was left standing on the Hill of Speech, and she stood there till she saw the host in due array going on its ways dark and bright and beautiful; then she made as if to turn aback to the Great Roof; but all at once it seemed to her as if something held her back, as if her will to move had departed from her, and that she could not put one foot before the other. So she lingered on the Hill, and the quenched candle fell from her hand, and presently she sank adown on the grass and sat there with the face of one thinking intently. Yet was it with her that a thousand thoughts were in her mind at once and no one of them uppermost, and images of what had been and what then was flickered about in her brain, and betwixt them were engendered images of things to be, but unstable and not to be trowed in. So sat the Hall-Sun on the Hill of Speech lost in a dream of the day, whose stories were as little clear as those of a night-dream.

But as she sat musing thus, came to her a woman exceeding old to look on, whom she knew not as one of the kindred or a thrall; and this carline greeted her by the name of Hall-Sun and said:

“Hail, Hall-Sun of the Markmen! how fares it now with thee

When the whelps of the Woodbeast wander with the Leafage of the Tree

All up the Mirkwood-water to seek what they shall find,

The oak-boles of the battle and the war-wood stark and blind?”

Then answered the maiden:

“It fares with me, O mother, that my soul would fain go forth

To behold the ways of the battle, and the praise of the warriors’ worth.

But yet is it held entangled in a maze of many a thing,

As the low-grown bramble holdeth the brake-shoots of the Spring.

I think of the thing that hath been, but no shape is in my thought;

I think of the day that passeth, and its story comes to nought.

I think of the days that shall be, nor shape I any tale.

I will hearken thee, O mother, if hearkening may avail.”

The Carline gazed at her with dark eyes that shone brightly from amidst her brown wrinkled face: then she sat herself down beside her and spake:

“From a far folk have I wandered and I come of an alien blood,

But I know all tales of the Wolfings and their evil and their good;

And when I heard of thy fairness, thereof I heard it said,

That for thee should be never a bridal nor a place in the warrior’s bed.”

The maiden neither reddened nor paled, but looking with calm steady eyes into the Carline’s face she answered:

“Yea true it is, I am wedded to the mighty ones of old,

And the fathers of the Wolfings ere the days of field and fold.”

Then a smile came into the eyes of the old woman and she said.

“How glad shall be thy mother of thy worship and thy worth,

And the father that begat thee if yet they dwell on earth!”

But the Hall-Sun answered in the same steady manner as before:

“None knoweth who is my mother, nor my very father’s name;

But when to the House of the Wolfings a wild-wood waif I came,

They gave me a foster-mother an ancient dame and good,

And a glorious foster-father the best of all the blood.”

Spake the Carline.

“Yea, I have heard the story, but scarce therein might I trow

That thou with all thy beauty wert born ’neath the oaken bough,

And hast crawled a naked baby o’er the rain-drenched autumn-grass;

Wilt thou tell the wandering woman what wise it cometh to pass

That thou art the Mid-mark’s Hall-Sun, and the sign of the Wolfings’ gain?

Thou shalt pleasure me much by the telling, and there of shalt thou be fain.”

Then answered the Hall-Sun.

“Yea; thus much I remember for the first of my memories;

That I lay on the grass in the morning and above were the boughs of the trees.

But nought naked was I as the wood-whelp, but clad in linen white,

And adown the glades of the oakwood the morning sun lay bright.

Then a hind came out of the thicket and stood on the sunlit glade,

And turned her head toward the oak tree and a step on toward me made.

Then stopped, and bounded aback, and away as if in fear,

That I saw her no more; then I wondered, though sitting close anear

Was a she-wolf great and grisly. But with her was I wont to play,

And pull her ears, and belabour her rugged sides and grey,

And hold her jaws together, while she whimpered, slobbering

For the love of my love; and nowise I deemed her a fearsome thing.

There she sat as though she were watching, and o’er head a blue-winged jay

Shrieked out from the topmost oak-twigs, and a squirrel ran his way

Two tree-trunks off. But the she-wolf arose up suddenly

And growled with her neck-fell bristling, as if danger drew anigh;

And therewith I heard a footstep, for nice was my ear to catch

All the noises of the wild-wood; so there did we sit at watch

While the sound of feet grew nigher: then I clapped hand on hand

And crowed for joy and gladness, for there out in the sun did stand

A man, a glorious creature with a gleaming helm on his head,

And gold rings on his arms, in raiment gold-broidered crimson-red.

Straightway he strode up toward us nor heeded the wolf of the wood

But sang as he went in the oak-glade, as a man whose thought is good,

And nought she heeded the warrior, but tame as a sheep was grown,

And trotted away through the wild-wood with her crest all laid adown.

Then came the man and sat down by the oak-bole close unto me

And took me up nought fearful and set me on his knee.

And his face was kind and lovely, so my cheek to his cheek I laid

And touched his cold bright war-helm and with his gold rings played,

And hearkened his words, though I knew not what tale they had to tell,

Yet fain was my heart of their music, and meseemed I loved him well.

So we fared for a while and were fain, till he set down my feet on the grass,

And kissed me and stood up himself, and away through the wood did he pass.

And then came back the she-wolf and with her I played and was fain.

Lo the first thing I remember: wilt thou have me babble again?”

Spake the Carline and her face was soft and kind:

“Nay damsel, long would I hearken to thy voice this summer day.

But how didst thou leave the wild-wood, what people brought thee away?”

Then said the Hall-Sun:

“I awoke on a time in the even, and voices I heard as I woke;

And there was I in the wild-wood by the bole of the ancient oak,

And a ring of men was around me, and glad was I indeed

As I looked upon their faces and the fashion of their weed.

For I gazed on the red and the scarlet and the beaten silver and gold,

And blithe were their noble faces and kindly to behold,

And nought had I seen of such-like since that hour of the other day

When that warrior came to the oak glade with the little child to play.

And forth now he came, with the face that my hands had fondled before,

And a battle shield wrought fairly upon his arm he bore,

And thereon the wood-wolf’s image in ruddy gold was done.

Then I stretched out my little arms towards the glorious shining one

And he took me up and set me on his shoulder for a while

And turned about to his fellows with a blithe and joyous smile;

And they shouted aloud about me and drew forth gleaming swords

And clashed them on their bucklers; but nought I knew of the words

Of their shouting and rejoicing. So thereafter was I laid

And borne forth on the warrior’s warshield, and our way through the wood we made

’Midst the mirth and great contentment of those fair-clad shielded men.

“But no tale of the wolf and the wild-wood abides with me since then,

And the next thing I remember is a huge and dusky hall,

A world for my little body from ancient wall to wall;

A world of many doings, and nought for me to do,

A world of many noises, and known to me were few.

“Time wore, and I spoke with the Wolfings and knew the speech of the kin,

And was strange ’neath the roof no longer, as a lonely waif therein;

And I wrought as a child with my playmates and every hour looked on

Unto the next hour’s joyance till the happy day was done.

And going and coming amidst us was a woman tall and thin

With hair like the hoary barley and silver streaks therein.

And kind and sad of visage, as now I remember me,

And she sat and told us stories when we were aweary with glee,

And many of us she fondled, but me the most of all.

And once from my sleep she waked me and bore me down the hall,

In the hush of the very midnight, and I was feared thereat.

But she brought me unto the dais, and there the warrior sat,

Who took me up and kissed me, as erst within the wood;

And meseems in his arms I slumbered: but I wakened again and stood

Alone with the kindly woman, and gone was the goodly man,

And athwart the hush of the Folk-hall the moon shone bright and wan,

And the woman dealt with a lamp hung up by a chain aloft,

And she trimmed it and fed it with oil, while she chanted sweet and soft

A song whose words I knew not: then she ran it up again,

And up in the darkness above us died the length of its wavering chain.”

“Yea,” said the carline, “this woman will have been the Hall-Sun that came before thee. What next dost thou remember?”

Said the maiden:

“Next I mind me of the hazels behind the People’s Roof,

And the children running thither and the magpie flitting aloof,

And my hand in the hand of the Hall-Sun, as after the others we went,

And she soberly hearkening my prattle and the words of my intent.

And now would I call her ‘Mother,’ and indeed I loved her well.

“So I waxed; and now of my memories the tale were long to tell;

But as the days passed over, and I fared to field and wood,

Alone or with my playmates, still the days were fair and good.

But the sad and kindly Hall-Sun for my fosterer now I knew,

And the great and glorious warrior that my heart clung sorely to

Was but my foster-father; and I knew that I had no kin

In the ancient House of the Wolfings, though love was warm therein.”

Then smiled the carline and said: “Yea, he is thy foster-father, and yet a fond one.”

“Sooth is that,” said the Hall-Sun. “But wise art thou by seeming. Hast thou come to tell me of what kindred I am, and who is my father and who is my mother?”

Said the carline: “Art thou not also wise? Is it not so that the Hall-Sun of the Wolfings seeth things that are to come?”

“Yea,” she said, “yet have I seen waking or sleeping no other father save my foster-father; yet my very mother I have seen, as one who should meet her in the flesh one day.”

“And good is that,” said the carline; and as she spoke her face waxed kinder, and she said:

“Tell us more of thy days in the House of the Wolfings and how thou faredst there.”

Said the Hall-Sun:

“I waxed ’neath the Roof of the Wolfings, till now to look upon

I was of sixteen winters, and the love of the Folk I won,

And in lovely weed they clad me like the image of a God:

And lonely now full often the wild-wood ways I trod,

And I feared no wild-wood creature, and my presence scared them nought;

And I fell to know of wisdom, and within me stirred my thought,

So that oft anights would I wander through the mead and far away,

And swim the Mirkwood-water, and amidst his eddies play

When earth was dark in the dawn-tide; and over all the folk

I knew of the beasts’ desires, as though in words they spoke.

“So I saw of things that should be, were they mighty things or small,

And upon a day as it happened came the war-word to the hall,

And the House must wend to the warfield, and as they sang, and played

With the strings of the harp that even, and the mirth of the war-eve made,

Came the sight of the field to my eyes, and the words waxed hot in me,

And I needs must show the picture of the end of the fight to be.

Then I showed them the Red Wolf bristling o’er the broken fleeing foe;

And the war-gear of the fleers, and their banner did I show,

To wit the Ling-worm’s image with the maiden in his mouth;

There I saw my foster-father ’mid the pale blades of the South,

Till aloof swept all the handplay and the hurry of the chase,

And he lay along by an ash-tree, no helm about his face,

No byrny on his body; and an arrow in his thigh,

And a broken spear in his shoulder. Then I saw myself draw nigh

To sing the song blood-staying. Then saw I how we twain

Went ’midst of the host triumphant in the Wolfings’ banner-wain,

The black bulls lowing before us athwart the warriors’ song,

As up from Mirkwood-water we went our ways along

To the Great Roof of the Wolfings, whence streamed the women out

And the sound of their rejoicing blent with the warriors’ shout.

“They heard me and saw the picture, and they wotted how wise I was grown,

And they loved me, and glad were their hearts at the tale my lips had shown;

And my body clad as an image of a God to the field they bore,

And I held by the mast of the banner as I looked upon their war,

And endured to see unblenching on the wind-swept sunny plain

All the picture of my vision by the men-folk done again.

And over my Foster-father I sang the staunching-song,

Till the life-blood that was ebbing flowed back to his heart the strong,

And we wended back in the war-wain ’midst the gleanings of the fight

Unto the ancient dwelling and the Hall-Sun’s glimmering light.

“So from that day henceforward folk hung upon my words,

For the battle of the autumn, and the harvest of the swords;

And e’en more was I loved than aforetime. So wore a year away,

And heavy was the burden of the lore that on me lay.

“But my fosterer the Hall-Sun took sick at the birth of the year,

And changed her life as the year changed, as summer drew anear.

But she knew that her life was waning, and lying in her bed

She taught me the lore of the Hall-Sun, and every word to be said

At the trimming in the midnight and the feeding in the morn,

And she laid her hands upon me ere unto the howe she was borne

With the kindred gathered about us; and they wotted her weird and her will,

And hailed me for the Hall-Sun when at last she lay there still.

And they did on me the garment, the holy cloth of old,

And the neck-chain wrought for the goddess, and the rings of the hallowed gold.

So here am I abiding, and of things to be I tell,

Yet know not what shall befall me nor why with the Wolfings I dwell.”

Then said the carline:

“What seest thou, O daughter, of the journey of to-day?

And why wendest thou not with the war-host on the battle-echoing way?”

Said the Hall-Sun.

“O mother, here dwelleth the Hall-Sun while the kin hath a dwelling-place,

Nor ever again shall I look on the onset or the chase,

Till the day when the Roof of the Wolfings looketh down on the girdle of foes,

And the arrow singeth over the grass of the kindred’s close;

Till the pillars shake with the shouting and quivers the roof-tree dear,

When the Hall of the Wolfings garners the harvest of the spear.”

Therewith she stood on her feet and turned her face to the Great Roof, and gazed long at it, not heeding the crone by her side; and she muttered words of whose signification the other knew not, though she listened intently, and gazed ever at her as closely as might be.

Then fell the Hall-Sun utterly silent, and the lids closed over her eyes, and her hands were clenched, and her feet pressed hard on the daisies: her bosom heaved with sore sighs, and great tear-drops oozed from under her eyelids and fell on to her raiment and her feet and on to the flowery summer grass; and at the last her mouth opened and she spake, but in a voice that was marvellously changed from that she spake in before:

“Why went ye forth, O Wolfings, from the garth your fathers built,

And the House where sorrow dieth, and all unloosed is guilt?

Turn back, turn back, and behold it! lest your feet be over slow

When your shields are heavy-burdened with the arrows of the foe;

How ye totter, how ye stumble on the rough and corpse-strewn way!

And lo, how the eve is eating the afternoon of day!

O why are ye abiding till the sun is sunk in night

And the forest trees are ruddy with the battle-kindled light?

O rest not yet, ye Wolfings, lest void be your resting-place,

And into lands that ye know not the Wolf must turn his face,

And ye wander and ye wander till the land in the ocean cease,

And your battle bring no safety and your labour no increase.”

Then was she silent for a while, and her tears ceased to flow; but presently her eyes opened once more, and she lifted up her voice and cried aloud—

“I see, I see! O Godfolk behold it from aloof,

How the little flames steal flickering along the ridge of the Roof!

They are small and red ’gainst the heavens in the summer afternoon;

But when the day is dusking, white, high shall they wave to the moon.

Lo, the fire plays now on the windows like strips of scarlet cloth

Wind-waved! but look in the night-tide on the onset of its wrath,

How it wraps round the ancient timbers and hides the mighty roof

But lighteth little crannies, so lost and far aloof,

That no man yet of the kindred hath seen them ere to-night,

Since first the builder builded in loving and delight!”

Then again she stayed her speech with weeping and sobbing, but after a while was still again, and then she spoke pointing toward the roof with her right hand.

“I see the fire-raisers and iron-helmed they are,

Brown-faced about the banners that their hands have borne afar.

And who in the garth of the kindred shall bear adown their shield

Since the onrush of the Wolfings they caught in the open field,

As the might of the mountain lion falls dead in the hempen net?

O Wolfings, long have ye tarried, but the hour abideth yet.

What life for the life of the people shall be given once for all,

What sorrow shall stay sorrow in the half-burnt Wolfing Hall?

There is nought shall quench the fire save the tears of the Godfolk’s kin,

And the heart of the life-delighter, and the life-blood cast therein.”

Then once again she fell silent, and her eyes closed again, and the slow tears gushed out from them, and she sank down sobbing on the grass, and little by little the storm of grief sank and her head fell back, and she was as one quietly asleep. Then the carline hung over her and kissed her and embraced her; and then through her closed eyes and her slumber did the Hall-Sun see a marvel; for she who was kissing her was young in semblance and unwrinkled, and lovely to look on, with plenteous long hair of the hue of ripe barley, and clad in glistening raiment such as has been woven in no loom on earth.

And indeed it was the Wood-Sun in the semblance of a crone, who had come to gather wisdom of the coming time from the foreseeing of the Hall-Sun; since now at last she herself foresaw nothing of it, though she was of the kindred of the Gods and the Fathers of the Goths. So when she had heard the Hall-Sun she deemed that she knew but too well what her words meant, and what for love, what for sorrow, she grew sick at heart as she heard them.

So at last she arose and turned to look at the Great Roof; and strong and straight, and cool and dark grey showed its ridge against the pale sky of the summer afternoon all quivering with the heat of many hours’ sun: dark showed its windows as she gazed on it, and stark and stiff she knew were its pillars within.

Then she said aloud, but to herself: “What then if a merry and mighty life be given for it, and the sorrow of the people be redeemed; yet will not I give the life which is his; nay rather let him give the bliss which is mine. But oh! how may it be that he shall die joyous and I shall live unhappy!”

Then she went slowly down from the Hill of Speech, and whoso saw her deemed her but a gangrel carline. So she went her ways and let the wood cover her.

But in a little while the Hall-Sun awoke alone, and sat up with a sigh, and she remembered nothing concerning her sight of the flickering flame along the hall-roof, and the fire-tongues like strips of scarlet cloth blown by the wind, nor had she any memory of her words concerning the coming day. But the rest of her talk with the carline she remembered, and also the vision of the beautiful woman who had kissed and embraced her; and she knew that it was her very mother. Also she perceived that she had been weeping, therefore she knew that she had uttered words of wisdom. For so it fared with her at whiles, that she knew not her own words of foretelling, but spoke them out as if in a dream.

So now she went down from the Hill of Speech soberly, and turned toward the Woman’s door of the hall, and on her way she met the women and old men and youths coming back from the meadow with little mirth: and there were many of them who looked shyly at her as though they would gladly have asked her somewhat, and yet durst not. But for her, her sadness passed away when she came among them, and she looked kindly on this and that one of them, and entered with them into the Woman’s Chamber, and did what came to her hand to do.

CHAPTER VI—THEY TALK ON THE WAY TO THE FOLK-THING

All day long one standing on the Speech-hill of the Wolfings might have seen men in their war-array streaming along the side of Mirkwood-water, on both sides thereof; and the last comers from the Nether-mark came hastening all they might; for they would not be late at the trysting-place. But these were of a kindred called the Laxings, who bore a salmon on their banner; and they were somewhat few in number, for they had but of late years become a House of the Markmen. Their banner-wain was drawn by white horses, fleet and strong, and they were no great band, for they had but few thralls with them, and all, free men and thralls, were a-horseback; so they rode by hastily with their banner-wain, their few munition-wains following as they might.

Now tells the tale of the men-at-arms of the Wolfings and the Beamings, that soon they fell in with the Elking host, which was journeying but leisurely, so that the Wolfings might catch up with them: they were a very great kindred, the most numerous of all Mid-mark, and at this time they had affinity with the Wolfings. But old men of the House remembered how they had heard their grandsires and very old men tell that there had been a time when the Elking House had been established by men from out of the Wolfing kindred, and how they had wandered away from the Mark in the days when it had been first settled, and had abided aloof for many generations of men; and so at last had come back again to the Mark, and had taken up their habitation at a place in Mid-mark where was dwelling but a remnant of a House called the Thyrings, who had once been exceeding mighty, but had by that time almost utterly perished in a great sickness which befel in those days. So then these two Houses, the wanderers come back and the remnant left by the sickness of the Gods, made one House together, and increased and throve after their coming together, and wedded with the Wolfings, and became a very great House.

Gallant and glorious was their array now, as they marched along with their banner of the Elk, which was drawn by the very beasts themselves tamed to draught to that end through many generations; they were fatter and sleeker than their wild-wood brethren, but not so mighty.

So were the men of the three kindreds somewhat mingled together on the way. The Wolfings were the tallest and the biggest made; but of those dark-haired men aforesaid, were there fewest amongst the Beamings, and most among the Elkings, as though they had drawn to them more men of alien blood during their wanderings aforesaid. So they talked together and made each other good cheer, as is the wont of companions in arms on the eve of battle; and the talk ran, as may be deemed, on that journey and what was likely to come of it: and spake an Elking warrior to a Wolfing by whom he rode:

“O Wolfkettle, hath the Hall-Sun had any foresight of the day of battle?”

“Nay,” said the other, “when she lighted the farewell candle, she bade us come back again, and spoke of the day of our return; but that methinks, as thou and I would talk of it, thinking what would be likely to befal. Since we are a great host of valiant men, and these Welshmen '7b2'7d most valiant, and as the rumour runneth bigger-bodied men than the Hun-folk, and so well ordered as never folk have been. So then if we overthrow them we shall come back again; and if they overthrow us, the remnant of us shall fall back before them till we come to our habitations; for it is not to be looked for that they will fall in upon our rear and prevent us, since we have the thicket of the wild-wood on our flanks.”

“Sooth is that,” said the Elking; “and as to the mightiness of this folk and their customs, ye may gather somewhat from the songs which our House yet singeth, and which ye have heard wide about in the Mark; for this is the same folk of which a many of them tell, making up that story-lay which is called the South-Welsh Lay; which telleth how we have met this folk in times past when we were in fellowship with a folk of the Welsh of like customs to ourselves: for we of the Elkings were then but a feeble folk. So we marched with this folk of the Kymry and met the men of the cities, and whiles we overthrew and whiles were overthrown, but at last in a great battle were overthrown with so great a slaughter, that the red blood rose over the wheels of the wains, and the city-folk fainted with the work of the slaughter, as men who mow a match in the meadows when the swathes are dry and heavy and the afternoon of midsummer is hot; and there they stood and stared on the field of the slain, and knew not whether they were in Home or Hell, so fierce the fight had been.”

Therewith a man of the Beamings, who was riding on the other side of the Elking, reached out over his horse’s neck and said:

“Yea friend, but is there not some telling of a tale concerning how ye and your fellowship took the great city of the Welshmen of the South, and dwelt there long.”

“Yea,” said the Elking, “Hearken how it is told in the South-Welsh Lay:

“‘Have ye not heard

Of the ways of Weird?

How the folk fared forth

Far away from the North?

And as light as one wendeth

Whereas the wood endeth,

When of nought is our need,

And none telleth our deed,

So Rodgeir unwearied and Reidfari wan

The town where none tarried the shield-shaking man.

All lonely the street there, and void was the way

And nought hindered our feet but the dead men that lay

Under shield in the lanes of the houses heavens-high,

All the ring-bearing swains that abode there to die.’

“Tells the Lay, that none abode the Goths and their fellowship, but such as were mighty enough to fall before them, and the rest, both man and woman, fled away before our folk and before the folk of the Kymry, and left their town for us to dwell in; as saith the Lay:

“‘Glistening of gold

Did men’s eyen behold;

Shook the pale sword

O’er the unspoken word,

No man drew nigh us

With weapon to try us,

For the Welsh-wrought shield

Lay low on the field.

By man’s hand unbuilded all seemed there to be,

The walls ruddy gilded, the pearls of the sea:

Yea all things were dead there save pillar and wall,

But they lived and they said us the song of the hall;

The dear hall left to perish by men of the land,