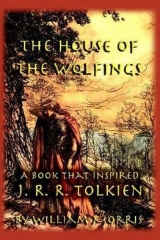

Текст книги "The House of the Wolfings"

Автор книги: William Morris

Жанры:

Историческое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Therewith he laughed out amid the wild-wood, and his speech became song, and he said:

“We wrought in the ring of the hazels, and the wine of war we drank:

From the tide when the sun stood highest to the hour wherein she sank:

And three kings came against me, the mightiest of the Huns,

The evil-eyed in battle, the swift-foot wily ones;

And they gnashed their teeth against me, and they gnawed on the shield-rims there,

On that afternoon of summer, in the high-tide of the year.

Keen-eyed I gazed about me, and I saw the clouds draw up

Till the heavens were dark as the hollow of a wine-stained iron cup,

And the wild-deer lay unfeeding on the grass of the forest glades,

And all earth was scared with the thunder above our clashing blades.

“Then sank a King before me, and on fell the other twain,

And I tossed up the reddened sword-blade in the gathered rush of the rain

And the blood and the water blended, and fragrant grew the earth.

“There long I turned and twisted within the battle-girth

Before those bears of onset: while out from the grey world streamed

The broad red lash of the lightening and in our byrnies gleamed.

And long I leapt and laboured in that garland of the fight

’Mid the blue blades and the lightening; but ere the sky grew light

The second of the Hun-kings on the rain-drenched daisies lay;

And we twain with the battle blinded a little while made stay,

And leaning on our sword-hilts each on the other gazed.

“Then the rain grew less, and one corner of the veil of clouds was raised,

And as from the broidered covering gleams out the shoulder white

Of the bed-mate of the warrior when on his wedding night

He layeth his hand to the linen; so, down there in the west

Gleamed out the naked heaven: but the wrath rose up in my breast,

And the sword in my hand rose with it, and I leaped and hewed at the Hun;

And from him too flared the war-flame, and the blades danced bright in the sun

Come back to the earth for a little before the ending of day.

“There then with all that was in him did the Hun play out the play,

Till he fell, and left me tottering, and I turned my feet to wend

To the place of the mound of the mighty, the gate of the way without end.

And there thou wert. How was it, thou Chooser of the Slain,

Did I die in thine arms, and thereafter did thy mouth-kiss wake me again?”

Ere the last sound of his voice was done she turned and kissed him; and then she said; “Never hadst thou a fear and thine heart is full of hardihood.”

Then he said:

“’Tis the hardy heart, beloved, that keepeth me alive,

As the king-leek in the garden by the rain and the sun doth thrive,

So I thrive by the praise of the people; it is blent with my drink and my meat;

As I slumber in the night-tide it laps me soft and sweet;

And through the chamber window when I waken in the morn

With the wind of the sun’s arising from the meadow is it borne

And biddeth me remember that yet I live on earth:

Then I rise and my might is with me, and fills my heart with mirth,

As I think of the praise of the people; and all this joy I win

By the deeds that my heart commandeth and the hope that lieth therein.”

“Yea,” she said, “but day runneth ever on the heels of day, and there are many and many days; and betwixt them do they carry eld.”

“Yet art thou no older than in days bygone,” said he. “Is it so, O Daughter of the Gods, that thou wert never born, but wert from before the framing of the mountains, from the beginning of all things?”

But she said:

“Nay, nay; I began, I was born; although it may be indeed

That not on the hills of the earth I sprang from the godhead’s seed.

And e’en as my birth and my waxing shall be my waning and end.

But thou on many an errand, to many a field dost wend

Where the bow at adventure bended, or the fleeing dastard’s spear

Oft lulleth the mirth of the mighty. Now me thou dost not fear,

Yet fear with me, beloved, for the mighty Maid I fear;

And Doom is her name, and full often she maketh me afraid

And even now meseemeth on my life her hand is laid.”

But he laughed and said:

“In what land is she abiding? Is she near or far away?

Will she draw up close beside me in the press of the battle play?

And if then I may not smite her ’midst the warriors of the field

With the pale blade of my fathers, will she bide the shove of my shield?”

But sadly she sang in answer:

“In many a stead Doom dwelleth, nor sleepeth day nor night:

The rim of the bowl she kisseth, and beareth the chambering light

When the kings of men wend happy to the bride-bed from the board.

It is little to say that she wendeth the edge of the grinded sword,

When about the house half builded she hangeth many a day;

The ship from the strand she shoveth, and on his wonted way

By the mountain-hunter fareth where his foot ne’er failed before:

She is where the high bank crumbles at last on the river’s shore:

The mower’s scythe she whetteth; and lulleth the shepherd to sleep

Where the deadly ling-worm wakeneth in the desert of the sheep.

Now we that come of the God-kin of her redes for ourselves we wot,

But her will with the lives of men-folk and their ending know we not.

So therefore I bid thee not fear for thyself of Doom and her deed,

But for me: and I bid thee hearken to the helping of my need.

Or else—Art thou happy in life, or lusteth thou to die

In the flower of thy days, when thy glory and thy longing bloom on high?”

But Thiodolf answered her:

“I have deemed, and long have I deemed that this is my second life,

That my first one waned with my wounding when thou cam’st to the ring of strife.

For when in thine arms I wakened on the hazelled field of yore,

Meseemed I had newly arisen to a world I knew no more,

So much had all things brightened on that dewy dawn of day.

It was dark dull death that I looked for when my thought had died away.

It was lovely life that I woke to; and from that day henceforth

My joy of the life of man-folk was manifolded of worth.

Far fairer the fields of the morning than I had known them erst,

And the acres where I wended, and the corn with its half-slaked thirst;

And the noble Roof of the Wolfings, and the hawks that sat thereon;

And the bodies of my kindred whose deliverance I had won;

And the glimmering of the Hall-Sun in the dusky house of old;

And my name in the mouth of the maidens, and the praises of the bold,

As I sat in my battle-raiment, and the ruddy spear well steeled

Leaned ’gainst my side war-battered, and the wounds thine hand had healed.

Yea, from that morn thenceforward has my life been good indeed,

The gain of to-day was goodly, and good to-morrow’s need,

And good the whirl of the battle, and the broil I wielded there,

Till I fashioned the ordered onset, and the unhoped victory fair.

And good were the days thereafter of utter deedless rest

And the prattle of thy daughter, and her hands on my unmailed breast.

Ah good is the life thou hast given, the life that mine hands have won.

And where shall be the ending till the world is all undone?

Here sit we twain together, and both we in Godhead clad,

We twain of the Wolfing kindred, and each of the other glad.”

But she answered, and her face grew darker withal:

“O mighty man and joyous, art thou of the Wolfing kin?

’Twas no evil deed when we mingled, nor lieth doom therein.

Thou lovely man, thou black-haired, thou shalt die and have done no ill.

Fame-crowned are the deeds of thy doing, and the mouths of men they fill.

Thou betterer of the Godfolk, enduring is thy fame:

Yet as a painted image of a dream is thy dreaded name.

Of an alien folk thou comest, that we twain might be one indeed.

Thou shalt die one day. So hearken, to help me at my need.”

His face grew troubled and he said: “What is this word that I am no chief of the Wolfings?”

“Nay,” she said, “but better than they. Look thou on the face of our daughter the Hall-Sun, thy daughter and mine: favoureth she at all of me?”

He laughed: “Yea, whereas she is fair, but not otherwise. This is a hard saying, that I dwell among an alien kindred, and it wotteth not thereof. Why hast thou not told me hereof before?”

She said: “It needed not to tell thee because thy day was waxing, as now it waneth. Once more I bid thee hearken and do my bidding though it be hard to thee.”

He answered: “Even so will I as much as I may; and thus wise must thou look upon it, that I love life, and fear not death.”

Then she spake, and again her words fell into rhyme:

“In forty fights hast thou foughten, and been worsted but in four;

And I looked on and was merry; and ever more and more

Wert thou dear to the heart of the Wood-Sun, and the Chooser of the Slain.

But now whereas ye are wending with slaughter-herd and wain

To meet a folk that ye know not, a wonder, a peerless foe,

I fear for thy glory’s waning, and I see thee lying alow.”

Then he brake in: “Herein is little shame to be worsted by the might of the mightiest: if this so mighty folk sheareth a limb off the tree of my fame, yet shall it wax again.”

But she sang:

“In forty fights hast thou foughten, and beside thee who but I

Beheld the wind-tossed banners, and saw the aspen fly?

But to-day to thy war I wend not, for Weird withholdeth me

And sore my heart forebodeth for the battle that shall be.

To-day with thee I wend not; so I feared, and lo my feet,

That are wont to the woodland girdle of the acres of the wheat,

For thee among strange people and the foeman’s throng have trod,

And I tell thee their banner of battle is a wise and a mighty God.

For these are the folk of the cities, and in wondrous wise they dwell

’Mid confusion of heaped houses, dim and black as the face of hell;

Though therefrom rise roofs most goodly, where their captains and their kings

Dwell amidst the walls of marble in abundance of fair things;

And ’mid these, nor worser nor better, but builded otherwise

Stand the Houses of the Fathers, and the hidden mysteries.

And as close as are the tree-trunks that within the beech-wood thrive

E’en so many are their pillars; and therein like men alive

Stand the images of god-folk in such raiment as they wore

In the years before the cities and the hidden days of yore.

Ah for the gold that I gazed on! and their store of battle gear,

And strange engines that I knew not, or the end for which they were.

Ah for the ordered wisdom of the war-array of these,

And the folks that are sitting about them in dumb down-trodden peace!

So I thought now fareth war-ward my well-beloved friend,

And the weird of the Gods hath doomed it that no more with him may I wend!

Woe’s me for the war of the Wolfings wherefrom I am sundered apart,

And the fruitless death of the war-wise, and the doom of the hardy heart!”

Then he answered, and his eyes grew kind as he looked on her:

“For thy fair love I thank thee, and thy faithful word, O friend!

But how might it otherwise happen but we twain must meet in the end,

The God of this mighty people and the Markmen and their kin?

Lo, this is the weird of the world, and what may we do herein?”

Then mirth came into her face again as she said:

“Who wotteth of Weird, and what she is till the weird is accomplished? Long hath it been my weird to love thee and to fashion deeds for thee as I may; nor will I depart from it now.” And she sang:

“Keen-edged is the sword of the city, and bitter is its spear,

But thy breast in the battle, beloved, hath a wall of the stithy’s gear.

What now is thy wont in the handplay with the helm and the hauberk of rings?

Farest thou as the thrall and the cot-carle, or clad in the raiment of kings?”

He started, and his face reddened as he answered:

“O Wood-Sun thou wottest our battle and the way wherein we fare:

That oft at the battle’s beginning the helm and the hauberk we bear;

Lest the shaft of the fleeing coward or the bow at adventure bent

Should slay us ere the need be, ere our might be given and spent.

Yet oft ere the fight is over, and Doom hath scattered the foe,

No leader of the people by his war-gear shall ye know,

But by his hurts the rather, from the cot-carle and the thrall:

For when all is done that a man may, ’tis the hour for a man to fall.”

She yet smiled as she said in answer:

“O Folk-wolf, heed and hearken; for when shall thy life be spent

And the Folk wherein thou dwellest with thy death be well content?

Whenso folk need the fire, do they hew the apple-tree,

And burn the Mother of Blossom and the fruit that is to be?

Or me wilt thou bid to thy grave-mound because thy battle-wrath

May nothing more be bridled than the whirl wind on his path?

So hearken and do my bidding, for the hauberk shalt thou bear

E’en when the other warriors cast off their battle-gear.

So come thou, come unwounded from the war-field of the south,

And sit with me in the beech-wood, and kiss me, eyes and mouth.”

And she kissed him in very deed, and made much of him, and fawned on him, and laid her hand on his breast, and he was soft and blithe with her, but at last he laughed and said:

“God’s Daughter, long hast thou lived, and many a matter seen,

And men full often grieving for the deed that might have been;

But here my heart thou wheedlest as a maid of tender years

When first in the arms of her darling the horn of war she hears.

Thou knowest the axe to be heavy, and the sword, how keen it is;

But that Doom of which thou hast spoken, wilt thou not tell of this,

God’s Daughter, how it sheareth, and how it breaketh through

Each wall that the warrior buildeth, yea all deeds that he may do?

What might in the hammer’s leavings, in the fire’s thrall shall abide

To turn that Folks’ o’erwhelmer from the fated warrior’s side?”

Then she laughed in her turn, and loudly; but so sweetly that the sound of her voice mingled with the first song of a newly awakened wood-thrush sitting on a rowan twig on the edge of the Wood-lawn. But she said:

“Yea, I that am God’s Daughter may tell thee never a whit

From what land cometh the hauberk nor what smith smithied it,

That thou shalt wear in the handplay from the first stroke to the last;

But this thereof I tell thee, that it holdeth firm and fast

The life of the body it lappeth, if the gift of the Godfolk it be.

Lo this is the yoke-mate of doom, and the gift of me unto thee.”

Then she leaned down from the stone whereon they sat, and her hand was in the dewy grass for a little, and then it lifted up a dark grey rippling coat of rings; and she straightened herself in the seat again, and laid that hauberk on the knees of Thiodolf, and he put his hand to it, and turned it about, while he pondered long: then at last he said:

“What evil thing abideth with this warder of the strife,

This burg and treasure chamber for the hoarding of my life?

For this is the work of the dwarfs, and no kindly kin of the earth;

And all we fear the dwarf-kin and their anger and sorrow and mirth.”

She cast her arms about him and fondled him, and her voice grew sweeter than the voice of any mortal thing as she answered:

“No ill for thee, beloved, or for me in the hauberk lies;

No sundering grief is in it, no lonely miseries.

But we shall abide together, and that new life I gave,

For a long while yet henceforward we twain its joy shall have.

Yea, if thou dost my bidding to wear my gift in the fight

No hunter of the wild-wood at the changing of the night

Shall see my shape on thy grave-mound or my tears in the morning find

With the dew of the morning mingled; nor with the evening wind

Shall my body pass the shepherd as he wandereth in the mead

And fill him with forebodings on the eve of the Wolfings’ need.

Nor the horse-herd wake in the midnight and hear my fateful cry;

Nor yet shall the Wolfing women hear words on the wind go by

As they weave and spin the night down when the House is gone to the war,

And weep for the swains they wedded and the children that they bore.

Yea do my bidding, O Folk-wolf, lest a grief of the Gods should weigh

On the ancient House of the Wolfings and my death o’ercloud its day.”

And still she clung about him, while he spake no word of yea or nay: but at the last he let himself glide wholly into her arms, and the dwarf-wrought hauberk fell from his knees and lay on the grass.

So they abode together in that wood-lawn till the twilight was long gone, and the sun arisen for some while. And when Thiodolf stepped out of the beech-wood into the broad sunshine dappled with the shadow of the leaves of the hazels moving gently in the fresh morning air, he was covered from the neck to the knee by a hauberk of rings dark and grey and gleaming, fashioned by the dwarfs of ancient days.

CHAPTER IV—THE HOUSE FARETH TO THE WAR

Now when Thiodolf came back to the habitations of the kindred the whole House was astir, both thrall-men and women, and free women hurrying from cot to stithy, and from stithy to hall bearing the last of the war-gear or raiment for the fighting-men. But they for their part were some standing about anigh the Man’s-door, some sitting gravely within the hall, some watching the hurry of the thralls and women from the midmost of the open space amidst of the habitations, whereon there stood yet certain wains which were belated: for the most of the wains were now standing with the oxen already yoked to them down in the meadow past the acres, encircled by a confused throng of kine and horses and thrall-folk, for thither had all the beasts for the slaughter, and the horses for the warriors been brought; and there were the horses tethered or held by the thralls; some indeed were already saddled and bridled, and on others were the thralls doing the harness.

But as for the wains of the Markmen, they were stoutly framed of ash-tree with panels of aspen, and they were broad-wheeled so that they might go over rough and smooth. They had high tilts over them well framed of willow-poles covered over with squares of black felt over-lapping like shingles; which felt they made of the rough of their fleeces, for they had many sheep. And these wains were to them for houses upon the way if need were, and therein as now were stored their meal and their war-store and after fight they would flit their wounded men in them, such as were too sorely hurt to back a horse: nor must it be hidden that whiles they looked to bring back with them the treasure of the south. Moreover the folk if they were worsted in any battle, instead of fleeing without more done, would often draw back fighting into a garth made by these wains, and guarded by some of their thralls; and there would abide the onset of those who had thrust them back in the field. And this garth they called the Wain-burg.

So now stood three of these wains aforesaid belated amidst of the habitations of the House, their yoke-beasts standing or lying down unharnessed as yet to them: but in the very midst of that place was a wain unlike to them; smaller than they but higher; square of shape as to the floor of it; built lighter than they, yet far stronger; as the warrior is stronger than the big carle and trencher-licker that loiters about the hall; and from the midst of this wain arose a mast made of a tall straight fir-tree, and thereon hung the banner of the Wolfings, wherein was wrought the image of the Wolf, but red of hue as a token of war, and with his mouth open and gaping upon the foemen. Also whereas the other wains were drawn by mere oxen, and those of divers colours, as chance would have it, the wain of the banner was drawn by ten black bulls of the mightiest of the herd, deep-dewlapped, high-crested and curly-browed; and their harness was decked with gold, and so was the wain itself, and the woodwork of it painted red with vermilion. There then stood the Banner of the House of the Wolfings awaiting the departure of the warriors to the hosting.

So Thiodolf stood on the top of the bent beside that same mound wherefrom he had blown the War-horn yester-eve, and which was called the Hill of Speech, and he shaded his eyes with his hand and looked around him; and even therewith the carles fell to yoking the beasts to the belated wains, and the warriors gathered together from out of the mixed throngs, and came from the Roof and the Man’s-door and all set their faces toward the Hill of Speech.

So Thiodolf knew that all was ready for departure, and it wanted but an hour of high-noon; so he turned about and went into the Hall, and there found his shield and his spear hanging in his sleeping place beside the hauberk he was wont to wear; then he looked, as one striving with thought, at his empty hauberk and his own body covered with the dwarf-wrought rings; nor did his face change as he took his shield and his spear and turned away. Then he went to the dais and there sat his foster-daughter (as men deemed her) sitting amidst of it as yester-eve, and now arrayed in a garment of fine white wool, on the breast whereof were wrought in gold two beasts ramping up against a fire-altar whereon a flame flickered; and on the skirts and the hems were other devices, of wolves chasing deer, and men shooting with the bow; and that garment was an ancient treasure; but she had a broad girdle of gold and gems about her middle, and on her arms and neck she wore great gold rings wrought delicately. By then there were few save the Hall-Sun under the Roof, and they but the oldest of the women, or a few very old men, and some who were ailing and might not go abroad. But before her on the thwart table lay the Great War-horn awaiting the coming of Thiodolf to give signal of departure.

Then went Thiodolf to the Hall-Sun and kissed and embraced her fondly, and she gave the horn into his hands, and he went forth and up on to the Hill of Speech, and blew thence a short blast on the horn, and then came all the Warriors flocking to the Hill of Speech, each man stark in his harness, alert and joyous.

Then presently through the Man’s-door came the Hall-Sun in that ancient garment, which fell straight and stiff down to her ancles as she stepped lightly and slowly along, her head crowned with a garland of eglantine. In her right hand also she held a great torch of wax lighted, whose flame amidst the bright sunlight looked like a wavering leaf of vermilion.

The warriors saw her, and made a lane for her, and she made her way through it up to the Hill of Speech, and she went up to the top of it and stood there holding the lighted candle in her hand, so that all might see it. Then suddenly was there as great a silence as there may be on a forenoon of summer; for even the thralls down in the meadow had noted what was toward, and ceased their talking and shouting, for as far off as they were, since they could see that the Hall-Sun stood on the Hill of Speech, for the wood was dark behind her; so they knew the Farewell Flame was lighted, and that the maiden would speak; and to all men her speech was a boding of good or of ill.

So she began in a sweet voice yet clear and far-reaching:

“O Warriors of the Wolfings by the token of the flame

That here in my right hand flickers, come aback to the House of the Name!

For there yet burneth the Hall-Sun beneath the Wolfing roof,

And this flame is litten from it, nor as now shall it fare aloof

Till again it seeth the mighty and the men to be gleaned from the fight.

So wend ye as weird willeth and let your hearts be light;

For through your days of battle all the deeds of our days shall be fair.

To-morrow beginneth the haysel, as if every carle were here;

And who knoweth ere your returning but the hook shall smite the corn?

But the kine shall go down to the meadow as their wont is every morn,

And each eve shall come back to the byre; and the mares and foals afield

Shall ever be heeded duly; and all things shall their increase yield.

And if it shall befal us that hither cometh a foe

Here have we swains of the shepherds good players with the bow,

And old men battle-crafty whose might is nowise spent,

And women fell and fearless well wont to tread the bent

Amid the sheep and the oxen; and their hands are hard with the spear

And their arms are strong and stalwart the battle shield to bear;

And store of weapons have we and the mighty walls of the stead;

And the Roof shall abide you steadfast with the Hall-Sun overhead.

Lo here I quench this candle that is lit from the Hall-Sun’s flame

Which unto the Wild-wood clearing with the kin of the Wolfings came

And shall wend with their departure to the limits of the earth;

Nor again shall the torch be lighted till in sorrow or in mirth,

Overthrown or overthrowing, ye come aback once more,

And bid me bear the candle before the Wolf of War.”

As she spake the word she turned the candle downward, and thrust it against the grass and quenched it indeed; but the whole throng of warriors turned about, for the bulls of the banner-wain lowered their heads in the yokes and began to draw, lowing mightily; and the wain creaked and moved on, and all the men-at-arms followed after, and down they went through the lanes of the corn, and a many women and children and old men went down into the mead with them.

In their hearts they all wondered what the Hall-Sun’s words might signify; for she had told them nought about the battles to be, saving that some should come back to the Mid-mark; whereas aforetime somewhat would she foretell to them concerning the fortune of the fight, and now had she said to them nothing but what their own hearts told them. Nevertheless they bore their crests high as they followed the Wolf down into the meadow, where all was now ready for departure. There they arrayed themselves and went down to the lip of Mirkwood-water; and such was their array that the banner went first, save that a band of fully armed men went before it; and behind it and about were the others as well arrayed as they. Then went the wains that bore their munition, with armed carles of the thrall-folk about them, who were ever the guard of the wains, and should never leave them night or day; and lastly went the great band of the warriors and the rest of the thralls with them.

As to their war-gear, all the freemen had helms of some kind, but not all of iron or steel; for some bore helms fashioned of horse-hide and bull-hide covered over with the similitude of a Wolf’s muzzle; nor were these ill-defence against a sword-stroke. Shields they all had, and all these had the image of the Wolf marked on them, but for many their thralls bore them on the journey. As to their body-armour some carried long byrnies of ring-mail, some coats of leather covered with splinters of horn laid like the shingles of a roof, and some skin-coats only: whereof indeed there were some of which tales went that they were better than the smith’s hammer-work, because they had had spells sung over them to keep out steel or iron.

But for their weapons, they bore spears with shafts not very long, some eight feet of our measure; and axes heavy and long-shafted; and bills with great and broad heads; and some few, but not many of the kindred were bowmen, and every freeman was girt with a sword; but of the swords some were long and two-edged, some short and heavy, cutting on one edge, and these were of the kind which they and our forefathers long after called ‘sax.’ Thus were the freemen arrayed.

But for the thralls, there were many bows among them, especially among those who were of blood alien from the Goths; the others bore short spears, and feathered broad arrows, and clubs bound with iron, and knives and axes, but not every man of them had a sword. Few iron helms they had and no ringed byrnies, but most had a buckler at their backs with no sign or symbol on it.

Thus then set forth the fighting men of the House of the Wolf toward the Thing-stead of the Upper-mark where the hosting was to be, and by then they were moving up along the side of Mirkwood-water it was somewhat past high-noon.

But the stay-at-home people who had come down with them to the meadow lingered long in that place; and much foreboding there was among them of evil to come; and of the old folk, some remembered tales of the past days of the Markmen, and how they had come from the ends of the earth, and the mountains where none dwell now but the Gods of their kindreds; and many of these tales told of their woes and their wars as they went from river to river and from wild-wood to wild-wood before they had established their Houses in the Mark, and fallen to dwelling there season by season and year by year whether the days were good or ill. And it fell into their hearts that now at last mayhappen was their abiding wearing out to an end, and that the day should soon be when they should have to bear the Hall-Sun through the wild-wood, and seek a new dwelling-place afar from the troubling of these newly arisen Welsh foemen.

And so those of them who could not rid themselves of this foreboding were somewhat heavier of heart than their wont was when the House went to the War. For long had they abided there in the Mark, and the life was sweet to them which they knew, and the life which they knew not was bitter to them: and Mirkwood-water was become as a God to them no less than to their fathers of old time; nor lesser was the mead where fed the horses that they loved and the kine that they had reared, and the sheep that they guarded from the Wolf of the Wild-wood: and they worshipped the kind acres which they themselves and their fathers had made fruitful, wedding them to the seasons of seed-time and harvest, that the birth that came from them might become a part of the kindred of the Wolf, and the joy and might of past springs and summers might run in the blood of the Wolfing children. And a dear God indeed to them was the Roof of the Kindred, that their fathers had built and that they yet warded against the fire and the lightening and the wind and the snow, and the passing of the days that devour and the years that heap the dust over the work of men. They thought of how it had stood, and seen so many generations of men come and go; how often it had welcomed the new-born babe, and given farewell to the old man: how many secrets of the past it knew; how many tales which men of the present had forgotten, but which yet mayhap men of times to come should learn of it; for to them yet living it had spoken time and again, and had told them what their fathers had not told them, and it held the memories of the generations and the very life of the Wolfings and their hopes for the days to be.