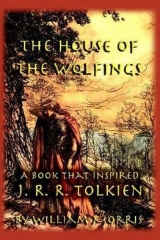

Текст книги "The House of the Wolfings"

Автор книги: William Morris

Жанры:

Историческое фэнтези

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Arinbiorn answered not, but his face waxed red, as if he were struggling with a weight hard to lift: then said Otter:

“But when will Thiodolf and the main battle be with us?”

Arinbiorn answered calmly: “Maybe in a little hour from now, or somewhat more.”

Said Otter: “My rede is that we abide him here, and when we are all met and well ordered together, fall on the Romans at once: for then shall we be more than they; whereas now we are far fewer, and moreover we shall have to set on them in their ground of vantage.”

Arinbiorn answered nothing; but an old man of the Bearings, one Thorbiorn, came up and spake:

“Warriors, here are we talking and taking counsel, though this is no Hallowed Thing to bid us what we shall do, and what we shall forbear; and to talk thus is less like warriors than old women wrangling over the why and wherefore of a broken crock. Let the War-duke rule here, as is but meet and right. Yet if I might speak and not break the peace of the Goths, then would I say this, that it might be better for us to fall on these Romans at once before they have cast up a dike about them, as Fox telleth is their wont, and that even in an hour they may do much.”

As he spake there was a murmur of assent about him, but Otter spake sharply, for he was grieved.

“Thorbiorn, thou art old, and shouldest not be void of prudence. Now it had been better for thee to have been in the wood to-day to order the women and the swains according to thine ancient wisdom than to egg on my young warriors to fare unwarily. Here will I abide Thiodolf.”

Then Thorbiorn reddened and was wroth; but Arinbiorn spake:

“What is this to-do? Let the War-duke rule as is but right: but I am now become a man of Thiodolf’s company; and he bade me haste on before to help all I might. Do thou as thou wilt, Otter: for Thiodolf shall be here in an hour’s space, and if much diking shall be done in an hour, yet little slaying, forsooth, shall be done, and that especially if the foe is all armed and slayeth women and children. Yea if the Bearing women be all slain, yet shall not Tyr make us new ones out of the stones of the waste to wed with the Galtings and the fish-eating Houses?—this is easy to be done forsooth. Yea, easier than fighting the Romans and overcoming them!”

And he was very wrath, and turned away; and again there was a murmur and a hum about him. But while these had been speaking aloud, Sweinbiorn had been talking softly to some of the younger men, and now he shook his naked sword in the air and spake aloud and sang:

“Ye tarry, Bears of Battle! ye linger, Sons of the Worm!

Ye crouch adown, O kindreds, from the gathering of the storm!

Ye say, it shall soon pass over and we shall fare afield

And reap the wheat with the war-sword and winnow in the shield.

But where shall be the corner wherein ye then shall abide,

And where shall be the woodland where the whelps of the bears shall hide

When ’twixt the snowy mountains and the edges of the sea

These men have swept the wild-wood and the fields where men may be

Of every living sword-blade, and every quivering spear,

And in the southland cities the yoke of slaves ye bear?

Lo ye! whoever follows I fare to sow the seed

Of the days to be hereafter and the deed that comes of deed.”

Therewith he waved his sword over his head, and made as if he would spur onward. But Arinbiorn thrust through the press and outwent him and cried out:

“None goeth before Arinbiorn the Old when the battle is pitched in the meadows of the kindred. Come, ye sons of the Bear, ye children of the Worm! And come ye, whosoever hath a will to see stout men die!”

Then on he rode nor looked behind him, and the riders of the Bearings and the Wormings drew themselves out of the throng, and followed him, and rode clattering over the meadow towards Wolfstead. A few of the others rode with them, and yet but a few. For they remembered the holy Folk-mote and the oath of the War-duke, and how they had chosen Otter to be their leader. Howbeit, man looked askance at man, as if in shame to be left behind.

But Otter bethought him in the flash of a moment, “If these men ride alone, they shall die and do nothing; and if we ride with them it may be that we shall overthrow the Romans, and if we be vanquished, it shall go hard but we shall slay many of them, so that it shall be the easier for Thiodolf to deal with them.”

Then he spake hastily, and bade certain men abide at the ford for a guard; then he drew his sword and rode to the front of his folk, and cried out aloud to them:

“Now at last has come the time to die, and let them of the Markmen who live hereafter lay us in howe. Set on, Sons of Tyr, and give not your lives away, but let them be dearly earned of our foemen.”

Then all shouted loudly and gladly; nor were they otherwise than exceeding glad; for now had they forgotten all other joys of life save the joy of fighting for the kindred and the days to be.

So Otter led them forth, and when he heard the whole company clattering and thundering on the earth behind him and felt their might enter into him, his brow cleared, and the anxious lines in the face of the old man smoothed themselves out, and as he rode along the soul so stirred within him that he sang out aloud:

“Time was when hot was the summer and I was young on the earth,

And I grudged me every moment that lacked its share of mirth.

I woke in the morn and was merry and all the world methought

For me and my heart’s deliverance that hour was newly wrought.

I have passed through the halls of manhood, I have reached the doors of eld,

And I have been glad and sorry, but ever have upheld

My heart against all trouble that none might call me sad,

But ne’er came such remembrance of how my heart was glad

In the afternoon of summer ’neath the still unwearied sun

Of the days when I was little and all deeds were hopes to be won,

As now at last it cometh when e’en in such-like tide,

For the freeing of my trouble o’er the fathers’ field I ride.”

Many men perceived that he sang, and saw that he was merry, howbeit few heard his very words, and yet all were glad of him.

Fast they rode, being wishful to catch up with the Bearings and the Wormings, and soon they came anigh them, and they, hearing the thunder of the horse-hoofs, looked and saw that it was the company of Otter, and so slacked their speed till they were all joined together with joyous shouting and laughter. So then they ordered the ranks anew and so set forward in great joy without haste or turmoil toward Wolfstead and the Romans. For now the bitterness of their fury and the sourness of their abiding wrath were turned into the mere joy of battle; even as the clear red and sweet wine comes of the ugly ferment and rough trouble of the must.

CHAPTER XXIII—THIODOLF MEETETH THE ROMANS IN THE WOLFING MEADOW

It was scarce an hour after this that the footmen of Thiodolf came out of the thicket road on to the meadow of the Bearings; there saw they men gathered on a rising ground, and they came up to them and saw how some of them were looking with troubled faces towards the ford and what lay beyond it, and some toward the wood and the coming of Thiodolf. But these were they whom Otter had bidden abide Thiodolf there, and he had sent two messengers to them for Thiodolf’s behoof that he might have due tidings so soon as he came out of the thicket: the first told how Otter had been compelled in a manner to fall on the Romans along with the riders of the Bearings and the Wormings, and the second who had but just then come, told how the Markmen had been worsted by the Romans, and had given back from the Wolfing dwellings, and were making a stand against the foemen in the meadow betwixt the ford and Wolfstead.

Now when Thiodolf heard of these tidings he stayed not to ask long questions, but led the whole host straightway down to the ford, lest the remnant of Otter’s men should be driven down there, and the Romans should hold the western bank against him.

At the ford there was none to withstand them, nor indeed any man at all; for the men whom Otter had set there, when they heard that the battle had gone against their kindred, had ridden their ways to join them. So Thiodolf crossed over the ford, he and his in good order all afoot, he like to the others; but for him he was clad in the Dwarf-wrought Hauberk, but was unhelmeted and bare no shield. Throng-plough was naked in his hand as he came up all dripping on to the bank and stood in the meadow of the Wolfings; his face was stern and set as he gazed straight onward to the place of the fray, but he did not look as joyous as his wont was in going down to the battle.

Now they had gone but a short way from the ford before the noise of the fight and the blowing of horns came down the wind to them, but it was a little way further before they saw the fray with their eyes; because the ground fell away from the river somewhat at first, and then rose and fell again before it went up in one slope toward the Wolfing dwellings.

But when they were come to the top of the next swelling of the ground, they beheld from thence what they had to deal with; for there round about a ground of vantage was the field black with the Roman host, and in the midst of it was a tangle of struggling men and tossing spears, and glittering swords.

So when they beheld the battle of their kindred they gave a great shout and hastened onward the faster; and they were ordered into the wedge-array and Thiodolf led them, as meet it was. And now even as they who were on the outward edge of the array and could see what was toward were looking on the battle with eager eyes, there came an answering shout down the wind, which they knew for the voice of the Goths amid the foemen, and then they saw how the ring of the Romans shook and parted, and their array fell back, and lo the company of the Markmen standing stoutly together, though sorely minished; and sure it was that they had not fled or been scattered, but were ready to fall one over another in one band, for there were no men straggling towards the ford, though many masterless horses ran here and there about the meadow. Now, therefore, none doubted but that they would deliver their friends from the Romans, and overthrow the foemen.

But now befel a wonder, a strange thing to tell of. The Romans soon perceived what was adoing, whereupon the half of them turned about to face the new comers, while the other half still withstood the company of Otter: the wedge-array of Thiodolf drew nearer and nearer till it was hard on the place where it should spread itself out to storm down on the foe, and the Goths beset by the Romans made them ready to fall on from their side. There was Thiodolf leading his host, and all men looking for the token and sign to fall on; but even as he lifted up Throng-plough to give that sign, a cloud came over his eyes and he saw nought of all that was before him, and he staggered back as one who hath gotten a deadly stroke, and so fell swooning to the earth, though none had smitten him. Then stayed was the wedge-array even at the very point of onset, and the hearts of the Goths sank, for they deemed that their leader was slain, and those who were nearest to him raised him up and bore him hastily aback out of the battle; and the Romans also had beheld him fall, and they also deemed him dead or sore hurt, and shouted for joy and loitered not, but stormed forth on the wedge-array like valiant men; for it must be told that they, who erst out-numbered the company of Otter, were now much out-numbered, but they deemed it might well be that they could dismay the Goths since they had been stayed by the fall of their leader; and Otter’s company were wearied with sore fighting against a great host. Nevertheless these last, who had not seen the fall of Thiodolf (for the Romans were thick between him and them) fell on with such exceeding fury that they drove the Romans who faced them back on those who had set on the wedge-array, which also stood fast undismayed; for he who stood next to Thiodolf, a man big of body, and stout of heart, hight Thorolf, hove up a great axe and cried out aloud:

“Here is the next man to Thiodolf! here is one who will not fall till some one thrusts him over, here is Thorolf of the Wolfings! Stand fast and shield you, and smite, though Thiodolf be gone untimely to the Gods!”

So none gave back a foot, and fierce was the fight about the wedge-array; and the men of Otter—but there was no Otter there, and many another man was gone, and Arinbiorn the Old led them—these stormed on so fiercely that they cleft their way through all and joined themselves to their kindred, and the battle was renewed in the Wolfing meadow. But the Romans had this gain, that Thiodolf’s men had let go their occasion for falling on the Romans with their line spread out so that every man might use his weapons; yet were the Goths strong both in valiancy and in numbers, nor might the Romans break into their array, and as aforesaid the Romans were the fewer, for it was less than half of their host that had pursued the Goths when they had been thrust back from their fierce onset: nor did more than the half seem needed, so many of them had fallen along with Otter the War-duke and Sweinbiorn of the Bearings, that they seemed to the Romans but a feeble band easy to overcome.

So fought they in the Wolfing meadow in the fifth hour after high-noon, and neither yielded to the other: but while these things were a-doing, men laid Thiodolf adown aloof from the battle under a doddered oak half a furlong from where the fight was a-doing, round whose bole clung flocks of wool from the sheep that drew around it in the hot summer-tide and rubbed themselves against it, and the ground was trodden bare of grass round the bole, and close to the trunk was worn into a kind of trench. There then they laid Thiodolf, and they wondered that no blood came from him, and that there was no sign of a shot-weapon in his body.

But as for him, when he fell, all memory of the battle and what had gone before it faded from his mind, and he passed into sweet and pleasant dreams wherein he was a lad again in the days before he had fought with the three Hun-Kings in the hazelled field. And in these dreams he was doing after the manner of young lads, sporting in the meadows, backing unbroken colts, swimming in the river, going a-hunting with the elder carles. And especially he deemed that he was in the company of one old man who had taught him both wood-craft and the handling of weapons: and fair at first was his dream of his doings with this man; he was with him in the forge smithying a sword-blade, and hammering into its steel the thin golden wires; and fishing with an angle along with him by the eddies of Mirkwood-water; and sitting with him in an ingle of the Hall, the old man telling a tale of an ancient warrior of the Wolfings hight Thiodolf also: then suddenly and without going there, they were in a little clearing of the woods resting after hunting, a roe-deer with an arrow in her lying at their feet, and the old man was talking, and telling Thiodolf in what wise it was best to go about to get the wind of a hart; but all the while there was going on the thunder of a great gale of wind through the woodland boughs, even as the drone of a bag-pipe cleaves to the tune. Presently Thiodolf arose and would go about his hunting again, and stooped to take up his spear, and even therewith the old man’s speech stayed, and Thiodolf looked up, and lo, his face was white like stone, and he touched him, and he was hard as flint, and like the image of an ancient god as to his face and hands, though the wind stirred his hair and his raiment, as they did before. Therewith a great pang smote Thiodolf in his dream, and he felt as if he also were stiffening into stone, and he strove and struggled, and lo, the wild-wood was gone, and a white light empty of all vision was before him, and as he moved his head this became the Wolfing meadow, as he had known it so long, and thereat a soft pleasure and joy took hold of him, till again he looked, and saw there no longer the kine and sheep, and the herd-women tending them, but the rush and turmoil of that fierce battle, the confused thundering noise of which was going up to the heavens; for indeed he was now fully awake again.

So he stood up and looked about; and around him was a ring of the sorrowful faces of the warriors, who had deemed that he was hurt deadly, though no hurt could they find upon him. But the Dwarf-wrought Hauberk lay upon the ground beside him; for they had taken it off him to look for his hurts.

So he looked into their faces and said: “What aileth you, ye men? I am alive and unhurt; what hath betided?”

And one said: “Art thou verily alive, or a man come back from the dead? We saw thee fall as thou wentest leading us against the foe as if thou hadst been smitten by a thunder-bolt, and we deemed thee dead or grievously hurt. Now the carles are fighting stoutly, and all is well since thou livest yet.”

So he said: “Give me the point and edges that I know, that I may smite myself therewith and not the foemen; for I have feared and blenched from the battle.”

Said an old warrior: “If that be so, Thiodolf, wilt thou blench twice? Is not once enough? Now let us go back to the hard handplay, and if thou wilt, smite thyself after the battle, when we have once more had a man’s help of thee.”

Therewith he held out Throng-plough to him by the point, and Thiodolf took hold of the hilts and handled it and said: “Let us hasten, while the Gods will have it so, and while they are still suffering me to strike a stroke for the kindred.”

And therewith he brandished Throng-plough, and went forth toward the battle, and the heart grew hot within him, and the joy of waking life came back to him, the joy which but erewhile he had given to a mere dream.

But the old man who had rebuked him stooped down and lifted the Hauberk from the ground, and cried out after him, “O Thiodolf, and wilt thou go naked into so strong a fight? and thou with this so goodly sword-rampart?”

Thiodolf stayed a moment, and even therewith they looked, and lo! the Romans giving back before the Goths and the Goths following up the chase, but slowly and steadily. Then Thiodolf heeded nothing save the battle, but ran forward hastily, and those warriors followed him, the old man last of all holding the Hauberk in his hand, and muttering:

“So fares hot blood to the glooming and the world beneath the grass;

And the fruit of the Wolfings’ orchard in a flash from the world must pass.

Men say that the tree shall blossom in the garden of the folk,

And the new twig thrust him forward from the place where the old one broke,

And all be well as aforetime: but old and old I grow,

And I doubt me if such another the folk to come shall know.”

And he still hurried forward as fast as his old body might go, so that he might wrap the safeguard of the Hauberk round Thiodolf’s body.

CHAPTER XXIV—THE GOTHS ARE OVERTHROWN BY THE ROMANS

Now rose up a mighty shout when Thiodolf came back to the battle of the kindreds, for many thought he had been slain; and they gathered round about him, and cried out to him joyously out of their hearts of good-fellowship, and the old man who had rebuked Thiodolf, and who was Jorund of the Wolfings, came up to him and reached out to him the Hauberk, and he did it on scarce heeding; for all his heart and soul was turned toward the battle of the Romans and what they were a-doing; and he saw that they were falling back in good order, as men out-numbered, but undismayed. So he gathered all his men together and ordered them afresh; for they were somewhat disarrayed with the fray and the chase: and now he no longer ordered them in the wedge array, but in a line here three deep, here five deep, or more, for the foes were hard at hand, and outnumbered, and so far overcome, that he and all men deemed it a little matter to give these their last overthrow, and then onward to Wolf-stead to storm on what was left there and purge the house of the foemen. Howbeit Thiodolf bethought him that succour might come to the Romans from their main-battle, as they needed not many men there, since there was nought to fear behind them: but the thought was dim within him, for once more since he had gotten the Hauberk on him the earth was wavering and dream-like: he looked about him, and nowise was he as in past days of battle when he saw nought but the foe before him, and hoped for nothing save the victory. But now indeed the Wood-Sun seemed to him to be beside him, and not against his will, as one besetting and hindering him, but as though his own longing had drawn her thither and would not let her depart; and whiles it seemed to him that her beauty was clearer to be seen than the bodies of the warriors round about him. For the rest he seemed to be in a dream indeed, and, as men do in dreams, to be for ever striving to be doing something of more moment than anything which he did, but which he must ever leave undone. And as the dream gathered and thickened about him the foe before him changed to his eyes, and seemed no longer the stern brown-skinned smooth-faced men under their crested iron helms with their iron-covered shields before them, but rather, big-headed men, small of stature, long-bearded, swart, crooked of body, exceeding foul of aspect. And he looked on and did nothing for a while, and his head whirled as though he had been grievously smitten.

Thus tarried the kindreds awhile, and they were bewildered and their hearts fell because Thiodolf did not fly on the foemen like a falcon on the quarry, as his wont was. But as for the Romans, they had now stayed, and were facing their foes again, and that on a vantage-ground, since the field sloped up toward the Wolfing dwelling; and they gathered heart when they saw that the Goths tarried and forbore them. But the sun was sinking, and the evening was hard at hand.

So at last Thiodolf led forward with Throng-plough held aloft in his right hand; but his left hand he held out by his side, as though he were leading someone along. And as he went, he muttered: “When will these accursed sons of the nether earth leave the way clear to us, that we may be alone and take pleasure each in each amidst of the flowers and the sun?”

Now as the two hosts drew near to one another, again came the sound of trumpets afar off, and men knew that this would be succour coming to the Romans from their main-battle, and the Romans thereon shouted for joy, and the host of the kindreds might no longer forbear, but rushed on fiercely against them; and for Thiodolf it was now come to this, that so entangled was he in his dream that he rather went with his men than led them. Yet had he Throng-plough in his right hand, and he muttered in his beard as he went, “Smite before! smite behind! and smite on the right hand! but never on the left!”

Thus then they met, and as before, neither might the Goths sweep the Romans away, nor the Romans break the Goths into flight; yet were many of the kindred anxious and troubled, since they knew that aid was coming to the Romans, and they heard the trumpets sounding nearer and more joyous; and at last, as the men of the kindreds were growing a-wearied with fighting, they heard those horns as it were in their very ears, and the thunder of the tramp of footmen, and they knew that a fresh host of men was upon them; then those they had been fighting with opened before them, falling aside to the right and the left, and the fresh men passing between them, fell on the Goths like the waters of a river when a sluice-gate is opened. They came on in very good order, never breaking their ranks, but swift withal, smiting and pushing before them, and so brake through the array of the Goth-folk, and drave them this way and that way down the slopes.

Yet still fought the warriors of the kindred most valiantly, making stand and facing the foe again and again in knots of a score or two score, or maybe ten score; and though many a man was slain, yet scarce any one before he had slain or hurt a Roman; and some there were, and they the oldest, who fought as if they and the few about them were all the host that was left to the folk, and heeded not that others were driven back, or that the Romans gathered about them, cutting them off from all succour and aid, but went on smiting till they were felled with many strokes.

Howbeit the array of the Goths was broken and many were slain, and perforce they must give back, and it seemed as if they would be driven into the river and all be lost.

But for Thiodolf, this befell him: that at first, when those fresh men fell on, he seemed, as it were, to wake unto himself again, and he cried aloud the cry of the Wolf, and thrust into the thickest of the fray, and slew many and was hurt of none, and for a moment of time there was an empty space round about him, such fear he cast even into the valiant hearts of the foemen. But those who had time to see him as they stood by him noted that he was as pale as a dead man, and his eyes set and staring; and so of a sudden, while he stood thus threatening the ring of doubtful foemen, the weakness took him again, Throng-plough tumbled from his hand, and he fell to earth as one dead.

Then of those who saw him some deemed that he had been striving against some secret hurt till he could do no more; and some that there was a curse abroad that had fallen upon him and upon all the kindreds of the Mark; some thought him dead and some swooning. But, dead or alive, the warriors would not leave their War-duke among the foemen, so they lifted him, and gathered about him a goodly band that held its own against all comers, and fought through the turmoil stoutly and steadily; and others gathered to them, till they began to be something like a host again, and the Romans might not break them into knots of desperate men any more.

Thus they fought their way, Arinbiorn of the Bearings leading them now, with a mind to make a stand for life or death on some vantage-ground; and so, often turning upon the Romans, they came in array ever growing more solid to the rising ground looking one way over the ford and the other to the slopes where the battle had just been. There they faced the foe as men who may be slain, but will be driven no further; and what bowmen they had got spread out from their flanks and shot on the Romans, who had with them no light-armed, or slingers or bowmen, for they had left them at Wolf-stead. So the Romans stood a while, and gave breathing-space to the Markmen, which indeed was the saving of them: for if they had fallen on hotly and held to it steadily, it is like that they would have passed over all the bodies of the Markmen: for these had lost their leader, either slain, as some thought, or, as others thought, banned from leadership by the Gods; and their host was heavy-hearted; and though it is like that they would have stood there till each had fallen over other, yet was their hope grown dim, and the whole folk brought to a perilous and fearful pass, for if these were slain or scattered there were no more but they, and nought between fire and the sword and the people of the Mark.

But once again the faint-heart folly of the Roman Captain saved his foes: for whereas he once thought that the whole power of the Markmen lay in Otter and his company, and deemed them too little to meddle with, so now he ran his head into the other hedge, and deemed that Thiodolf’s company was but a part of the succour that was at hand for the Goths, and that they were over-big for him to meddle with.

True it is also that now dark night was coming on, and the land was unknown to the Romans, who moreover trusted not wholly to the dastards of the Goths who were their guides and scouts: furthermore the wood was at hand, and they knew not what it held; and with all this and above it all, it is to be said that over them also had fallen a dread of some doom anear; for those habitations amidst of the wild-woods were terrible to them as they were dear to the Goths; and the Gods of their foemen seemed to be lying in wait to fall upon them, even if they should slay every man of the kindreds.

So now having driven back the Goths to that height over the ford, which indeed was no stronghold, no mountain, scarce a hill even, nought but a gentle swelling of the earth, they forebore them; and raising up the whoop of victory drew slowly aback, picking up their own dead and wounded, and slaying the wounded Markmen. They had with them also some few captives, but not many; for the fighting had been to the death between man and man on the Wolfing Meadow.

CHAPTER XXV—THE HOST OF THE MARKMEN COMETH INTO THE WILD-WOOD

Yet though the Romans were gone, the Goth-folk were very hard bested. They had been overthrown, not sorely maybe if they had been in an alien land, and free to come and go as they would; yet sorely as things were, because the foeman was sitting in their own House, and they must needs drag him out of it or perish: and to many the days seemed evil, and the Gods fighting against them, and both the Wolfings and the other kindreds bethought them of the Hall-Sun and her wisdom and longed to hear of tidings concerning her.

But now the word ran through the host that Thiodolf was certainly not slain. Slowly he had come to himself, and yet was not himself, for he sat among his men gloomy and silent, clean contrary to his wont; for hitherto he had been a merry man, and a joyous fellow.

Amidst of the ridge whereon the Markmen now abode, there was a ring made of the chief warriors and captains and wise men who had not been slain or grievously hurt in the fray, and amidst them all sat Thiodolf on the ground, his chin sunken on his breast, looking more like a captive than the leader of a host amidst of his men; and that the more as his scabbard was empty; for when Throng-plough had fallen from his hand, it had been trodden under foot, and lost in the turmoil. There he sat, and the others in that ring of men looked sadly upon him; such as Arinbiorn of the Bearings, and Wolfkettle and Thorolf of his own House, and Hiarandi of the Elkings, and Geirbald the Shielding, the messenger of the woods, and Fox who had seen the Roman Garth, and many others. It was night now, and men had lighted fires about the host, for they said that the Romans knew where to find them if they listed to seek; and about those fires were men eating and drinking what they might come at, but amidmost of that ring was the biggest fire, and men turned them towards it for counsel and help, for elsewhere none said, “What do we?” for they were heavy-hearted and redeless, since the Gods had taken the victory out of their hands just when they seemed at point to win it.