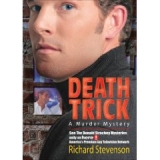

Текст книги "Death Trick "

Автор книги: Richard Stevenson

Жанры:

Слеш

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

DEATH TRICK

by

Richard Stevenson

For Chuck

for Fred, David, Bob, Ralph and George

for H.

and for Robert Berndt

1

The woman's voice was full of the music of business.

"Donald Strachey?"

"Yo."

"Mr. Stuart Blount is calling. One moment please."

I hung up.

Cars were double-parked on both sides of Central Avenue, and I watched an Albany police cruiser negotiate the course like a Conestoga wagon up the Donner Pass. By Thanksgiving it could be in Schenectady.

Again. "Donald Strachey?"

"Speaking."

"We were—disconnected, sir. Stuart Blount will be with you in just a moment."

I hung up.

The sky over Jimmy's Lounge was slate gray and a cold wind chewed at the crumbling caulking around the win-dowpane next to me. Five weeks after Labor Day and already winter was sliding across the state from Buffalo like a new Ice Age. I found some masking tape in the back of my desk drawer. I ripped off a long strip and pressed it against the grime where the pane met the frame.

Ring, ring.

"Strachey."

"Mr. Strachey, this is Stuart Blount. I've been trying to reach you."

"The damn line's been tied up. What can I do for you, Mr. Blount?"

"My attorney, Jay Tarbell, tells me you've handled missing-person type situations, and I seem to have been, ah, saddled with one. Perhaps you've seen it on the media."

I said yes, I had.

"I'd much appreciate your getting together with Mrs. Blount and me to discuss the situation. You probably understand that the matter could develop into an extended time frame. Are you available?"

I pitched the Gay Community News I'd been reading for the past hour onto the sooty stack of Advocates and GCNs below the windowsill. Down on Central an old blue Pinto was stalled sideways in the middle of the street, and the midday traffic was backing up on both sides. A foot patrolman glanced over his shoulder and ambled into Jimmy's.

I said, "I'll do what I can to clear out a block of time. How does next Thursday look?"

"In point of fact, Mr. Strachey, I was thinking hopefully we could do business sooner than that. I could work something out for this afternoon. As you know, we've got one hell of a problem situation over here."

It was that, though Blount spoke in the tones of a man who hadn't exactly been unhinged by it—if when all about you are losing theirs, grace under pressure, or whatever.

"I'll make some arrangements," I told him. "Where's your office?"

"Twin Towers, but why don't we make it at my residence? Mrs. Blount will, ah, wish to be present." He gave me the address. "Say, one-thirty?"

"I'll be there."

There were two banks within close walking distance of Twin Towers on Washington Avenue. I phoned my lover's ex-roommate's ex-lover, who worked at the Mechanics Exchange Bank. He called back five minutes later with the information that there was no danger of my depleting Stuart Blount's checking account anytime in the current century.

I walked down to Elmo's at Central and Lexington and ordered a diet Pepsi and a roast-beef sub with extra meat. I wrote Elmo a check for the $2.93 and made sure I had a State Bank deposit slip with me for after I'd paid my call at the Blounts'.

They lived in a three-story neo-Romanesque brownstone on State Street overlooking Washington Park. The place was in the middle of "the block," which I knew well enough, if only from the street. The buildings had a solid Edwardian propriety about them, the sort of neighborhood Lady Bellamy might have visited if the Titanic had made it across. Those houses that

hadn't been carved up into roomy high-ceilinged apartments for professional people and upper-echelon state bureaucrats were still occupied by families that were rich and, by and large, straight. In recent years my close contact with both groups had been relegated to mainly business.

The heavy oak door had a big oval of glass in it, beveled at the edges, with the name "Blount" engraved in the center in a fancy script. The Blount family was not new to State Street.

I rang the bell and stood shivering on the stoop, wishing I'd worn a sweater under my corduroy jacket. I looked at my reflection in the polished glass and checked my tie, a pricey tan suede job that had been a gift from Brigit's mother back when she still referred to me as "our Donald" and not "that sneaking fairy." "I'd once tossed the tie in a Goodwill box, then bought it back a month later for thirty-five cents; it was the only one I owned, and it helped clients like the Blounts meet their need to take me seriously.

A muscular brown woman in a black dress and white apron led me through the foyer, past a ticking grandfather clock into a pale yellow room with a crystal chandelier. Over a walnut sideboard with silver candlesticks were portraits of two early nineteenth century types, a man and a woman, who looked as though they'd absorbed their Cotton Mather. The oriental scatter rugs on the polished oak floor had held their color, and my fee went up as I crossed the room.

The brown woman recited: "Mr. and Mrs. Blount will be with you in just a moment," and left. Big Michael Korda fans, the Blounts. I seated myself on a winged mahogany-trimmed Empire sofa upholstered in deep-blue and off-white stripes of silk. Not a piece of furniture to take off your shoes and curl up on. I sat like a debutante with a teacup on her knee and looked out the bay window to my right and saw the exact tree in the park under which I had met Timmy Callahan. I smiled.

"Mr. Strachey—Hello! I'm Stuart Blount, and this is Mrs. Blount."

He strode toward me from the foyer, moving like a clipper ship, an elegant hand coming out of the sleeve of a gray, chalk-striped business suit. He had a full head of wavy gray hair and a nicely chiseled face with the lines of age in the most flattering

places, as if he'd picked up the design during a February golfing jaunt to the Algarve.

Mrs. Blount, a handsome, slim woman who could have been her husband's sister, wore a mauve dress of a style and cut that would not go out of fashion. Her movements had a calculatedly loose, finishing-school cockiness about them that came across as a kind of stiffness. She carried a small glass ashtray in her right hand and offered me her left. Her tanned and braceleted jingly-jangly arm raised up like a drawbridge, and she said "Hello" in a voice that once must have been musical.

I declined Mrs. Blount's offer of "refreshment"—the bank would be closing at three—and resumed my perch on the sofa.

The Blounts faced me from twin Chippendale chairs with lion's-claw feet across a glass-topped coffee table. My stained desert

boots with the frazzled stitching were visible through the glass.

"You come very well recommended," Stuart Blount said, nodding and trying to convince himself of something. "Jay Tarbell tells me you have quite a reputation around, ah, Albany, and Jane and I are grateful that you could rearrange your affairs and consider our son's rather problematical situation on such short notice."

I said, "Luckily a hole opened up in my schedule." I was ready to join them if they clutched their sides and shrieked with laughter.

"Well, we're very fortunate then," Blount said, feigning credulity like a man who knew what was important, "because you've certainly got your work cut out for you. The police have been searching for William for nearly a week now, Mr. Strachey, and they haven't so much as turned up a trace of the boy. However, it's my understanding that you'll have access to resources that the police are, ah, unfamiliar with, relatively speaking." He gave me a strained smile. "We're certainly hoping that you can help us out, Mr. Strachey. Can you?"

They leaned toward me just perceptibly. I said, "What is it you want me to do?"

"Why—find our son. Wasn't that clear? And bring him home to us."

Maybe there had been a misunderstanding. "Let me get this straight. Your son is William Blount—the William Blount

who was charged this week with second-degree murder. He's the 'missing person' we're talking about here? Or am I confused?"

Jane Blount shot her husband an impatient look and removed a Silva Thin from a gold box on the coffee table. Blount shifted in his chair and said, "Why, yes, William Blount is our son. I thought you understood that—from the media coverage. Do you think you can locate the boy?"

"I might. And then what?"

"Then what? I don't follow."

"I mean, do you want me to gather evidence that will clear your son of the charge? That's what I'm usually hired to do in these cases. I've done it."

"Oh, we'll handle the legal end of it," Blount said, waving the matter away. "You'll simply find William and bring him to Jane and me. You won't need to concern yourself with the, ah, judicial processes, Mr. Strachey. That's all being taken care of."

"How so?"

Jane Blount lit her cigarette, which dangled from one corner of her mouth, and from the other corner she spoke to me with a pained earnestness. "Jay Tarbell is helping us out—he's a dear man, do you know Jay? And hopefully this ugly business can be cleared up with a minimum of upset for all concerned. It's been such a ghastly experience for Stuart and me, and we're terribly anxious for it to be over with just as soon as possible. But Billy, naturally, must take the first step by coming home and facing up to his responsibilities."

She sounded like a mother whose son had knocked up the trashman's daughter and a settlement was in the offing. She dragged on the cigarette and blew a stream of smoke up toward a humming little vent in the ceiling, which inhaled the cloud.

I said, "I know Tarbell by reputation. If anyone in Albany can get your son out of this, he's the one. I take it you believe your son is innocent."

They looked irritated. Not injured, not offended, just irritated. "Well, we certainly hope so," Blount said. "My God, I'd hate to think William was even capable of such a thing. But let me emphasize, Mr. Strachey, that the question of William's guilt or innocence is a matter to be dealt with elsewhere. That

end of it would be outside your purview, as I see it. Disposition of the case would be a matter for the courts to concern themselves with, wouldn't you agree? By way of preparation for that eventuality, however, perhaps you could give us an estimate on how long it might take you to locate William."

Something was screwy here, but I didn't know what. "I'd had clients in similar situations, but none so chipper and optimistic as the Blounts. I studied them for a moment, with no result. I said, "No, I can't. Two days, a week, a month—it's hard to say. I'd have an idea in a couple of days of what I'd be up against. I'd need a good bit of help from you two."

"You'll have it," Blount said. "Will you take the case?"

"You understand that once I locate your son and he agrees to come home, you and Tarbell could meet with him and then he'd have to go straight to the police. That's the law. If he didn't, I'd have to report it. There'd be no funny stuff, right? Flying down to Rio or whatever."

I doubted this was what the Blounts had in mind, though it had happened to me once before. I'd rounded up a client's embezzler-husband, who, instead of turning himself in, flashed his three hundred thou to my client and the happy couple left together on the first flight for Brazil. I'd lost my fee and barely escaped an abetting-a-felony charge and sometimes regretted I hadn't followed on the next plane.

"Mr. Strachey," Blount said, "Jay Tarbell is an officer of the court. He has a reputation to uphold in this community, as do Jane and I. We're hardly about to jeopardize our good names by participating in a conspiracy to circumvent justice. As I say, we are confident that some formal resolution to the matter can be arrived at that will satisfy all the interested parties. I'm afraid you'll just have to accept my word on that." He gave me a sickly smile.

"I just thank God," Jane Blount put in, "that we live in modern times."

What were they up to? Stuart Blount had a reputation around town as a high-toned wheeler-dealer—suburban real estate, shopping malls, cozy connections with the politically well placed. And while I supposed there were jurisdictions in the State of New York where you could still get a murder fixed,

I doubted Albany County was one of them. In the thirties, I guessed, but not in 1979. Maybe the Blounts held a genuine abiding faith in their son's innocence and were confident that, with a nudge from them here and there up the line, justice would triumph. It was a topic they didn't seem to want to go into.

I said, "Have you already done a deal with the DA, or what? I like to know what I'm getting into. I've got a license to keep."

Jane Blount's eyes flashed and she sucked furiously on her cigarette. Her husband sighed deeply. They were taking some unaccustomed abuse from me, and I guessed I knew why.

"Mr. Strachey, it's all being worked out with the appropriate authorities, believe me it is. What we're counting on, you see, is that a, ah, prison sentence can be avoided—that some alternative approach to William's rehabilitation can be worked out—if you get my drift."

I didn't. "Are you talking about a tour in the Peace Corps, or what? Fill me in. What's new on the correctional front?"

"I can tell you this much, Mr. Strachey. Judge Feeney has already been consulted, and he has given his blessing to the program we have in mind, as has the district attorney. Does that reassure you?"

Killer Feeney. Maybe he was going to allow the Blounts to have their son hanged at home, from the family chandelier.

I said, "If your son is innocent, isn't all this dealing a little premature?"

Blount squeezed his eyes shut for a long moment. Then, deciding I was probably worth all of this, he opened them and gazed at me wearily. "Let me explain. I'm a realist, Mr. Strachey. In my business, I have to be. I know what the evidence against William is. It's all been laid out for me. No, I don't believe that my son killed a man. William is troubled, yes, but I can't accept for a minute the notion that William would take a human life. It's just that the situation is—rather an intractable one, wouldn't you say? Jay Tarbell has gone over the evidence with me, and he's given his opinion, which is not favorable. Jane and I have been over it and over it, and we're simply doing what we think we must do."

"Making the best of a sorry state of affairs," Jane Blount added.

I said, "My fee is a hundred fifty dollars a day plus expenses. If you agree to that, and to giving me your full cooperation, I'll take the case."

They relaxed. "Thank you," Blount said. "Thank you, Mr. Strachey, for placing your trust in us."

I didn't trust them any farther than I could toss their walnut sideboard. But there were aspects of the case that interested me—for one, both the accused and his alleged victim were gay—and there was the additional incentive of my needing at least $2.93 to cover the check I'd written after lunch at Elmo's. I decided to risk becoming involved with these people I neither liked nor understood and then figure them out as I went along. It wasn't going to be the first time.

I said, "Tell me about your son. When did you last see him?"

I'd done it again. They looked at me as if I'd just said, "Up above the world so high/Like a tea tray in the sky." Except this time my irrelevant gibberish had them squirming in their Chippendale seats.

"We haven't seen William since before the, ah, crime," Blount finally said. "I believe it was some weeks ago—back in the latter part of the summer, if I recall precisely."

"That's not very precise."

"Billy has a lot of growing up to do," Jane Blount said. She flushed under her terrific tan.

"What happened the last time you saw Billy? Tell me; maybe that will help me begin to understand your son." And his parents.

Blount sucked in the corner of his mouth and sat looking droll. His wife gave me a full frontal of her nostrils, sighed deeply, and spoke. "On the morning of August the eighteenth, Stuart and I drove down from our cottage in Saratoga. When we arrived, Billy was here in our house with—a man."

"Uh-huh. Then what?"

"If you've read between the lines of the newspaper accounts, Mr. Strachey, you must have deduced that our son

has—homosexual tendencies. Billy is easily influenced, and he had spent the night on that sofa you're sitting on, Mr. Strachey, with a—a gay individual."

Tact. She went on. "Of course we had words with Billy about his behavior, and he—he simply walked out on us. Billy refused even to turn over his keys to the house, and Stuart was forced into having the locks changed. We haven't seen or heard from Billy since that day, despite our repeated messages offering to help him—as we've tried to help our son find his way on so many occasions in the past. We love Billy, you see, and we are not going to give up on him."

Tendencies. I remembered seeing Billy Blount's by-line on articles and editorials in the local gay community news bulletin a couple of years earlier—though not, I thought, recently—and I doubted he shared this assessment of his sexual makeup. Also, I tried to remember whether I'd ever run into him myself—I glanced down at the sofa, but it didn't ring a bell.

I said, "Billy was living here?"

"He has his own apartment," Stuart Blount said. "Billy has been on his own for several years now, but of course he's always been welcome here. However, you have to draw the line somewhere, am I right? I'm convinced I did the right thing."

I supposed he had, though the family dynamics here were starting to betray a certain complexity.

Jane Blount stabbed out her cigarette in the little dish in her palm. She gazed down at the butt and warbled, "Jay Tarbell tells us you may have—could we call it a "special entree"—with Billy's circle of acquaintances, Mr. Strachey?" She looked up at me with a clammy expectancy.

"We could call it that."

Blount pulled himself forward in a herky-jerky way and spoke the words. "Jay has mentioned to us that you are a, ah, avowed homosexual, Mr. Strachey, and that you can be counted on to be familiar with the, ah, gay life-style and, ah, milieu here in Albany."

"Yes, I'm gay."

"We're broad-minded," Blount said. He assumed a facial expression that resembled the work of an early cubist. "How

you live your life, Mr. Strachey, is none of our business. How William lives his life is very much our business. He's our only child, you see. He has no sisters or brothers."

Or siblings. "How old is your son?" I asked. "Mid-twenties?"

"Twenty-seven."

"He sounds old enough to make his own decisions."

"Despite our disagreements with Billy," Jane Blount said serenely, "he's always considered Stuart's and my opinions important. There's always been a kind of bond."

Scanty as the evidence was so far, I figured she had something there.

"You said you had words with Billy the last time you saw him. What did he say when he left?"

"Well—in point of fact," Blount said, shifting again, "Jane and I did the actual speaking. I did get a little hot under the collar, I have to admit. Billy did not express his feelings verbally. He simply walked out the door. With his houseguest."

Who probably never even sent a thank-you note. "Is that what Billy ordinarily does when he's angry? Walks away?"

Blount took on a martyred look. "Ah, if only he would! William's silence in August was hardly characteristic of our son, Mr. Strachey. When William becomes angry, he generally makes a speech—gives us all his propaganda." Or does a desecration number on the Blounts' Phyfe sofa. "But of course we've never bought it, all the slogans and so forth. Don't get me wrong, Mr. Strachey," Blount said, giving me his Picasso face again, "we respect the activists' positions, and we do not support legal discrimination against sodomites. But for William, it isn't the thing, you see? Not the road to the fulfilling type of life that is available to our son."

If Billy Blount was not an extremely angry young man, then he had to be a turnip. "What happens when I locate Billy and he refuses to drop by and hash things over with you two? That sounds to me like a distinct possibility. Bond or no bond, he's not likely to expect a sympathetic hearing from his family. Especially given the circumstances of the crime he's accused of."

Jane Blount went for another cigarette. Her husband

removed a sealed business-size envelope from his inside breast pocket and handed it to me. The printed return address was for Blount and Hackett, Investment Counselors, Twin Towers, Washington Avenue, Albany. "Give Billy this," he said. "It should make a difference."

I slid the envelope into my own breast pocket and could feel it find the rip at the bottom and begin to edge down into the lining. I asked what was in the envelope.

"That is private," Jane Blount said. "Private and personal. If Billy wants to tell you about it, that's his business. I doubt that he will. You just give it to him. He'll come home." She gave me a look that said, Understood?

Maybe he'd come home or maybe he wouldn't, but I didn't doubt that whatever was in the envelope was going to make an impression on Billy Blount.

I asked them to fill me in on their son's whereabouts, activities, and acquaintances over the past ten years, and for half an hour they rambled around the surface of Billy's social, educational, and occupational landscape. They offered little to go on.

Billy Blount had been graduated from SUNY/Albany with a degree in political science and then had taken a series of menial jobs. Currently he worked in a record shop. He hadn't lived at home since college, though his addresses were never more than eight or ten blocks from the family abode on State Street. This latter may or may not have meant something; Albany gays tended to live within walking distance of the bars and discos on nearby Central Avenue, and Billy Blount's unbroken proximity to his parents could have been coincidental. I'd find out.

The Blounts knew no names of their son's friends. They said his social circle was, they were certain, made up of "gay individuals," and they thought I might be acquainted with some of them. This was possible; gay Albany, though populous enough, was not so vast as San Francisco.

The Blounts gave me a photograph of their son. He was good-looking in a lean-jawed sort of way, with a broad, vaguely impudent smile, shortish dark hair, deep black eyes, and the obligatory clipped British military mustache. I thought, in fact,

that I had seen him around in the bars and discos. Given my habits and his, it would have been odd if I hadn't.

They provided me with Billy's current address on Madison Avenue, and a check for one thousand dollars, which I stuffed deep in my pants pocket. I said I'd report back to them within a week but that I had a few fiscal loose ends to tie up in mid-afternoon before I began work on their case. Stuart Blount walked with me to the door, shook my hand, made a point of squeezing my shoulder as he did so, and wished me "all the best of luck."

I had the feeling I was being used by these people in a way I wasn't going to like once I figured out what it was. Outside, the cold wind felt good. I ambled down State, turned the corner away from the park, and made for the bank.

2

Back on central i checked my service, which had a one-word message from Brigit: "books." I flipped through my desk calendar, picked a page in mid-December, and wrote: "Brigit– books."

The Times Unions for the past four years were stacked on the floor next to my file cabinet, and I hefted the top unyellowed half-dozen onto my desk. Starting with the Sunday, September 30 edition, I clipped all the stories on the murder of Steven Kleckner, which had been discovered on the morning of the twenty-ninth, and which now, six days later, Stuart and Jane Blount's renegade son stood accused of having committed.

The discovery story rated two columns on page one, a photo of the deceased, and a picture of two detectives standing in front of a house. Kleckner was clean-shaven and done up in a suit jacket and tie—in what looked like a high-school-graduation photo—with a bony, angular face and a big, forced, toothy

smile. He had a look of acute discomfort; maybe he'd hated high school, or maybe the photographer had just said, "C'mon, son, smile like your girl friend just said she was ready to go all the way," or maybe his shirt collar was too tight. High-school photos were always hard to read. The police detectives in the other photo looked grave, and one was pointing at a doorknob. No mention was made in either the caption or the story of the significance of this gesture. I made a note to "ck sig drnb." It was possible the doorknob was simply thought by someone to have been vaguely photogenic and redolent of criminal activity.

Steven Kleckner, aged twenty-four, the main story said, had been discovered stabbed to death in his bed at 7:35 the previous morning by Albany police. The department had received an anonymous call from a man who'd said only: "He's dead—I think Steve is dead," and given the address. Police had been admitted to the basement apartment on lower Hudson Avenue by the landlady, who lived on the first floor of the rundown brick building, one of the few in the neighborhood that hadn't yet been urban-renewed.

A long kitchen knife, its blade blood-soaked, had been found on the floor beside the bed on which the victim lay. There was no sign of a struggle having taken place or of forced entry into the "inexpensively furnished apartment."

Kleckner was identified as a disc jockey at Trucky's Disco on Western Avenue who had come originally from the village of Alps in Rensselaer County. He had lived in Albany for six years and was "a bachelor." The article did not mention that Trucky's was a gay student hangout near the main SUNY campus and that Kleckner was well known and well liked among the regulars there. Twenty years earlier the headline would have been YOUTH SLAIN IN HOMO LOVENEST, but discretion to the point of uninformativeness had set in at the Hearst papers. Or maybe it was just indifference.

The article did reveal that Kleckner, who had not worked at Trucky's on the fatal early morning but had spent most of the night there dancing and drinking with friends, was last seen leaving the bar around three a.m. "with a male companion."

A small sidebar contained remarks from people who knew

Kleckner back in Alps. His basketball coach said Kleckner was "a nice kid, polite, and kind of shy" who "didn't fool with drugs and didn't date much." The manager of a Glass Lake supermarket where Kleckner once bagged groceries called him "sort of bashful" but "reliable and well brought up." Kleckner's older sister, Mrs. Damon Roach, of Dunham Hollow, spoke for the family: "He was just a mixed-up kid, and he didn't deserve a thing like this. It's too late for Steven, but maybe other boys will learn a lesson from it."

A day later, on Monday, October first, the Times Union said police had identified the "male companion" as William Blount, of Madison Avenue, "son of a prominent Albany financier," and were seeking his whereabouts so that he could be questioned. The same article said the medical examiner had estimated the time of Steven Kleckner's death as five-thirty a.m. and had "stated his belief the victim died instantaneously from a single puncture wound to his heart." Also, for the first time, word was out: traces of semen had been found in Kleckner's rectum. No forthright speculation was offered on how the substance had found its way there, but Billy Blount, the murder suspect, was now identified as a "one-time gay activist" who had been chairman of the Albany-Schenectady-Troy Gay Alliance Political Action Committee in the early 1970s.

Follow-up stories over the next four days offered no new hard news, except that the DA's office now considered the evidence against Blount to be "conclusive," and a warrant had been issued for his arrest. Blount was being charged with second-degree murder.

The Times Union had not editorialized on the crime; moral inferences, for what they'd be worth, would have to wait. The paper did print a letter to the editor from Hardy Monkman, president of the Gay League Against Unfairness in the Media, taking the paper to task for its "insulting reference to a gay citizen's body" and including a "demand for equal time." Whatever that meant. The gay movement still had strength in Albany, but occasionally one of its leaders came forth with a public utterance espousing a notion and couched in terms of such sublime daffiness that gay men and women up and down

the Hudson Valley cringed with embarrassment or, as might have been the case with Billy Blount, said the hell with it and dropped out.

I slipped the clippings into a file folder which I marked Blount/Kleckner, then called Albany PD and learned that the detective handling the Kleckner murder was out of his office and wouldn't return until Monday.

I drove out Central to the Colonie Center shopping mall. At Macy's I picked out a black lamb's wool sweater and slipped it on under my jacket. I wrote out a check for forty dollars, signed it in a bold hand, and laid it on the counter in front of the bored clerk. He glanced at the check as if he'd seen one before, and then he glanced at me as if he'd seen one before. He looked familiar. I said, "Kevin—Elk Street?"

"My name is Kevin, but I live in Delmar. I don't believe we've met. No—no, I'm sure we haven't."

Like hell. "Sorry," I said. "I had you mixed up with a guy I once knew who'd drawn little valentines all over his buttocks with a ball-point pen. Inside the valentines were the initials of all the men who had visited there. It must have been another Kevin. Sorry. Funny story, though, isn't it?"

"H-yeah, ha ha."

The Music Barn record shop was along the main arcade of the shopping center, across from a long brick-and-blond-wood fountain that tinkled and hissed like an old toilet tank. Bernini in the suburbs. I spoke with the Music Barn clerk and was directed to the back of the store, where I found the manager opening up a carton of Donna Summer "On The Radio" LPs.