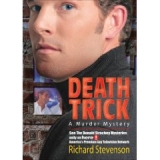

Текст книги "Death Trick "

Автор книги: Richard Stevenson

Жанры:

Слеш

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

My escorts and I trudged up the corridor, past the metal detector, through a doorway, and up a concrete stairwell. In the airport security office I was shown a metal chair and instructed to sit in it. I smiled, and sat. Bowman arrived twenty minutes later.

"His name's not Douglas! That's Strachey! That's the asshole who—!"

Bowman turned and told a man in a gray suit and blue tie that he wanted the airport sealed off immediately.

"Sealed off?" the man said. "Why?"

"I'll explain later, Pat. There's a murder suspect who came in on that American flight from Chicago. I'll bet my mother's sweet name on it. He came in with this guy. Al Douglas!" He shoved at my chair with his foot and it scraped a few inches across the floor.

I said, "As I explained to you last night, Ned, the killer is in Loudonville. Or in Albany. Stuart Blount knows where, and so

do the killer's parents. Their name is Storrs. Billy Blount was with me in Denver last night. We can both prove it; we were both seen there by a Denver police officer. Frank Zimka was killed in Albany last night by the same man who attacked Huey Brownlee and killed Steve Kleckner. His name is Eddie Storrs."

The man in the gray suit said, "Ned, we can't just seal this place off—not just like that. There's just me and two officers here. We'll need help from the sheriffs office or from your

department. Jeez, I'm sorry, but–" He made an apologetic

face.

Bowman had been watching me. I was trying to look confident and earnest but not too smug. He said, "Then let me use your phone, Pat. Can you do that this week, or will you have to make arrangements with the governor's office?"

The gray-suited man nodded toward the phone, turned, and stomped off.

Bowman phoned the DA's office and made noises about a "possible break in the Kleckner case" and asked that the assistant in charge of the case remain on call for the next twenty-four hours. Bowman said, "The Blount kid is back in town."

Then he called Stuart Blount and asked for a meeting. One was set up for half an hour later at the Blount abode on State Street. I was instructed to accompany him. I didn't object.

During the ride into Albany I repeated in detail what I'd told Bowman on the phone the night before, as well as everything else I'd found out over the past seven days and the conclusions I had drawn.

He said, "You misled me. You held out on me. You've committed a number of very serious offenses."

I said, "You are not just incompetent, you are willfully incompetent. I may file a taxpayer's suit. I haven't decided yet."

"You'd better redeem yourself in a hurry, Strachey. Your time has run out."

"So had you. So has yours. I have only your prejudices and intransigence to contend with. You've got a killer loose in your city."

"Thanks to you," he said. But he was only going through

the motions. He'd listened to my story, and he hadn't questioned it.

I said, "Where is Eddie Storrs?"

Bowman was beside me on the sofa, a foot of clean air between us so our thighs wouldn't touch and Bowman wouldn't have to arrest me for lewd solicitation. The Blounts faced us from their beautiful chairs and looked at me suspiciously.

"Have you found our son?" Blount said. "We'll tell him all about Eddie just as soon as he's in the sergeant here's custody. Is Billy in Albany, Mr. Strachey? I should think that for the expenses you've incurred in the past week—"

Now Bowman said it. "Mr. Blount, where abouts is this Eddie Storrs fellow? It might be helpful if I had a talk with him. Now I said might" He glanced at me. "I won't trouble the boy, just ask him a few questions that have been raised and are troubling my mind."

The missus gave me a steely look and went for her Silva Thins. Blount said, "Well, truth to tell, Sergeant, Eddie Storrs is in the process of rebuilding his life following many years of difficult psychological counseling. And in point of fact, I can't imagine a worse time to drag him into a complicated matter that can only, I should think, upset him and perhaps undo some of the good work that's been accomplished in regard to Eddie's life-style and much-improved mental outlook."

I caught Bowman's eye. He had the look of a man with a headache coming on. He said, "Where is the Storrs boy's family? Loudonville? Their names, please."

Jane Blount let loose. "Oh, really, Stuart—" She ignored Bowman and me and addressed her husband as if he were the one who was ruining her afternoon. "Stuart, I can't imagine what this is all about, but I have to insist that that boy's privacy be respected. After all these years of struggle and pain, and now with a new job and a lovely young wife—to have it all disrupted by dragging Eddie into this—kettle of fish! Well I, for one, will not abide it, and neither, I'm sure, will Hulton and Seetsy. It's all just too—deplorable!"

Bowman blithely pulled out a pad and wrote it down. Hulton Storrs. And Seetsy. Or Tsetse.

I said, "Eddie is married?"

"You wouldn't know about such things," Jane Blount snapped.

"I've read widely."

"You see, the thing is," Blount explained in his mild way, "Eddie Storrs has become a young man whom Jane and I are rather hoping will serve as a role model for our Billy, an example to emulate. Eddie is extremely happy and well adjusted in his new life, and we thought perhaps a short visit by Billy with Eddie and the nice girl he's married to would demonstrate to Billy just how fulfilling family life can be. It's not too late for Billy, and it's a life he might want to work toward. With professional help, of course. Jane's and my own example has never served that purpose, unfortunately, because we're older. It's the generation gap, if you get my meaning."

Bowman's words were, "The family is the bedrock of Christian civilization," though he looked at the Blounts in a way that suggested he might come to consider them exceptions to his rule.

I said, "Eddie Storrs killed Steven Kleckner. Last night he killed another man. He could—probably will—kill again. It's possible—likely—he's planning an attack on his next victim at the moment. Where is he?"

Bowman didn't move. Jane Blount gripped her ashtray. Stuart Blount looked at Bowman for help, saw that none was forthcoming, cleared his throat, and leaned toward us gravely. He said, "Hulton Storrs has invested forty thousand dollars a year for ten years in that boy's recovery. That is four hundred thousand dollars, only partially tax-deductible. Are you suggesting, Mr. Strachey, that in return for nearly half a million dollars, one of the finest rehabilitative institutions in America has turned Edwin Storrs from a faggot into a killer?"

"Your pal Hulton should have put most of his bucks into krugerrand," I said. "For a lesser amount he could have turned his son from a faggot into a wretched zombie with most of his memory blotted out. Mainly that's what those outfits manage to accomplish. But for four hundred grand—sure, that kind of money might come up with a killer. Apparently it has."

"Where's your evidence?" Blount said.

I explained. Blount scowled at his lap. Jane Blount sat bug-eyed.

When I'd finished, Bowman said, "It adds up. Where is he? Do you put us in touch with the boy's family, or do I waste thirty seconds tracking them down on my own?"

Stuart Blount removed an address book from his inside breast pocket and opened it. His wife got up abruptly and left the room.

Before we left for Loudonville, I used the Blounts' phone and called Timmy's apartment. No answer. I called his office; he was "out for the day." I checked my service and was given this message: "We're at a certain fitness center on Central Avenue." The tubs. Timmy probably had Blount locked in a cubicle with him and was reading aloud from Teilhard de Chardin.

I called Huey Brownlee, who was safe and just leaving the machine shop for my apartment, and then, at her office, Margarita Mayes, who said she was still staying with a friend in Westmere. Sears Automotive Center said Mark Deslonde had taken the day off and wouldn't be in until Monday. I phoned his apartment and got no answer; I thought, fine, he's still with Phil. I almost dialed Frank Zimka's number, and then I remembered.

During the fifteen-minute drive up Route 9 to Loudonville, Bowman was silent. I asked him if his police radio picked up Disco 101, but he ignored me. He'd phoned Hulton Storrs before we left Albany and arranged a meeting, but he'd held off explaining to Storrs the exact nature of the "serious matter having to do with your son Edwin" that Bowman said he wanted to "sift through." He sat in the driver's seat beside me, eyes fixed on the tarmac strip ahead of us. Once he said, "Goddamn Anglicans," and then he was quiet again. I supposed he was going to add Episcopalians to his long list of dangerous types.

Hulton and Seetsy Storrs lived in a commodious neo-Adamesque brick house on Hickory Lane overlooking a field of goldenrod. We parked on the gravel drive and rapped the silver

knocker on the big white front door with a rising-sun transom over it.

"Chief Bowman, so good of you to drive all the way out here. I'm Hulton Storrs."

"It's Sergeant, thank you. This is Detective Strachey. Pleased to meet you."

Storrs was tall, thin, and stoop-shouldered in a tweed jacket, black turtleneck, and brown woolen slacks. He had a long face with dark vertical lines of age, and the eyes behind his horn-rimmed glasses were red with fatigue. He walked like a man working hard not to topple. Storrs led us into a large sitting room that ran the depth of the house, with french doors at the far end opening onto the back lawn. Three chintz-covered couches formed a U in the center of the room around a cream-colored rug. On one of the couches two women sat together, the older holding the younger one's hand.

"I've asked my wife and daughter-in-law to join us," Storrs said and introduced us to Seetsy Storrs and Cloris Haydn Storrs.

Bowman said, "Coricidin?"

In a high, sweet, little girl's voice, the young woman spelled it. She had on a pretty blue dress, pink lipstick, and yellow hair tied in a bun with a white velvet ribbon. A rumpled Kleenex stuck out of her clenched fist. The older woman looked up at us out of a worn, tight, politician's wife sort of face with frightened eyes.

We sat.

"My son has left home," Hulton Storrs said. "Have you found him? Is he dead?"

The women froze.

"No," Bowman said. "Why do you ask that?"

The women closed their eyes in unison and exhaled.

"Eddie sometimes suffers from a loss of memory," Storrs said. "He forgets who he is and where he is."

Bowman said, "That shouldn't be fatal."

"Oh, it isn't that," Storrs said. "The difficulty is, when Eddie has his spells, he sometimes ends up in the company of bad characters—people who might do God knows what. Hurt the boy. This has occurred in the past—once in Indianapolis and on another occasion in Gary, Indiana."

I said, "Your son's no boy. He's twenty-seven years old. He's a man."

"You don't know Eddie," Storrs said. "Eddie has only just begun to mature. You see, his development was retarded somewhat, slowed down, by a mental problem. You may or may not be aware that Eddie has spent most of the past ten years in a psychiatric rehabilitative center in Indiana. The boy has had his troubles, I'm afraid."

These people would have called the tiger cages at Con Son Island a correctional facility.

Bowman said, "Eddie may have committed a crime. It's urgent that I speak with him. Do you have any idea where he's gone? When did he leave?"

The two women clung to each other, looking wounded and well groomed, like a couple of Watergate wives. Storrs said, "Committed a crime? What do you mean by that, Captain?"

"Sergeant. It's Sergeant, thank you."

Bowman laid it out. As he spoke, the women wept and shook their heads. Hulton Storrs sat slumped with his chin on his chest, like another victim of the son he had "cured."

When Bowman had finished, there was a silence. Then Storrs looked up and said quietly, "Our plans seem not to have worked out."

Bowman said, "It sure looks like they haven't, Mr. Storrs. You and your loved ones have my deepest sympathy, I want you to know that. Now, sir, would you please tell me when your son left home, as well as the circumstances of his leaving?"

Hulton Storrs told us that his son had arrived home from his job as an "accountant-in-training" at Storrs-Lathrop Electronics in Troy the previous evening at six-thirty. He dined with Cloris in their "cottage," a converted stable on the grounds of the Storrs's estate. After dinner Eddie said he was "going for a ride" and drove off in his new gold-colored Olds Toronado. He'd "gone for rides" often in the past month, Storrs said, sometimes returning in the early-morning hours. Eddie's wife reported tearfully that the Olds was a wedding gift from the Haydns and that her husband "was just out of his gourd over that ace car of his."

Eddie Storrs had not returned at all on this morning,

though, and the family had been discussing notifying the police when Bowman telephoned. They thought Bowman would be bringing news of Eddie's whereabouts and condition, and feared that Eddie might have been harmed by "persons with masochistic tendencies," persons of the sort to whom he had been drawn during two month-long escapes from the Lucius Wiggins Psychiatric Rehabilitation Center in Kokomo, Indiana.

How these "masochists" were going to harm his sadistic son, Storrs didn't make clear. Maybe Storrs thought that in Indiana water went down the drain counterclockwise. It was the self-delusion wrought by love—or some grotesque permutation of love that I'd run into before but guessed I'd never understand.

At Bowman's request, the Storrs family led Bowman and me out to the young couple's cottage, where we discovered two knives missing from a velvet-lined wooden box of Sheffield cutlery. We also found—in a cardboard box full of Eddie Storrs's Elwell School mementos—a photograph of Billy Blount. The picture was taped to the front cover of Blount's phone book, the one stolen the previous weekend from his apartment.

Of the four phone numbers handwritten by Billy Blount on the back cover of the book, two—the first and second names, Huey's and Chris's—had penciled checkmarks after them, apparently signifying unsuccessful attempts on their lives. The third name, Frank Zimka's had been Xed out. The fourth name on the list, circled in red, was Mark Deslonde's.

23

I PHONED PHIL'S APARTMENT, WHERE DESLONDE WAS STAYING.

There was no answer. I phoned Deslonde's apartment, where no one was supposed to have been staying. The line was busy. It was five after seven. On Friday night Deslonde wouldn't

be going out until nine or ten. Bowman phoned Albany PD, and we raced out to the highway.

Bowman did a steady sixty-five on the two-lane road, weaving in and out of the Friday-evening traffic in his unmarked Ford. I said, "Haven't you got a siren on this thing, like Kojak? Christ!"

"Shut up."

We hurtled into the city, through Arbor Hill, up Lark, veered right and shot up past the park. Traffic on Madison was blocked off from New Scotland to South Lake. We eased around the barricade. Two Albany police cruisers were double-parked, blue lights flashing, in front of Deslonde's building, an old four-story yellow-brick apartment house. A crowd was gathering across the street from the building, and people were looking up. A figure sat perched on the fourth-floor window ledge in the center of the building. The figure was silhouetted against the light of the open window behind him, and at first I thought it was Frank Zimka, but of course it wasn't.

A fire engine and ambulance were parked up the street, and six men holding a safety net stood under the spot where Eddie Storrs was perched. The only sounds were from the crowd, speaking in subdued voices, and from the staticky sounds of the police radios. Twenty yards up the street, blocked in by the idling fire engine, sat the gold-colored Olds.

A patrolman explained to Bowman what had happened. "When we got here, Sergeant, the perpetrator—that guy on the windowsill—was in the hallway outside the Deslonde guy's apartment. When we came up the stairs, he must have seen us coming, and he opened up the window and climbed out there. He said not to get near him or he'd jump, so we backed off down the stairs and called the rescue squad. He's been up there for ten minutes, I'd say. An officer is in the stairwell behind the guy trying to talk him in, but he won't talk back, and if anyone gets near him he lets go of the window frame. That's about what we've got. You got any ideas? The captain's on his way."

Bowman said, "Where's Deslonde?"

"We haven't seen him," the cop said. "The door to his apartment looks like it's closed, but we can't get close enough to see for sure."

"Is there another entrance to the apartment?"

"The super says no."

"Get a ladder up to a side window," Bowman said. "And get a second ambulance out here. Cut through the window if you have to—but don't bust in, it'll be too noisy and might spook the jumper."

Bowman reached through the car window, pulled out his radio mike, and asked the dispatcher to dial Mark Deslonde's phone number and to patch Bowman through. We heard the clicks of the 434 number being dialed, and then the ringing. It rang twenty times before Bowman said, "Okay. Okay, that's enough."

He looked at me ruefully and shrugged. We stood there for a moment considering the possibilities, and then our eyes went back up to the figure on the ledge.

I said, "I'll get Blount. I'll need a car."

Bowman nodded and instructed a patrolman to take me wherever I wanted to go.

I said, "Ten minutes."

"In fifteen minutes," Bowman said, "we're going up there whether the kid jumps or not. The guy in the apartment comes first. There's no sign of him—he could be hurt in there."

We drove slowly up Madison until we'd rounded the corner onto Lake, then sped north toward Central and the baths.

I found them lounging on a cot in a closed cubicle, towels draped over their naked laps, surrounded by orange-juice cartons and Twinkie wrappers and looking sheepish. Teilhard de Chardin was nowhere in evidence. The ambiance did include, however, a certain distinctive combination of aromas.

I said, "We've found Eddie. You've got to come right now. Get dressed."

Timmy said, "No, first you're supposed to say, 'Holy smoke, I hope I'm not interrupting anything.'"

"Eddie Storrs is threatening suicide. Mark Deslonde may be in trouble. Hurry up. Move."

They moved.

A ladder was being raised up the right side of Deslonde's building from the narrow yard that separated it from an old

second-empire Victorian house. Eddie Storrs still sat motionless on the window ledge in front. Billy Blount stood in the shadows of the autumn foliage and gazed up at him. Up the street a second ambulance moved quietly into position behind the first.

Phil had arrived. He was arguing plaintively with a uniformed police captain now on the scene who was not allowing anyone to approach the yard with the ladder except "family members."

I said, "He's Deslonde's best friend," and looked at Bowman, who saw what I meant.

Bowman said to the captain, "He's the guy in the apartment's boyfriend, Lou. It's up to you."

"Family members only," the captain said blandly. He turned and walked away.

Phil started to lunge, and I stepped between them. Timmy and I wrestled Phil back into a yard across from Deslonde's building. He collapsed onto the ground and sat there, flushed, teeth clenched, his chest heaving.

Timmy stayed with Phil, and I walked back into the street where Bowman was standing. He said, "I make it a practice never to argue with a captain," and looked away.

I said, "That's not the way it happened. You were petty, and callous."

He looked back at me with hard eyes. "You people are going to make an incident out of this, aren't you? Blow it out of proportion."

I said, "I think so, yes."

"I'll deal with you later, Strachey. For a man who's broken as many laws as you have in the past week, you're acting pretty goddamned pushy with me. I want you to know I've just about come to the end of my rope with you."

"Do you want your defendant in the Kleckner case alive or dead?"

"Alive," he said. "It's expensive for the taxpayers but it's tidier on my record."

"Fine," I said. "I'll bring him down for you in return for an apology to Phil Jerrold, the guy you just fucked over in a particularly vicious manner."

He snorted and shook his head in disbelief. He turned toward the spot where Billy Blount was standing under a tree and gazing up at the man on the ledge. "Hey, come over here! You—Blount!"

Billy Blount walked into the middle of the street to where we stood.

I said, "Don't do what he says."

Bowman said, "Billy, you and I have got to go in there and say something soothing to your friend there. It might take awhile, so let's just relax and go up and sit on the stairs for a time and let the fellow hear the sound of your voice. Let him get used to it. Then we'll see what we can make happen. You got me?"

I said, "Don't go. Not until the sergeant here has offered an apology for his homophobic cruelty toward a friend of ours—a friend of Mark's."

In the side yard a patrolman with a tool kit strapped to his back was moving up the ladder.

"Come on, Billy, we've got to get that troubled lad safely onto terra firma. Let's go, kid."

Bowman moved toward the building. Blount stood still.

Bowman turned around, glowering. He said, "You're both under arrest."

We looked at him.

He said, "You, William Blount, for suspicion of murder. You, Donald Strachey, for aiding a fugitive from justice. I'm obliged to remind you that you have a right to remain silent, you have a right to—"

"Bi-l-l-leeee!" The voice sliced through the night. The crowd froze. The man on the ladder stopped and listened.

This time the figure raised one arm from the window frame. "Bi-l-l-l-eeeee!" The crowd gasped, and someone behind us said, "Oh, God."

Blount yelled, "I'll be right up, Eddie! Hang on! "I'll be up!"

Blount trotted across the street, up the brick walkway, and into the building. A minute later two arms were wrapped from behind around the figure on the ledge. The figure began to turn as if on a pinwheel, and then it doubled up and disappeared through the window.

We charged into the building and up the stairs. Blount and Storrs were sitting beside a blue gym bag on the floor of the fourth-floor landing, their backs against the wall under the window. Blount was holding Storrs's hand. They hardly seemed to notice us banging on Mark Deslonde's locked door.

There was no response from inside the apartment. Two firemen bounded up the stairs with axes; Bowman and I and three patrolmen stood back. I could hear the radio blasting away inside. Disco 101—the Three Degrees' "Jump the Gun." After three well-placed blows the door splintered and fell away.

The living room was empty. The face of the man on the ladder was visible through the window. We moved into the bedroom and found no one. A second set of stereo speakers carried the roar of the music into the room where we stood. Bowman said, "Somebody shut that goddamn thing off!"

The bathroom door opened. Mark Deslonde stepped out in his nylon briefs and stared at us with the most astonished look I'd ever seen on a face.

I said, "Jesus! Are you all right? Where the fuck have you been?"

"I've been trimming my beard. What is this? What the hell is going on?"

"Trimming your beard? For an hour? For a fucking hour?"

Deslonde shrugged, tilted his head, and grinned.

24

"You've got a lot of nerve coming in here, strachey. Because we're such nice guys, the DA and I decided during the excitement last night not to go to the trouble of prosecuting you and your pal Blount, and now you waltz in here like you owned the goddamn city of Albany and start badgering me and asking for favors. I've run into some pretty deluded perverts over the

years, but, Jesus' mother, you take the cake, Strachey, you surely do."

I said, "What a crock. You owe me a big one, and you know it. I just want to borrow the thing overnight. You'll have it back first thing Sunday morning. By noon, anyway. Or one."

He shifted in his chair and caused the holes and nodules on his face to move around. "I'd have to know your intended use for the device," he said. "That thing is worth a lot of money, and if it got damaged in any way, they'd make a note of it and take it out of my pension when that holy day comes, and that pension is already so piss-paltry the wife and myself will probably end up in some trailer parked by a meter on Central Avenue. Now, what the hell are you gonna do with it?"

"I can tell you this much, Ned. The device will be used in a manner your department will approve of entirely. I'm talking about law enforcement. It will be used to collect evidence against a felon. I plan to provide the DA with another warm criminal body for Judge Feeney to pounce on and gobble up. And if you'd like, I'd be happy to mention your name in connection with the apprehension of this disgusting public menace."

He cringed. "You can skip the last part."

An hour later, before I had lunch with Timmy at his apartment, I phoned Sewickley Oaks.

"This is Jay Tarbell, calling for Stu Blount. Mr. Blount's son William has been located, as you may know, and Mr. Blount wishes now to proceed with the boy's treatment. He would appreciate your picking up the boy late tonight, and I'd like to discuss the arrangements—the boy is rather distraught, I'm afraid, and might put up some resistance. I'm sure, though, that your staff can come prepared for any eventuality."

"Oh—I see. Well, Dr. Thurston has stepped out, but I know the doctor thought perhaps Mr. Blount might have changed his mind. I mean, considering what happened last night—we saw the TV reports, and we thought—"

"Not at all, not at all. The boy is no longer under suspicion of murder, of course, but, sad to say, young William is still queer as a three-dollar bill, so to speak, ahem. And you do have Judge Feeney's order in hand, do you not?"

"Oh, yes—"

"As well as the substantial first payment of Dr. Thurston's fee."

"Oh, certainly—"

"Well then, let's get on with it, shall we? Let's lay out a plan. Now I must tell you that young Blount has altered his appearance and that he has assumed an alias. I'll be calling later tonight with further details, but for now, let me just pass on to you Stu Blount's instructions...."

Saturday night at Trucky's. After a warm-up at the Terminal, we drove out Western just after eleven. As we went in, Cheryl Dilcher's "Here Comes My Baby" was on. Truckman was at the door, drink in hand, and I told him I'd like to see him in his office, that I had an apology to make.

He smiled feebly and said, "Sure, Don, sure. Gimme ten minutes."

We ran into the alliance crowd and learned that the judge had denied a restraining order against the Bergenfield police, and that Jim Nordstrum, out on bail, was planning to close the place if it was raided one more time. Despite the absence of any discernible warm feeling for the Rat's Nest and its approach to gay life, there was real anger among the movement people over the sour indifference of the legal establishment toward the harassment of a place that detracted from the moral fitness of no one who chose not to go there. The human machinery of the law was smug and petty and substantially corrupt; that was what hurt. No one could figure out what step to take next, and I did not tell what I knew.

I went looking for Mike Truckman, found him, and ushered him almost forcibly into his office.

I said, "I did think you had something to do with Steve Kleckner's death, Mike. It was mainly because of the company you keep. And your booze problem didn't help—you've got one and you'd better do something about it fast. Anyway, I was stupid and wrong-headed, Mike, and I hope you'll forgive me."

He raised his glass, tried to smile, and set the glass down. "Forget it, Don. Shit, I guess you had your reasons. Let's pretend it never happened. I'm game if you are. We need one

another, all of us. Gay people can have their differences, sure, but when push comes to shove, we gotta stick together, right, buddy?"

"That's well put, Mike. Which brings up a painful but related matter."

He'd been glancing at the manila envelope I'd carried in with me, and now he watched me open it and spread the photos out across his desk. He sat blinking, his mouth clamped shut, and peered at them.

I said, "You know what you have to do, don't you? If you're going to get your head together and come back to us, Mike, you've got to start by dealing with this shit."

He managed to get his mouth open far enough to rasp, "Yeah. Yeah, I guess I know."

I took off my jacket and shirt. I removed the Albany PD microphone and wires and recorder from my torso and placed them on the desk alongside the photos of Truckman handing money to the Bergenfield police chief and his plainclothes associate, in payment for their raids on the Rat's Nest.

I said, "Before I show you how to work this thing, I'd appreciate your answering a couple of questions."

He blinked boozily at the display on his desk and said, "Oh, God."

I called Sewickley Oaks from a pay phone up the road from Trucky's. Then I walked back to the disco and danced with Timmy, among others, until closing.

The usual crowd was on hand—Phil, Mark, Calvin, the rabbi—and while most people were subdued at first, only just beginning to recover from the shocks of the past week, one by one each of us gave in to the New Year's Eve atmosphere that gay life can, with luck, produce two or three times a week. By the time Billy Blount arrived with Huey Brownlee at two-thirty, the mood was entirely festive, even celebratory. The DJ played "Put Your Body In It," and everybody did.

At four-forty Timmy and I crouched behind the pile of tires next to the Bergenfield police station. We watched while Mike

Truckman handed over a roll of bills. Timmy took more pictures. The three men lingered longer than they had the last time we'd watched this scene unfold; Truckman was making sure everyone's voice was recorded, that he got it all.