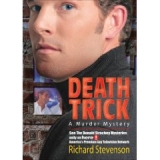

Текст книги "Death Trick "

Автор книги: Richard Stevenson

Жанры:

Слеш

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

before he'd opened his bar two years before, and he'd brought his tastes, or habits, of office decor with him: gunmetal gray desk, filing cabinet to match, steel shelving along the wall. The bass notes from the speakers outside the door bumped and reverberated into the little room and made the metal shelves sing.

I said, "I feel like I'm in the basement of the Reichschan-cellery. I hope you're not going to offer me a cyanide tablet."

The crack was ill-timed, and Truckman did not laugh. He sat behind his desk, made further use of his half-full glass of what smelled like bourbon, and I hoisted myself onto a stack of Molson's crates.

"Whadda you wanna know?" Truckman said in a boozy-gravelly voice. I'm cooperating with everybody on this thing, but I don't know what the hell else I can tell you. Christ, this fucking thing is just dragging on and on. Christ, I dunno. What am I sposed to do? Christ, I dunno. It's just a tragedy, that's what it is, just a fucking terrible, terrible tragedy."

He was drunk, and it had changed his personality from the one I knew. I remembered Truckman as a serious man, and sometimes agitated, but never morose and confused. I doubted that he'd made a habit of this. People who ran successful bars stayed sober. He brought a dirty white handkerchief out of his back pocket and mopped the sweat from his forehead and neck. He had a big, craggy face with a wide, expressive mouth and would have been matinee-idol handsome if it hadn't been for his eyes, which were cold gray and ringed with puffs of ashen flesh.

I said, "I'm sorry, Mike. I'm sure this is rough. Were you and Steve Kleckner close?"

"Whaddya mean, 'close'?" A sour, indignant look. "Sure, we were close, that's no secret. Christ, Steve looked up to me, you know? What I'm saying is, Steve respected me for how I was so up front about being gay and how I always did so much for the movement—one hell of a lot more than the other bar owners did, the assholes. Steve thought I had—Christ, you know– principles."

He grimaced. A rick of milkweed-color hair stuck out over one ear, and I wanted to pass him my comb.

I said, "I didn't know Steve. What was he like?"

He squeezed his eyes shut with his free hand. "A nice kid," Truckman said, shaking his head. "Oh, such a nice sweet kid Steve was. But—naive. God, was that kid naive! Steve was naive, but he was learning, though, right? Steve was young, but he was catching on. We all have ideals, right? But you've gotta be tough in the way you go about it. A means to an end, right?"

He was beginning to slur his words. I said, "Right."

More bourbon.

I said, "Mike, you're drunk."

He shook his head. "Nah, I'm drinking but I'm not drunk. Anyways, Floyd's out there, the doorman. Floyd can run the place if I feel like taking a drink. Floyd can do it, right?"

I nodded. I asked him why anyone would want to hurt Steve Kleckner.

He rolled his eyes at some imaginary companion off to my right. "Christ, how would I know the answer to that? You'll have to ask the sonovabitch who did it, right? If the goddamn cops ever catch up with the little shit."

"You mean Billy Blount?"

"Hey, the Blount guy did it, dinnee? I thought everybody knew that—the kid Steve left with here that night. With here. Here with."

"Did you know Blount?"

"Nah, but I saw it happen—saw Steve and that little shit turn on to each other. I mean, don't get me wrong, right? I was glad to see it, honest to Christ, I was. I was glad to see Steve being so up for a change. Christ, moping around here the way he was, I just wanted to pick Steve up and shake him."

"How come he'd been down?"

Truckman emptied his glass and brought a new bottle of Jim Beam from his desk drawer. He kicked the drawer shut and filled his glass as well as a second one. He said, "Join me."

"I've got a stein of your fifty-cent horse piss outside. Thanks, I'll stick with that. Why had Steve been depressed?"

"Dunno. Maybe his rose-colored glasses fell off." He drank.

For an instant I wondered if Kleckner had actually worn rose-colored glasses, like Gloria Steinem's. It wouldn't have been unprecedented at Trucky's.

I said, "Had he talked about it?"

"Nope, unh-unh." He poured the drink for me that I'd declined.

"Had you ever seen Steve with Blount before?"

"Not that I remember. The cops asked me that. Fucking cops."

"Why 'fucking'?"

"Oh, you know, Don. You should know. Cops."

"Have they been hassling you?"

"Nothing to speak of. Drink up."

"Vigorish?"

"Nah. They fucking hadn't better try."

"What did you tell the cops about that night?"

"What all I knew, why shouldn't I? That Steve and the Blount kid danced, and horsed around, and left about an hour before closing. Shit, Steve could of done a lot better than that kid, a fucking lot better. And now look what happened! It's just a tragedy, that's what it is, a fucking terrible, terrible tra-guh-dee."

His eyes were wet, and he tugged out the hankie and wiped his face. Then, more bourbon. He said, "Don, you're not drinking."

I sipped. "Do you ever wish you'd stayed with the state, Mike? You had a nice neat, clean life down there."

He snorted messily. "Hah, that's all you know! At the department it was everything but murder. Hell, no! I'm doing what I wanna do, Don. And no way—no way—am I gonna lose it, right? You wouldn't. No way, baby."

I said, "Business looks good."

"Yeah. S'good." He gazed down morosely at his drink.

"I want to talk to your bartender after closing."

"S'up to them. Floyd'll be locking up. I'm cuttin' out at four."

"Heavy date?"

"H-yeah. Real heavy."

"The cute number in the witty jersey?"

"Nah," Truckman said. "Not him. He's for later." He shut his eyes and laughed bleakly at some private joke.

"Well, I suppose you could do worse." "Oh, I do-ooo do worse." He gulped down the rest of his drink. "I sho nuff do. Hey. Don. How 'bout a drink?"

I guessed Truckman knew more about Steve Kleckner's recent life than he'd told me, but he was in no condition to be reasoned with, or pressured, or led. After Truckman's office the stench of smoke, poppers, and hot sweat outside it was a field of golden daffodils. I found Timmy at the bar talking—shouting– to a sandy-haired man of about thirty in a plaid flannel shirt.

Timmy leaned up to my ear and yelled, "I've got one!"

"One what?"

"One friend of Billy Blount's. Don, this is Mark Deslonde. Mark, Don Strachey."

He had soft brown eyes, a fuzzy full beard, neatly trimmed, and a tilt to his head that was angled counter to the slant of his broad smile. I didn't know whether he practiced this in front of a mirror, but it was devastating, and if Timmy hadn't been there it would have had its effect on me. Not that it didn't, a little.

I said, "Can we go somewhere?"

He smiled again and said okay and slid off his stool, and as we turned toward the door, Timmy cupped his hand over my ear and said into it, "You can do me a favor one of these days."

I said, "See you around—Tommy, wasn't it? I've really enjoyed myself and I hope we run into each other again sometime." I kissed him on the forehead. He laughed lightly.

Deslonde and I went out and sat in the Rabbit. The air was frosty, and a cold, luminescent half-moon hung over the motel up the road and across Western from Trucky's parking lot.

"You're friend is nice," Deslonde said, still grinning. "Is he your lover?"

"Sort of," I said. What the hell was I doing? "Well, yes. He is. We don't live together."

"That's smart. It makes discretion possible. I lived with my ex-lover for three and a half years. It was great for the first two. Until one of us started fooling around once in a while, and because we were living together, this was noticed. Nothing heavy, right? Just the occasional recreational indiscretion. But

Nate was Jewish enough, or insecure enough, to believe in monogamy, and that was the beginning of the end."

I said, "Do you have regrets?"

"Sure."

"Timmy says you're a friend of Billy Blount's."

"Yes, I know Billy. Your lover—whom you don't live with– says you're a detective. But not a cop, right?"

"Right. Private."

"Then you'd have a license."

I stretched out and dug my wallet out of my hip pocket. He studied the laminated card, and I put it back.

Deslonde said, "Smoke?"

"Love it."

He took a joint from his shirt pocket and lit it. We passed it back and forth while we talked.

"I'm working for Billy's parents," I said, determined to concentrate on something other than Deslonde's face. "They want to help him."

"I'm sure they do," Deslonde said evenly. I couldn't tell if he was being sarcastic.

"How do you know Billy?"

"My old roommate and Billy were involved for a couple of months, before Dennis freaked out and took off for Maine. Billy and I kept running into each other in the bathroom in the morning, and one day I gave him a lift out to Colonie. I work at Sears."

"Sportswear?"

"Automotive supplies."

Strachey, you ass. "Right," I said. "Billy works at the, ah, Music Barn."

"I live right up the street from Billy on Madison, and he started riding out to Colonie with me regularly. Sometimes we went out together, or with other people, out here or to the Bung Cellar. We got to be pretty good friends after a while. Billy's really one of the more stimulating people I know and quite enjoyable to be around. In fact, I've become very fond of Billy over the past few years. There's nothing sexual in the relationship; it just didn't work out that way. Billy and I talked about that once. We both found each other attractive, but sometimes

the chemistry just isn't there, right? And then other times it is." He looked at me and grinned.

"Yeah," I said. "Funny how that works." I could feel the damn thing stirring. I said, "Where do you think Billy might be?"

"I have no idea."

"Do you think he's innocent?"

"Yes. Of course he is."

"How can you be that certain?"

"Because I know that Billy hasn't got a violent bone in his body."

"Uh-huh." I shifted, tried unsuccessfully to cross my legs. "I've gotten the impression that Billy is rather an angry young man. How does he let it out?"

Deslonde laughed. "Yeah, Billy is not one of the more relaxed people I know. What he does with all that indignation is he runs off at the mouth a lot. He can bend your ear for days on end about the world's four billion homophobes. I'm a realist myself—I told him maybe he ought to shop around for another planet."

"Maybe he's the realist. We seem to be stuck on this one."

He rolled down the window and flipped the roach onto Trucky's gravel drive. He exhaled and said, "For some of us the realistic thing is to find a way to eat and pay the rent. Try coming out as a radical faggot when you spend thirty-eight hours a week at Sears Automotive Center. I don't mean to sound melodramatic, but I thought you'd understand that. Or are you independently wealthy?"

He looked at me with his beautiful skewed smile again, but this time there was a hardness in his eyes. I wanted to do something to show him how I really felt about him. I shifted position again.

"I know what you're saying," I said. "There's neurotic secretiveness, and then there's discretion. I am not opposed to discretion. I've even been known, from time to time, to indulge in it myself."

What had I said? He'd been watching me, and now suddenly he burst out laughing, a big robust ha! ha! ha! ha! He gave my thigh a quick squeeze and then, still smiling, lit another joint.

I said, "About Billy Blount—remember him? Billy Blount?"

"Oh, right. Billy Blount. Let's talk about Billy some more." He grinned and passed me the joint. Our fingers touched.

"What about, uh, Billy's parents? How was his relationship with them?"

"They must be a pair," Deslonde said. "I've never met them, but Billy talked about them sometimes, and they sounded like real horrors. Tight-assed old family types. He wasn't crazy about them, and Billy was frustrated with the way they hated his being gay. But I wouldn't say they really preyed on his mind much. He just stayed clear of them, and that made life easier."

"They said he brought a trick to their house last month."

He shook his head and laughed once. "Oh, boy, what a screw-up. I'd asked to use Billy's apartment that night—my straight cousin was job hunting in Albany and staying in mine, and I had a friend I was going to sleep with coming up from Kingston—so Billy said I could have his place and he'd take his chances in the park. It was one of those gorgeous hot nights, and you knew everybody'd be out. So he meets this hunk from Lake George, see, and he's really turned onto this guy, but they've got no place to go. It was dumb—Billy knew it—but they went to the Blounts' place, which was right across the street. His parents weren't supposed to be back from Saratoga until Labor Day, and—well, you know the rest. Bingo."

"No, actually I don't. I was wondering what they managed to accomplish in the way of sexual bliss on that mahogany museum piece?"

He looked uncomprehending. "Come again?"

"They spent the night on Mrs. Blount's antique sofa. Or so I've been told."

"That's crap," Deslonde said. "They spent the night in Billy's old room. They were downstairs smoking and about to leave when the Blounts busted in with guns blazing. They were pissed, and Billy really was embarrassed. I don't think he's seen them since."

"So his relationship with his parents was strained and unhappy. But there was nothing about the relationship that struck you as—a little weird?"

"Weird? No. Awhile back—a long time ago, it must have

been—the Blounts did something that still makes Billy furious when he thinks about it, something that hurt him a lot. But he never told me what it was. It was something so painful he couldn't even make himself talk about it. But since I've known him he hasn't been bothered by them very much. It's as if they hardly exist."

Another new perspective. Why was I surprised? It was nearly always like this, Rashomon with a cast of sixteen.

I said, "I've got to find him and talk to him. He hasn't been in touch with you?"

"No, I wish he would. I'd like to help him."

"Who are his other friends? Somebody might know something. Has he ever mentioned out-of-town friends?"

"Here in Albany there's a guy named Frank Zimka who Billy sees once in a while. We've all gone out together a few times. He lives off Central—Robin or Lexington, I think. Sort of a weird guy, actually; he deals dope, and I get the idea he hustles. I could never figure out what Billy saw in him, and when I tried to find out, Billy didn't want to go into it. He just said something like, 'Oh, Frank can be fun sometimes.' Except if Frank was ever a barrel of laughs or whatever it is he has to offer, it definitely was not in my presence.

"Then there's a black guy over in Arbor Hill Billy sleeps with once in a while. I met him a couple of times, too, and they seemed to have a nice simpatico relationship. Nothing very intense, but nice. His name is Huey something-or-other. He's a construction worker or something and he's into martial arts. I think it's Orange Street he lives on.

"Out of town, I don't know. Billy had some radical gay friends once who live on the West Coast now, I think, and he might be in touch with them. When he quit the movement in Albany—the guys here are too wishy-washy for Billy the revolutionary—he talked about moving out to California, but by then his friends' organization, whatever it was, had fallen apart, so he didn't go. I don't know what their names are out there."

Frank and Huey were two of the first names written on the back cover of Billy Blount's phone book. Along with Deslonde's and one other.

"Did he ever mention somebody by the name of Chris?"

"No," Deslonde said, trying to remember. "I don't think so. Who's he?"

"I don't know. A name Billy wrote on his phone book. And a number."

"Call him up. He might be helpful. Or cute. And discreet." He chuckled.

"I will," I said, shifting again. "What about an Eddie? This would be someone out of Billy's past he'd be excited about running into again."

Deslonde shrugged and shook his head. "Unh-unh. Never heard of him. No Eddie."

"You mentioned your old roommate. Dennis, was it?"

"Dennis Kerskie."

"How long ago did he leave Albany?"

"More than two years ago—almost three. Dennis went off to the forest in Maine to live off berries and write his memoirs."

"Was he an older man?"

"Twenty-two, I think. He and Billy were a hot item for about two months until one day Dennis suddenly decided to purify his body and give up french fries, Albany tap water, and sex. He'd read a leaflet somebody handed him in the Price Chopper parking lot, and his and Billy's relationship deteriorated very rapidly. Dennis left town about two weeks later, and I don't think Billy ever heard from him again. I know I didn't."

It was ten to four and people were starting to drift out of Trucky's and head for their cars.

"Just a couple of other things. Were you with Billy the night he met Steve Kleckner?"

"For a while, I was. I gave him a lift out here, but then he got this heavy thing going with the Kleckner guy, and when I was ready to leave around one, Billy said to go ahead, he had a ride. I told all this to the police. Should I have?"

"It happened. I'm sure they got the same story from other people, so don't sweat it. How was Billy acting that night? Unusual in any way?"

"No, I wouldn't say so. He looked like he was having a good time. Actually, so was I. I'd met this tall number named Phil and went home with him. Real nice. Somebody I wouldn't mind running into again."

"Blond, with a squint?"

"That's Phil. Do you know him?"

"He's at the Bung Cellar tonight. He'll probably end up in the park. Another fresh-air freak."

Deslonde looked at his watch, then did his head-smile thing. "Maybe this night won't be a total wipeout after all."

I gave him a quick, tight smile. "Right. It's early." I hiked out my wallet again and gave him my card. "Do Billy a favor and call me if you hear anything, okay?"

"Business cards. That's a new twist." He did it again.

"I do this for a living."

"I’ll bet you do."

He got out of the car, then leaned back in through the open door. He smiled and said, "See you around, Don. Meantime, don't do anything discreet."

I'll check it out with you before I do," I said. "You're the expert."

He laughed. We shook hands, and he shut the car door. He walked toward the other side of the parking lot. He looked back once and grinned. I watched him go and sat for a minute concentrating my mind on a bowl of Cream of Wheat. Then I went inside.

Timmy was just coming off the dance floor. "Where did you go to talk? The Ramada Inn? Mark has a way about him, doesn't he?"

I said, "He was helpful. How did you find him?"

"He found me. I was asking around about who might know Billy Blount when Mark walked up to me and said, I don't know where you came from, but I love you.'"

"He didn't."

"You're right, it was different. I was standing by the DJ's booth, and he very shyly edged up and asked if I'd like to dance. I acquiesced."

"You raise acquiescence to a high art"

"I do?"

"One of us does. Whichever."

The music stopped. The thirty or forty people left in the place began drifting toward the front door. Fluorescent lights came on, turning all our faces a hideous gray. People walked faster. Mike Truckman moved unsteadily toward the cash

register, removed a wad of bills from under the tray, stuffed it into his jacket pocket, and exited with the crowd.

I talked with the bartenders while they gathered up glasses and ashtrays and empty bottles. They added little to what I knew. On the night before Steve Kleckner was found dead, Blount and Kleckner had danced and drunk together, seemed to everyone to have hit it off famously, then left Trucky's around three. The bartenders noticed all of this because Steve Kleckner had been depressed and preoccupied the previous two weeks—Kleckner had refused to tell anyone why—and with Billy Blount, he had snapped out of that. No one had seen them together before.

None of the bartenders knew Blount except by face and first name, but they all knew Kleckner. None could think of anyone who particularly disliked Steve Kleckner, who invariably was described as happy-go-lucky and a real nice guy. Not helpful. I did learn, however, that the person who knew Kleckner best was an ex-roommate named Stanley Loggins, who lived with his lover on Ontario Street—and that Steve Kleckner had once had an affair with Mike Truckman.

4

I WAS UP BY TEN. TIMMY SNORED LIKE A MASTODON WHILE I RAN

four eggs and a pint of orange juice through the blender. I showered, found some of my clothes among Timmy's clean laundry, left a note, and drove over to Ontario Street. My job was to find Billy Blount, but it wasn't going to hurt if I learned more about the sort of man he'd been attracted to. In fact, I guessed there were even better reasons for looking into Steve Kleckner's life, but I didn't know yet what they were.

Stanley Loggins, in green chinos and a lavender T-shirt, was pixielike, with bright pink eyes and buck teeth. His lover, Angelo, was big and beer-bellied and had hands like hair-

covered coal shovels. They sat side by side on an old brown sofa with antimacassars marching up and down its back and arms, a Woolworth's Mary-with-a-bleeding-heart hung on the wall above. Angelo eyed me suspiciously and swigged from a quart bottle of Price Chopper creme soda while Stanley told me about Steve Kleckner.

"Yeah, we roomed together for two years," Loggins said, his girlish voice cracking like an adolescent's. "Until I met Angelo, and then Steve moved down to Hudson Avenue. Jesus, if I hadn't met Angelo, maybe Steven would still be here in this place—alive!" His little eyes bugged out.

Angelo said, "Fuck that shit!"

"Angelo, I wasn't accusing you, for chrissakes, now come off it!"

"Daaaaa!"

I said, "Tell me about Steve."

"Oh, he was such a nice boy, rea-l-l-ly nice. Very into music and all. Music was his way of life—like Patti LaBelle, ya know? I just can't believe it that Steven is—that he doesn't even exist anymore. Last week he was here, and this week he's just—gone. I never knew anybody who died before. Except my stepfather, and he was such an asshole." Angelo looked away in disgust.

"Were you and Steve good friends?"

"Oh, yeah, Steven and I were very tight. I mean, we lived together and went out and all. Till I met this ol' grump here. Mister stay-at-home. But Steven and I still kept in touch, gabbed on the phone and all. Steven usually called on Monday and we'd yackety-yack about the weekend. He'd tell me all the dirt that went on and all, who's doing who. God, I can't believe he's never going to call again, I just can't believe it. Gives me the creeps. Iggghhh!" He shivered.

"Who were Steve's other friends?"

"Oh, the jocks, I guess. He hung around mostly with the jocks. Steven was very into music, ya know?"

"I know. What about Billy Blount? Do you have any reason to believe he and Steve had known each other before the night Steve died?"

Loggins looked away. "No. Steven always told me about all his hot tricks. No. He would of said." He glared back at me as if

I were somehow responsible for what had happened to his friend. "Ya know, I don't even know who this Blount asshole is!"

"Right. I've yet to meet Blount myself. What about Steve's love life? Did he ever have a lover?"

Loggins screwed up his face. "Sa-a-yyy—can I ask you something personal?"

"Sure."

"Are you gay?"

Angelo watched me, ready to pounce if I didn't come up with the right answer. Except I wasn't sure what the right answer was. I said, "I wouldn't have been run out of Blooms-bury Square,"

Angelo's lips moved as he repeated this to himself.

Loggins tittered and said, "Well, personally I've never been to San Francisco, but I get your message."

I said, "Who were the men in Steve Kleckner's life that he talked about?"

"How much time have you got, about a day?" He tittered again. "No, I'm just kidding. Really. Steven played around some, like we all do—I mean used to do." He squeezed Angelo's thigh; Angelo smirked lewdly. "Steven never got into anything heavy, though. Not like Angelo and I. He went mostly for one-nighters, ya know? No hassles and all. Except that gets so-o-o tired after a while, right, Angie?" Angelo belched theatrically. Loggins said, "Do you have a lover, Donald?"

"Yes, I do. His name is Timmy."

"Well, I hope he's like Angelo."

"Thank you. What about Mike Truckman? I heard he and Steve were involved at one time."

"Yeah, Steven and Mike were getting it on for a while, right after Steven started working out there. But that was ages ago. Two years ago, it must have been. It didn't work out. Mike was too old for Steven. I kept telling him that. Steven liked to have a good time, dance and go out and all, but Mike's idea of partying was to sit home and get sloshed and then grope around and fall asleep. The pits, Steven said. And Mike was so-o-o jealous. Steven couldn't even look cross-eyed at another guy without Mike having a conniption fit. Steve broke it off finally,

but they stayed tight, even what with Mike boozing it up more and more and starting to fool around with whores. Really sleazy lays, Steven said they were. Even still, Steven really loved Mike, I think. But more like a father. He looked up to him and all. Used to, anyway."

"Used to?"

"Yeah. It was sad. Something bad happened. A bummer."

"What was it?"

"I don't know. Steven wouldn't tell me. Just that it was something incredibly tacky that Mike did. About three weeks ago. It really got Steven down, whatever it was."

"Steve didn't say anything about what it was? Nothing at all?"

"Steven said he'd tell me about it sometime, and I know he would've, but—but—oh, God!—poor Steven!" It had caught up with him. He shuddered once, lowered his head, and began to tremble.

Angelo pulled Loggins against his chest, looked at me, and said, "Fuck this shit!"

I waited until Loggins had recovered and gulped down some of the creme soda Angelo shoved at him. I said, "Just one last thing. What about Steve's family? Was he in touch with them?"

"No—" He snuffled. "They were on the outs." Angelo pulled a Valle's Steak House napkin from his back pocket, and Loggins blew his nose in it. "Steven's folks live over in some hick place in Rensselaer. Last Christmas Steven told his sister he was gay, and she told his mom, and his mom asked him if it was true, and Steven said yes, and you know what Steven's mom said? She started screaming and she says, 'Oh, please, Steven, please don't have an operation! Please don't have an operation!' And then his dad came home and threw him out. He had to thumb back to Albany, and it took him three rides to get back here. He never did figure out what his mom meant by don't get an operation. Sex change, I guess. Who the fuck knows."

Angelo said, "He shouldna told his sister. Bitch! Never tell a woman nothin'!"

"Oh, Angelo, you're such a sexist asshole! Quit being such a fucking pig, would you pu-leez!" "Daaaaa!"

At one I put four Price Chopper frozen waffles in Timmy's toaster oven. He handed me his old Boy Scout hatchet and said he'd pass. I said, "Fuck this shit," and ate an apple. Timmy said he'd do dinner at seven and had to spend the afternoon at the laundromat.

I drove over to Morton. Summer was back, and the air was hazy and sweet. High mackerel clouds swam across the sky over the South Mall, recently renamed the Nelson A. Rockefeller Empire State Plaza in memory of the man who had caused the great granite bureaucratic space station on the Hudson to happen. Back at the apartment the heat, inexplicably, was on. Hurlbut must have forgotten his golf bag and come back. I opened all the windows.

I checked my service—no calls—then dialed the number for Chris. There was no answer. Frank didn't answer either, but I reached Billy Blount's other friend, Huey, and told him I was looking for Billy. He said he doubted he could help but that I could drop by around three. His voice sounded familiar.

I did sit-ups and push-ups, jogged around Lincoln Park for half an hour, then showered, put on jeans and a sweat shirt, and drove back up Delaware. Huey lived on Orange Street, between Central and Clinton, in one of Albany's two mainly black neighborhoods. As I climbed the front-porch stairs of the small frame house with its three or four tiny apartments, I knew I'd been there before.

"I thought I rec-a-nized that sexy voice," he said. "How you been, baby?" A smile spread across his shiny dark face, and his eyes were bright with sly pleasure. He had on a vermilion tank top and cutoff shorts and was barefooted. He'd told me during the night I'd spent with him a year or so back that his tight, neat, muscular body was "the finest in Albany." He'd said it with delighted satisfaction and no trace of embarrassment, and for all I knew, which was a good bit, he might have been right.

In Huey's living room I sat on the old, worn, boxy couch

with little strands of silver running through the black upholstery. I said, "Your voice sounded familiar, too, except I could have sworn the voice belonged to a guy I once knew named Philip Green."

He threw his head back and laughed. "Did I call myself that? Yea-hhh, well. You know how it is, baby."

I knew. "I'd hoped I'd run into you again," I said loudly.

He turned down the volume on Disco 101—M's "Pop Music" was on—and sat on the chair that matched the couch. He smoothed out a fresh white bandage that was wrapped around his exceedingly well developed upper arm and said, "That would have been sweet. We sure had a real good time, as I remember, Ronald."

"Donald."

Laughing, he leaned over and squeezed my ankle. "Can I get chu somethin' to drink? A Coke or a glass of wine or somethin'—Dahn-ald?"

"You can. A Coke."

He went into the kitchenette. There was no evidence that anyone other than Huey was staying in the apartment. I could see into the small, windowless bedroom. The bed was made. The clothes piled atop the old dresser beside it looked like garments Huey could get away with wearing, but not Billy Blount.

"Too bad this ain't a social visit, Donald." He handed me a Coke in a Holiday Inn glass. "Even if you are a cop." He sat down and looked at me.