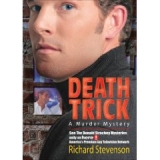

Текст книги "Death Trick "

Автор книги: Richard Stevenson

Жанры:

Слеш

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 13 страниц)

I said, "I'm a private detective," and showed him my license.

"No shit." He examined the card carefully. "How you become one of these dudes? Take a test?" He handed it back.

"You have to have three years' experience as a police, army, or agency investigator, pass an exam, and hock the family jewels to get licensed and bonded."

"Must be in-ter-estin'. You been a cop?" His smile was strained.

"Army intelligence."

"Ooooo, a spy! That sexy."

"That was a while ago. Now I'm on my own and I'm looking for Billy Blount."

"Yeah. You said." He lit a Marlboro. "How come you lookin' round my place, Donald? I don't truck wit no desss-per-ah-does."

"Your name was written on Billy's phone book."

"Yeah. Sergeant Bowman come around, too. Asshole come out here a hell of a lot quicker than the cops who come last night. Took them suckers half an hour to show up after I called, and meanwhile I'm bleedin' like a stuck pig. Some sumbitch busted in here to rip me off, and when I caught him, he cut me. See that?" He raised the bandaged arm. "Eight stitches! Guess I was lucky, though. Coulda been ninety-two. This is what you call your high-crime neighborhood, Donald."

"It was a burglar who cut you?"

"Yeah, I know about the routine. First the dude calls to see if I'm home. This one called twice last night. I answer the phone and there's no one sayin' anything and he hangs up. Checkin' to see if I'm home, which I am, with a friend I run into earlier over at the Terminal. Then around two in the mornin' my friend leaves and I guess this dude's watchin' the house, see, and thinks it's me goin' out, and he comes in that winda there. I was just goin' to sleep and I hear this fucker and I get up and I'm gonna jam his nose right up into his brain, see—I do martial arts, right?—except the guy's got a knife and he cuts me and it's so dark he's back out the winda—head first, I think—before I can kick his balls up his ass. There'd a been lights on, they'd of carried that dude outa here on a stretcher. Anyways, I think he ain't comin' back. Not if he don't want his neck busted off."

"Did you get any kind of look at him?"

"Too dark. Average-size guy, and I'm pretty sure white with light hair. But I doubt I'd rec-a-nize him on the street. Guess I better get the lock fixed on that winda. Been meanin' to for six months."

"Yeah, you should. Look, I might be way off base, but—how do you know this was a burglar?"

A bewildered look. "I don't get chu, Donald."

"Well—it's like this. You know that Steve Kleckner was stabbed in his apartment in the middle of the night just a week ago. The people who know him don't think Billy Blount

committed the murder, and it's possible—do you see what I'm saying?"

He blinked, and I could see the icy tremor run through him. He said, "Nah. Nah, no way. That bad stuff go on all the time around here, Donald. Shee-it. Nah. I don't believe it was the freak who done that murder. This was just some shit-ass dude after my stereo. I didn't even know that Kleckner boy. Had nothin' to do wif his friends or anything."

"But you know Billy Blount. The, uh, intruder—he didn't look like Billy, did he?"

He gave me a cold, hard look and said, "No. Billy I'd know. I know Billy."

"Sure. You would. And you're right; there's probably no connection. But you'll get that lock fixed, right?"

"Sure, Donald. If it'll put your mind at ease." He grinned. "Wouldn't want chu to worry about ol' Huey unless you was gonna be here to worry 'bout me in person and we could cheer us bofe up. Ain't that right, baby?"

"Just get the lock fixed," I said, ambivalence swelling like a doughy lump in my lower abdomen. "Knowing that you're safe will cheer me up enough for now."

He chuckled.

I said, "Fill me in on Sergeant Bowman's visit. What did you tell him?"

His eyes narrowed, and I could see the perspiration forming on his forehead. "I told him, 'Yassuh, no suh, yassuh, no suh.'" He laughed quietly. "Motherfucker called me some nasty names." He dragged deeply on his cigarette.

I said, "I'll meet Bowman on Monday. He sounds like a treat. I take it Billy hasn't been in touch."

"Unh-unh. I wisht he did. I could help him out."

"How?"

"Hide him out wif some friends of mine."

I said, "It's obvious you're among the many who don't think Billy did it—killed Steve Kleckner."

He contained his impatience with my belaboring what was plainly absurd to him. "No. Not do a thing like that. Not Billy. Now, what else do you want to know, Donald. Just don't ask me no more questions that might make me mad. Okay, baby?"

"Then tell me what you know about Billy. If he didn't do it,

I want to help get him out of this. But I'm going to have to find him first."

Huey slouched in his chair and fingered the bandage on his arm. "Billy's a sweet man, that's what. One of the sweetest men I've had the pleasure to meet around Albany. Present company excepted." He leered pleasantly. "We've had some very enjoyable times together, Billy and me."

"Did you go out together much?"

"Sometimes we'd go dancin'. At the Bung Cellar, or Trucky's if we could get a ride. Mostly we'd just hang around his place, or he'd come over here. Just listenin' to music, and smokin', and lovin'—that's what we bofe liked mostly. A sweet, nice man."

"When did you last see Billy?"

"'Bout a week before the thing happened. Spent the night right there on that couch you're sittin' on. He gets up Sunday mornin', says so long, and that's the last I seen him. I was about to call him when I seen on TV what'd happened."

Billy Blount the sofa fetishist. "Is this a hide-a-bed?"

"Yeah, folds out. Billy couldn't stand my bedroom. No windows. Freaked him out. Made him all antsy. I figgered maybe he'd done time wunst, but when I axed him he said unh-unh. Wouldn't of figgered, anyways. Billy went to college. I done ten months at Albany County Jail myself—told Billy about it and it made him mopey. Made me mopey, too, baby! I was seventeen. Breakin' and enterin'. And I'll tell you, Donald, I ain't gone back in. Them places fulla booty bandits! Me, I like to pick and choose. I'da choosed Billy any day. A sweet man, Billy."

I asked him where he and Billy had met.

He chuckled. "Where did you and me meet, my man?"

The great outdoors. "Who are his other friends in Albany? Anybody he might go to or get in touch with?"

He looked a little hurt with the idea Blount might have closer, more relied-upon friends. He shrugged. "Maybe some guy name-uh Mark who rode us out to Trucky's coupla times. White dude wif whiskers. And Frank somebody. I never seen that one—I think Billy mostly just bought dope from him. Got some for me wunst when my dealer was busted.

"And then there was this chick, I think, too. We run into

this chick up at McDonald's on Central one night, and Billy goes out to the parkin' lot for about an hour, it seemed like. I seen 'em outside in her little V-dubya buggy. I got pissed and tired of waitin' and went out and stood, and then Billy come along. Says she's the finest woman he knows and if things was different he'd marry her. How about that, huh?"

"What was her name? Do you remember?"

"He didn't say. Just called her his lifeboat, or lifesaver, or somethin'. Billy's a trip. I'da never figgered he went for women, but you never know. I've even been known to indulge myself every now and again, though naturally I try to keep it under control. How about yourself, Donald?" He grinned.

I said, "These days, half the human race is enough for me. Though, I have a lover now."

"Ahh, that's nice, Donald. Truly. I had a lover wunst. Melvin. He was my true, true love. We was together for five bee-yoo-tee-ful years. Lotta good times—till the Lord called Melvin away."

"Oh, no. He died?"

"Shee-it, no. Become a preacher. Took Jesus as his lover. And I just couldn't compete with that man, baby! Melvin's out in Buffalo now savin' black folks' souls. Oh, he still pays me a visit from tahm-tew-tahm. Just on very special o-kay-zham." He laughed and shook his head at something that went beyond Melvin.

I said, "What about Chris? Did Billy ever mention a guy named Chris?"

Huey lit another Marlboro. "No. That one don't ring a bell. Who's Chris?"

"I don't know yet. The name was written on Billy's phone book. How about Eddie? This would be someone Billy knew once that he'd be happy about running into again."

He shook his head. "No. No Eddie I can think of. Don't know who that would be. Billy had folks, of course. That's who you workin' for, right?"

"Yes."

"They wasn't close. It's good they helpin' the boy now he needs a helpin' hand. I'm glad."

"Did Billy ever talk about them?"

"Nothin' much. 'Cept they carried on like the wrath o' the Lord about him bein' a ho-mo-sex-ual."

"We all have parents. Mine don't know. They've let it be known they'd rather not."

He dragged on his cigarette and blew the smoke out slowly. "My folks don't much mind—or don't let on, anyways. I got a gay uncle who's a big shot at Grace Baptist down home in Philly. My brothers is straight. They don't hassle me. I been lucky, I guess." He looked at me and smiled. "Say, get chu another Coke? Some wine? A smoke?"

It would have been nice to linger with Huey—for about forty-eight hours. Disco 101 was playing Earth, Wind and Fire's "The Way of the World."

I said, "No. Thanks. I'm working. Another time."

He said, "Mmm-hmmm. Another time. You got it, baby."

I gave him my business card. "Call me if you hear anything, right? And get that lock fixed."

"You're on. You find Billy and bring him back, hear? You want to get in touch, I'm at Burgess Machine Shop—I'm a welder—and nights you'll find me out and around."

I got up to leave.

"Huey, one more question. Tell me if it's too personal. Ready? Here it comes. What's your last name?"

His face lit up, and he came over and hugged me. "Brownlee. Hubert Brownlee. Think you can remember it?"

I said, "Until I get to the car. Then I'll write it down."

We kissed for a minute or two, and then I maneuvered my way down the stairs like a drunk, made it to the Rabbit, got out my pad, and wrote: "Huey Redmond." But it didn't look right.

5

I REACHED FRANK ZIMKA FROM A PAY PHONE ON CENTRAL. I

explained who I was and what I wanted, and he said, "I can't talk to you," and hung up.

I tried Chris again. No answer.

Frank Zimka's address was in the phone book, so I drove over to his place on Lexington.

Zimka's name was taped to the mailbox of the basement apartment in an old brown shingled building. To get to it you had to crouch down and lower yourself into a concrete well under the wooden front steps. I knocked on the door glass, which rattled in its frame. The chipped porcelain doorknob hung from a string coming out of the spindle hole.

The door was slightly cockeyed—or the building around it was—and when Zimka opened it, it scraped across the threshold in jerks.

"Yes?"

His young body was slim and well proportioned in wrinkled khakis and a once-white T-shirt, and he looked at me suspiciously out of a haggard, peculiarly aged face. His eyes and curly hair were of an indeterminate color, as if something had caused the hue to weaken and fade out. The bone structure of his face was that of a classically handsome young man, but the lines of age were already set, and there was a shadowy tightness around his eyes. He looked like the result of some crazy secret Russian experiment in which a forty-five-year-old head had been grafted to the body of a man twenty years younger.

I said, "I'm Donald Strachey. If you're a true friend of Billy Blount, you'll want to talk to me. I don't believe he's guilty, and I'm going to help him get out of this." It was the first time I'd said this out loud, and when I said it, it sounded right.

Zimka gave me a blinking, blank-eyed look, as if I'd interrupted a restless sleep. "Billy's out of town. I don't know where he is." He started to scrape the door shut, then thought of something. "Billy's not in jail, is he?"

"He hasn't been found. I hope to find him soon. Can I come in?"

He blinked some more and gazed down at the leaves and debris at our feet. Finally he said, "I'm crashing, but suit yourself."

He turned and went inside, and I followed, dragging the door shut behind us. Mark Deslonde had told me that Zimka dealt dope but not that he used it. Though it figured. I'd get what I could.

We entered a low-ceilinged living room with a gas space heater on a dirty linoleum floor, an old green couch, a discount-store molded-plastic chair with chrome legs, and a lamp with a shiny ceramic panther base on an end table. A tin ashtray was full of white filtered butts. I could see a small kitchen through a doorway, and the place stank mildly of garbage. Through another doorway I could make out an unmade double bed under a dim red light bulb.

Zimka sat on the plastic chair and lit a Kent with a butane lighter. I sat on the couch. I said, "You mentioned that Billy's out of town. How do you know? Has he been in touch?"

He dragged deeply on the cigarette, as if it might contain nourishment. His dazed look came back. "Who did you say you were? Tell me again."

I got out the card. "I'm a private detective, and Billy's parents have hired me to find him. I'm not a cop, and don't judge me by what you might think of the Blounts. I've met some of Billy's friends, and I think I share their opinion that he's innocent. Do you?"

He brought his heel up to the edge of the seat and hugged his leg. He lay his cheek against his knee and said quietly, "I wouldn't care what Billy did."

"I can see that you're very fond of him."

He tensed. "Maybe I am. You really would not understand."

"Would it help if I told you that I'm gay, too?"

"A gay—detective?"

He looked at me as if I'd told him I were a homosexual table lamp.

"I'm sure there are others. I've met two. Generally they don't announce it. It's been changing a little, but law enforcement is not one of the nation's bastions of enlightened social thought."

"That's funny," he said mirthlessly. "A fag real detective. I knew some of the TV detectives were gay." He mentioned a famous television sleuth who had once passed through Albany and caused a sensation at the Bung Cellar when it was still Mary-Mary's. "But he's just an actor," Zimka said glumly, "not a real detective. Actually, I probably should have done that

myself. Been an actor. I'm a pretty good one—Billy could tell you about that." A hurt, bitter look.

"It sounds like a complicated relationship you have with Billy. Complicated and very close."

He sat motionless for a long time, blinking and breathing heavily. Then, his voice breaking, just barely audible, he said: "I love him."

He pressed his forehead hard against his knee and shut his eyes tightly. The hand with the cigarette was up next to his ear, and I watched it, afraid his hair might catch fire. The smoke curled up through a shaft of dusty sunlight coming in through a window with plastic sheeting over it.

I said, "Are you and Billy lovers?"

He looked up at me with wet, angry eyes. "That's not what I said. I said I love him."

"Right. I get your meaning. That's hard."

He said, "Yes. It is." He got up and stubbed out the cigarette in the dish full of butts. "You want a white? I could use one."

"How about a beer? It's hot again."

He went to the kitchen and came back with a Schlitz for me, a glass of water and a white pill for himself. A church key was on the end table, and he opened the bottle.

"This is a treat," I said.

He sat on the plastic chair, popped the white, and washed it down. Then he lit another cigarette.

"You know where he is," I said. "Don't you?"

He closed his eyes and shook his head. "No. I don't know where Billy is. I wish I did. Maybe I'd go there. Though I guess I wouldn't."

"But you know he's not in Albany."

"Billy's somewhere a long way from here. I know that. I lent him the money."

"The morning it happened?"

"Early in the morning. He came over here." He gave me a hard, questioning look. "You know, I don't even know you, do I? How do I know I can trust you?"

"You don't know. It's a risk you're taking. You strike me as someone who takes risks."

He laughed sourly. "Yeah. I do. Look—if—if I tell you what I know—will you give Billy something from me when you find him?"

"Sure."

"You promise?"

"I promise."

"And you won't tell the police?"

"I will not."

He sighed. "Okay," he said, working up to it, shifting, putting his feet on the floor. "Okay." He sucked on the cigarette. "This is what happened. As far as I know, this is what happened. I don't know all of what happened, right?"

He waited.

"Right," I said. "Just what you know."

"Okay. Okay, then. Well—around six that morning Billy came and banged on my door. I almost didn't wake up—I'd had a busy night." He gave me a look, and I acknowledged it. "Anyway, I let him in, and I could tell he was nervous and scared. He said—he said somebody had stabbed the guy he went home with—some new guy he met out at Trucky's—and the guy was dead. That he'd felt his pulse and he was sure the guy was dead."

"Billy saw the stabbing?"

"No. He didn't say that. But I guess he didn't see it, because he didn't know who had done it."

"A threesome. Maybe they'd picked up a third guy on the way to Kleckner's place."

"Billy didn't mention that. I don't think he would've, anyway. Billy's pretty straight in a lot of ways."

"How could he not see it happen if he was there?"

"Well, he must've—I don't know. Maybe he'd gone out."

"At five in the morning? And then come back?"

"You don't believe me."

"I believe you. What else did he say? Try to remember his words."

"He just said, 'Steve is dead, the poor guy is dead, and they're going to think I did it.' He said, 'They're going to try to lock me up.' He said that about a hundred times, I think. 'Shit, they're gonna lock me up and throw away the key! They're

gonna zap me good!' Billy was really freaking out, and by that time I was starting to feel pretty freaky, too."

"Had Billy been locked up before?"

"I think so. I don't know. He would never talk about it. Whatever it was."

"So he came here and said these things. What happened then?"

"He wanted me to lend him money."

"What for?"

"Well, for plane fare, what else?" A sharp, hyped-up tone now—the dexie had reached his bloodstream.

"Did you lend it?"

"Of course."

"How much?"

"All I had. Almost two-forty."

'Two hundred forty dollars? You keep a good bit of cash around."

"I deal. Grass, some hash, pills. And I hustle." He waited for me to react; I didn't.

"Where was Billy planning on flying to?"

"He wouldn't tell me. He said he had friends who he knew would help him, but they wouldn't want anybody to know where they were."

"What else did he say about them? These friends."

"That's all."

"What happened next?"

"I drove Billy to New York. He asked me to."

"New York City?"

"La Guardia. He was afraid he might see somebody he knew at the Albany airport. We stopped over at his place first and he brought a suitcase."

"What kind of car do you have? Describe it." I thought I believed him, but any kind of verification of his story wasn't going to hurt.

"I don't have a car. A guy I know lets me use his sometimes."

"At that time of day?"

"If I ask, this guy helps me out. He likes me. Do you?"

"Sure. I like you. Who's the owner of the car?"

Zimka rolled his big, drugged eyes. "You've heard of him. But I'm sure he'd prefer I didn't mention his name." He giggled.

"So you picked up the car."

"I called my friend first and then I walked over and got the car—this guy's place is right over by the park on Willett—and then we picked up Billy's suitcase and drove out to the Thruway."

"What did you talk about during the ride down?"

"Us. We talked about us."

"You and Billy."

"Yeah. Me and Billy. I told him how I felt about him. For the first time I told him how much he meant to me."

"Was he surprised?"

"Shit, no. He knew. Nobody could experience what I've experienced with Billy and the other person not know. There's sex, and then there is—mak-ing lov-v-v-ve." He impersonated Marlene Dietrich.

"In my experience it's not always that clear-cut," I said. "Are you saying that in bed you were making love and Billy was just getting it off?"

He grinned inanely. "I'm not going to tell you about that. It's humiliating. It's none of your business. When are you leaving?"

"Soon. How long have you known Billy, Frank?"

"Three years. Three years next month. November fourteenth." His cigarette had burned itself out; an inch of ash fell onto his pant leg and lay there. "I met him over at the Terminal one night," Zimka said. "He cruised me. And I really thought that night that he liked me. That he liked me."

"But he really-didn't?"

"It's too complicated. I'm not going to talk about this anymore. Not to you. You're about to leave. It's too bad it'll never work with Billy and me. Really too bad. He's been great for me. Billy opened up a lot of positive things inside me I never knew were there. It's too bad. I can be a really fabulous person. Are you leaving now?"

"I'm sure you can be. I'll leave soon. What happened in New York?"

"New York?"

"At the airport. La Guardia."

"I dropped him off."

"What time?"

"Nine. Or nine-fifteen."

"You didn't go in with him?"

"He wouldn't let me. He said he'd send me the money, he thanked me, he gave me a little brotherly kiss. And then he– took off!" He imitated an airplane.

"You drove back to Albany then?"

"No."

"No?"

"Fucking Billy took every cent I had! I had no money for gas or tolls coming back." He giggled. "So what I did was, I stopped in Scarsdale and called a guy I knew. Scared the royal blue shit out of him, too. He met me at a gas station and says, 'Nice to see you, Frank,' tosses me fifty, and took off in his BMW like I'm diseased. He's one of my admirers. He likes me."

Every life tells a story. "How old are you, Frank?"

"How old do you think?"

"Twenty-four."

"Twenty-six. My face looks fifty."

"I would have said thirty, or thirty-five. Still, maybe you should be looking into a somewhat more restful line of work."

"I'm a chemist," he said. "I graduated RPI cum laude."

"Why don't you work as a chemist, then? Or at something else in the sciences, or whatever, that you might be good at? Why not try it—maybe just something part-time to start out?"

His eyes were like baby spotlights now. He said, "I think I'll get a job as the president of MIT!" He laughed idiotically.

I drank my beer. I asked Zimka whether he'd had any odd phone calls recently in which the caller didn't speak but just listened, or whether anyone had tried within the past week to break into his apartment. He looked at me as if I'd asked him if his hair were on fire, then giggled. I asked him if he knew who Chris was, and he summoned up the clarity of mind to say no. I asked him if he knew who Eddie was, and this caused another fit of uncontrolled hilarity. Finally I asked Zimka if the police had been in touch—his number was written on Billy Blount's

phone book. He said yes, but he'd told them he was the Queen of the Netherlands and they hadn't returned.

I thanked him, gave him my card, and asked him to get in touch with me if he heard from Billy Blount or if the money Billy had borrowed was returned in any manner. He asked me to stop by on Monday to pick up something he said he'd have for Billy, and I said I would.

I shook his hand and left. He may or may not have noticed my going.

6

AT TIMMY'S I CHECKED MY SERVICE WHILE HE MADE MASHED

potatoes to go with the roast chicken. He used a real masher, and I admired his domestic skills. At my place I boiled the potatoes, put them in a Price Chopper freezer bag, and beat them with a hammer wrapped in a towel.

There were two messages, one from a former client who owed me three hundred dollars. He said, "The check is in the mail." The other message was from Brigit: "Books will be found on front lawn after noon Sunday."

I asked, "What's the weather forecast?"

"Showers or drizzle later tonight," Timmy said. "It's supposed to clear late tomorrow and get cold again."

"Crap."

Brigit's new husband and his four daughters were moving into our old place in Latham, and they needed the room where I had my books stored. The Rabbit wasn't going to do the job, and Timmy drove a little Chevy Vega.

I said, "Brigit means business about the books. We'll either have to make six trips or rent a U-haul."

"We?"

"Would you help me move the books, please?"

"Yes."

"She says noon tomorrow, then she chucks them out. She's a sweetheart."

"Right, you've been so busy for the past month." He dropped a brick of frozen peas into a saucepan.

I said, "The heart has its reasons."

"For not picking up a load of books?"

"Don't confuse the issue. Brigit hasn't been nice."

"It's a diabolical retribution—books."

"One does what one can."

"It's the final break. That's why you've been putting it off. This is really the end and you won't face it." He took the chicken out of the oven and set it on the trivet on the table.

"Not true. The final break was three years ago. In a courtroom with portraits of two Livingstons, a Clinton, and a Fish." I began hacking away at the chicken with a bread knife. Timmy winced.

"Why don't you let me do that? You carve the mashed potatoes." I went looking for a serving spoon. "The final final break," Timmy said, "will come when Brigit smiles warmly and shakes your hand and says, 'Heck, Don, at least we had seven wonderful years. I understand and sympathize and there'll be no hard feelings on my part.' That's the final break you're waiting for, except it's not going to happen."

"I can't find a spoon."

"Middle drawer."

"How come I keep getting mixed up with people who devote their lives to explaining me to me? Brigit did that. It's a powerful force to constantly contend with."

"Nature abhors a vacuum."

"Like the poet said, fuck you. Anyway, I make my way in the world. I understand enough of what's going on. I do all right."

"That you do."

"You don't make it easier."

"Of course I do."

I said, "You're right. You do. Let's eat." * * *

Over dinner I told Timmy about my two visits with Billy Blount's friends and what I'd found out about Blount. "It turns out he's not so morbidly attached to the duke and duchess as I thought he was. That's just how they see it—or want others to see it. In fact, he seems reasonably stable and in control of his life. And sufficiently resourceful that he knew just where to go when trouble happened. He went somewhere you can fly to for two hundred forty bucks."

That could be just about anywhere these days. You can get to London for under a hundred and fifty."

"Not from La Guardia. That'd be JFK. I've got to find somebody who can check passenger manifests. Deslonde says Blount once had friends on the West Coast. He could be out there."

"Maybe he flew under another name. It's easy."

"Could be. He was thinking."

The cops could check. Are you going to tell them?"

"Later. In due course. Are there more rolls?"

"In the oven."

The people who know Blount best speak well of him. Everybody says he's likable and fun to be around, though a bit verbose and dogmatic. But he's got no real hangups that get to people, and certainly no violent streak. He does have some private grief he keeps inside—an irrational, or possibly entirely rational, fear of being shut in or locked up. Something that happened to him once. Huey and Mark and Frank Zimka all mentioned it. I'll have to check that out with the Blounts. It would explain his panic to get away, even if he hadn't committed the murder."

"Or even if he had."

"Yeah. There's that."

"He didn't tell Zimka anything about how it happened?"

"Not much. Either that, or Zimka is holding something back–or even making the whole story up. This is possible; Zimka's brain couldn't have survived its owner's life unscathed. Zimka may lie as naturally as he blinks. Anyway, for what it's worth, Blount was there, Zimka said, but he didn't actually see the stabbing or the person who did it."

"He was in the bathroom. Had to piss."

"How long does that take?"

"Or brush his teeth."

"When you used to trick, did you carry a toothbrush?"

"That was too long ago. I don't remember. How about you?" He looked up at me from his plate and then down again.

"And another thing is, I can't figure out Blount's connection with Zimka. His other friends, so far, are nice wholesome folks. Like Deslonde, for instance."

"Right," Timmy said. "Like Mark."

"I liked Huey and Mark and saw what Blount saw in them. Zimka, on the other hand, is badly screwed up—not entirely lacking in the decenter instincts, but he's a slave to some unholy habits, and when he's down off his pills, his outlook on human life is decidedly gloomy. Why did Blount hang around a guy like that? There's a side to Billy Blount I don't understand yet."

"Money. You said the guy had ready cash. Blount used him."

"For what? Blount had no expensive habits. None that I know of." I looked at my empty plate.

"Coffee?"

"Yeah, I guess. And the knife attack on Huey what's-his-name last night. It probably doesn't have anything to do with Blount or the Kleckner killing, but still—have you ever heard of a white burglar operating in Arbor Hill?"

"That might be a first."

"Mm. It might."

"So. What's next?"

"There's a guy by the name of Chris I have to check out. And there's a woman Blount evidently was close to. Huey saw them together once."

"Ahh, a mystery woman. In an evening gown and black cape? Maybe it was Megan Marshak."

"In a VW bug. That's all I know about her. This one might slip through my ordinarily ubiquitous dragnet."

"Oh, I doubt that. You know, you're going to an awful lot of trouble to find Billy Blount, when the fact is, everybody who

knows him well is convinced he's not a killer. If Blount didn't do it, shouldn't you be giving some thought to who did?"

"I'm doing that."

"Ideas?"

"None worth mentioning. Not yet."

Timmy got up and started clearing the table. "What are we doing tonight? Working or playing?"

"Let's make the regular stops and see what turns up."

When we left the Terminal at nine forty-five, a light rain was falling. I went back in and called U-Haul on the pay phone and reserved a van for eleven-thirty the next morning. Then I called Brigit and told her to expect us around eleven fifty-nine.