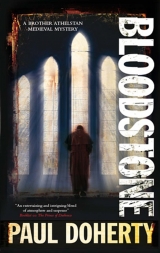

Текст книги "Bloodstone"

Автор книги: Paul Doherty

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 6 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

‘Do you see Richer as your enemy?’

‘No, Brother, but he may view us as his.’

‘So why are you armed?’

‘Because,’ Wenlock intervened, ‘three weeks ago, just before the beginning of Advent, I was attacked out in the abbey grounds. I have a passion for herbs and shrubs – I always have. I visited the gardens and afterwards I went for a walk. Nearby runs a maze, its high hedgerows, all prickly, laid out in a subtle plan. A former abbot had built it so those who could not take the cross to Outremer to fight the infidel could crawl through its maze of narrow paths to the centre where there is a Great Pity surmounted by a cross. I entered but dusk was creeping in. I was about to leave when a figure charged out of the gloom, hooded and masked, sword and dagger whirling. I was petrified; all I carried was a pilgrim staff.’ Wenlock grimaced. ‘The forefingers of both my hands are maimed, the French, God curse them. I cannot pull a bow but still, albeit clumsily, wield a weapon.’

‘You fought your assailant off?’

‘I was out looking for Wenlock,’ Mahant spoke up. ‘I heard the shouting, the slash and clatter. I answered Wenlock’s cries of ‘ Aux aide! Aux aide!’ By the time I arrived his assailant had fled; from that time on we decided to go armed.’

‘And you reported all this to Father Abbot?’

‘I might as well have talked to his stupid swan!’

‘And you have no idea of your attacker?’

‘No, he was dressed all in black, cowled and masked.’

‘Or why you were attacked, at that time, in that place?’

‘None whatsoever.’

‘Have any of you,’ Athelstan persisted, ‘relatives outside this abbey?’

‘Not that we know of, we are old soldiers. Some of us were married but now our wives are dead.’ Mahant’s voice turned wistful. ‘Whatever children we had lie cold beside them.’

‘As do two of your comrades?’

‘Brother, Sir John?’ Wenlock’s voice turned pleading. ‘We are finished, surely?’

‘I would like to inspect the chambers of the dead men.’ Cranston rose swiftly to his feet. ‘And that includes William Chalk’s.’ Cranston gestured towards the door. ‘Now, sirs. With you or without you. .?’

The anchorite, whom the old soldiers described as mad as a March hare, stared calmly through the aperture of his anker house on the south aisle of the abbey church. The monks had finished their hour of divine office. They’d left in a soft slither of sandal and the bobbing light of lantern horns. A cold breeze now seeped through an opened door to whip the remaining glow of candles and tapers. Gusts of sweet beeswax and incense still trailed. Here and there the silence was disturbed by the scurrying of mice and rats sheltering in this forest of stone against the savage cold outside. The anchorite wondered what he might see tonight. He’d heard of Hyde pricked to death near the watergate. The anchorite had tried to warn him. He’d seen Hyde leaving in pursuit of some monk – was it the Frenchman Richer? Then another shadow followed him – a monk, surely? The anchorite was certain of that. He’d seen the flitting blackness through the dark. He glimpsed the glint of steel, but that was life, was it not? Violent and turbulent, full of tension and strife, that’s why he sheltered in these sacred precincts with his precious manuscripts, his box of treasure and pallet of paints. He was an anchorite but an exceptional one. He performed one service for the Lord Abbot which few painters did. The abbot was a Grand Seigneur with all the powers of a lord, of Oyer and Terminer, of being Justice of Assize. He had the power of axe, tumbril and gallows and the anchorite served as the abbot’s hangman. In return Lord Walter had been good, allowing the anchorite, when the church was deserted, to leave his cell and paint visions of the life hereafter on the walls and pillars around his cell. Yet she, Alice Rednal, the sinister haunter of his life, had followed him here. The anchorite was sure of that. He’d seen Alice Rednal’s hard face pressed up against the aperture, features all ghoulish, hair as tangled as a briar bush, but that couldn’t be, surely? He’d hanged Rednal at the Elms in Smithfield. He had tolerated her taunting as they rattled along in the execution cart but he’d then watched her die. The anchorite moved back to his small carrel and chancery stool. He sat, picked up his quill pen, opened his journal and began to describe the nightmare which always plagued his sleep. Was this, he wondered, the cause of the recent horrid apparitions?

‘Suddenly, without warning,’ he whispered as he wrote, ‘I saw the witch, yes I did,’ the anchorite glanced towards his cot bed, ‘climbing on to me. It greatly shocked me. I was so terrified I could not speak. In one hand the harridan carried a wooden coffin and in the other a sharpened scythe. She put a foot upon my chest to restrain me.’ The anchorite pushed his journal aside and crept back towards the aperture. He peered through at the painting on the far pillar, the evocation of his own nightmare which haunted him day and night, awake or asleep. He had executed that. At the time he’d been proud of it, and so had the good brothers who’d called it a vivid ‘ Memento Mori’. Now the anchorite was not so sure as he gazed out in the juddering light of a torch fixed in an iron sconce above the painting. He had depicted Death as that night-hag, her face gnawed away to gleaming white bone. He’d intended to paint black hollow eye sockets but instead he had given her red glaring eyes, her teeth jutting up loose in a large jaw, arms stretched out like scaly bat wings. The anchorite turned away then froze at the rustling of a robe and the slither of soft buskins. He hurried back to the anker slit. He was sure she was there – Alice Rednal had returned to haunt him. The anchorite wanted to scream but he could not, he dare not.

‘Go back to hell!’ he whispered hoarsely. ‘Go back I sent you there! Go back! In the name of the Lord and all that is holy I adjure you to return and stay there.’ He grasped the stoup of holy water which stood just within the doorway and feverishly threw a few drops about, but the cold pricking of his spine and the nape of his neck only deepened. She had come. The anchorite closed his eyes trying to summon up images of the Virgin and Child but he could not. All he could picture was a chamber full of flames and filth where venomous demons danced.

‘Hangman of Rochester, I promised you would see me again. Alice is here.’ The woman’s voice sounded like the hissing of a curling viper.

‘What do you want?’ the anchorite pleaded. ‘In God’s name, what do you want?’

‘Your soul!’

‘That is the Lord’s.’

‘Then your blood money.’

The anchorite glanced at the small silver-hooped casket crammed with precious coins.

‘Never!’ He turned, looked and recoiled at the face leering through the aperture, chalky white with glaring eyes.

‘Remember me?’ the voice hissed. ‘At the hanging tomorrow I will see you there, perhaps?’

The anchorite grabbed the pole he kept near his bed and turned to thrust it through the gap, but the phantasm had disappeared. The anchorite closed his eyes and fell to his knees, sobbing in prayer. .

THREE

‘Forsteal: a violent affray.’

‘The day of their destruction draws near,

Doom comes on wings towards them. .’

The melodious chant of the black monks of St Fulcher rose and fell in the taper-lit darkness of their great oak-carved choir close to the high altar. Athelstan leaned against the raised stall and tried not to be distracted by the images clustering around him. The sculptures, the vivid wall paintings, the shimmering colour of stained-glass windows, the darkness brooding at the edge of flickering light, not to mention row upon row of black garbed monks, their faces hidden by cowls – all of these were a constant temptation to gaze around.

‘I have sharpened my flashing sword,’ the choir sang.

Athelstan smiled at the words of the psalmist. Coroner Cranston had decided to curb his sharpened thirst in the refectory of the guest house, though not before telling Athelstan that they would not be returning to the city that evening. Athelstan had reluctantly agreed. He wanted to return to St Erconwald’s. God knows he had enough work there but the business here was compelling. This great abbey absorbed him. In itself it was a small stone city. At its centre stood this hallowed cathedral with its transepts and arches, pillars and plinths, its great rood screen carved in the same fine oak as the latticed woodwork of the chantry chapels dedicated to this saint or that which ranged along each aisle. Athelstan would love to bring his parishioners around this church, show them the exciting wall paintings and frescoes, the great table tombs of former abbots, the elaborate pulpit surmounted by a gorgeous banner displaying the Five Wounds of Christ. Perhaps the swan-loving abbot would grant such permission? A Christmas treat with a feast of bread and ale in the abbey buttery? But not now!

Athelstan let his mind drift. He had visited the narrow chambers of all three dead men. A sad experience. He and Cranston had gone through a collection of paltry possessions: badges, scraps of letters, weapons, clothing and pieces of armour, be it a wrist brace or an ugly-looking dagger. Nothing remarkable except in William Chalk’s, those pieces of parchment bearing the crudely inscribed words, ‘ Jesu Miserere– Jesus have mercy on me’, repeated time and again. Athelstan had asked Wenlock the reason for this. He simply pulled a face and said that Chalk, like any man, was fearful of approaching death. For the rest. .

Athelstan stared up at a statue of St Fulcher. Those bare, whitewashed chambers with their pathetic possessions intrigued him. Something was wrong, Athelstan reflected. Ah, that was it! He smiled. Yes, they were far too neat and tidy, as if someone had already searched the dead men’s possessions – to remove what? Any suspicion about their past, the Passio Christi or some other bloody deed they’d perpetrated during the long years of war. .?

‘Then would the waters have engulfed us.’

Before the leading cantor’s words could be answered by the choir, a voice low but carrying echoed through the church.

‘And they have engulfed me,’ the voice continued. ‘Yea, I am caught in the fowler’s net and the trap has been sprung.’ The voice faded.

‘The anchorite, God bless him,’ the monk next to Athelstan whispered. ‘He has to hang a man tomorrow.’

The cantor, now recovered from his surprise, repeated the verse and the plain chant continued. Athelstan peered down the church and quietly promised himself a visit to the anchorite sooner rather than later. At the end of compline Athelstan expected Father Abbot, seated in his elaborately carved stall, to rise garbed in all his pontificals and deliver the final blessing. Instead a strange ceremony ensued, the likes of which Athelstan had never seen before. The monks sat down in their stalls, cowled heads bowed. A side door in the nave opened. Four burly lay brothers, armed with iron-tipped staves, brought in a man dressed in a black tunic, feet bare, hands bound, his face hidden by a mask. Immediately the cantor rose and began singing the seven penitential psalms as the prisoner was forced to kneel between black cloths set over trestles. Athelstan had noticed these when he had first come under the rood screen into the choir. As the monks chanted, Prior Alexander left his stall and thrust a crucifix into the prisoner’s bound hands. Other brothers wheeled a coffin just inside the rood screen whilst the almoner brought a tray carrying a flagon of wine and a platter of bread, cheese and salted bacon. Athelstan recalled the coffin he had seen and the gallows near the watergate. The abbot must have seigneural jurisdiction. The prisoner now before them was undoubtedly condemned to hang on the morrow though not before his soul was shriven and his belly filled with food. Athelstan whispered a question to the monk in the next stall. The good brother broke off from chanting the ‘ De Profundis’ – and swiftly answered, before the prior coughed dramatically in their direction, how the prisoner was a convicted river pirate who’d murdered one of their lay brothers. The felon had fled to a church further up the Thames to claim sanctuary but eventually surrendered himself to the abbot’s court. He had been tried and condemned to hang from the gallows after the Jesus Mass the following day.

The penitential service finished. The good brothers filed out of their stalls, past the prisoner who now sat in his coffin, ringed by guards. Athelstan followed the others and, once out of the abbey church, he joined the rest in washing his hands and face in the spacious lavarium near the great cloisters. Afterwards, led by a servitor, Athelstan joined Cranston for supper in the abbot’s own dining chamber, a magnificent wood-panelled room warmed by a roaring fire. Thick turkey rugs covered the floor and skilfully painted cloths hung over the square, mullioned-glass windows. The splendid dining table had been covered in samite and a huge golden Nef or salt seller, carved in the shape of a war cog in full sail, stood at its centre. The platters, tranchers and goblets were of pure silver and gold. Napkins of the finest linen draped beautifully fluted Venetian glasses to hold water drawn from the abbey’s own spring. The wines, both red and white were, so Abbot Walter assured them, from the richest vineyards outside Bordeaux. Athelstan wasn’t hungry but the mouth-watering odours from the abbot’s kitchens pricked his appetite whilst Cranston, now bereft of cloak and beaver hat, sat enthroned like a prince rubbing his hands in relish. Other guests joined them: Prior Alexander, Richer and the ladies Athelstan had glimpsed earlier. The young, fresh-faced woman was Isabella Velours, the abbot’s niece; the older one Eleanor Remiet, the abbot’s widowed sister. Isabella was dressed for the occasion in a tight fitting gown of green samite, a gold cord around her slender waist, her fair hair hidden beneath a pure white veil of the finest gauze. Mistress Eleanor, however, was garbed like a nun though in a costly dark blue dress tied tightly just under her chin, a veil of the same colour covering her hair and a stiff white wimple framing her harsh, imperious face. Unlike Isabella she wore no rings, brooches, collars or necklaces. Both women bowed to Cranston and Athelstan, then as soon as Abbot Walter delivered the ‘ Benedicite’ they sat down on the high-backed chairs, grasped their water glasses and whispered busily between themselves. Occasionally Athelstan caught Isabella throwing coy glances at Richer, who always tactfully smiled back. The door to the kitchen opened in a billow of sweet fragrances. Leda the swan, wings half extended, waddled up to the top of the table to receive some delicacies from the abbot. Prior Alexander audibly groaned and loudly muttered that perhaps the swan could be served up in another way. The cutting remark was not lost on Abbot Walter, who grimaced and seemed about to reply in kind but then the first course was promptly served: dates stuffed with egg and cheese, spiced chestnuts, cabbage and almond soup, lentils and lamb, strips of beef roasted in a thick sauce and slices of stuffed pike. Servitors refilled wine goblets and water glasses. For a while the conversation was general: the state of the roads, French piracy in the Narrow Seas, the demand from the Crown for a poll tax and the growing unrest in the city and surrounding shires. The conversation turned to the emergence of the Great Community of the Realm, that shadowy, fervent movement amongst the shire peasants and city poor, threatening revolution and preaching the brotherhood of man. The name of the Kentish hedge-priest John Ball was mentioned as being one of the Upright Men. Judgements were made on him and opinions passed. Athelstan kept his head down as if more interested in his food. The friar quietly prayed that his views would not be asked. Many of his parishioners were fervent adherents of the Great Community; Pike the ditcher for one sat very close to some of the most zealous of the Upright Men. Cranston, wolfing down his food, caught the friar’s unease and deftly turned the conversation to what Athelstan had told him about the prisoner condemned to hang the following morning.

‘A notorious river pirate,’ Abbot Walter pronounced, feeding Leda whilst smiling at his niece.

The abbot went on to describe other depredations of this well-known felon. Athelstan just picked at his food, secretly wishing he could take the entire banquet back in baskets for his parishioners. The friar lifted his head and quickly gazed round. He was certainly learning more about this abbey. He caught the mutual dislike between Abbot and Prior, which he recognized as truly rankling. Isabella, the abbot’s niece, seemed rather vapid and flirtatious. Athelstan wondered about her true relationship with the abbot yet the more he stared at her his conviction only deepened that a strong blood tie existed between the two. The elder woman, Eleanor, was at first tight-lipped but, as the wine flushed her face, she relaxed, becoming quite chatty, a highly intelligent woman, sharp-witted with a keen mind, who shrewdly commented on different matters. However, Athelstan noticed that the more she talked the more Cranston seemed fascinated by her, staring across the table as if trying to recall something. Athelstan took advantage of the servants clearing the table for the final course of sweetened tarts crowned with cream, to pluck at the coroner’s sleeve and whisper what was the matter?

‘I know her,’ Cranston murmured, dabbing his mouth with a napkin. ‘Friar, I am sure I do. A face from my past but I cannot place her.’

‘Has she recognized you?’

‘No, no. Ah well, what a strange place!’ He leaned closer. ‘Well, Friar,’ Cranston whispered. ‘When you were mumbling your prayers I despatched one of the lay brothers to His Grace the Regent at his Palace of the Savoy-’

Athelstan abruptly gestured for silence. The table conversation had now changed. Mistress Eleanor was asking about the murders amongst the Wyverns. Abbot Walter immediately assured her that he could not explain the deaths but added that they might be the work of malefactors from the river.

‘The Wyverns suspect me,’ Richer declared abruptly. ‘They think I am waging a feud over the Passio Christi.’

‘Are you?’

‘You asked me that before, Brother Athelstan. As I answered then, I am a Benedictine.’

‘You also served under the Oriflamme banner,’ Cranston declared. ‘You’ve been a mailed clerk, yes?’

Richer did not disagree.

‘So why have you come here – the truth?’

‘I have already explained.’

‘Brother Richer is a peritus,’ Abbot Walter retorted, shooing off his pet swan. ‘He has done excellent work in our library and scriptorium but. .’ Abbot Walter smiled maliciously at Prior Alexander, whose jibe about his beloved Leda he’d not forgotten. ‘Perhaps, with all our many problems here, Brother Richer, it’s time you returned to St Calliste. I mean,’ Abbot Walter waved a hand, ‘sooner, rather than later?’

Richer simply shrugged. Prior Alexander, however, sat rigid, his wine-flushed face tense with anger.

‘Brother Richer,’ Athelstan intervened swiftly, ‘which manuscripts. .’ His words were cut off by a sharp knock on the door. A servitor hurried in and whispered into Abbot Walter’s ear.

‘Bring him in, bring him in,’ the abbot insisted. ‘Sir John, a messenger – Kilverby’s man, his secretarius, Crispin.’

The arrival of the sad-eyed clerk eased the tension. The two ladies immediately rose and said they must retire, as did Prior Alexander who gestured at Richer to follow suit. As they left Crispin was ushered in. He assured Prior Alexander that his eyesight had at least not worsened and he was grateful for all his advice. Once the door was closed, Crispin was offered a vacant seat, Abbot Walter insisting he drank some white wine and eat a little of the cream tart. Crispin did so, muttering between mouthfuls how he and a manservant had travelled by horseback as the river had become swollen and turbulent.

‘Never did like the Thames at night.’ He cleared his mouth.

‘Crispin, what will you do now Sir Robert is so pitifully slain?’ Abbot Walter asked.

Crispin shook his head. ‘I have sworn to perform some act of loyalty to my dead master. Perhaps I might go on pilgrimage as Sir Robert wanted to do. I could fulfil his vow at Rome, Santiago and Jerusalem. Yes,’ he smiled bleakly, ‘that’s what I should do; after all, my master has gone and Mistress Alesia has her own plans.’

‘You’ll still be most welcome here,’ Abbot Walter reassured him.

Crispin thanked him and turned to Athelstan and Cranston.

‘I came here,’ he declared, ‘because I had to. His Grace the Regent came to our house.’ Cranston groaned and put his face in his hands.

‘Sir Robert’s chamber was not unsealed, was it?’ Athelstan asked.

‘No, no, His Grace was most strict on that but his temper was very sharp. He had the rest of the mansion searched from cellar to attic but they found nothing. His Grace also sent you this.’ Crispin drew from his wallet a small scroll sealed with wax. Cranston snapped the letter open and swore under his breath, forcing Abbot Walter, more interested in his beloved Leda, to glance up sharply.

‘And there’s more, isn’t there?’ Athelstan asked Crispin. ‘You bring other news?’

‘Master Theobald the physician has scrutinized Sir Robert’s corpse most thoroughly. Some potion stained his lips and created blueish-red marks here.’ Crispin gestured at his own thin chest and sagging belly. ‘Master Theobald also declared that the wine and sweetmeats were not tainted but he detected a smell from Sir Robert’s corpse which seemed to grow stronger after death: the odour of almonds.’

‘The juice of almond seed.’ Abbot Walter had now forgotten his swan. ‘We have some of that juice here. Prior Alexander would recognize it. I am glad however that the sweetmeats, our gift to Sir Robert, were not tainted but his death is so odd, so curious. Now sirs, please excuse me.’ The abbot, dabbing his sweaty, porkish face with a napkin, rose to his feet, sketched a blessing in their direction and, followed by Leda, swept out of the chamber.

Cranston broke the ensuing silence by drinking noisily from his goblet, then held up the Regent’s letter.

‘Worse and much worse to come, little friar.’

‘Sir John?’

‘The Regent must be obeyed on this,’ Cranston declared. ‘Crispin and I will leave for the city. Yes, we’ll go now even though it is dark. The city guard will let me through. In truth, I prefer to sleep in my own bed with my plump wife beside me.’

‘And me, Sir John?’

‘You, Friar, have drawn the short straw on this. His Grace insists that you stay here until this business be finished.’

Athelstan, his cowl pulled well over his head, stood by the gate which led from the abbey gardens overlooking Mortival meadow. It was certainly a morning for a hanging: sombre, grey and mist-filled. The sounds of the abbey remained muffled and distant, be it the clanging of bells, the lowing of cattle or the strident cries of geese and cockerels. Sir John and Crispin had left immediately the night before, the coroner borrowing a mount from the abbey stables. Cranston was visibly shaken by the Regent’s apparent temper and, as he whispered to Athelstan in the stable yard where they made their farewells, there was much to reflect upon about this abbey, especially Eleanor Remiet. Athelstan had watched Cranston go. Later in the evening the friar had been given a warm chamber in the abbot’s own guest house. There he tried to marshal his thoughts but tiredness overtook him and he fell asleep to dream about his own sojourn in France. Awake long before dawn, Athelstan sang prime with the brothers and celebrated his Jesus Mass in a side-chapel. Now he was here to glimpse the anchorite, who also served as the abbey hangman.

A bell began to toll the death-knell, booming solemnly, announcing to the world that another soul was about to meet its God. The refrain of the ‘ De Profundis’ wafted on the breeze. The glow of candle sparked through the swirling mist. Out of this came the crucifer grasping a wooden cross, either side of him the acolytes carrying their capped candles, followed by a thurifer filling the air with incense. Prior Alexander followed. A cowl concealed both his head and face, hands pushed up the sleeves of his gown. He recited the death psalm which was repeated by the group of brothers huddled behind him. The anchorite, garbed in a monk’s robe, came next; the thrown back hood revealed a cadaverous, clean-shaven face framed by straggling hair the colour of straw which fell down to his shoulders. In one hand this sinister-looking individual carried a crucifix and in the other a coil of rope. Behind him lay brothers on either side bore a coffin and a set of ladders. The closely guarded prisoner came next, his mask now removed. Athelstan stared at that reddish, furrowed face, scrawny hair and the scars along his neck.

‘Fleischer the fisherman!’ he exclaimed. The prisoner paused and stared at the friar, who pushed back his cowl.

‘Brother Athelstan, you’ve come to see me dance on air.’

The entire procession stopped. Prior Alexander, intrigued, walked back. ‘You know this felon, Brother?’ the prior asked.

‘Oh, yes.’ Athelstan gazed at Fleischer. He certainly knew the fisherman. A bosom friend of Moleskin the boatman, Fleischer sometimes appeared on the shabby quaysides of Southwark to participate in the rich harvest of mischief to be found along its filthy runnels and alleyways: robbery, smuggling and counterfeiting. Fleischer was as attracted to such devilry as Bonaventure to a dish of cream.

‘I would like words with you, Brother?’

Athelstan glanced at Prior Alexander, who nodded. The anchorite pushed Fleischer across.

‘Your prisoner, Brother.’

‘ Pax et bonum.’ Athelstan stared into the glassy, blue eyes of the anchorite. Was he mad, touched by the moon? No, Athelstan reckoned, the anchorite was only agitated. Athelstan also caught the glint of humour in the man’s strange, pallid face.

‘For a short time he is yours.’ The anchorite stood back. ‘And then he’ll be mine again.’

Athelstan gently led Fleischer out of hearing.

‘You want to be shriven?’

‘I’ve confessed,’ Fleischer replied. ‘Give me your blessing.’

Athelstan did so.

‘Will you sing a Mass for me, Brother, that my journey through the flames won’t be too long?’

‘Of course.’

‘Give Moleskin and the rest greetings.’ Fleischer tried to curb his tears. ‘I was born into wickedness, Brother, no mother or father, alone with all the other rats.’ He stared around. ‘I didn’t mean to kill the monk but I was desperate. Strange.’ Fleischer ignored Prior Alexander’s cough as he shuffled from foot to foot. ‘Here I am,’ Fleischer stepped closer, his ale-tinged breath hot against Athelstan’s face, ‘being hanged by the Lord Almighty Abbot – you’re here for the murders, to probe and snout for the killer?’

‘You could say that, my friend.’

‘Then take a good look at these shaven heads. I’ve seen the Frenchman Richer meet boatmen from foreign ships – what is that, treason? And as for Prior Alexander, he so likes being with his good friend the sub-prior, even if it means travelling along a freezing river in a barge. Or shall we talk about those good monks who don disguises and visit the stews and bath houses of Southwark? For me retribution is close but theirs is also approaching. When the great revolt breaks out and it will, like pus from a sore, believe me, all the Marybread and Marymeat distributed on a Sunday won’t save them. They’re all as rotten and wicked as I am.’

‘Scurrilous rumours, my friend?’

‘Perhaps, Brother.’ Fleischer looked over his shoulder. ‘As for Lord Walter! Sharing the kiss of peace with the Upright Men who gather at All Hallows won’t protect him.’ Fleischer grinned bleakly. ‘Ask any of the river people. Anyway, these mumbling mouses now want to hang me.’ He nodded back at the anchorite, standing like some sombre statue. ‘At least they say he’s good. He can do it in a splice – he’s not some cow-handed peasant. Ah well, I’m getting cold and it’s time I was gone.’ He bowed his head. Athelstan made the sign of the cross over him and stepped back as the anchorite came over.

‘I would like words with you, sir,’ Athelstan murmured, ‘when this business is finished. I shall be waiting for you in St Fulcher’s chantry chapel.’

The anchorite simply darted a look, grasped Fleischer by the arm and took him back to join the others. The procession reformed. Prior Alexander intoned the opening words of the sequence, ‘ Dies Irae– Oh Day of wrath, Oh Day of Mourning, See fulfilled heaven’s warning. .’ The sombre sight disappeared into the thick veil of mist. The candle light dimmed, the words faded, nothing but silence. Athelstan sighed, blessed himself and walked back through the murk into the abbey church. All lay quiet. This hymn in stone closed around him, evoking memories of his motherhouse at Blackfriars. Athelstan compared its magnificence with the simple crudeness of St Erconwald’s and felt a pang of homesickness. He would love the likes of Huddle, Watkin and all that boisterous throng to come tumbling through the porch. Athelstan reached the chantry chapel. He went in under the latticed screen with its fretted carving and sat down on a stool staring up at the painted window, marvelling at the sheer subtlety of it all. A demon had been drawn into its intricate tracery. Red stain had first been applied to the blue glass whilst the glowing left eye of the fiend had been formed by simply drilling the actual glass. The devil’s yellow, spiky hair was depicted against a background of flaming red which reflected the very fires of hell.

Athelstan glanced down at the floor. He must concentrate on why he was here. He must summarize what he’d learnt then revise and draft it as he used to before debating a theological problem at Blackfriars.

Item: Sir Robert Kilverby had apparently retired to his chamber hale and hearty. The Passio Christi was safely locked away in its coffer and kept in that chamber.