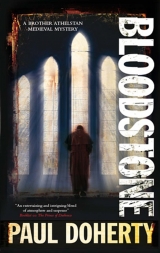

Текст книги "Bloodstone"

Автор книги: Paul Doherty

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Cranston, sipping his wine, noisily cleared his throat to speak when the door abruptly opened and the largest swan Athelstan had ever seen waddled pompously into the chamber. The bird’s webbed feet slapped the polished floor, its long elegant neck arched, the oval-shaped head of downy white and black-eyed patches ending in a yellow bill which opened to cry eerily as the bird fluffed snow-white feathery wings. The swan headed straight for the abbot. Cranston made to rise. The swan turned, hissing furiously, glorious wings unfolding.

‘It’s best to sit down,’ Prior Alexander declared wearily. ‘Leda only answers to Father Abbot.’

Cranston resumed his seat and the bird continued on to receive food from the abbot’s hand before nestling on soft cushions in the corner. Cranston just glared at the bird as Abbot Walter explained how Leda had been his special pet since a hatchling.

‘A change from the monkeys, apes and peacocks,’ Prior Alexander breathed, ‘not to mention the marmosets, greyhounds and lap dogs.’

‘All God’s creatures,’ Abbot Walter commented cheerfully, ‘all gone back to God.’

‘There’s even a small place in God’s Acre for God’s own creatures.’ Prior Alexander could not keep the sarcasm out of his voice.

‘All God’s creatures,’ Cranston echoed sharply, ‘and there’s two more for God’s Acre, former soldiers who lodged here, Gilbert Hanep and Ailward Hyde brutally despatched to judgement before their time and,’ Cranston now had the monks attention, ‘I bring you the most distressing news. You expected the Passio Christi to be brought here this morning by Sir Robert Kilverby’s steward Crispin, together with his daughter and son-in-law?’

‘Yes, we wondered. .’

‘Murdered!’ Cranston retorted. ‘Sir Robert was foully poisoned in his chamber and the Passio Christi has disappeared.’

Abbot Walter almost choked on his wine. Prior Alexander sat back clutching the arms of his chair, mouth gaping in surprise. Richer stared in disbelief at both Cranston and Athelstan then glanced away, shaking his head. Once they had recovered, Cranston, ignoring their questions, pithily informed them what they had learnt at Kilverby’s house.

‘So,’ Cranston concluded. ‘Did Sir Robert share with you his intention to leave the Passio Christi here at St Fulcher’s on the very day he left on pilgrimage?’

‘That,’ Abbot Walter waved a hand, ‘may have been in his mind but,’ his fat face creased into a smile, ‘I cannot comment on what Sir Robert intended or what might have been. Sir Robert is now dead. The Passio Christi is missing, then there are the deaths here.’

‘Murders,’ Athelstan broke in. ‘Father Abbot, two of the Wyvern Company have been foully slaughtered in your abbey.’

‘My Lord of Gaunt has heard of the first death,’ Cranston added, ‘when he hears of the second, not to mention the murder of Sir Robert and the disappearance of the Passio Christi, his rage will know no bounds.’ Cranston’s words created a tense silence. His Grace the Regent was not to be crossed, even by Holy Mother Church.

‘I would not be surprised,’ Cranston added softly, ‘if His Grace did not honour you with a visit, Lord Walter, but now, reverend fathers, these murders?’

Prior Alexander replied. He assured Sir John how the Wyvern Company were happy, as they had been for the past four years. They’d claimed the Passio Christi was their find, so twice a year they were allowed to both view and hold it. For the rest, Sir Robert paid the abbey through the exchequer a most generous amount so the former soldiers enjoyed very comfortable lodgings.

‘Until now?’ Athelstan declared.

‘Yes, early this morning just after first light, Brother Otto who tends the cemetery went for his usual morning walk. Gilbert Hanep’s corpse was found near the grave of his old comrade William Chalk.’

‘Another death?’

‘By God’s good grace, in the order of nature,’ the prior replied. ‘William Chalk was sickening for some time from tumours in both his belly and groin.’

‘So Hanep rose in the middle of night to pay his respects to this dead comrade?’

‘Brother Athelstan, Hanep, like his comrades, was a veteran, a warrior, a professional soldier. He was restless, much given to wandering this abbey at night.’

‘And someone who knew that was waiting? His assassin must have followed him down to the cemetery and killed him?’

‘Took his head, Brother, a swinging cut; those who found him were sickened by the sight.’

‘And no indication or evidence for the murderer?’

‘The ground was awash with blood,’ Prior Alexander retorted, ‘but no one saw or heard anything untoward.’

‘And late this afternoon, Ailward Hyde was murdered near the watergate.’

‘A vicious wound to the belly,’ the prior replied, ‘the poor man’s screams rang across the abbey. By the time our good brothers reached him he was dead, soaked, almost floating in his own blood.’

‘Why?’ Cranston asked. ‘Why now?’

‘Sir John, we truly don’t know.’

Was there a link? Athelstan reflected, staring at the carved figure of a seraph carrying a harp on the right side of the fireplace. Was Sir Robert’s death, the disappearance of the Passio Christi and the murder of these two unfortunates all connected, or was it something else? Athelstan shivered. He recalled a lecture by Dominus Albertus in the schools so many years ago. How every evil act like seed in the ground eventually blooms to manifest its own malevolent fruit. Wickedness was like a tangled bramble, cruel and twisting, breaking through the soil, stretching out to create its own trap. Kilverby had enjoyed the reputation of being a hard-fisted money lender, notorious throughout the city and Southwark. Members of the Wyvern Company had killed, pillaged and plundered, even seizing a precious relic for their own greedy uses. Was this their judgement day, ‘their day of wrath, the day of mourning’ as described by the poet Thomas di Celano? Had the victims of all these murders been caught out by their own wickedness sown so many years ago? ‘Everything sown will be reaped’, or so ran the old Jewish proverb. Had harvest time now arrived?

‘Brother Athelstan?’

‘Sir John.’ Athelstan rose to his feet. ‘I have other questions but they will wait. We should view the corpses and question the Wyvern Company. After all, the day is drawing on and my parish awaits.’

‘Your parish?’ Prior Alexander’s voice was harsh. ‘Brother Athelstan, we know of you, a Dominican sent to do penance. .’

‘Then if you know,’ Cranston declared, getting to his feet, ‘there’s little point in retelling it.’ He bowed perfunctorily in the direction of the abbot. ‘Reverend Father, if we can view the corpses?’

Richer led them out of the abbatial enclosure and into the main cloisters. The day was drawing on and the monkish scribes working in their carrels around the cloister garth were collecting their writing equipment in obedience to the bell tolling for the next hour of divine office. Athelstan drank in the sights, watching the scurrying black-robed monks, as organized as any cohort in battle array, prepare for the next task. Other brothers were coming in from the field, doffing their aprons, shaking off their hard wooden clogs and gathering around the different lavaria to wash and prepare themselves. Athelstan wanted to speak to Cranston but Richer kept close as he led them across the abbey. At last they reached a deserted, cobbled yard. Richer ushered them into the whitewashed death house where two coffins rested on trestles beneath a crude black crucifix nailed to the wall. Six purple candles on wooden stands ringed each coffin. Beneath these, fire pots containing crushed herbs exuded a pleasant smell to counter the reek of corruption and decay. A gap-toothed, balding lay brother, hands all a flutter, came out of a shadowy recess to introduce himself. Richer curtly ordered him to raise the deerskin coverlets drawn over both corpses. Once done Athelstan gazed down at both cadavers. Hanep’s head had been sown back on with black twine but the face seemed to have shrunken and shrivelled like a decaying plum. Hyde’s cadaver was still cloaked in congealing blood, the great slit across his belly crammed with scented linen rags.

‘I’ve yet to wash him,’ the keeper of the dead declared mournfully.

Athelstan leaned over and studied the gruesome wounds.

‘Friar?’

‘Sir John, look,’ Athelstan pointed, ‘here’s the gash, the death wound but look, another piercing here.’ He motioned further up the belly. ‘The assassin made a sweeping cut, turning the blade of his sword to skewer his victim’s innards, a killing cut but then withdraws the sword and plunges it again.’

‘And?’

‘The assassin must have enjoyed that, for one slash would have been enough. Hyde’s screams were immediate yet the killer stays for a second thrust.’ Athelstan stepped back; his boot caught something beneath the trestles. He stooped down and dragged out the war belts, swords and daggers in their sheaths.

‘The victims,’ Richer declared.

‘Wearing sword belts in an abbey?’

The sub-prior made a face.

‘When Hyde’s corpse was found, were his weapons sheathed?’

‘He was holding both sword and dagger,’ the keeper of the dead offered. ‘I was there when we found him slumped against the curtain wall near the watergate.’

Athelstan carried the sword belt into a pool of lantern light. He drew both weapons; their blades were clean though flecks of blood stained the hilts where Hyde must have held his weapons close. Athelstan placed the war belt back.

‘And Hanep carried weapons?’

‘Yes,’ the keeper replied, ‘but I do not know whether they were sheathed or not.’

‘And why should Ailward Hyde go down to the watergate?’

‘I don’t know, Brother,’ Richer was quick to answer, ‘but his presence there might indicate that his killer came from the river rather than the abbey.’

Athelstan had seen enough. He put down the perfumed pomander the lay brother had thrust into his hand and walked back into the darkening day. He stood listening to the different sounds of the abbey whilst Cranston took a generous sip from his wineskin.

‘You will meet the members of the Wyvern Company?’ Brother Richer’s dislike of the former soldiers was obvious; his handsome face was twisted in contempt, his English almost perfect except for the slight accent now coming through.

‘They’re all assembled in the refectory of their guest house where they will, as usual, be slurping their ale and boasting about their sins.’

‘Brother, you must resent these men? You come from the Abbey of St Calliste near Poitiers. You believe your abbey was plundered by these men?’

‘Before my day,’ Richer dug his hands up the sleeves of his robe, ‘long before my day, but yes, I resent them. They are pillagers, ravishers, sacrilegious miscreants. If they’d not been on the side of the victors they’d have been hanged out of hand. Brother, why talk here in the freezing cold?’ Richer led them away from the gloomy death house, back into the main buildings. He waved them into a small visiting chamber warmed by two braziers and lit by a huge lantern-horn; they sat around a small table, Richer pulling one of the braziers closer.

‘Brother Athelstan, Sir John,’ Richer smiled, ‘I’m French through and through. I do not believe that the English Crown has any right to that of France but,’ he held up a slender hand, ‘I’m also a Benedictine. Our houses stretch across Europe and beyond. Here at St Fulcher are English, French, Bretons, Hainaulters, Castilians and Germans. One thing binds us: we have all put away our former selves and donned the black robes and accepted the rule of our master St Benedict.’

‘But why are you here?’

‘Because I’m a scholar, Sir John, a bibliophile, a peritus – how do you say? An expert in the care and use of precious manuscripts. I have visited the great libraries of Rome, Avignon and St Chapelle. Three years ago Abbot Walter asked my superiors in France for assistance with the great library here and çela,’ he spread his hands, ‘I am here.’

‘I’ll be blunt, Richer. Did you come here with secret orders to seize the Passio Christi?’

Richer grinned. ‘I’m a Benedictine, Sir John, a librarian. True,’ he conceded, ‘I would love to take the Passio Christi back to St Calliste but, if rumour is true, that was about to happen anyway. I mean, if Sir Robert left it here before journeying on pilgrimage, it would have only been a matter of time before our precious bloodstone passed back into the rightful hands.’

‘You apparently don’t believe the story how the Wyvern Company found the Passio Christi on a cart, along with other precious items, on a deserted road near the Abbey of St Calliste?’

‘No, Brother, I certainly don’t and I suspect, neither do you. A farrago of lies! I was a novice at St Calliste. I followed my vocation there. I’ve heard the stories. The battle at Poitiers was truly a disaster for the power of France. In the days following, English free companies roamed the fields and highways pursuing their enemies and helping themselves to whatever they wanted. St Calliste should have been sacred but a group of ruffians wearing the Wyvern livery scaled the walls and wandered the abbey. The Passio Christi was kept in a tabernacle in a small chantry chapel to the right of our high altar.’ Richer’s face grew flushed, his voice more strident. ‘It should have been safe there, a sacred relic in a most holy place! The House of God, the Gate of Heaven! Yet it was stolen, along with other precious items.’

‘Have you ever confronted the Wyverns with their crime?’

‘Of course, Brother Athelstan, just once. I was mocked and ignored.’ Richer snorted with laughter. ‘Do you think these ribauds are going to confess to sacrilegious theft? I told them if they were guilty of that then they incurred excommunication, ipso facto, immediate and swift. You know, Brother Athelstan, such an excommunication can only be lifted. .’

‘After three steps have been taken.’ Athelstan recalled the relevant decree. ‘Restitution, reparation and an absolution by a priest.’

‘ Tu dixisti!’ Richer quipped. ‘You have said it, but those ribauds will never confess the truth.’

‘And Sir Robert, he often visited St Fulcher for spiritual consolation?’

‘Four or five times a year.’ The sub-prior shook his head. ‘Sometimes I’d talk to him, a strange man much taken up by the state of his soul. Of course I cannot speak about that. I am sorry to hear he died un-shriven but I can say little. He did most of his business with either Abbot Walter or Prior Alexander. If he spoke to me it was on spiritual matters and that is my concern.’

‘And the Wyvern Company – have they changed recently?’

‘If they have, I’ve hardly noticed. They keep to themselves. Prior Alexander might help.’

‘When Hanep and Hyde were murdered they were still wearing their sword belts – why should they go armed here in a peaceful abbey?’

‘Very observant, Brother Athelstan.’ Richer wagged a finger. ‘By the way, we have heard of you here, an indefatigable seeker of the truth.’

‘Praise from a Benedictine is praise indeed,’ Athelstan retorted, keeping an eye on Cranston, who looked on the verge of sleep. ‘But my question?’

‘I don’t know. Perhaps they feared each other. Perhaps some relict from their past outside this abbey has intervened.’

‘You mean,’ Cranston shook his head, smacking his lips, ‘someone from outside is responsible for their murders? Surely a stranger would soon be noticed here?’

‘Not at the dead of night, Sir John, or on a dark December afternoon with the river mist curling around the abbey. Even worse if the assassin donned the black robes of a Benedictine.’ Richer rose to his feet. ‘Perhaps some ancient, unresolved blood feud, God knows. Such men must have made enough enemies in life. Come, let them tell you themselves.’

They left the petty cloisters, darkness was falling. Athelstan plucked at Cranston’s cloak. ‘We should be gone!’

‘In a while.’ The coroner seemed evasive, lost in thought and strode swiftly after the sub-prior. Most of the brothers were now in the abbey church. Silence lay like a pall across the precincts and gardens. Athelstan paused at the welling sounds of voices chanting a psalm from the divine office: ‘ Vindica me Domine et judica causam meam —Vindicate me Lord and judge my cause’. Aye, Athelstan thought, do so, Lord, for this truly is a maze of lies and deceit. They passed the Galilee porch; a coffin stood there. Athelstan recalled what he’d glimpsed in the death house. He paused and abruptly asked Brother Richer to show them where both men had been murdered.

‘Must we?’ the sub-prior protested. ‘Brother, this day has proved hard enough.’

‘Please?’ Athelstan glanced quickly at Cranston. ‘The coroner is supposed to view the place of death.’

‘The King’s coroner has no jurisdiction in an abbey.’

Cranston stopped, grasped the sub-prior by the shoulder and gently turned him. ‘My friend,’ Cranston pushed his face close to Richer’s, ‘trust me on this if nothing else. I do have jurisdiction here for if the Lord Almighty John of Gaunt wants it, then that is the law!’

Richer swiftly apologized and led them across into the gloomy cemetery. He showed William Chalk’s grave with its raw mound of earth. Above it a wooden funeral cross on which were carved the former soldier’s name and date of death with the words: ‘ Requiet in luce– Let him rest in light’, etched beneath a crude carving of a dragon-like creature.

‘Gilbert Hyde came here.’ Athelstan crouched. ‘He did what I am doing now.’ He then turned, straining his neck, his outline clear in the faint light. The assailant was undoubtedly a professional swordsman, a master-at-arms. He took Hyde’s head in one clear cut. ‘Come.’ Athelstan rose, pulling his cloak closer about him.

Richer, grumbling under his breath, led them out of the cemetery across the abbey and into Mortival meadow. The broad field now looked bleaker in the gloaming, the mist still swirled, crows called raucously from the trees. The wind had turned sharper, more vigorous tugging at hood and cloak; the frozen, icy grass scored their ankles.

‘A field of ghosts,’ Athelstan whispered.

They reached the watergate. Athelstan crouched to study the place where Hyde had died, his blood flecking the curtain wall.

‘Why was he here?’ He peered up at Richer. ‘Why was an old soldier armed with a sword down here at the watergate? To meet someone? Did his assailant come by boat, kill him then flee? Or did someone in the abbey follow him down here and strike the killing blow? Yet there were two assailants, I’m sure of that, two not one, but how did the assailants kill and escape?’ Athelstan couldn’t make out Richer’s face; the monk’s cowl and the poor light made it difficult to discern any expression. Athelstan touched the wall, then went through the watergate on to the mist-hung quayside, a bleak place especially with the black three-branched gallows soaring above them. Glowing braziers shed some light. Athelstan crouched, peering at the ground, scratching it with his fingernail, then he walked back stopping now and again to do the same. He swiftly recited the ‘ Veni Creator Spiritus’ and stood up.

‘Very well, I have seen enough. .’

The Wyvern Company, all four of them, were assembled in the beam-raftered, whitewashed refectory in the main guest house, a long room with a roundel window at the far end; lancet windows pierced one wall whilst a narrow hearth stoked with fiery logs stood in the centre of the other. The floor was covered with green supple rushes. A common trestle table ran down the centre of the refectory with benches either side. The former soldiers sat grouped at the top of the table, whispering amongst themselves as they shared a jug of ale and a platter of bread and cheese. They hardly moved when Richer entered and introduced Cranston and Athelstan. Rugged, hard men, all four looked what they were – veteran soldiers who’d served the god of war for many a year, their furrowed, clean-shaven faces burnt by sun and wind, narrow-eyed, thin-lipped, heads shorn. They ate and drank slowly, savouring every mouthful, eyes watchful. They were dressed alike in thick woollen jerkins and cambric shirts. War belts lay close to their soft, booted feet.

‘Well, my paladins of old, if you don’t want to stand as a courtesy for Holy Mother Church,’ Cranston leaned all his considerable bulk on the end of the table, ‘I suggest you do so for the King’s High Coroner, confidant of His Grace, John of Gaunt and former veteran of the illustrious King’s, not to mention his equally illustrious son Edward the Black Prince’s wars against the French.’ His voice rose. ‘By the grace of God, Sir John Cranston, Officer of the Crown.’

One of the company raised a badly-maimed hand, grunted and rose slowly to his feet; the rest followed. They all clasped Cranston’s now outstretched hand, nodded at Richer and Athelstan then sat down, their insolence barely concealed by their reluctant courtesy. Cranston took Athelstan to the other end of the table. He sat on the high stool with Athelstan and Richer either side, forcing the soldiers to turn and shuffle awkwardly towards them.

‘The day is dying,’ Cranston smiled, ‘and we are all waiting for the dark which comes sooner or later. Well, you know who I am. Who are you?’

Richer swiftly introduced the four former soldiers: Richard Mahant, Fulk Wenlock, Andrew Brokersby and Henry Osborne. Once he had their attention, Cranston briefly described what had happened in the city – the mysterious death of Kilverby and the disappearance of the Passio Christi. All four were shocked and surprised, although Athelstan suspected that since they’d already told the abbot such news would spread swiftly in an enclosed community.

‘It does not affect us really.’ Fulk Wenlock raised his right hand, the two forefingers savagely cut off at the stump. ‘The Passio Christi was surety for our comfortable quarters here, but I am sure my Lord of Gaunt will honour the Crown’s pledges.’

‘True, true,’ Cranston considered. ‘But where were you all yesterday – here?’

‘No,’ Wenlock retorted, ‘not all of us. Mahant and I left in the afternoon for the city.’

‘Why?’ Athelstan asked.

‘Our business, Friar, but if you want to know to roister, to drink and I had petty business with a goldsmith in Poultry.’

‘His name?’

‘John Oakham.’

‘Which tavern did you lodge at?’

‘The Pride of Purgatory.’

‘I know it well,’ Cranston replied. ‘Large and sprawling. Minehost is famous for his stews.’

‘And you returned?’ Athelstan asked.

‘Late in the afternoon. We immediately heard the news of poor Ailward’s death.’

‘And you?’ Athelstan turned to Osborne and Brokersby. ‘Where were you when Hanep was murdered?’

‘Asleep in our beds, Friar.’

‘And when Master Hyde was murdered down near the watergate?’

‘We were here together.’ Osborne’s voice portrayed a strong burr. ‘We were eating a slice of venison pie and a dish of vegetables.’

‘So why was Hyde wandering Mortival meadow?’

‘We don’t know,’ Brokersby retorted, ‘nor do we know why Hanep was murdered out in the cemetery. For God’s sake, Priest,’ Brokersby brought his hand down flat against the table, ‘we truly don’t know. Hanep could never sleep; he loved to wander at night.’

‘That’s true,’ Richer intervened. ‘Master Hanep’s nightly pilgrimages around this abbey were well known.’

‘Yet both men were murdered,’ Athelstan continued remorselessly, ‘executed by a skilled swordsman. Indeed, Master Ailward may have been murdered by two assailants. Why?’

‘We don’t know,’ Wenlock spoke up, ‘we truly don’t. Matters between us were most amicable. We have served together for decades. We have fought, starved, been threatened and survived.’

‘We come from the same manor in Essex,’ Brokersby explained, ‘Leighton, on the way to Wodeford. We became master bowmen and joined the Company of Edward the Black Prince. We took the Wyvern as our livery. .’

‘Continue.’ Athelstan smiled.

Brokersby described how he and his companions, at least two score in number, fought in France under the Wyvern banner, about their allegiance to Prince Edward and their undying adoration of him. Athelstan warned Cranston with his eyes to remain silent, for these men needed little encouragement to wax lyrical about their exploits in the Poitiers campaign when they had shattered the power of France. Brokersby mentioned how he’d once been a scholar, a would-be cleric, educated in the local church of St Mary’s. Indeed, he added, he was writing his own chronicle of events. This caused surprise even amongst his companions. So, as darkness descended and the bells sounded for the next hour of divine office, the old soldiers reminisced. Athelstan listened and closely studied these grey-haired warriors with the archer braces still on their wrists. Once these were the scourge of France, men who feared no enemy. He also concluded that Mahant was their leader, Wenlock their adviser. More ale was supped. Cranston joined in with his own memories as Richer politely excused himself and withdrew. Once the Frenchman had closed the door behind him Cranston tapped the table for silence.

‘So we come to the Passio Christi,’ the coroner declared. ‘Did you steal it? Of course if you did you are excommunicated, cut off from the church. You shouldn’t even be here in these hallowed precincts.’ He sighed. ‘Naturally you’ll deny that. Anyway, tell us, how did you find the bloodstone?’

‘To be as blunt,’ Wenlock retorted, ‘after Poitiers we swept the fields like a windstorm, the very fires of hell.’

‘In other words you plundered and pillaged?’ Cranston barked. ‘I was there, you know. I took part in it. Our army was full of vagabonds, runaways, rascals and ribauds, the scum of our prisons who came from slums so horrid even the rats hanged themselves.’ Cranston’s words were greeted with silent disbelief until Wenlock beat the table with a maimed hand, bellowing with laughter.

‘True, Sir John.’ He glanced around his companions. ‘Come on, that is the truth! We had cozeners, tumblers, ape-carriers.’ His words won nods of approval. ‘However, we were master bowmen,’ all the good humour drained from Wenlock’s face, ‘and the Passio Christi was found in a casket on a cart along a leafy country lane.’

‘By you?’

‘By us, Friar.’

‘And what else was in that cart?’

‘Some cloths.’ Wenlock paused. ‘Cups, mazers, a few manuscripts.’

‘And you surrendered all of this to Edward, the King’s son?’

‘We did.’

‘And?’ Athelstan persisted.

‘An indenture was drawn up. You can study it at the Exchequer of Receipt. .’

‘I have,’ Cranston interrupted.

‘We were given an allowance every month. The jewel was to be held by Kilverby, the Prince’s treasurer. You know the rest so why should we tell you?’

‘How long have you been here?’ Athelstan asked, fighting off the weariness of the day.

‘About four years. We came from France then did guard duty at the Tower, Sheen, Rochester and King’s Langley. Five years ago we petitioned the Crown. We were promised corrodies here.’

‘And why St Fulcher’s?’

‘Ask Father Abbot, Sir John. The old King and his son, before they left London for Dover and their chevauchées through France, stopped here to light tapers. They arranged for Masses to be sung to Christ, Our Lady of Walsingham, and all the saints that God would favour the Leopards of England. The old King even founded a chantry chapel here dedicated to St George.’ Wenlock pulled a face. ‘St Fulcher received other gifts and endowments from the royal family.’ Wenlock gazed over his shoulder at the capped hour candle on its stand in the far corner of the refectory. ‘Sir John, Brother Athelstan, the day goes and so must we.’

‘Richer,’ Athelstan moved his writing tray, ‘do you find him hostile? After all, he is from the Abbey of St Calliste which once held the Passio Christi?’

‘They claim they once held it,’ Wenlock replied. ‘We have no real proof that the bloodstone we found belonged to that abbey. I mean, if it was,’ he smiled, ‘why was it outside the abbey on a cart?’

Athelstan gazed at these former soldiers. He recalled how he and his brother consorted with such men, practical and pragmatic without any real interest in religion or indeed anything else outside their own narrow world. Wenlock’s blunt language was typical.

‘Was the cart abandoned?’ Athelstan asked. ‘What happened to its escort?’

‘By all the saints,’ Brokersby exclaimed, ‘that was years ago! What does it matter now?’

‘Because, my friend,’ Cranston shouted back, ‘if it was proven, even now, that the Passio Christi was stolen from the Abbey of St Calliste that renders you excommunicate, whatever the number of years. You would still be proclaimed public sinners and stripped of everything. You might even hang. So tell us,’ Cranston added quietly.

‘We found it in a cart,’ Wenlock answered coolly.

‘No escort?’

‘Nothing, just plunder of war waiting to be taken.’

Athelstan sighed noisily. ‘That is your story.’

‘We are our own witnesses,’ Mahant declared. ‘Who else is there?’

‘Tell us,’ Cranston asked, ‘why should two of your company be so barbarously slain?’

‘We don’t know,’ Osborne declared.

‘We are old soldiers serving our time,’ Mahant added.

‘So why go armed in this abbey?’

‘Because Sir John, this abbey is not what it appears to be.’ Osborne threw off Brokersby’s warning hand.

‘You think these good brothers are united in prayer? Well, look at the facts. The abbot hates the prior who responds with as much loathing. The prior loves the Frenchman Richer with a love not known even towards women. Our Lord Abbot is more concerned about that nasty swan than he is about the rule of St Benedict. He keeps his beloved niece, if that is what she really is, in the guest house guarded by that old harridan. Meanwhile Richer slips in and out of this abbey like a rat from its hole. We’ve seen him wander down to the watergate. Was he there when poor Ailward was murdered?’ Osborne breathed in heavily, wiping the white flecks of foam from his lips on the back of his hand. ‘Then there’s that anchorite, mad as a March hare, in the abbey church, screaming that he is haunted. He has grudges against us, as do Prior Alexander and others who, I am sure, have great sympathy for the Great Community of the Realm and their leaders the Upright Men. Now two of our comrades are foully murdered, certainly not by us. Why not make your enquiries amongst the brothers: Abbot Walter, Prior Alexander, Richer the Frenchman? After all, we’ve seen military service, but they’ve also done their fair share of spilling blood. They can wield swords.’ Osborne’s voice trailed off in a fit of coughing and throat clearing.