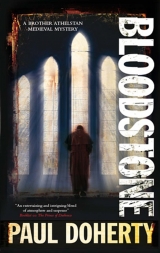

Текст книги "Bloodstone"

Автор книги: Paul Doherty

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

ONE

‘Mummer: an actor wearing a mask!’

‘For my sins, truly I know them,’ Athelstan breathed as he plunged the rough rag back in to the bucket and splashed the herb-drenched water on to the last grey flagstone which lay before the door to his priest house.

‘My sin is always before me,’ Athelstan continued, ‘against you and you alone have I sinned. .’ Once he’d finished washing the flagstone, Athelstan, Dominican friar and parish priest of St Erconwald’s in Southwark, proudly gazed round on what he’d achieved on this the Feast of St Damasus twenty days before the great celebration of the Nativity. He’d cleaned the house thoroughly. He had scrubbed and polished every nook and cranny. The small bed loft was all clean and sweet-smelling, its linen sheets, bolsters and blankets had been changed, and not a pewter dish or copper pot had been missed by him. After that Athelstan had turned his attention to what he mockingly called his solar, the great flagstone kitchen with its whitewashed walls and rough-stone hearth. Everything had been cleaned, from the tongs and pokers in the hearth to the large oaken table which served as both his supper bench and chancery desk.

‘What do you think, Bonaventure?’ Still kneeling Athelstan joined his hands in mock prayer and gazed fondly at the great, one-eyed tom cat sprawling before the crackling hearth like the Grand Cham of Tartary on his gold-encrusted divan. The cat, the prowling scourge of the needle-thin alleyways round St Erconwald’s, deigned to lift his head; he gazed sleepily at his strange master then flopped back as if the effort had proved all too much for him.

‘I know what you are waiting for, my friend.’ Athelstan scrambled to his feet. He emptied the pail of water, wrung out the cloth and walked back into the kitchen. He crouched before the hearth next to Bonaventure and stared hungrily at the blackened copper pot hanging by its chain above the darting flames. He closed his eyes and smelt the warm savouriness of the bubbling oatmeal, hot and sweet with the precious honey Athelstan had stirred in.

‘We’ll eat well, Bonaventure.’ Athelstan stroked the cat’s silky fur. ‘But not yet – God waits.’

Athelstan stripped, shaved, washed then dressed quickly in woollen leggings, drawers and the hair shirt he always wore beneath the black and white robes of a Dominican friar. He buckled the straps of his stout sandals. Going over to a corner he took out the polished dish, a gift from a parishioner, which also served as his mirror. Athelstan stared hard at the face which gazed back at him: the close-cropped black hair, the rather long, serious face with its furrowed cheeks, the wrinkles round both mouth and eyes. Did the face portray the soul, he wondered, or was it just the eyes? In which case Athelstan reflected ruefully, God help him, his eyes were dark and deep set. He practised that hard stare he often used on some of his parishioners.

‘Lord forgive me,’ he prayed, ‘I have to; otherwise they’d lead me an even merrier jig.’

The thought of his parishioners made Athelstan hurry around. He doused the few candles, banked the fire, gazed proudly around his ‘new swept kingdom’ and, grasping his psalter, left the priest house. He secured the door and began what he called his daily pilgrimage. He walked carefully; a hard frost shimmered on the path leading up to the dark mass of St Erconwald’s. All lay quiet. He crossed to the stables, pushed open the half-door and smiled at Philomel, his mount, sprawling on the thick bed of hay Pike the ditcher had so carefully turned the night before. The old war horse lifted his head, neighed and snatched at the fodder net. Athelstan sketched a blessing in the ancient destrier’s direction and continued on. He stopped by the newly refurbished gate to the cemetery, opened it and stepped into God’s Acre. He quietly thanked the Lord for winter because in summer this was a favourite trysting place for his parishioners and others so much so, as Athelstan had wryly remarked to Sir John Cranston, on a midsummer’s day more of the living lay there than the dead. Now it was murky, forbidding and frostbitten. Only a meagre light gleamed from the ancient death house where the keeper of the cemetery, the beggar Godbless, lived with his constant companion, Thaddeus the goat. Athelstan murmured a prayer of thanks for both of them. Young lovers lying down in the long grass of summer were not so troublesome as the warlocks, sorcerers and witches who plagued the cemeteries of London with their midnight rites to summon up the dark lords of the air. The ever-curious, garrulous Godbless, with his equally curious goat, would put any practitioner of such forbidden ceremonies to flight. Godbless, called so because of his constant use of that benediction, would talk them to death whilst the omnivorous Thaddeus would chew any grimoire of spells to shreds.

‘Benedicite,’ Athelstan called out, ‘ Pax et bonum.’

‘God bless you too, Father,’ came the swift reply.

Athelstan passed on up to the church. He fumbled with the key ring, opened the battered corpse door and stepped inside. He wrinkled his nose: despite his best efforts to scrub the floor, the mildewed air of the old church caught his nose and mouth. Athelstan peered through the gloom; the charcoal braziers still glowed like welcome beacons fending off the cold mustiness. Athelstan took out a tinder from the pouch on his cord. He lit the candles paid for by the Brotherhood of Rood Light, a wealthy group of local merchants who used St Erconwald’s as their guild chapel. In return they generously supplied the church with tallow and beeswax tapers. Athelstan lit those in front of the Lady chapel as well as the candles before the statue of St Erconwald. He gazed up at the severe face of the Saxon bishop of London who’d founded the first church here. Huddle the painter had elegantly regilded the statue, delicately picking out the scarlets and whites of the bishop’s vestments. Athelstan, ignoring the scurry of mice in the far corner, lit some of the sconce torches. The friar noticed the tendrils of mist seeping under the corpse door as if they were pursuing him and shivered.

‘God bring us spring soon,’ he murmured, ‘for swarms of bees and beetles bringing in the soft music of the world, for heavy bowls of hazelnuts, sweet apples, plums and whortleberries.’ Athelstan turned to go up into the sanctuary when he glimpsed Huddle’s new painting on the far wall above the leper squint. Athelstan wandered across. Huddle had been busy sketching out in charcoal the Seven Deadly Sins. Athelstan thought the painter would begin with ‘Lust’, which all the parish council wanted. Instead Huddle, who gambled and was desperate for income, had decided on ‘Avarice’. The painting was graphic enough, bold and vigorous, an eye-catching vision of startling colours and images. A goldsmith of Cheapside was Huddle’s incarnation of the deadly sin: a shrivelled up old man, bow-legged and palsy stricken, with a head as bald as a pigeon’s egg, a beard as bushy as a tangle of brier, skimpy loose cheeks, goggling eyes either side of a nose pointed and as sharp as a hook. The goldsmith was being attacked by two shaggy demons that were dragging him away from his money bags. One of these hellish creatures, all hoofed and horned, had wrapped his goatskin legs around the banker and forced his bald head down so as to clamp his wolf fangs into the back of his victim’s exposed neck. The other demon was clawing the goldsmith’s belly, ripping it open to spill out the man’s black and red innards. Gossips, and that was virtually everyone in the parish, claimed Avarice was no less a person than Sir Robert Kilverby, city goldsmith, former alderman and an acquaintance of no less a person than Sir John Cranston, the King’s coroner in London.

‘Sweet Lord, I hope not,’ Athelstan murmured, ‘or Cranston will have Huddle’s head. I just wish our painter would paint and leave the cogged dice alone.’

Athelstan plucked at his waist cord and fingered the three knots symbolizing his vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. Cranston could be genial but, like all law officers in London, watchful and wary of any dissent or mockery of authority. Winter was proving very harsh. The price of bread and other purveyance remained high. Defeat abroad and piracy in the Narrow Seas made matters worse, especially in London where The Upright Men, leaders of the Great Community of the Realm, were plotting bloody revolt to turn the world upside down. Huddle should be careful of whom he mocked. Athelstan went back to the corpse door and picked up his psalter from the stool near the collection of leaning poles. He moved under the rood screen, stood at the bottom of the sanctuary steps and stared up at the Pyx dangling on its chain, shimmering in the glow of the red sanctuary lamp hanging close by. Athelstan genuflected then busied himself, taking out the palliasse from the small alcove where any sanctuary man in flight from the law could settle. Thankfully there was no one. Athelstan unrolled the palliasse at the bottom of the steps just outside the rood screen. He prostrated himself on this, intoned psalm fifty then confessed his sins, a litany of weaknesses: his failure to love, his irritation with Watkin the dung collector, his short temper with Ursula the Pig-woman and her godforsaken sow which followed her everywhere, including into Athelstan’s vegetable patch. The friar caught his temper and smiled. If he was not careful he would be sinning again, yet behind all these petty offences gathered greater shadows: the death of his beloved brother, Francis-Stephen, and his secret love for the widow woman Benedicta, though she was not his only distraction from matters spiritual. Even more so was Athelstan’s fascination for hunting down killers, assassins and murderers who believed they could snuff out another’s life as easily as they might a taper, wipe their lips and, like Pilate, wash their hands of any blood and guilt. Athelstan let his mind drift deeper into the gathering darkness to confront more threatening shapes which questioned his very vocation and basic beliefs.

‘So much evil, Lord.’ He prayed. ‘So deep the wickedness. The rich wax stronger and more powerful whilst the poor, like naked earth worms, are crushed and stamped even deeper into the mud. Why, Lord?’

The friar recalled the words of his own confessor, the venerable Magister Ailred at Blackfriars, the principal Dominican house in London. ‘Evil is not a problem, Athelstan,’ Ailred had advised. ‘If it was a problem, like those we confront in philosophy or logic, it could be resolved. No, Athelstan, evil is a great mystery which can only be confronted. Christ did that during his passion, singing his own hymn of love as he journeyed into the very heart of evil to confront it. He became one of us to experience that same mystery. Look at the crib at Christmas, the Holy Rood on Good Friday. .’ Athelstan sighed, crossed himself and rose to his feet. He wandered down to the main door and stared at the crude but vivid crib set up by Tab the Tinker, Crispin the Carpenter and others. Athelstan smiled. He had imitated the Franciscan idea of the Bethlehem stable and the chanting of the ‘O Antiphons’ instead of the planned mystery play about the Nativity. He’d had a bellyful of that after Watkin, relegated to being one of the shepherds, had furiously assaulted two of the Wise Men. Athelstan sighed noisily and shook his head in admiration of the large gold star Huddle and Crispin had nailed above the crib. He recalled his own secret passion. On a clear night, he’d be up on the church tower observing the stars, but the dire weather froze even birds on the wing whilst threatening clouds blotted out heaven’s gems.

Athelstan doused some of the torches and returned to lie before the rood screen. He intended to recite a psalm but, as usual, he drifted into sleep until roused by a hammering on the locked main door. He struggled awake, pulled himself up, quickly rolled up the palliasse and returned it to the recess. He glanced up at one of the windows and groaned as he noticed the grey dawn light. He had slept too long! The door rattled again. Athelstan hurried down, turned the great key, slipped back the bolts and swung it open. Benedicta, hooded and muffled, and Crim the altar boy almost threw themselves into the church.

‘Sorry, Father, sorry, Father,’ the boy yelped, jumping up and down. ‘It was so cold, we thought we’d die. We wondered what had happened. .’

Athelstan peered behind them at the freezing mist boiling over the great cobbled expanse in front of the church. Night was over and a chilly day had dawned.

‘Day has come,’ Athelstan murmured, ‘and so we must continue our journey.’

‘Father?’

Athelstan smiled over his shoulder at Benedicta. She looked truly beautiful: a simple grey wimple under a cowl framed her olive-skinned face. Benedicta’s lustrous dark eyes, full of life, reminded Athelstan of the frescoes celebrating beauty in the great cathedrals of northern Italy, but now was not the time for reflection on such matters.

‘Never was and never should be,’ Athelstan murmured to himself.

‘What?’ Crim was still jumping up and down, as agitated as a box of frogs.

‘It’s never the time for certain things,’ Athelstan smiled. ‘So come.’

There was, in fact, little time for further conversation or greeting. All three hastened under the rood screen, up the sanctuary steps and into the whitewashed sacristy to the left of the high altar. Athelstan unlocked the vestment chest and the coffer holding the sacred vessels, cloths and bread and wine. Candles were brought out and lit. The sanctuary glowed into light. Manyer the bell clerk, all cowled and visored against the cold, hurried in to sound the bell for the Jesus Mass. The clanging echoed out. At short while later Athelstan’s parishioners, bustling and chattering, coughing and spluttering, filed into the church: Watkin the dung collector; Pike the ditcher with his narrow-eyed wife Imelda constantly on the search for insult; Godbless accompanied by his goat; Ranulf the rat catcher who always brought his two prize ferrets, Ferox and Audax; and Ursula and her sow, the great pig’s flanks and ears all flapping. The sight of so much luscious pork on the hoof, and so vulnerable, made people pause, stare and wet their lips. Basil the blacksmith always sat next to the sow so, as he put it, he could savour its warmth, though many noticed how the blacksmith’s fingers never wandered far from the stabbing dagger in his belt. Moleskin the boatman came along with other members of his coven: Merrylegs the pie-maker, Joscelyn the one-armed former pirate and keeper of ‘The Piebald’ tavern, Mauger the hangman and Pernel the mad Fleming woman who, in anticipation of Christ’s nativity, had dyed her wild tangle of hair red and green.

‘Green for the eternal Christ,’ she had screeched down the nave. ‘Red for his blood.’

They all congregated within the rood screen. Some squatted on the floor; others used the leaning poles. Athelstan, dressed in the purple and gold vestments of Advent, left the sacristy, approached the high altar and made the sign of the cross.

‘I will go unto the altar of God,’ he intoned, and so the Mass began sweeping towards its climax, the consecration and elevation of Christ’s body and blood under the appearance of bread and wine. The singing bread was distributed, the osculum pacis, the kiss of peace, exchanged, the Eucharist given. Athelstan delivered the final blessing.

‘The Mass is finished,’ he declared. ‘Go in peace, but not just yet.’

Athelstan ushered his parishioners out into the nave. He dramatically pointed to the small, self-standing cubicle of oak which stood near the small Galilee porch on the far side of the church.

‘Remember,’ he declared, ‘on one side is a pew for the penitent. On the other, separated by a partition with that lattice grille in the centre, is the seat for the priest.’ He paused. ‘Crispin and Tab built that; it’s our new shriving pew. We must use it. We must all go to confession.’ He smiled at the red, chapped faces of his parishioners, mittened fingers scratching their hair or tugging at ragged cloaks against the cold. ‘I shall be hearing confessions every evening during the last week of Advent to shrive you of your sins.’ His smile widened. ‘I hope to journey to Blackfriars to have my own pardoned.’

‘Do you sin?’ Watkin shouted. ‘You, a friar?’

‘Friars especially,’ Athelstan retorted, ‘then monks and even coroners. By the way, Huddle, I must have a chat with you about your most recent painting. Now,’ Athelstan hurried on, ‘as you know there’ll be no Nativity play. You also know the reason.’

He glimpsed Imelda dig Pike viciously in the ribs.

‘I will not rehearse the sorry reasons why. We took a vote and decided to form our own choir. Now, I have translated the “O Antiphons”.’ Athelstan gestured at the bell clerk, who officiously began to distribute the stained, dog-eared but precious scraps of parchment. ‘I know some of you cannot read.’

‘All of us!’ Tab joked.

‘Perhaps.’ Athelstan clasped his hands. ‘However, we’ve been through the words, we have learnt them. Now let us arrange ourselves in the proper voices.’

The usual confusion ensued but at last Athelstan had his choir ready. The gravel-hard, deep voices of Watkin, Pike and Ranulf at the back, the clear, lucid singers of Benedicta, Crim and Pernel at the front with the others in between. Once he had silence the front line, under Athelstan’s direction, began:

‘Alleluia, Oh Root of Jesse thrusting up, a sign to all the nations.’

The line of singers behind repeated it, and so on. Athelstan caught Benedicta’s eyes and smiled in delight.

‘Wonderful,’ he whispered as he directed them with his hands. These poor but grace-enriched souls sang so strong, so passionately, with all their hearts the great hymn to the Divine Child. Athelstan felt the tears prick his eyes. The antiphons continued.

‘Oh, Morning Star. . Oh, Key of David. .’

When they had finished, Athelstan shook his head in wonderment.

‘All I can do.’ He opened the wallet on his cord and took out a silver coin, a gift from Cranston. He twirled this between his fingers. ‘The labourer, or rather in this case,’ he proclaimed, ‘the singers, deserve their wages. Merrylegs, your pies are baked fresh and piping hot. .?’

Athelstan’s parishioners needed no further encouragement. The coin was snatched and Athelstan had never seen his church empty so swiftly.

‘Was it so good, Father?’

‘Benedicta, even the angels of God must have wept.’ Athelstan walked over and grasped her hands, warm in their black woollen mittens. ‘Benedicta, I am starving. Would you please look after the church and put the vessels back in the fosser?’

With Benedicta’s assurances ringing in his ears, Athelstan left by the corpse door. Bracing himself against the cold, the friar walked back up the lane to the priest house. He opened the door and stared at the huge figure seated on the stool, horn spoon in one hand, crouched over a steaming bowl of oatmeal. Beside Athelstan’s guest, watching every mouthful disappear, was Bonaventure, waiting so when Sir John Cranston, Lord High Coroner of London, finished the bowl he could lick it really clean.

‘Judas,’ Athelstan whispered. ‘Cat, your name is Judas.’ He raised his voice. ‘My Lord Coroner, what is the penalty for stealing a poor friar’s breakfast?’

‘Murder.’ Cranston, wrapped in a Lincoln green war cloak, a brocaded beaver hat of the same colour on his head, turned, his rubicund, white be-whiskered face wreathed in a smile. ‘Murder, my little friar! I have left enough for you then we must go. The sons and daughters of Cain await us.’

‘The eyes of the dark robe of night. The shadow lands which stretch past evensong, these are all part of my story. .’ The enterprising taleteller, perched on an overturned barrel at the end of the lane leading on to the thoroughfare down to London Bridge caught Athelstan’s attention. The friar plucked at Cranston’s arm and paused to catch the dramatic words and colourful images which he hoped to use in a future sermon.

‘There,’ the teller of tales bawled, ‘the larvae of human souls wander whispering like bats twittering in a cave, for this truly is the realm of the screech owl. .’

‘Come on, Friar.’ Cranston, face almost hidden behind his muffler, pointed to where his principal bailiff Flaxwith with his hideous-looking mastiff Samson stood waiting ready to clear a way before the coroner. ‘Come on,’ Cranston repeated, ‘I’ve got a better tale to tell you.’

Athelstan dug into his wallet, dropped a penny into the storyteller’s box and, cowl pulled well over his head, joined Cranston to battle through the surging crowd. Despite a cutting breeze from the river and the stench of uncleared refuse on the slippery paths, London’s citizens had flocked out hacking and sneezing in the freezing air, oblivious to the leaden, brooding clouds which threatened more snow. They hurried down to the tawdry markets around the bridge to gawp, purchase or just gossip. The more vigorous also thronged around the stocks close to the river to fling refuse at Guillaume Lederer, who sat imprisoned for calling Bertram Mitford ‘a covetous snot, a vagabond, a wagwallet’ not to mention, ‘a side-tailed knave’. Guillaume’s name and crime were proclaimed on a placard around his neck, which also invited passing citizens to hurl abuse as well as anything else they could lay their hands on. Further down a more serious business was drawing to an end: the hanging of two women, Dulcea and her companion Katerina, who’d feloniously murdered Alice Willard of Rotherhithe – strangled her, no less, during a pilgrimage to Canterbury. The crowds swirled around the execution cart which abruptly pulled away just as Athelstan and Cranston passed. Both women were left to dance in the air as they slowly strangled on the hempen noose dangling down from the sooty, four-branched scaffold.

Death, of course, especially executions, was good for business and Athelstan was constantly distracted by the charlatans who always emerged on such occasions. One conjurer who, despite it being bleak midwinter, loudly boasted that the small pouch in his right hand contained three bumble bees which he could summon out, one by one each by their own name, as given to him by an angel he’d met on the road outside Havering-atte-Bowe. Other cozeners and conjurers had given up their tricks to plunder the corpses of the hanged and sell their ill-gotten items for a profit. A few of these knights of the dark just hoped the macabre scenes would influence the minds of those they hoped to cheat. Outside the Chapel of St Mary Overy a journeyman, his black capuchon, cotehardie and chausses embroidered with gold stars and silver moons, proclaimed how he, John Crok of Tedworth, had in the scarlet-blue fosser beside him a man’s head in a book. He proclaimed how the head was that of a Saracen. How he had bought it in Toledo in order to enclose a certain spirit which could answer questions about the future. Apparently the said spirit had not informed him about the approach of the coroner. One look at the burly Flaxwith and the equally fearsome Samson sent John Crok of Tedworth, his precious fosser clutched under one arm, fleeing through the crowds. Cranston just grunted noisily and muttered about some other time.

They passed under the gatehouse to the bridge, its crenellations ornamented with long poles bearing the severed heads of executed traitors, pirates and other criminals. On the steps leading up to the gatehouse sat the diminutive Robert Burdon, the keeper surrounded by his brood of children. Burdon was preparing another head, all pickled and tarred, to decorate the end of a pole. He glimpsed Cranston and Athelstan, shouted a greeting and continued with his macabre task of combing the long hair on the severed head.

Athelstan was now finding it difficult to keep up with Cranston’s stride. He still wasn’t sure where they were going or what they were doing. Cranston had told him little except that his wife, the diminutive Lady Maude, and their two sons the poppets were all ‘in fine fettle’. Then he added something, just as they left the priest house, about the mysterious death of Kilverby the Cheapside merchant as well as the gruesome slaying of one Gilbert Hanep at the great Benedictine Abbey of St Fulcher-on-Thames. The coroner also mentioned John of Gaunt, a precious bloodstone called the ‘Passio Christi – the Passion of Christ’ and that was it. Athelstan was curious for more but decided he would have to wait, especially here on London Bridge with its crowded shops, booths and stalls. The houses packed on either side soared up against the grey sky, forcing them and others to push up the broad narrow lane between, already packed with carts rattling on iron-bound wheels, braying sumpter ponies and apprentices bawling, ‘What do ye lack, what do ye lack?’ The sheer crush, the rancid stench of unwashed bodies, the clatter of waterwheels and the pounding of the angry river against the starlings of the bridge were a stark contrast to the silence Athelstan was accustomed to. He felt slightly dizzy as if he’d not eaten, even though he had. Cranston, thankfully, had not devoured all the oatmeal. Athelstan crossed himself and murmured the ‘ Veni Creator Spiritus’. He certainly needed God’s help. He was about to enter the meadows of murder, creep along the twisted alleyways along which padded the silent, soft-footed assassin. The age old duel was about to begin; as always, it would be ‘ lutte à l’ outrance, usque ad mortem– a fight to the death’. Would it be his? Athelstan wondered. Would he draw too close, make a mistake?

Athelstan touched Cranston’s arm for comfort; the coroner pressed his hand reassuringly and they left the bridge, entering the wealthy part of the city. The streets, paths and alleyways here were packed with fatter, fuller bodies encased in gaily caparisoned houppelandes, capuchons, cloaks, poltocks and tabards. Merchants, shimmering in their jewellery pompously paraded, accompanied by wives bedecked in gorgeous clothes and elaborately decorated headdresses. Knights in half-armour on plump, powerful destriers trotted by. Lawyers, resplendent in red silks, hastened down to the ‘ Si Quis’ door at St Paul’s. The stalls and booths were open and business was brisk. Merchants and traders offered silver tasselled dorsers and thick woollen cushions for benches. Priests and monks, armed with cross and thuribles, processed to this ritual or that. The air was rich with the many smells from the public bakehouse as well as the fragrance of the vegetable stalls stacked high with onions, leeks, cabbages and garlic. Next to these the fleshers’ booths offered suckling pigs and capons freshly slaughtered and drained of blood. Pilgrims to the shrine of Becket’s parents rubbed shoulders with those fingering pardon beads as the Fraternity of the Salve Regina made their way down to one of the city churches.

Squalor and brutality also made themselves felt. Beggars, covered in sores and garbed in rags, clustered at the mouth of alleyways and the spindle-thin runnels which cut between the mansions and shops. Outside the churches the poor swarmed, desperate for the Marymeat and Marybread given out by the parish beadles in honour of the Virgin. Fripperers pushed their handcarts full of old clothes, ever quick to escape the sharp eyes of the market bailiffs. A clerk, who’d begged after hiding his tonsure with cattle dung, was being fastened in the stocks, next to him a woman who’d stolen a baby so she could plead for alms. The noise, bustle, smell and colour deafened the ear and blurred the mind. The forest of steepled churches continuously clanged, their bells marking the hour for Mass or another recitation of the divine office. Smoke, fumes and smells from smithies, cook shops, tanneries, fullers, taverns and alehouses mingled and merged. Dung carts crashed by, full of ordure collected from the streets. Night-walkers, faces the colour of box-wood, were being marched, manacled together, to stand in the cage on the Tun in Cheapside. Children, dogs and cats raced through gaps in the crowds, spreading their own noise and confusion and drowning the shouts of tinkers and traders.

Athelstan, who’d taken to fingering his Ave beads, sighed with relief when Flaxwith, Samson trotting behind him, abruptly turned into Rosenip Lane, leaning towards the great mansions of Cheapside. Each of these stood behind its own towering curtain wall, their rims protected by shards of pottery and broken glass. The noise, stench and clatter died away. They stopped before one mansion. A porter let them through the smartly painted black gates and into the broad gardens where small square plots of herbs, shrubs and plants lay dormant in the severe grip of winter. Athelstan gazed around. There were clumps of apple and other fruit trees, their branches stark black whilst the large stew pond was nothing more than a thick sheet of ice. Athelstan hurried to keep up with Cranston as he strode along the white-pebbled path leading towards an enclosed porch built around the main door.

A grey-haired, grey-faced, grey-eyed servant, who introduced himself as Crispin, Sir Robert Kilverby’s secretarius or clerk, ushered them in. Athelstan had been struck by the gorgeous wealth of this red-brick mansion with its blue slated roof, glass-filled windows and soaring chimney stacks. The interior was no different. Athelstan and Cranston walked across tiled floors of black and white lozenges. Drapes and tapestries decorated the pink-washed plaster above gleaming wooden panelling. A gorgeous riot of colours: emeralds, deep blues, argents, purples and gleaming reds pleased the eye. Beeswax tapers glowed on spigots and candelabra, shimmering in the sheen of oaken sideboards boasting gold and silver gilt cups, mazers, dishes and goblets. Thick turkey cloths covered some floors whilst heraldic devices decorated the walls of the broad staircase they climbed. The air was fragrant with the smell of scented woodsmoke as well as the perfumes from small heated herb pots pushed into corners or on sills, a pleasing mixture of black poplar, green grape and elder oil. Nevertheless, Athelstan detected a tension, a watching silence beneath all this opulence.