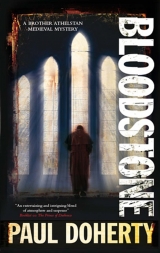

Текст книги "Bloodstone"

Автор книги: Paul Doherty

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

Richer simply spread his hands, Prior Alexander slipped further down his chair.

‘There’s no “Liber”, no copy,’ Richer muttered.

‘I might insist on searching this abbey, including your chamber, Richer.’

‘You can’t. .’

‘We can and we might,’ Cranston retorted.

‘The Passio Christi,’ Athelstan asked, ‘do any of you know where the bloodstone is?’

‘No,’ Richer’s voice was restrained, ‘I swear, no!’

‘The Passio Christi,’ Athelstan got to his feet, ‘and the book about it hold the key to all this mystery, and the question which lies at the very heart of it: why did Sir Robert change so radically? There was more to that than his own scruples or your eloquence, Richer.’

‘I cannot help you on that!’

‘Never mind.’ Cranston rose and stood over the Frenchman. ‘You, Brother, whoever you may be, are confined to this abbey. Any attempt to flee will be construed as a treasonous act.’

‘I’m a Frenchman.’

‘And His Grace, King Richard,’ Cranston thrust his face down, ‘also claims to be King of France. Richer, you are confined to this abbey under pain of treason. Brother Athelstan?’

The coroner and friar stepped out of the chamber. Once they’d left the courtyard Athelstan paused.

‘Perhaps we should begin now, Sir John.’

‘Begin what?’

‘Our search!’

Cranston agreed. He and Athelstan adjourned to the library. Richer joined them. Athelstan told him to stand aside, yet even as they searched Athelstan realized they would find nothing amongst this precious collection of books. Richer was cunning. Should they, Athelstan wondered, demand that the sub-prior’s chamber also be searched? But, there again, the Frenchman was now alert to the danger. Moreover, although the ‘ Liber Passionis Christi’ might prove very useful, its disappearance did not prove Richer, or anyone else, to be an assassin or a thief. Athelstan sighed as he placed the last book, a copy of Lucretius, back on the shelf.

‘Sir John, I’m ready!’ The firedrake in all his garish glory marched into the library. Cranston smiled at Athelstan and both followed this eccentric character out through the cloisters to Mortival meadow where the abbey chandler waited.

‘I’ve everything prepared.’

The firedrake pointed to a barrel with a capped tallow candle on its upturned end. The firedrake struck a tinder, sheltering its flame against the boisterous cold breeze. The wick flared into life. The firedrake hastily withdrew. The tongue of flame danced even though it was protected by the concave-shaped cap. Cranston stamped his feet impatiently; almost in response the candle dissolved in a burst of angry, spitting flames. Small tongues of fire shot up to land, hissing like snakes on the frost-hardened grass. The top of the dry wooden barrel caught light, flames licked down its side already smouldering from the spits of fire. Soon the entire barrel was alight. Athelstan thought the flames would die but then a fresh burst flared up, angry shoots of fire leaping so swift and fierce the entire barrel was soon reduced to blackened wood crumbling away in fiery fragments.

‘You see.’ The firedrake was almost dancing with glee whilst the abbey chandler beamed at the dying fire. The monk abruptly remembered what he was doing and hurriedly pulled a more mournful face. ‘That’s how Brokersby died,’ the firedrake declared.

‘Do explain,’ Cranston insisted.

Athelstan sniffed the grey-black smoke and walked closer to the dying fire. The tang of oil was strong, needle-thin rivulets of smoking blackness scored the frozen grass.

‘Very simple.’ The firedrake breathed in the smoke as if it was the very incense of heaven.

‘Then keep it so,’ Cranston retorted, ‘and brief. I’m freezing.’

‘Come, come,’ the chandler insisted on taking them back to his own work shop, a large chamber which reeked of oil, cordage and wax. He made them sit on stools around a brazier which sparkled just like a ruby. Athelstan, clutching the cup of posset the chandler served, ruefully wondered on the whereabouts of the bloodstone.

‘Very simple.’ The firedrake held up a large tallow candle. He turned this upside down tapping its base. ‘You hollow this out and pour in oil, perhaps add some salt-petre powder, the type used by the King’s newfangled cannons – you’ve seen them at the Tower?’

Cranston grunted.

‘Reseal the candle with a wax plug and you have nothing less than a vase of oil.’

‘If you light the wick,’ Athelstan agreed, ‘the flame burns down, the wax dissolves and the conflagration begins. The lower the oil sits in the hollowed-out candle, the longer it takes.’

‘I’ve seen it done,’ the chandler observed ruefully. ‘Sir John, as coroner, you must have encountered tallow-makers, candle-fashioners who use cheap materials within a shell of wax?’

‘I have,’ Cranston drank from his posset cup, ‘which explains why the guild’s regulations are so stringent against such a practice.’

‘That and more,’ the firedrake explained. ‘This barrel was as dry as tinder. Inside it was a small pouch of oil. The false candle was perilous enough but the oil would make it truly dangerous. You must have seen conflagrations; people forget how fast flames can move. I’ve seen fires in dried forests course swifter than a fleeing deer. Burning oil is even worse.’ He waggled a finger. ‘Very dangerous – it turned our candle into a fountain of spitting flame.’

‘So,’ Athelstan drained his cup, ‘somebody entered Brokersby’s chamber. They placed a wine skin, one full of oil sprinkled with salt-petre, under his bed. The tallow candle was replaced with a false one. Brokersby either lit it or let it burn as he was accustomed to. He retired to bed, his belly full of wine, an opiate, or both. The candle eventually disintegrated in a shower of flame which would swiftly reach the pouch of oil hidden away.’ Athelstan crossed himself. ‘The bed was of dry wood, linen sheets and woollen blankets, ideal fuel. Brokersby may have woken and tried to stagger out of danger but the fire was all around him. The oil-rich flames would have turned him into a living torch. My friends,’ Athelstan rose and bowed, ‘I thank you heartily but your hypothesis leaves one tantalizing question.’ He stared down at them. ‘Why? Why kill any soul but especially why like that, the artifice, the subtle cunning, why?’

Cranston escorted the firedrake, rewarded with good silver, back to the watergate. Athelstan took to wandering the abbey. He felt agitated. The buildings seemed to crowd in around him. The statues and carvings appeared to draw closer, making him more aware of sightless eyes, stone smiles and frozen glances. He became acutely alert to the dappled light, the black alleyways and the yawning mouths of corridors. Bells tolled. Monks slipped here and there on different duties. Athelstan sensed a change: their mood was colder, more distant. Bony white faces peered suspiciously out at him from hoods and cowls. Brothers turned and whispered to each other as he passed. Athelstan entered the church to pray before the lady altar. Afterwards he went and stood before the anker house but the anchorite was either asleep or pretended to be. Athelstan returned to his own chamber and tried to clear the fog of mystery behind the disappearance of the bloodstone and these horrid murders. Were they all connected? Athelstan wondered. Or should he look at Kilverby’s murder as separate from the rest? The Passio Christi did link Kilverby to the Wyvern Company. Another tie was Richer. Athelstan curbed his frustration. Ideally, Cranston should seize the Frenchman and hoist him off to the Tower for closer questioning. Richer however was a cleric, a monk. He would plead benefit of clergy and, within the day, every churchman in London would be stridently protesting.

SEVEN

‘Placitum: a case heard before a court.’

Next morning, after a troubled sleep, Athelstan celebrated a late Mass. As he divested he wondered if he should escape the abbey and return to St Erconwald’s for the day. Outside in the aisle the brothers were preparing their own crib, bringing in lifelike statues and arguing about whether the abbot wanted the Three Kings immediately or should they wait until the Epiphany. Athelstan was about to help when he glimpsed an inscription carved along the rim of the chantry altar. He swiftly translated the Latin. He was about to close his eyes in thankful prayer when he heard his name being called. Prior Alexander, unshaven and red-eyed, his black robe stained and blotched, pushed through the gossiping brothers to inform Athelstan that Cranston required him urgently near the watergate. Athelstan collected his cloak and writing tray and hurried down across Mortival meadow, pleasantly surprised by the change in the weather. The mist had lifted. The clouds were thinning and the weak sunlight gave the meadow a more springlike look. On the quayside Cranston, cloaked, booted and armed, stood with Wenlock and Mahant, similarly attired. The old soldiers looked heavy-eyed as if roused from an ale-sodden sleep. Moored along the quayside was a high-prowed barge with a covered awning in the stern. The prow boasted a snapping pennant of dark blue fringed with gold displaying the insignia of the Fisher of Men, a silver corpse rising from a golden sea. The barge was manned by six oarsmen dressed in black and gold livery – these were the Fisher of Men’s coven, outlaws and outcasts who’d rejected their own names and rejoiced in being called Maggot, Taffyhead, Badger, Brick-face, Gigglebrazen and Hackum. Standing on the barge was Icthus, the Fisher’s principal assistant, dressed in a simple black tunic, a strange creature who took the Greek name for fish, an apt enough title. The young man had no hair even on his brows or eyelids whilst his oval-shaped face and protuberant cod mouth made him look even more like a fish. Icthus raised a hand in greeting as Cranston broke off whispering heatedly with Wenlock and Mahant.

‘Osborne’s been found,’ Cranston declared, ‘or at least his corpse, naked as he was born, throat slit from ear to ear.’ Cranston waved at the waiting barge. ‘The Fisher of Men requires an audience. Wenlock and Mahant are coming with us whether they like it or not.’

They all clambered into the barge. Icthus in a high-pitched voice ordered the oarsmen to push away and soon they were out, the rowers bending and pulling back in unison. The river was thankfully calm though busy with fishing smacks, bum boats and market barges all taking advantage of the break in the weather. Mahant and Wenlock sat fascinated by Icthus and his companions. Cranston tersely explained how the Fisher of Men was a retainer of the mayor and city council. The Fisher’s task was to roam the Thames and drag out the corpses, the victims of suicide, murder, or accident.

‘A common enough occurrence,’ Cranston confirmed. ‘He,’ the coroner pointed at Icthus, who sat with his back to them crooning a song to the rowers, ‘has one God-given gift: he can swim like an fish whatever the mood of the river.’

‘Where was Osborne found?’ Wenlock asked.

‘Down river,’ Cranston remarked, ‘trapped amongst some reeds. Icthus believes he was thrown in somewhere between the abbey and La Reole.’

‘We have his assurance it’s Osborne?’ Wenlock shifted his gaze from Icthus to Cranston.

‘We shall see,’ the coroner replied. ‘Apparently not only was the victim’s throat slashed but someone used a hammer, or a rock, to pound his face into a soggy mess of blood, bone and tattered flesh.’

‘Sweet Lord,’ Mahant whispered, sitting squashed in the semicircular stern seat, he leaned down and gently touched the hilt of his sword for comfort.

Cranston nudged Athelstan and pointed to a flock of birds which seemed to cover the corpse dangling from a crude gallows on a sandbank.

‘That reminds me – Leda the swan. Do you really think the Upright Men hanged that poor bird?’

Athelstan recalled what he’d glimpsed in the chantry chapel that morning.

‘Leda was hanged,’ he replied evasively, ‘by someone with a deep hatred for my Lord Abbot.’

‘That must include,’ Wenlock declared, ‘virtually most of his community and everyone outside it.’

Athelstan, reluctant to continue the conversation, stared round the awning at the other barges passing close as they moved in towards the quayside. Athelstan studied them and glimpsed Crispin, Kilverby’s secretarius, sitting huddled in the centre of one skiff staring directly at the Fisher of Men’s barge. Athelstan swiftly drew back. Crispin was apparently heading for St Fulcher’s. Athelstan wondered what urgent business brought him back to the abbey? Icthus, in that eerie voice, abruptly called out commands. The barge rocked as it turned and came alongside a deserted wharf just past La Reole. They disembarked and made their way up to what was variously called, ‘The Barque of St Peter’, ‘The Chapel of the Drowned Man’ or ‘The Mortuary of the Sea’, a single storey building of grey brick with a red tiled roof. The corporation had built this so all the corpses harvested from the Thames could be laid out for inspection and collection by relatives; if not recognized, they were placed on to the great cart standing alongside the Barque and taken to some Poor Man’s Lot in one of the city cemeteries.

The mortuary fronted the quayside, on either side ranged the wattle and daub cottages of the Fisher of Men and what he termed ‘his beloved disciples’; others called them ‘the grotesques’. Athelstan stared up at the vigorously carved tympanum above the wooden porch showing the dead rising from choppy waves to be greeted by the angels of God or the demons of Hell. Beneath this ran the words: ‘And the Sea shall give up its dead’. On the right side of the door hung the great net which the Fisher of Men used to bring in the bodies, above it another inscription: ‘The deep shall be harvested’. On the left side of the door a proclamation boldly proclaimed the prices for recovering a corpse. ‘The mad and insane – 6p. Suicides – 10p. Accidents – 8p. Those fleeing from the law – 14p. Animals – 2p. Goods to the value of £5: ten shillings. Goods over the value of £5, one third of their market value’. The Fisher of Men was seated beneath the sign, his bald head and cadaverous face protected by a leather cowl edged with costly fur. A thick military cloak shrouded his body from head to feet, which were pushed into the finest cordovan riding boots. The Fisher of Men rose and greeted his visitors in fluent Norman French and, turning specifically to Athelstan, lapsed into Latin. He asked the friar if he would give him and his ‘beloved disciples’ a formal blessing before leading them in their favourite hymn, ‘ Ave Maris Stella– Hail Star of the Sea’.

Athelstan, as always, was tempted to ask the Fisher about his past, his knowledge of Latin and the classics. Cranston, however, had warned Athelstan how this harvester of corpses was most reluctant to reveal any aspect of his past, be it stories about once being a leper knight or a merchant who had visited the court of the Great Cham of Tartary.

‘Well, Brother?’

‘Of course, of course.’

The Fisher of Men turned to Icthus, who produced a hunting horn and blew a long haunting blast which hastily summoned the members of that strange community to kneel on the cobbles before ‘The Barque of St Peter’. With Cranston and the others looking on, Athelstan delivered the blessing of St Francis.

‘May the Lord bless you and protect you.

May he show you his face and smile on you.

May the Lord turn his face to thee and give you peace.

May the Lord bless you.’

When Athelstan finished he sketched a cross in the air and intoned the ‘ Ave Maris Stella’, the rest of his singular congregation merrily joining in, chanting the Latin hymn learnt by rote to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Once the ‘Amen’ had been sung, the Fisher of Men clapped Athelstan’s shoulder and led him and the others into the Sanctuary of Souls, a rectangular lime-washed chamber. On a dais at the far end stood an altar draped with a purple and gold cloth, above it a large crucifix nailed to the wall. The Fisher’s ‘guests’, as he described the corpses plucked from the Thames, were placed on wooden trestles, each covered with a shroud drenched in pine juice. The stench, despite the herbs, was sharp and pungent, a sombre place of haunting sadness. Athelstan blessed the room even as Icthus and two of his companions came around him swinging thuribles, anointing the air with sweet smoke. The Fisher removed the shroud covering one corpse. Athelstan immediately gagged at the sight and grasped the proffered pomander. Cranston and the two soldiers cursed until the Fisher of Men loudly tutted. The face of the corpse, already bloated liverish by the river, had been reduced to a reddish-black pulp, the nose and lips fragmented into a grotesque mask. The body was naked, the muscular torso, legs and arms streaked with old wounds. Athelstan stared closely; he could not be certain who it was.

‘Osborne,’ Wenlock murmured. ‘It’s Osborne.’ He turned to the Fisher of Men. ‘How did you know?’

The Fisher lifted the arms of the corpse, he pointed to the wrists marked by the bracers now removed and the deep calluses on the arrow fingers of the left hand.

‘We keep our eyes and ears sharp. We read and learnt the description Sir John posted at St Paul’s Cross and elsewhere. How you were seeking Henry Osborne, former master bowman, who fled without permission from the Abbey of St Fulcher. Where would such a man flee, we asked? We heard about the deaths at the abbey so when Icthus fished this corpse from the reeds, throat cut, face all disfigured, corpse stripped, we wondered. I examined the wrists, which the archer braces would usually cover, the fingers worn by years notching a bow. .’

‘Where did you find him?’ Cranston indicated for the cadaver to be covered.

Athelstan didn’t wait for the answer; he took a deep breath on the pomander and walked back to the door. He glanced over his shoulder. Wenlock and Mahant stood apart, hiding in the murky light of that grim place. Cranston was helping with the funeral cloth whilst the Fisher of Men and his acolytes gathered around all pleased, eager for their reward.

‘God forgive me,’ Athelstan murmured, ‘for my lack of thought.’ Clutching his writing satchel, he walked back to the trestle. He took out the small phials of holy oils and insisted on anointing the corpse whilst he whispered the words of absolution. He tried to ignore the brutal remains which once housed a living soul, concentrating on the rite whilst the bile bubbled at the back of his throat. Once finished he gratefully strolled outside to the fiery heat from a huge brazier where the rest were already warming themselves. Wenlock and Mahant, now vociferous, informed Cranston how they no longer wished to reside at St Fulcher’s. Cranston warned them that, until he was finished, they could either stay there or be lodged in the Tower and that applied to anyone else involved in these dire events.

‘You must also surely,’ Athelstan added tactfully, ‘see to the burial of poor Osborne? He should be interred next to his comrades at St Fulcher’s?’

The two old soldiers, hands extended over the glowing coals, just glared back at him.

‘You, Magister.’ Athelstan turned to the Fisher of Men. ‘How long do you think Osborne’s corpse was in the water?’

‘He was discovered just after first light,’ that gleaner of the dead replied, ‘in a reed bed. We think he must have been there for at least a day. More importantly, we know where he came from.’ This stilled all conversation.

‘Osborne was murdered,’ the Fisher of Men declared stoutly, ‘on Sunday evening. The weather is too cold even for an old soldier to camp out. In addition, if you know the flow and pull of the river you can deduce where his body fell in.’ He rubbed his hands together.

‘Where?’ Wenlock snapped. ‘Let’s not play games.’

‘My friend, I am not! Listen, Osborne needed shelter. The only place providing that between here and St Fulcher’s is the great riverside tavern, “The Prospect of Heaven”.’

Cranston nodded in agreement.

‘After we found the corpse I sent one of my best scurriers, Hoghedge, who has a nose for tap room gossip. Minehost at the “Prospect” clearly remembered an old soldier armed, carrying his bow not to mention a fardel and panniers, who hired a chamber very early on Sunday morning. He called himself Brokersby.’

‘Brokersby?’

‘That’s what he called himself. Anyway, Minehost recognized an old soldier when he saw one. His guest kept to himself then, later that Sunday, this individual settled all accounts, took his baggage and walked down the towpath towards the river.’

‘And?’

The Fisher clicked his tongue noisily.

‘That is all I can tell you.’

‘Osborne left St Fulcher’s.’ Athelstan turned to the dead man’s companions. ‘He sheltered at that tavern under the name of Brokersby for most of the day then left. Can you tell us why?’

Both men just shook their heads.

‘He did not contact you?’

‘Of course not,’ Wenlock retorted. ‘Nor do we know why he’d go there. We thought he’d hide deep in the city.’

‘Did you find any of his possessions?’ Wenlock turned to the Fisher of Men who just waved back at the Sanctuary of Lost Souls.

‘Naked we come into the world,’ that strange individual intoned, ‘and naked we shall surely leave.’ The Fisher smiled at the coroner. ‘Sir John, if there’s nothing else?’

Cranston and the Fisher of Men walked away from the rest, disappearing into one of the cottages. A short while later Cranston emerged carrying a scrap of parchment, a receipt for the exchequer to account for the monies he had paid to the Fisher of Men. Cranston, Athelstan and the rest clambered back into the barge and, with the cries of farewell from that bizarre community ringing out over the water, the ‘Charon of Hades’ as the barge was called, took them back along the river. Cranston however insisted that they stay close to the bank and pull into the narrow quayside close to ‘The Prospect of Heaven’. He asked them to wait, swiftly disembarked and strode off up the towpath towards ‘The Prospect’; its great timbered upper storeys and black slate roof could be clearly glimpsed from the barge. Wenlock and Mahant followed and, cloaks wrapped about them, walked up and down, whispering between themselves as they tried to keep warm. Athelstan studied both of these. The two old soldiers were unusually taciturn and withdrawn. Were they fearful, anxious? He tried to catch the essence of their mood, their souls. Would they also flee? But, there again, Osborne really hadn’t. He’d simply assumed his dead comrade’s name and moved a short distance down the river. Athelstan took out his Ave beads and fingered them. ‘The Prospect’ was an ideal place to hide. A ramshackle sprawling tavern along the Thames where merchants, travellers, pilgrims and river folk ebbed and flowed like the water itself. So, why had Osborne really left St Fulcher’s? What was he doing at that tavern? Why had he left? How had he been so swiftly overcome, his throat slashed, his corpse stripped of everything, his face pounded beyond recognition before being tossed like rubbish into the river?

Athelstan turned as Icthus and his oarsmen broke off from the hymn they were softly chanting and pointed excitedly as the war cog, its prow and stern richly gilded, sails billowing, the armour and weapons of its crew twinkling in the light, rounded a bend in the river. The cog, ‘The Glory of Lancaster’, was surrounded by small boats eager to sell provisions and even the joys of some whores gaudily bedecked and crammed into a skiff by an enterprising pimp. The sight of the cog made Athelstan think of Richer. Was the Frenchman responsible for Osborne’s death? Richer with his many emissaries from foreign ships? Had Richer persuaded Osborne to flee with a promise of safe passage abroad then killed him, but why? Was it to do with the truth behind the theft of the Passio Christi or even where it was now?

‘Nothing!’ Cranston almost jumped into the barge, hastily followed by Wenlock and Mahant.

‘Nothing at all.’ Cranston squeezed into the seat. ‘It’s as the Fisher of Men said. God save us, Athelstan, I tell you this.’ He raised his voice. ‘Osborne will be the last person to flee.’

On their return to St Fulcher’s Athelstan discovered the reason behind Cranston’s statement. The coroner had been busy and his messages into the city had borne fruit. The watergate and every entrance into the abbey were now guarded by royal archers, men-at-arms and mounted hobelars. The same, Cranston declared as he strode across Mortival meadow, patrolled the fields and woods beyond the abbey walls whilst the cog they’d glimpsed had taken up position off the abbey quayside.

‘There will be no more secret meetings, leaving or goings,’ Cranston insisted as they reached the guest house. ‘Everyone, and I mean everyone, will stay where they are.’ The coroner’s edict was soon felt. Cranston relaxed it a little, allowing carts of produce, visitors, beggars and pilgrims, as well as individual monks, to come and go but the royal serjeants had their orders. Everything and everyone were thoroughly searched. The protests mounted. Wenlock and Mahant tried to leave claiming they hoped to secure lodgings in the city along Poultry. Cranston refused them permission. Abbot Walter, still shocked and surprised at the truths he’d had to face as well as the death of his beloved Leda, retreated to his own chamber with his mistress and daughter. Prior Alexander and Richer, however, were furious. They both confronted Cranston and Athelstan as they broke their fast in the buttery. The two monks were joined by Crispin, who bleated he should journey back to the city, claiming he had urgent business with Genoese bankers in Lombard Street. Cranston heard them out, cleared his throat and ordered all three to shut up and listen.

‘You,’ he pointed with his finger, ‘all of you are suspects in this matter.’

‘How dare you?’ Richer’s handsome face reddened with rage. He fidgeted with the hilt of the silver dagger in its embroidered sheath on the cord around his waist.

‘Oh, I dare,’ Cranston replied evenly, ‘that’s the problem, my friends. This abbey is like a maze of alleyways. People scurry about bent on any mischief, even monks who go armed.’

‘I am fearful,’ Richer retorted, ‘the Wyverns hate me. Men are being murdered.’

‘Which is why you are all suspects?’ Athelstan smiled. ‘Anyone associated with Sir Robert, the Passio Christi or the Wyvern Company must hold themselves ready for questioning either here or the Tower. That includes you, Master Crispin. I would like you to stay here at least for a day.’

‘Why?’ the clerk protested.

‘Because I am determined to finish these matters,’ Athelstan declared. ‘Don’t worry, this applies to everyone else. Sir John, I am sure, has issued instructions that all members of Sir Robert’s household be confined to their mansion.’

‘Are you so close to the truth?’ Prior Alexander asked.

‘Very close – we always were,’ Athelstan retorted. ‘We are just frustrated by lies and evasions and that includes you again, Master Crispin. You knew full well that Sir Robert was spending lavishly, bribing the monks of St Fulcher to send back treasures to St Calliste, and that you and Sir Robert were once novices here. That Sir Robert was not going on pilgrimage but fleeing. I am sure all his accounts are in order.’

‘I don’t. .’

‘Please don’t lie,’ Athelstan warned. ‘Sir Robert was not coming back. He did not intend to leave the Passio Christi here but take it back to St Calliste himself, or so I suspect.’ Athelstan brought the flat of his hand down loudly on the table. ‘So yes, we may be close to the truth, though gaps remain. Consequently you will all stay here until we finish. Now, sirs, we would like to finish our meal. However, before I do, one last question, Master Crispin: what are you actually doing here?’ Athelstan jabbed a finger at him. ‘Again, no lies. You came to find out what was happening?’

Crispin nodded. ‘True,’ he sighed, ‘the mansion in Cheapside is now surrounded by archers. I had to discover what was going on.’

‘Now you have,’ Athelstan replied. ‘So, all of you, please go.’

‘Are we close to the truth?’ Cranston asked once their visitors had left.

‘Yes and no, my Lord Coroner. Yes in the sense that we have the keys but we don’t know which keys fit which locks. We are now dependant on time and three other factors: first, and I must reflect on this, a vigorous search of this abbey, including Richer’s chamber, might be of use. Secondly, matters proceed apace. Another bloodletting might take place and the killer might make a mistake.’

‘And the third?’

Athelstan took a deep breath. ‘God also demands justice. I pray he gives it a helping hand.’

Athelstan returned to his chamber whilst Cranston decided to visit the serjeants in change of the royal archers. The friar locked himself away listing time and again all he knew. He found it difficult to make any progress on the bloody affray here in the abbey except on two matters. First, when Hyde was murdered near the watergate, Richer ran back to see what had happened. Driven by his deep hatred for the Wyvern Company, the Frenchman thrust his sword deep into Hyde’s belly but. . Athelstan paced up and down. Surely Richer must have glimpsed the assassin who’d fled, certainly not through the watergate where Richer and the boatman were doing business, but across Mortival meadow, even if it was to hide in one of the copses? If the assassin had been one of the Wyvern Company, Richer would have been only too pleased to point the finger of accusation, so was it someone else? Someone he recognized? A monk from this abbey? Prior Alexander? Secondly, Athelstan could not forget the attack on him in the charnel house, the speed with which his assailant had opened the door and doused those sconce torches. As regards to Kilverby’s death and the disappearance of the Passio Christi? What if Kilverby himself had removed the Passio Christi, locked the coffer and put the keys back around his neck knowing full well the Passio Christi was safe elsewhere? Athelstan could make no sense of this so he returned to listing his questions, trying to construct a hypothesis which he could push to a logical conclusion. Frustration, however, got the better of him. Athelstan visited the church to pray and, when Cranston returned, listed his unresolved questions for the coroner.