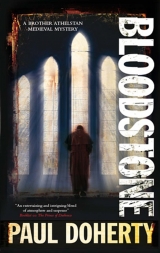

Текст книги "Bloodstone"

Автор книги: Paul Doherty

Жанр:

Исторические детективы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 12 (всего у книги 17 страниц)

SIX

‘Hoodman blind: blindman’s bluff.’

Athelstan found his parishioners well away from the abbey. They had seen the glories of the church and were full of stories about the strange anchorite who’d swept by them like some baleful cloud to hide himself in his anker house. They had all supped well in the refectory on fish stuffed with almonds, lentil soup, rich beef stew, blancmange, sweet cakes and as many blackjacks of ale as they could down. Now, rosy cheeked with merriment, they had gathered around the new hog enclosure to stare at the abbey’s herd of fierce, snouting pigs with hairy, bristling ears and greedy maws. Powerful animals with quivering flanks and muscular legs, the hogs had turned their great enclosure and the surrounding stys into a reeking quagmire of cold, hard mud and steaming droppings. The hogs, aroused by the noise and chatter, crashed into the sturdy stockade much to the enjoyment of Athelstan’s parishioners who relished it, as Watkin slurred, better than any bear baiting. Athelstan, wary of these ferocious beasts, coaxed his little flock back up into the church. Cloaks were put back on, only to be taken off as Pike the ditcher announced he wished to personally inspect the abbey latrines.

At last, as the shadows crept from the corners, order was imposed. Athelstan lined them up. He glimpsed the bulging pockets in cloaks and gowns and guiltily realized that his parishioners had probably left little in the refectory and that included tankards, platters and anything else which moved. He led them down to the darkening quayside and, having given them parting words of advice, delivered what he called his most solemn blessing. He sadly watched the two barges manned by Moleskin and his comrades disappear into the mist, the good wishes of his parishioners carrying eerily towards him. Athelstan turned and walked back to where Cranston stood waiting for him by the watergate.

‘Very well,’ Athelstan breathed, ‘let us return to my chamber. I suggest you take the one next to it. We’ll have something to sup. Let the bells of the abbey clang for divine office. Sir John, God has more pressing work for us. He wants us to search out the children of Cain and bring them before the bar of his justice.’ Athelstan escorted Cranston to the buttery then back to his warm chamber. He bolted the door, prepared his writing tray and stared at his portly friend now sitting bootless on the edge of the bed.

‘Item:’ Athelstan began, ‘The murder of Kilverby and the disappearance of the Passio Christi? Any thoughts?’

Cranston shook his head.

‘Neither have I.’ Athelstan sighed. ‘We are assured that chamber was secured locked and no one entered or left. Nevertheless, Kilverby was poisoned, the Passio Christi taken. We know the merchant was visited earlier that day. He showed the two monks the Passio Christi which was to be brought here on the morrow. The bloodstone was displayed in the solar. Kilverby, escorted by Crispin, then took it back to his chamber. Everything must have been in order. The bloodstone was locked away. We know that, we saw the locked coffer. Kilverby kept the keys round his neck. The chancery was also secured. Kilverby joined his family for supper before returning to his chamber. Only then does hell’s black spy, the killer, manifest himself, or herself.’ He added wistfully: ‘Certainly some hell-born soul contrived a trap which created this mystery.’

‘I talked to Crispin,’ Cranston declared. ‘I did the same with Jumble-guts.’

‘Who?’

‘One of my spies along Cheapside, called so because his belly rumbles like a drum. Both Crispin and Jumble-guts sing the same hymn. It would be almost impossible, as well as highly dangerous, to try and sell the bloodstone on the open market.’

‘So why was it stolen in the first place?’ Athelstan exclaimed. ‘My mistake, Sir John. We should discover as much as we can about that sacred ruby but. .’

Athelstan picked up his quill pen, stared at its plume then the point, dipped it in the ink and became lost in his own thoughts.

‘Friar?’

‘I’m thinking about the attacks on me, Sir John. No,’ Athelstan shook his head, ‘I cannot say much. I can only remember fragments that I cannot properly explain.’

‘Such as?’ Cranston demanded.

‘Oh, just who was where when that crossbow was loosed. The speed with which my assailant entered the charnel house and extinguished those torches just within the doorway.’ Athelstan shook his head. ‘Never mind. What we do have in this abbey is the Wyvern Company disliked and barely tolerated. Abbot Walter may have confidence in their presence if his abbey is ever attacked, yet I am sure he would like to rid himself of the old soldiers. They’re an embarrassment and possible provocation to the Upright Men who may have dispatched assassins to kill Hanep, Hyde and Brokersby. Our abbot is supposed to pay the Upright Men protection money, but for his own secret reasons, has withheld this.’ Athelstan stroked his face with the plume of his quill pen. ‘By the way, Sir John, you say you recognized Eleanor Remiet?’

‘I did, I’m sure.’ Cranston tapped his feet on the floor. ‘God send me his grace. I recognized her face but it’s years, decades ago.’ He glanced up. ‘Why do you ask?’

‘At first I wondered if Isabella Velours was the abbot’s mistress. Of course that’s not true. However, I believe she is not his niece but his daughter.’

‘What?’

‘Nor do I believe Eleanor Remiet is his sister.’ Athelstan continued: ‘Although I accept she’s Isabella’s mother. I am sure if we made careful search in certain parish and manor records we’d uncover a legion of lies regarding those precious three.’

‘We could do that.’

‘Come, Sir John, it would take months. Moreover, Lord Walter’s private life is not our concern, even if our abbot doesn’t give a fig about anything except that swan and his two women.’

‘You’ve little evidence for what you say.’

‘Sir John, why should the abbot be so concerned about his niece? No, Isabella is his daughter and, more importantly, she has just come of age and. .’

‘Needs a dowry,’ Cranston breathed.

‘Hence the money to the Upright Men being drained away along with whatever else Abbot Walter can seize.’

‘Do you think the Wyvern Company found out about Isabella?’

‘I doubt it.’ Athelstan stopped writing the cipher he always used to record his thoughts. ‘Quite honestly, I don’t think the Wyvern Company give a fig about Isabella being Abbot Walter’s niece or his daughter. They are more concerned about themselves.’

‘And Prior Alexander?’

‘Basically a good man with sympathies for the common folk. The reception of my parishioners was his work. I must thank him. We know one of his kinsman, a hedge priest, was hanged out of hand by the Wyvern Company. Prior Alexander may want revenge. He is still vigorous, able to wield a sword. He dislikes the Wyverns, whilst he was here when all three died.’ Athelstan put his tray aside, rose and stretched.

‘Do you think he suspects the truth about Isabella Velours?’

‘Perhaps, but Lord Walter can also trap him. Prior Alexander has, I believe, an inordinate love for Richer. The truth behind that relationship is difficult to discern but I suspect Prior Alexander indulges Richer. When they go into the city the prior is willing to take his young friend down to the quayside to search for foreign ships. Indeed,’ Athelstan sat down, ‘it is Richer who is the key to this mystery. He was sent here, I am certain, by his uncle, the Abbot of St Calliste, to retrieve the Passio Christi. Has he suborned Prior Alexander in order to achieve this? Perhaps. Did he or both of them kill the old soldiers including Chalk? I cannot say. What I am certain of is that Richer lies at the root of this. Look,’ Athelstan got to his feet, unbolted the door and stared out. The gallery outside was deserted. He could hear the plain chant from the church as the full choir intoned the psalm: ‘The Lord trains my arms for war, he prepares my hands for battle.’ Yes, he does, Athelstan reflected, closing the door. ‘Sir John, look at the facts. Kilverby once financed the Wyvern Company. He held the Passio Christi without protest. Time passes. Death beckons. Kilverby wants to prepare for judgement. The Wyvern Company move here. Kilverby visits them but he encounters Richer. He also meets another man frightened of approaching death, a defrocked priest, Master William Chalk. Oh yes, he was, remember?’

Cranston nodded.

‘To move to the arrow point. Apparently Richer put the fear of God into both men, especially Kilverby. He points out the terrible sacrilege which took place after Poitiers. Kilverby breaks from the likes of Wenlock. He wants nothing more to do with them. He’ll do penance, perform reparation, give up his luxurious life and go on pilgrimage. On the very day he departs he will make decisive restitution. He will leave the Passio Christi at a Benedictine Abbey.’

‘But that doesn’t explain his murder?’

‘No, Sir John. It certainly does not. Moreover, as you discovered during your last visit to Kilverby’s mansion, what did compel this hard-headed merchant to change, to want to rid himself of a sacred bloodstone he’d blithely held for years? Richer’s persuasive tongue? I don’t think so. In my view Kilverby saw or heard something which literally put the fear of God into him and that’s what Richer exploited so successfully. However, what that was and how Kilverby came to be murdered? I admit, there’s no logical answer to either of these questions.’

‘And the murders here?’

‘Again, I cannot see any logic behind their deaths. Hanep and Hyde were killed when Wenlock and Mahant were absent. Wenlock’s maimed hands are an impediment, though Mahant is a master swordsman. They were all sleeping when Brokersby was burnt to death and Osborne, by all accounts, has fled the abbey. All three murders demonstrated the Wyvern Company are very vulnerable. Perhaps that’s why Osborne fled. The Wyvern Company can no longer protect itself. As for who is the assassin? Prior Alexander? Richer? Both of them or someone else? The anchorite is certainly skilled in violent death with his own grievances against these former soldiers.’ Athelstan picked up another quill pen, dipped it into the ink and made further entries. ‘As regards to the deaths of the first two Wyverns, well, it could be the work of an assassin despatched by the Upright Men. It’s Brokersby’s death which intrigues me. Why the raging fire?’ He put the pen down. ‘How was that oil not only poured into a locked chamber but so close to the bed?’

‘Brother,’ the coroner sighed, ‘my eyes grow heavy. I must adjourn and reflect. I also need to despatch certain letters to the city. I want them to go at first light.’ Cranston walked over and gripped Athelstan’s shoulder. ‘No wandering this abbey by yourself little friar, promise me.’

Athelstan did. Cranston put on his boots, picked up his cloak, made his farewells and swept from the chamber. .

The anchorite had been dreaming about his days as the Hangman of Rochester. He woke in his anker house bathed in sweat and sat listening to the sounds of the abbey. Compline had been sung. The monks had shuffled out. Candles and lantern horns had been snuffed; only the occasional light gleamed but these solitary taper flames did little to repel the darkness. The anchorite peered around. The smells of the church, beeswax, burning charcoal, incense and that strange mustiness still swirled. The anchorite crossed himself, knelt on the narrow prie-dieu and stared up at the crucifix. He’d had a good day, cheered by the sight of Athelstan’s parishioners. During his long walk he had planned more frescoes and wall paintings but now the day, was gone, night was the mistress. He strained his ears for other sounds – nothing! The abbey church had yet to be locked. The sacristan and his entourage still had to make their nightly patrol to ensure all lights were extinguished, doors secured, especially after the peace of the abbey had been so deeply disturbed. The anchorite had quietly marvelled at the shocking news. Brokersby had been visited by fire whilst Osborne had apparently fled. Was this God’s justice? Perhaps it was. After all, why should such killers be allowed to end their days in peace?

The anchorite rose and paced his cell. He paused at the whispering outside the anker slit. Was she back? Trying to control his fears and the icy tremors piercing his belly, the anchorite crept towards the slit then recoiled at the pasty white face which suddenly appeared there.

‘Hangman of Rochester,’ that spiteful mouth hissed, ‘are you not ready to pay?’

‘Pay? Pay?’ The anchorite gasped. ‘Pay for what?’

‘Blood money, surety for what you’ve done. Strip yourself of your wealth. Leave it on the ledge, the profits you have made. Money for Masses. .’

The anchorite retreated. He plucked up the coffer crammed with gold and silver coins. For peace, he thought, I’ll surrender this, a shimmering cascade through that slit to buy peace from all this. The anchorite grasped the coffer even tighter. He felt his stomach drawn like a bow string. If only she’d go and leave him alone! He glimpsed movement at the anker-slit, a trail of scraggly hair. Was she gone? He startled as the door was pushed and rattled against its bolts. The anchorite opened his mouth in a silent scream. The door shook again, a threatening rattle. Agnes Rednal was trying to break in! He dropped the coffer and hurled himself at the door screaming and cursing, banging with his fists, pleading for that hell creature to leave him alone.

The following morning after his dawn Mass, Athelstan heard about the disturbance at the anker house. He was divesting in the chantry chapel assisted by Brother Simon, who’d acted as his acolyte and altar boy.

‘Screaming and banging he was,’ Brother Simon exclaimed. ‘The sacristan had just entered the church when it happened, a man possessed or so they say. Our anchorite is haunted by demons.’

Athelstan thanked Simon. Curious, he made his way down to the anker house and tapped on the door.

‘Who is it?’

Athelstan glanced at the slit and glimpsed the anchorite’s long white fingers grasping the sill.

‘Brother Athelstan, friend. I wonder if all is well? I mean no harm. If you would like to speak?’

To his surprise he heard the rattle of chains, bolts being drawn and the low door swung open. Athelstan bent his head, entered the anker house and straightened up. The anchorite immediately knelt and asked for his blessing. Athelstan gave this and stared around. The cell was rather large, apparently a disused chantry chapel – its wooden screen had been removed and a wall built across the gap. A comfortable, sweet-smelling chamber with bed, chest, coffers and a lavarium; a table stood under a window of clear glass, beside it a lectern then a prie-dieu with pegs driven into a wall on which to hang clothes. A small brazier warmed the air with scented smoke whilst a five branch candle spigot and a lantern horn provided more light. The anchorite, still agitated, invited Athelstan to the chair while he drew up a stool and gazed expectantly at the friar.

‘What happened?’ Athelstan asked.

The anchorite told him. When he’d finished Athelstan shook his head in disbelief.

‘And this has happened before?’

‘Oh yes, Brother, I always see her, at least in my mind’s eye. I always did but now, during these last few weeks, she comes here demanding vengeance and blood money.’

‘Blood money?’ Athelstan scoffed. ‘For what?’

‘For her death.’

‘Well, what money?’

The anchorite rose, went into the shadows and returned carrying a casket which he unlocked with a key from a ring attached to his leather belt. Athelstan gasped at the mound of glistening coins, good, sound silver and gold. He grasped a handful, weighing it carefully before putting it back.

‘My inheritance,’ the anchorite explained, ‘after my parents died, as well as what I’ve earned over the years both as a painter and hangman. Remember, I am allowed all my victims’ goods while some pay well for their going to be brisk.’ The anchorite paused, muttering a prayer. ‘Brother, why am I being haunted? If she wants blood money should I give it to her?’

‘She demanded that last night?’

‘Yes, she did and I nearly agreed.’

‘Look,’ Athelstan took the coffer from the anchorite’s hands and placed it on the ground, ‘demons walk, we know that. The Lords of the Air float by in hordes. Devils whisper in corners and all kind of darksmen roam the wilderness of the human soul. Ghosts cluster close before our mind’s eye or, indeed, to our physical senses. Nevertheless, I’ve never heard of a ghost demanding money. Moreover, why does she only appear when the abbey falls silent and deserted?’

The anchorite stared back, unconvinced.

‘You have eerie imaginings, my friend,’ Athelstan continued. ‘Undoubtedly the death of Agnes Rednal haunts you but not her soul. Please,’ Athelstan smiled, ‘trust me.’

The anchorite just kept staring, face all haggard.

‘You have eaten and drunk?’ Athelstan asked gently. ‘Refreshment, as Sir John says, is good for the soul as well as the body. I promise you, I will plumb these mysteries which brood so close to you.’

‘And those other mysteries, the murders here?’

‘My friend,’ Athelstan gestured round, ‘we still stumble and fall.’

‘I heard about your panic in the charnel house. Brother Athelstan, tread warily here.’

‘You said something similar when we first met. You told me you had things to say,’ Athelstan added. ‘You still nurse grievances against the Wyvern Company about your wife and child?’

‘Yes, my poor family.’ The anchorite rubbed the side of his head. ‘Sometimes I see them as I do Agnes Rednal.’ He glanced up pitifully. ‘That’s what I wanted to confess last time. My deep loathing for those soldiers yet I did not kill them.’

Athelstan stared at the man’s strong, claw-like hands.

‘You have the strength and skill,’ Athelstan murmured, ‘you are deeply troubled.’

The anchorite sprang to his feet then sat down face in his hands.

‘True, I am deeply troubled. Agnes Rednal crawls on to my bed.’ He pointed at the ledger resting on the desk. ‘I describe my dreams, my visions. Brother, I cannot distinguish between what is real and what is my imagining.’

‘Friend,’ Athelstan replied briskly, ‘you live in this anker house, you’re close to God. You are, I believe, a good man of troubled soul though your wits remain sharp. So answer my questions. Keep with the land of the living. Help me to pursue justice.’

The anchorite sighed and took away his hands.

‘Your questions?’

‘Good. You came here when?’

‘About three years ago.’

‘Did you ever talk or converse with the Wyvern Company?’

‘What do you think? I voiced my resentment of them. Once, shortly after my arrival, they came here to gape and stare. I told them who I was and what chains bound us together from the past.’

‘And?’

‘They just protested and walked away. They stayed away except for Chalk, who fell ill. I saw him here with Sub-Prior Richer; they sat in the shriving pew close to the Lady chapel. Of course all I could glimpse was him kneeling at the prie-dieu and the monk in the shriving chair. At the time I laughed to myself. I hoped Chalk would confess his sins against me and mine. I prayed such offences would thrust themselves up like black, stinking shrubs in his midnight soul.’ The anchorite breathed out noisily. ‘God forgive me, he must have done. One day Chalk, his face as white as his name, came and knelt outside my door. He begged my forgiveness for what he had done. He confessed it was a memory, something which happened on a summer’s day, a few heart beats when he’d been a soldier and didn’t give a fig about anyone. Oh, I forgave him, I had to. For his penance I asked him to pray for me and mine every day. He promised he would.’ The anchorite pulled a face. ‘Apart from that the Wyvern Company kept their distance except, strangely enough, Ailward Hyde. On the day he was murdered, he came into church. He was worried. He stopped to look at my paintings. He’d done this before. I shared a few words with him then something alarmed him. A figure crept in down near the Lady chapel. I heard a clatter as if a weapon was dropped. Hyde was also curious and followed in silent pursuit.’

‘Who was this figure?’

‘I don’t know; perhaps a monk. Anyway, Hyde took off in pursuit but someone else followed him, I’m certain of it. I glimpsed a black monk’s robe then it was gone, that’s all I can say.’

Athelstan nodded understandingly. ‘But let us go back, my friend: Kilverby, was he shriven by Richer?’

‘Yes.’

‘And what about Kilverby’s clerk, Crispin?’

The anchorite blinked and shook his head. ‘I saw Crispin, he often came here with his master. I noticed nothing untoward except one afternoon early last summer, around the Feast of the Baptist. Kilverby arrived at St Fulcher’s to pray before the rood screen. Crispin was with him. They, like many people, forgot about me as they strolled up and down the south aisle. On that particular day they were arguing.’

‘About what?’

‘Oh, Crispin coming to lodge here at the abbey. Crispin was respectful but insisted that he too should leave with his master. Kilverby strongly objected to this, saying Crispin’s eyes were failing. Crispin then said something rather strange: “I don’t want to live back here again”.’

‘I am sorry?’

‘I listened more attentively. Apparently, many decades ago, Kilverby and Crispin studied here as novices, though both later left. I heard similar gossip amongst the brothers. Anyway, Kilverby tried to lighten Crispin’s mood, teasing him about being left-handed and how the Master of the Novices had tried to force him to use his right. The merchant reminisced how Crispin used to be punished for that as Kilverby was for gnawing on the end of every pen or brush. He and Crispin laughed at the foibles of this monk or that. Abbot Walter’s early days were mentioned, some gossip or scandal about him, but their voices became muted and they moved on.’ The anchorite rose and paced up and down the cell. He paused, tapped the crucifix and glanced down at Athelstan.

‘Brother, I am lost in my own puzzle of dreams and fears. I see things. I overhear conversations but there’s little else. When we first met I had so much to say; I was being threatened. True, at first, I rejoiced in the deaths of Hanep and Hyde. Now I am beginning to wonder. So much hate, so much resentment all because of deep, hidden sins.’ He paused. ‘Brother?’

‘Yes?’

‘I would like to leave here. Would St Erconwald have an anker house?’ He kicked the coffer. ‘I have the money to pay for its construction. I could help your painter.’

Athelstan was about to refuse but softened at the man’s pleading look.

‘Friar!’ Cranston’s booming voice echoed along the south aisle.

‘I must go.’ Athelstan rose. ‘As for your request, let me see.’ The friar left the anker house and found Cranston had moved across the church to admire a scene painted from the Book of Daniel about Susannah facing her lecherous accusers.

‘Sir John, good morrow.’

‘And the same to you, little friar. I’ve heard Mass, I’ve broke my fast. What. .’ He paused as Wenlock and Mahant, their cloaks glistening with wet, came up the aisle. Athelstan noticed the daggers pushed into their war belts. Men of violence, Athelstan reflected, yet they looked cowed, Mahant especially, his hard eyes now red-rimmed, his cheeks unshaven.

‘We are leaving,’ Wenlock declared, ‘no, no, not for good.’

‘I hope not,’ Cranston retorted. ‘You’ll stay here. I sent a lay brother into the city. I’ve asked the sheriff to issue writs for the fugitive Henry Osborne.’

‘He’s not a. .’

‘Master Wenlock, he is. Osborne fled from here by night. He could be the assassin we are hunting.’

‘Never – ’

‘Everyone,’ Cranston insisted, ‘including both of you, are suspects, Osborne even more so. His description will be proclaimed in Cheapside, posted on the ‘ Si Quis’ door at St Paul’s as well as its Great Cross. If Osborne does not surrender himself in ten days he will be declared utlegatum– an outlaw, a wolfshead.’

Mahant glanced sharply at Wenlock, who simply shook his head.

‘Just as well,’ Mahant muttered. ‘It’s best if he’s taken.’

‘Why?’ Cranston demanded.

‘Osborne was our treasurer,’ Wenlock explained. ‘I am sorry. We did not mention this before. When he left Osborne took most of our gold and silver with him. We are going into London to search for him ourselves.’

‘Why there?’ Athelstan asked.

‘Osborne is not a country bumpkin,’ Wenlock replied. ‘He also likes the ladies. Perhaps we’ll find him in the stews or some other brothel.’ Wenlock shrugged. ‘Athelstan, Sir John?’

Both men bowed and left.

‘I’m not too happy,’ Cranston whispered, ‘I would like everyone to stay where they are but so far we have little proof to detain them, yes?’ Cranston’s gaze travelled back to the painting of Susannah. He walked up to it, stared hard for a while then abruptly jumped up and down like a little boy. ‘Lady Purity!’ he exclaimed. ‘Lady Purity, also known as “Mistress Quicksilver”.’

‘Sir John, are you madcap?’

Cranston pointed to the picture of Susannah then grasped Athelstan firmly by the shoulders, his blue eyes blazing with good humour.

‘Eleanor Remiet,’ he whispered, pushing his face close to Athelstan. ‘Eleanor Remiet be damned! She’s Lady Purity. Athelstan, I know London. What you told me about the anchorite? I certainly remember him as an excellent hangman. Nor can I forget that murderous harridan Agnes Rednal whilst Wolfsbane was a demon incarnate. They’ve all crossed my path. I’ve certainly crossed theirs and others. Do you recall Alice Perrers?’

‘The mistress of the late King Edward, she stayed long enough by his corpse to strip it of rings and every other precious item.’

‘Living like a nun now out in Essex.’ Cranston chuckled. ‘Oh yes, I’ve met them all, little friar, the good, the bad and the downright wicked.’

‘And this Lady Purity?’

‘Stare at the painting of Susannah, Friar, gaze at her face. I’ve been studying it since I arrived here this morning. I know that face! This fresco was executed many years ago but the painter certainly used someone as his image.’

‘Eleanor Remiet?’

‘Look and judge.’

Athelstan did. Cranston snatched a flaming cresset from its sconce and held it up to illuminate the beautiful face shrouded by a mass of golden curls, the downcast eyes, the graceful way that Innocent from the Book of Daniel kept her cloak about her naked body. Athelstan stared, fascinated by the compelling beauty of the woman’s face and the more he looked his doubts began to crumble. The artist, whoever he was, had used the woman now calling herself Eleanor Remiet as his mirror for this biblical heroine. To be sure, Remiet was now old, her face ravaged by time, but a hidden glow of beauty still remained in those haughty features and Athelstan could detect the same in the wall painting before him.

‘Sir John,’ Athelstan stepped back, ‘you are correct. Who was this Lady Purity?’

‘A great courtesan of Cheapside. I used to woo her from afar. She certainly wasn’t for the likes of young Jack Cranston, freshly inducted into the Inns of Court, oh no, but I adored her from a distance, worshipping at her altar. I did all I could to discover more about her.’

‘And?’

‘Lady Purity, as she called herself, reserved her favours for the great ones of the land. She also acquired a rather sinister reputation.’

‘As?’

‘As a cozening blackmailer who, when it suited her, could threaten a cleric with a summons to the Archdeacon’s court or an errant husband with the wrath of his wife. She earned money swiftly and smoothly in both her callings, hence her nickname, “Mistress Quicksilver”. As for her title, “Lady Purity”,’ Cranston laughed, ‘well, that was because of her pious ways, at least publicly. In her youth she was a great beauty who acted so innocently, so decorously, you’d think butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth. She was the toast. .’ Cranston walked away as shouts and cries from outside rose and fell. Athelstan remained rooted to the spot, lost in his own wild tumble of thoughts.

‘As I said,’ Cranston continued, coming back, ‘she was the toast of Cheapside. Athelstan, you were right about her relationship with our abbot, that’s what started me thinking. Eleanor Remiet is not the abbot’s sister but his leman.’ Cranston chuckled to himself. ‘She is definitely the mother of the lovely Isabella who, of course, is the abbot’s natural daughter, certainly not his niece. They are, in the eyes of God, though not Holy Mother Church, husband, wife and child. Lady Purity or Mistress Quicksilver, whatever her name, will have her claws very deep into our Lord Abbot. She will demand the best sustenance and purveyance for both herself and her daughter. In her youth, saintly Susannah or not, Lady Purity had a hunger for gold and silver. The passing of the years and the needs of young Isabella will have only whetted her appetite as sharp as a knife.’

‘Which would explain why the abbot stopped paying the Upright Men?’

‘Aye, and God knows what else he has misappropriated. I think it’s time-’

‘Not yet,’ Athelstan gripped Cranston’s sleeve, ‘not yet my Lord Coroner, let me first reflect; there are other matters. .’

Athelstan broke off as the hubbub outside grew. He and Cranston went through a side door into the porch. A group of brothers were gathered round a barrow being pushed up the path. Exclamations rang out, the monks, jostling each other, blocked Athelstan’s view of what was in the barrow. They parted and Athelstan groaned in sheer pity at the horror piled there, the long graceful neck now twisted, the glorious white plumage piled in dirty disarray – Leda the swan! Athelstan stopped the barrow and stared down at the once magnificent bird.

‘How did it happen?’

‘Hanged! Hanged!’ Brother Simon pushed his way through. ‘We found Leda hanged on the gallows near the watergate.’

Athelstan sketched a blessing over the dead bird.

‘Abbot Walter will be distraught,’ one of the brothers exclaimed. ‘He will mourn as if for a loved one.’

‘Aye, but does he love any of us?’ another added.