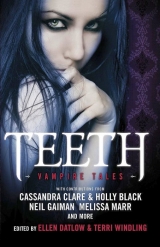

Текст книги "Teeth: Vampire Tales"

Автор книги: Neil Gaiman

Соавторы: Cassandra Clare,Catherynne M. Valente,Cecil Castellucci,Ellen Datlow,Christopher Barzak,Kathe Koja,Tanith Lee,Lucius Shepard,Jeffrey Ford,Steve Berman

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Josh nodded, thinking furiously. He was not going to be left behind in flyover country if he could help it.

Two more of the Quality showed up at Ivan’s at the next open evening. One looked the part – tall, pale, and high shouldered like a vulture (an effect undercut by his cowboy boots, ironed jeans, and Western shirt with pearl-snap buttons). There was no mystery about what he was after: Several pounds of Indian fetish necklaces decorated his sunken chest.

The other, a chunky Asian-looking woman with a flat-top haircut, wore chains and bunches of keys jingling from her belt, her boots, her leather vest.

“What’s she looking for, whips and handcuffs?” Josh whispered.

Crystal smirked at him. “Dummy. That’s Alicia Chung. Odette says she has the best collection of nineteenth-century opera ephemera in America.”

“She’s looking for old opera posters around here?”

Crystal shrugged. “You never know. That’s part of the challenge.”

In the workroom after closing, the first thing Odette said was “If Chung is here, it won’t be long before MacCardle arrives. We pack up tonight, Crystal.”

Josh broke an icy sweat. He had no time for finesse.

“Odette?” His voice cracked. “Take me, too.”

“No,” she said. She didn’t even look at him.

“Crystal travels with you!”

“Crystal is Quality, and she has no living family. Shall we kill your mother and father so they won’t come searching for you?”

With Crystal’s voice in his ears (“Ooh, that’s cold, Odette!”), Josh ran into the bathroom and threw up. He drove home without remembering to turn on his headlights and fell asleep in his clothes, dreaming about Annie Frye biting his neck. Later he sat in the dark banging out the blackest chords he could get from his keyboard.

His band was gone, nobody from school wanted to hang with him, and now even the vampires were taking off.

His mom knocked on the bedroom door at seven a.m. and asked if he wanted to “talk about” anything. “Your music sounds so sad, hon.” Like he was writing his songs for her!

“It’s just music.” He hunched over the Casio, waiting for her to leave. How could he stand to live in this house one more day?

She stepped inside. “Josh, I’m picking up signals here. Are you thinking of leaving town with your new friends?”

He panicked, then realized she only meant his imaginary musician pals. “No.”

“All the same, I think it’s time I met them,” she said firmly.

“Why can’t you leave me alone? You’re just making everything worse!”

“You’re doing that brilliantly for yourself,” she retorted. They yelled back and forth, each trying to inflict maximum damage without actually drawing blood, until she clattered off downstairs to finish crating pictures for a gallery show in San Jose. The hammering was fierce.

She was going out there for her show’s opening, naturally.

Everybody could leave flyover country for the real, creative world of accomplishment and success, except Josh.

He slipped into her studio after she’d left. As a kid, he had spent so much time here while his mom worked. The bright array of colors, the bristly and sable-soft brushes, and the rainbow-smeared paint rags had kept him fascinated for hours. There on the windowsill, just as he’d remembered during their argument, sat something that just might convince Odette to take him with her.

Ivan had belonged to a biker gang for a few years. Later on, he’d made a memento of that time in his life and then asked Josh’s mother to keep it for him (his own wife wanted no reminders of those days in her house).

What Ivan had done was to twist silver wire into the form of a gleaming, three-inch-high motorbike, with turquoise-disk beads for wheels. The thing was beautiful as only a lovingly made miniature can be. It looked like a jeweled dragonfly. Visitors had offered Josh’s mother money for it.

Value, uniqueness, handcrafted beauty – it was perfect.

Josh quickly packed it, wrapped in tissues, into a little cardboard box that used to hold a Christmas ornament. At work, he stashed it in a drawer of the oak desk in the Victoriana booth, where he sometimes went for naps when the vampires’ snacking wore him out. Odette would come tonight, after her final antiquing run through town, before she took off for good. This would be his one and only chance to persuade her.

After closing time, he dashed out for pizza. When he got back to the darkened mall, he was startled to find Crystal sitting at the oak desk with the little brass lamp turned on.

“How’d you get in?” he asked.

She gave a sullen shrug. The package sat open on the desk in front of her.

“Where’s Odette?” The silent mall floor had never looked so dark.

“She’s late,” Crystal said. “I was tired of waiting, so I hitched a ride over from the Top. This is something of yours, right? What is it, anyway?”

“A going-away present for Odette. I got something for you, too,” he added, trying frantically to think of what he could give to Crystal.

“Yeah?” Her red leather purse, heavy with quarters for the game machines, swung on its thin strap in jerky movements like the tail of an angry cat. “You were gonna give me something? You liar, Josh.”

He wondered, with a shiver, if some of the coins making the little red purse bulge were from the meth head’s haul.

Suddenly she screamed, “You think you can buy Odette with this little shiny piece of trash? You pretend to be my friend, but you just want to take my place!”

She lashed at him with the purse. He dodged, tripped, and toppled helplessly. The back of his head smacked the floor with stunning force.

Crystal threw herself on top of him, guzzling at his throat as he passed out.

He woke up lying on a thirties settee outside Ivan’s office, deep in the heart of the mall. In the office, the computer monitor glowed with light that seemed unnaturally bright, illuminating the little room and the hallway outside it.

His shirt stuck to his chest and his neck was stiff. He felt his throat. There was a damp, painless tear in the flesh on one side.

“Crystal is a messy eater, but don’t worry, that will heal quickly.” Odette, perched on a chair by the end of the settee, held the miniature bike in her hands. “I think you brought this for me? Thank you, Josh. It’s very beautiful.”

He sat up. His mouth tasted sharply metallic, but nothing hurt.

“Where’s Crystal?”

“She ran off,” Odette said. “She knows she’s in serious trouble with me for killing you. Remember what I said about adolescent impulsiveness? Now you see what I meant. She won’t last long on her own, not with others of the Quality starting to show up here and my protection withdrawn. It’s too bad, but frankly it’s for the best. I’m tired of her tantrums.”

He felt a slow, chilly ripple of fear. “Killing me?”

“Effectively, yes, but I arrived in time to divert the process. The taste in your mouth is my blood. It’s a necessary exchange that also provides a soothing first meal for you, in your revivified state. You don’t want to begin your undead life crazed and stupid with hunger.”

He licked his front teeth, which had a strange feel, like too much. His stomach churned briefly. “I thought you didn’t want to. turn. ”

She sniffed. “Of course not. Who needs another teenaged vampire? But dead young bodies raise questions, and Crystal already left one lying around out by the airport. Besides, with her gone I have a job opening. Your selection of this” – she carefully set the little bike on the table at her elbow – “shows an educable eye, at least. With coaching, I suppose you can be made into a passable member of the Quality.”

Coaching? He might as well have gone back to school!

She stood, smoothing down her skirt, and picked up his canvas tote from the floor at her feet. “I found this in your locker. The sweatshirt is yours, isn’t it? Take off that T-shirt and put this on. It’s none too clean, but you can’t walk around looking like a gory movie zombie. Then you must leave a note for your family. Say you’ve gone to seek your fortune.”

Thoughts lit up like silent sheet lightning in his mind while he worked the blood-crusted T-shirt off over his head. His life, his friends, his home – all that was over, and she’d just been trying to get rid of him when she’d said, before, about killing his parents. But there was no going back. The upside was, he would be getting out of here at last, traveling with Odette out into the real world.

Was that why he felt high, instead of all bleak and tortured about waking up undead?

Then it hit him: undead? He was finally going to get to live.

He punched the air and whooped. “Look out, Colin Meloy! Josh Burnham’s songs are coming down!”

Pawing around inquisitively in the tote bag, Odette glanced up. “Forget about your songs, Josh. You died. The undead do not create: not babies, not art, not music, not even recipes or dress designs. I’m sorry, but that’s our reality.”

“You don’t get it!” he crowed. “Listen, I’m still a beginner, but I’m good – I know I am. Now I have years – centuries even – to turn myself into the best damn singer-songwriter ever! So what if I never mature past where I am now, like you said about Crystal? Staying young is success in the music business! I can use the Eye to get top players to work with me, to teach me – ”

“You can learn skills,” she said with forced patience. “You can imitate. But you can’t create, not even if you used to have the genius of a budding Sondheim, which you did not. According to Crystal, your lyrical gift was. let’s say, minor. I hope you’re not going to be tiresome about this, Josh.”

“Crystal’s just jealous!” Buoyed by the exhilaration of getting some payback at last for his weeks of helpless servitude, he shouted, “You’re jealous! She told me about you, how you made jewelry for rich people – ”

Odette snapped, “That’s someone else. I designed tapestries. As a new made, you’re entitled to a little rudeness, but at least take the trouble to get the facts right.”

“But the thing is, you were already old – your talent was all used up by the time you got turned, wasn’t it? So now you can’t stand to admit that anybody else still has it!”

“My talent,” she said icily, “which was not just considerable but still unfolding, was extinguished completely and forever – just like yours – when I became what you are now.” She fixed him with a dragon glare and hissed, “Stupid boy, why do you think I collect?”

He almost laughed: What was this, some weird horror-movie version of fighting with his mother? Fine, he was stoked. “It’s different for me! I’m just getting started, and now I can go on getting better and better forever!”

With a shrug, she turned back to the contents of the tote bag. “You can try; who knows, you might even have some commercial success – ”

She stopped, holding up a fantasy-style chalice he’d made in ceramics class at the arts center. It was a sagging blob that couldn’t even stand solidly on its crooked foot.

“What’s this?”

“You should know,” he muttered, embarrassed. “You’re the expert on valuable things. It’s arts and crafts, that’s all, from back when I was still trying to find my way, my art. I brought all that stuff in here to try to sell it, only I forgot – I’ve been kind of distracted, you know?”

“You made this.” She ran the ball of her thumb along the thickly glazed surface, which he had decorated with sloppy swirls of lemon and indigo.

“So what?” he said. “Here, just toss that whole bag of crap.” There was a trash can outside the office door. He shoved it toward her with his foot.

Odette gently put the cup aside. She reached back into the tote bag and drew from the bottom a wad of crumpled fabric.

Oh, no, not that damned needlepoint!

In his fiber arts class, he had been crazy enough to try to reproduce an Aztec cape, brilliant with the layered feathers of tropical birds, like one he’d seen in the museum. He’d just learned the basic diagonal stitch, so the rectangular canvas had warped into a diamondlike shape. Worse, frustrated that the woolen yarns weren’t glossy enough, he’d added splinters of metal, glazed pottery, and glass, shiny bits and pieces knotted and sewn onto the unevenly stitched surface.

That wiseass Mickey Craig had caught him working on it once and had teased him for “sewing, like a girl.” That was when Josh had quit the class and hidden the unfinished canvas in his closet where nobody would ever see it.

Yeah; his luck.

Maybe he could convince Odette that his mother had made it.

“God in heaven,” Odette said flatly. “God. In. Heaven. If I ever catch up with that girl, I will tear off her head.”

Her eyes glared from a face tense with fury; but he saw a shine of moisture on her cheek.

Odette was crying.

And there it was, the kernel of the first great song of his undead life, a soul-ripping blast about losing everything and winning everything, to mark the end of his last summer as a miserable, live human kid: “Tears of a Vampire.” All he had to do was come up with a couple of starter lines, and then find a tune to work with.

All he had to do was. why couldn’t he think?

All he had to do. his thoughts hung cool and still as settled fog. He found himself staring at the crude, lumpy canvas, vivid and glowing, stretched between Odette’s bony fists.

He began to see it, this cockeyed thing that his own fumbling, amateurish hands had made. Its grimy, raveling edges framed a rich fall of parrot-bright colors, all studded with glittering fragments.

He hadn’t even finished it, but it was beautiful.

Oh, he thought. Oh.

This was it – this was what he should have been doing all along – not drawing comics or struggling with song lyrics, but crafting this kind of mind-blowing interplay of colors, shapes, and textures. This was his true art, his breakout talent.

So why couldn’t he picture it as a finished piece? He stretched his eyes wide open, squinted them almost shut, but he could only see it right there in front of him exactly as it was, abandoned and incomplete. His mind, flat and gray and quiet, offered nothing, except for a faint but rising tremor of dread.

Because although he couldn’t describe the stark look on Odette’s face in clever lyrics anymore, he understood it perfectly now – from the inside. It was the expression of someone staring into an endless future of absolute sterility, unable to produce one single creation of originality, beauty, or inspiration ever again.

If Josh wanted all that back – originality, inspiration, and beauty, only everything he had ever really wanted – he would have to get it the same way that Odette, or any of the Quality, got it.

He would have to begin collecting.

The List of Definite Endings

by KAARON WARREN

Sometimes partying felt like punishment. Claudia hated large groups of people, vampires included. They had secret jokes she didn’t get, and the conversation always moved too fast for her.

She liked to be with one person, or two. Talking about life and the future. About the past. She met people who’d seen history being made and were alive to talk about it. This was interesting to her. Not empty nights of dancing, laughing, feasting, sex. Perhaps she was too earnest, that was the problem. The rest of them were without care or thought. She wished she could be that way, but there was too much left of her soft mortal self.

Her boyfriend, Joel, waved his hand in front of her face. “Aren’t you hungry? Let’s go feast.” He poked her. “Stop dreaming. Let’s go party. The night’s coming in and you’re sitting around like you don’t wanna get fed.”

She felt a deep gnawing in her stomach. “Yes, I’m hungry. Of course I’m hungry. But I don’t feel like eating in a group.”

Joel rolled his eyes. “You bore me. Do you realize that? Bored bored bored.”

“Well, I’m bored with all this, too. Don’t you get sick of it? The relentlessness? Don’t you get tired of always being nineteen? Don’t you want to know what it’s like to be thirty? Forty?”

Claudia had been turned in 1942, three weeks before her final high school exams, something she’d always regretted. She’d studied hard, really hard, and she knew her stuff. She could write an essay on each of Henry VIII’s wives, and on child mortality rates around the world, and on the voting systems of almost any country you could name. They didn’t talk about the war in class. Their teachers said the facts changed too quickly and that they would have to wait and see. If the Germans won, then the history books would all have to be changed. Everybody knew that.

She was the first girl in her family to make it that far, one of only five girls finishing high school. Most of her friends were working in the shops, and some had even signed up as nurses, out saving the lives of brave soldiers. Finding brave, damaged husbands. Some days Claudia envied this ordinary life, others she knew she was due much more.

Her family was wealthy, always had been. It was because of shoes; people always needed shoes. Her father traveled a lot with the family shoe business, though Claudia knew there was more to it than that. He came back exhausted from his sales trips, often injured. Always his fingers covered with cuts and splinters, his eyes bruised. Scratches on his arms. While she studied, her mother fed her in a constant, perfectly timed stream of healthy and unhealthy snacks. Claudia knew the rest of the family went without so that she would have enough food to study on. A rare and beautiful apple. Thick slices of bread with butter and raspberry jam. Sometimes a piece of cake, if the neighbors pooled their resources. Claudia knew she did better than most.

Once her mother cooked a roast chicken and she put garlic all over it. Buttery garlic sauce to pour over the meat and the potatoes, fat slices of bread on the side.

This was the food she remembered now, when she thought about her past life. She hadn’t tasted garlic for close to seventy years, not in vegetable form, although sometimes the blood she drank was flavored with it. She liked that.

Early on she’d tried dead blood. It made her sick and weak for days. Most vampires don’t like to be around dead bodies. The smell turns them off – the waste of all that good, warm blood gone cold.

It was worth a try, though. Her vampire friends (all moved on, traveling the world) thought she was crazy, and any vampire she’d told since did as well. But every time she killed someone living, the memory of her parents lessened. She could almost feel it; a memory breaking loose and being dissolved by the foreign blood in her veins. She didn’t want to forget her parents, killed by the same vampires who’d turned her. She’d begged those monsters to turn her parents as well. Not kill them.

“We don’t want any old vampires,” they’d told Claudia. “No old rules, no tired old vampires. You need to be young to be one of us.” Claudia thought of her dad and the thousand cuts inflicted on him by the vampires. A father’s secret life as a vampire hunter come back to haunt him. He was almost dead when they dragged Claudia in and turned her in front of him. The last thing he saw was his daughter’s vampire eyes.

So all she had left of her parents was the memories of them, and when she could do it with no one watching, she drank the dead blood and put up with the weakness and nausea, for the sake of keeping memory.

Joel jumped onto the couch and backflipped off it, narrowly missing the coffee table. “Can a forty-year-old do that? You can’t seriously want to get old.”

“I don’t want to get old. But I do get tired of this stuff. This life. I’ve been doing it for seventy years. If they’d waited till I was twenty-one, at least. Twenty-one is a much easier age than nineteen. I could have found real jobs.”

“Twenty-one is old,” Joel said. “Who wants to be old? You might as well be, though. You’re sad and boring. Both things.” He walked away, as so many did. She’d see him around, but they were done with a relationship.

She knew that human boys were like that as well, sudden in their decisions, uncaring about softening the blow. But they grew up, became men. Learned how to care, be thoughtful. She’d watched it in Ken; seen him learn to love his wife, Sonia, and his children. All of them cared about one another and many other things.

She’d first met Ken fifty years earlier. She was out hunting with a group (she’d been a vampire twenty years, and the group constantly changed but essentially stayed the same), and they’d targeted a young, juicy man, sitting alone in a bar. Stools on either side of him empty, but the rest of the room full.

“You go,” one of the gang had insisted to Claudia. “You haven’t pulled one for a while.” Claudia hated this, the seduction of a victim. She hated the way they all fed off the same veins, the same blood. But she knew she had to join in or they might tear her apart.

She’d sat down by the lonely man. He’d looked around, as if surprised. “Is it okay if I sit here?” she’d asked.

He’d nodded. Speechless, she thought, at the idea that someone was talking to him. She felt terrible pity for him, glad his life was almost over.

She ordered a Coca-Cola; she didn’t want the barman asking for ID. Even in the ’60s they didn’t like letting minors get drunk.

“Seems quiet tonight,” she said. She was really bad at this. “You meeting anyone?” She had to find out if anyone would miss him for a while.

“No. No. Just came out because the apartment gets too quiet sometimes. So what’s your name? I’m Ken.”

“Claudia.” She didn’t want to know his name. “So you live alone?”

He didn’t answer.

“What do you do, then?”

“Work in the coroner’s office.”

“With dead bodies?”

“Yes, with dead bodies.” He said it angrily, as if ready for what would come next. It must have happened many times. People walking away in disgust.

“Cool,” she said. “Do you get to touch them?”

Ken took a sip of his beer. Didn’t speak.

“Do you touch the dead bodies?” Claudia asked again. It seemed important.

“Yeah, I touch them. I mostly do paperwork, though. Lists and things.”

“Oh.”

“But I do get to touch them. Have you ever touched one?” She could see him getting excited, thinking he might have found the right girl.

“I have.” Then something he said sparked. “What sort of lists do you mean?”

“I’m not supposed to talk about it. People aren’t supposed to know.”

She leaned closer. Across the room, the vampires were getting impatient, bored with her. Good. Let them find their own victim. “What sort of lists?”

“We keep a list of the terminally ill. Just so we can be forewarned. So the coroner can plan ahead. But people think it sounds bad, so we don’t really talk about it.”

She felt something like excitement growing.

“People on the list are going to die, no doubt? They are definitely going to die?”

“There’s little doubt, according to their doctors.”

She liked him for not saying, “We’re all going to die.”

“Can we go see some dead bodies?” she said. “I’d like that.”

She took his hand and led him past the vampire table on the way, and she shook her head at them, bent over to her boyfriend of the time (what was his name? She could barely remember his face), and whispered, “Leave this guy. Lives with his mother. Too much trouble.”

“Where are you going then?” her boyfriend asked. She knew he didn’t care.

“I’ll be back. Eat without me.”

The group of them physically turned their backs on her, but she didn’t care. She was used to that.

That was how she got the first list of the terminally ill. It was around the time that Adolf Eichmann was hanged for war crimes, and death was a focus in the minds of many. War was coming again, and yet each death was worth grieving, each life was worth remembering.

The first person from the list she killed was a woman in her forties. Claudia had never seen anyone in so much pain, with so much suffering around her. Daily she begged to die. Daily.

As Claudia took her, she said, “Thank you.”

There was no loss of memory as Claudia drank. Her parents remained clear.

Ken brought her updated versions of the list when she asked for them, never questioning what she wanted them for. Just her attention was enough. Their friendship grew even when he realized there was something up with her. He accepted it completely. They saw each other through life’s events, though more so for Ken than for her. She helped him to find Sonia, and to keep her. She had never met Sonia. It was best that way. But without Claudia, Ken would never have had the confidence to make a family life. He saw her through dozens of boyfriends, mostly vampires, and disapproved of them all.

At first when she and Ken were seen together, people mistook them for brother and sister. Then father and daughter. These days it was more like grandfather and granddaughter.

He had moved beyond the morgue to other jobs, but she had learned much in her eighty years and could hack into the computers for her lists whenever she needed to.

With the thought of Joel a dull ache and Ken very much on her mind, Claudia walked down to the seawall, enjoying the wind on her face and the smell of the salt. Joel said she didn’t really feel anything except for hunger, the sensation only a memory of what was. “You have a very good memory,” he said as an insult.

The seawall was high and the drop on the other side long. Teenagers would tightrope the wall, and even though it was as thick as a footpath, they teetered nervously.

Claudia walked slowly in the early-evening light. She liked this time, when there was enough natural light to see by. She liked the night falling, darkness growing. Liked the way it made her focus.

She sat on the wall, her feet dangling over. Pulling out her notebook, she checked her timetable. Joel didn’t know about this; none of them did. They already thought she was boring. Imagine what they’d think if they knew she had a list of future food sources, with their usual movements, phone numbers, all of it. She didn’t need notes to find her meal tonight, though. She knew where he’d be. Her notes were a simple comfort, this time, giving her a sense of control.

Darkness came down, and it seemed half the streetlights didn’t work. Sea spray meant the air was misty.

Up ahead, she saw someone on the wall, arms spread. There was no audience, so not a teenager showing bravado. She walked closer, saw it was Ken, his face wet.

He did not hear her approach. Tears. He was crying, passionately, as if he were emptying himself out.

“Ken?” she said. She’d been tracking him without his knowledge for six weeks now, knew his movements. After all these years of friendship, this was an odd intimacy. Watching this old man when he thought he was alone revealed nothing she didn’t know, though. He was a good, kind man who picked his nose.

Every morning he would leave the house and go to sit by the seawall, tempting himself until evening drew him home.

Looking at him, she thought, He’s almost the same age as I am. He remembers what I remember. The music, the movies. But he got old and I didn’t. Moments like that made her glad to be a vampire. She was glad to be living young in the twenty-first century, to have enjoyed the changes in the world as a young person.

“Ken,” she said again.

He turned to her voice. “Do you think I’d die if I jumped or just hurt myself?”

She climbed onto the wall, holding on tight to the edge. Looked over. “You’d hurt yourself. I guess you’d drown if you kept your face down.”

He sat slumped beside her. He had an odd smell, something not quite right.

It wasn’t a dead smell, not yet.

Ken, still balanced on the seawall, bent forward. “Am I on your list now?”

“Do you want me to call Sonia? The kids?” Claudia said. She knew what his answer would be.

“That wouldn’t do any good. She’d only come get me.”

Claudia squinted at him. “You don’t want her to?”

“No. No, I don’t. I don’t want her to see me again. It’s too hard for her.”

His voice was strained, and Claudia realized he was in great pain. “Are you. all right?” He tilted his head and looked at her properly. “You’ve always been kind.”

“My mum was kind. I guess it rubbed off.”

“Never lose that,” Ken said. “I wish I’d been kinder to everyone. Friends and strangers.”

Claudia didn’t say “It’s never too late,” because she could hear that it was.

“What’s wrong with you?” she said, vampire direct. She knew this answer as well, but he needed to say it. It was part of the process.

“Sick. Very sick. Pain ahead and long-drawn-out suffering for my kids. No kid should see a parent suffer. You shouldn’t have to see it.”

“What about the hospital? Can’t they help?”

“With the pain. But what’s the point? I want to pass quietly, peacefully, in control. Why can’t I have that?”

Claudia watched him for a while, then gazed out to sea. “Have you said good-bye to everyone? Tied it all up? Dying with a loose end is no good.”

He looked surprised. “Thanks. For listening, not trying to convince me.” His voice was tight, so full of pain Claudia could almost feel it. “I’ve tied it all up. I say good-bye, I love you, every day just in case. I’ve left special gifts for the grandchildren and messages for the great-grandchildren. I’ve apologized to people. It’s sorted. But I just can’t. ” He stopped, bent over, clutching his ears. “I’m too gutless to do what I need to do.”

Claudia felt her teeth tingle. “I can help,” she whispered. She snarled gently, then said it louder. “I can help.”

He turned, saw her teeth.

“The list? This is what you use the list for?”

She nodded. “I’ll be gentle,” she said, and she bent forward and drank deeply from the beautiful, pulsing vein in his neck. Drank till she was done, till he was; then she sat him on the ground, propped against the wall, and called an ambulance. She didn’t want him robbed, or his body stolen or damaged. His wife and kids needed to know quickly, to see him while he still looked close to life.

She watched from across the street until the ambulance arrived; then she walked home, feeling satisfied in her stomach and in the heart all the others assured her she didn’t have.