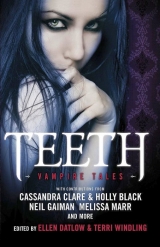

Текст книги "Teeth: Vampire Tales"

Автор книги: Neil Gaiman

Соавторы: Cassandra Clare,Catherynne M. Valente,Cecil Castellucci,Ellen Datlow,Christopher Barzak,Kathe Koja,Tanith Lee,Lucius Shepard,Jeffrey Ford,Steve Berman

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

The next day, Lottie said, “I’m afraid for our friendship.”

Retta said, “Lottie, why does everything with you have to be a chick flick?”

“It so does not have to be a chick flick!” said Lottie. “Seriously, Retta, you have been a total space-a-zoid for the past few weeks. It’s not cool. Everyone has noticed.”

“Who’s everyone?” said Retta. “You’re my only friend. I’m your only friend.”

“I’ve made some other friends, I guess,” said Lottie. She stopped walking down the mall concourse and took hold of Retta’s arm, squeezing gently. She’d brought Retta here, to the place where they’d spent most of their free time the past few years, in a last-ditch attempt to remind Retta about the bonds of their friendship, to surround her with shared memories of shopping and telling each other they looked good in certain outfits. But as Retta looked around at all the neon commerce and mass-produced entertainment surrounding her, she couldn’t help but sigh and wonder why none of any of it made sense to her any longer.

An enormous man eating a Frisbee-sized chocolate chip cookie passed behind Lottie as she waited for Retta to react to her declaration of having made other friends. The fat man was the sort of thing Lottie usually would have seen coming a mile away and would have commented on; and, at one time, the two of them would have bonded over making fun of him. Retta felt her face flush, embarrassed. She didn’t want to be the sort of person who boosted her sense of well-being by laughing at other people’s addictions, just because she herself didn’t know what she wanted so badly. And though she would have disapproved of Lottie’s blithe nastiness, now she just wanted her to say something terrible. It would have made ignoring her plaintive grasping easier.

“You’ve made other friends,” said Retta. “That’s nice. Who are they?”

Lottie winced. She was wearing a T-shirt Retta had bought in a store for boys a year ago, lent Lottie six months ago, and never gotten back. It had a yellow smiley face smack dab in the middle, stretched across Lottie’s ample chest. Lottie folded her arms over the face, as if to emphasize her unhappiness. Even the smiley face wasn’t allowed to be happy.

“It doesn’t matter who they are, Retta,” said Lottie.

“Loretta,” said Retta.

“What matters,” said Lottie, “is me and you. Us! What happened? We’ve spent our whole lives together and now we’re graduating next weekend and you’re all like, Whatever whatever, I’m in love with a vampire!”

“I am so not ‘Whatever whatever, I’m in love with a vampire!’” said Retta. “I’m. enlarging my environment. That’s all.”

“I can’t believe you will stand here and lie to me like that, Retta.”

“Seriously, Lottie?” said Retta. “We’re standing in front of Victoria’s Secret, not some hallowed monument to truth telling. And I’m not lying! Vampires are retarded. I could live for the rest of my life without seeing another vampire and be totally happy. Why won’t you let me be happy?”

Lottie’s jaw dropped. “I don’t even know you anymore, Retta.”

“Loretta.”

“Whatever,” said Lottie. “I can totally do without Loretta. Call me when Retta comes back.” She turned, arms still folded over the smiley face, hands clamped on her forearms like the mall air conditioning had just gotten way too chilly, and walked away in a hurry, leaning forward as if she were trudging uphill through driven snow.

Retta couldn’t feel the chill, though. She couldn’t feel anything, or wouldn’t allow herself, like Trevor had told her. And it wasn’t until Lottie had disappeared from sight that Retta remembered Lottie had driven them to the mall, that she was stranded.

She called her mom on her cell phone to ask if she would pick her up, but all she got was voice mail, her mother’s happy voice singing out the obvious fact that she couldn’t answer the phone. Retta looked at the time – six o’clock – and realized her parents had probably just arrived at their Friday Night Out, drinking wine in a restaurant with a bunch of people going ha ha ha, fanning their faces with their hands because something someone had just said was way too funny.

So she started walking.

Walking was what Retta did for the next few days, for the final week she would spend in that building that had housed her throughout her weekdays for the last few years of her teenaged life. She walked through her neighborhood, looking up through the new leaves at the sun, daring it, trying not to blink. She walked down the newly edged sidewalks on Monday and Tuesday, heading to school with her head hanging, watching her feet go back and forth. Lottie drove past both days, on the way to school, on the way home, but never looked at Retta, even though Retta looked at her, ready to wave. Lottie only sat in her car face forward, windows down, the wind blowing hair around her face.

Maybe it was better that way, spending the last week of classes getting used to not being around Lottie, who used those same last-minute days of their secondary education making an attempt at fast friendship with Tammie Galore, of all people, the ex-cheerleader turned vampire, which, it turned out, had been completely fabricated, as everyone had suspected. Retta supposed that Tammie’s backpedaling on her declaration of vampirism, along with her previous defection from the cheer squad, was what probably made her seem like a potential candidate for Lottie’s new best friend. In fact, by Thursday of that week, Tammie Galore was no longer Tammie but Tam-Tam, which everyone thought was cute and why hadn’t they all been calling her that for ages? Retta could have told them. Because Tam-Tam is not a cute name. Because Tam-Tam reeks of the desire to be someone you’re not.

She was walking home on Friday, taking long steps – trudging, really – when Trevor pulled alongside her in his car. She kept walking, though, so he began to follow, driving slowly, revving his Cadillac’s engine every now and then. “Hey, Lo,” he called out his window.

Retta looked over and said, “What?”

He grinned before saying, “Well, someone isn’t very happy.”

“That’s right,” said Retta. “I’m not happy. I’m not sad either, though, Trevor, I think you should know that.”

“What are you then?” said Trevor, and Retta stepped over the devil strip to the road, opened the passenger-side door even as his car idled forward, hopped in.

“I’m nothing,” she said, slamming the door shut. “I don’t feel anything. I’m affectless, a sufferer of ennui, apathetic, aemotional.”

“That’s not true,” said Trevor. He pushed down on the gas to go faster. “I tasted your feelings. You filled me up. I was full for days.”

“There could be a banquet inside me and I wouldn’t be able to taste any of it,” said Retta. She wanted to cry, because now was the sort of moment a person would cry, at a crisis point, confessing to their own flaws and weaknesses. But she couldn’t. If she had any tears, they weren’t raising their hands, volunteering their services.

When they pulled up to her house, Retta said, “I wonder if I could feel someone else’s? What if you were right? What if I’m like you and just don’t know it? What if I’m a vampire, only I can’t feel my own feelings?”

“I guess anything is possible,” said Trevor.

“If I was like that,” said Retta, “would you let me have some of yours?”

“Who? Me?” said Trevor, pointing at his chest, eyebrows rising higher on the slope of his shiny forehead.

“Yeah,” said Retta. “Is there anyone else in the car?”

“Sure,” said Trevor, shrugging. “Yeah, you bet.”

“Can we try then?” said Retta.

“You mean now?”

“Yeah,” said Retta. “Now. Why do you keep answering my questions with questions?”

“Sorry,” he said. “I guess. I just wasn’t prepared for this.”

“Because you came to feed on me, didn’t you?” said Retta. “Not the other way around.”

“Um.,” said Trevor. “I guess?”

“Don’t worry,” said Retta. “If you’re right and I have more feelings than even I’m aware of, there should be plenty. There should be more than enough for both of us.”

Back at her house, they sat down on the floor of her room, guru-style again, where Trevor showed Retta how to hold his hands properly, how to push forward, he explained, into someone else. “If you’re a vampire,” he said, “you’ll be able to do it. It’s not a trick. You’ll just be inside me with the slightest effort. Then, well, you’ll know what to do. Trust me.”

Retta touched her fingertips against the palms of his hands and pushed forward, as he’d instructed. Immediately the room went dark and she couldn’t even see the outlines of sunlight around the blind covering her window. She was inside him. And when she pushed a little further, she found them, his feelings, all tied up in the most intricate of knots. She took hold of one, unraveled it, slipped it inside her mouth, and started chewing. It was glorious between her teeth, bittersweet, like her mother’s expensive chocolate, soft and sticky as marzipan. It was the way she’d always imagined feeling should be. Visceral. Something she could sink her teeth into.

She untied another, and another, and another, until finally she felt herself lifting up, up, up.

Then – out of him.

She opened her eyes. Light hit her in the face, so much light she felt she might go blind like that street musician downtown. Is that what this did to him? A moment of blinding brilliance after his first taste of something wonderful? Then things began to readjust and her room was her room again, its peach walls surrounding her, and Trevor sat in front of her, sniffing, wiping the backs of his hands against his eyes like the greasy-haired kid had done at the assembly.

“That was hard,” he said.

“Then take some from me,” said Retta. “Take all of them. Just let me take some back when you’re finished.”

He stared at her for a long moment. The ridge of his fauxhawk looked like it was wilting. Finally he said, “Lo, this could be the start of something beautiful.”

She grinned, all teeth, and nodded.

In the morning, she rose with the first coos of the doves and thought about how symbolic all her actions were, how quickly everything she did now took on sudden significance. It was almost as if she could see everything, even herself, as if she were a benign witness to the actions of others and to the ones she herself was taking, as if she were someone else altogether different from the girl she had been. It was as if she floated above the town where she’d spent the first eighteen years of her life wondering how she’d gotten there, where she was, where she was going. Now she could see everything, as if it were no more than a map she’d hung on her wall, sticking bright red tacks into the places she wanted to visit.

Trevor was passed out on her bed. She’d drained him a few hours earlier, taken what he had and what she’d given, untied all but one of those bright little knots in his stomach, and left him empty. As she stepped carefully down the stairs with his keys in one hand and a bag of clothes in the other, she wondered what he would do when he woke, wondered what her parents would do when they, too, woke to find a vampire in their daughter’s bed instead of their daughter.

On the way out, she stopped in the kitchen to scrawl a message on the dry-erase board magnetized to the refrigerator. It’s been fun, she wrote in purple, her favorite color, and realized even as she wrote the message that purple was her favorite color. You are all lovely people. But I’m off to start my gap year. XO, Loretta!

When she was twenty hours away, drinking coffee as she drove down the interstate, eating up mile after beloved mile, her cell phone rang. It had been ringing for the past seventeen hours, but each time it had been one of her parents, and each time she didn’t answer, knowing that as soon as she pressed the talk button, nothing but hysterical screams and shouts would come out. This time, though, it was Lottie’s name on the screen that kept blinking. Retta answered, but before she could say anything, Lottie spoke in a sharp whisper.

“Retta,” she said. “I am sitting in a commencement assembly next to an empty seat with your name on it. Where are you? Your parents are freaking out and that vampire kid has filed a stolen vehicle report, so you’d better watch out. I guess I was wrong about you. You weren’t hot for him. You totally ditched him. But I still don’t understand. Tell me one thing, Retta,” said Lottie, and Retta imagined Lottie, arms folded over her chest, cell phone pressed to her ear, her plastic black gown and that square little hat, the golden tassel she would flip to the other side in half an hour, her legs crossed, the one on top bouncing furiously. “What happened? Why are you being such a bitch?”

“It’s Loretta!” screamed Loretta into the phone, like some rock star in the middle of a concert. “And it’s because I’m a vampire, Lottie! Because I’m a vampire! Because I’m a vampire!”

She flipped the phone shut and threw it out the window.

It was late morning. The sun was high and red all over. She snarled at herself in the rearview mirror, then laughed, pushed down on the gas, made the car go faster.

Bloody Sunrise

by NEIL GAIMAN

Every night when I crawl out of my grave

looking for someone to meet

some way that we’ll misbehave

Every night when I go out on the prowl

And then I fly through the night

With the bats and the owls

Every time I meet somebody

I think you might be the one

I’ve been on my own for too long

When I pull them closer to me

Bloody Sunrise comes again

leaves me hungry and alone

Every time

Bloody Sunrise comes again

And I’m nowhere to be found

every time

And you’re a memory and gone

something else that I can blame on

bloody sunrise

Every night I put on my smartest threads

and I go into the town

and I don’t even look dead

Every night I smile and I say hi

and no one ever smiles back

and if I could I’d just die

But when I’m lucky I do get lucky and

I think you might be the one

Even though the time is flying

When we get to the time of dying

Bloody Sunrise comes again

leaves me hungry and alone

Every time

Bloody Sunrise comes again

And I’m nowhere to be found

Every time

And you’re a memory and gone

something else that I can blame on

bloody sunrise

Flying

by DELIA SHERMAN

Lights dazzling her eyes. The platform underfoot, an island in a sea of emptiness. The bar of the trapeze, rigid and slightly tacky against her rosined palms. Far below, a wide sawdust ring surrounded by tiers of white balloons daubed with black dots, round eyes above gaping mouths.

She stretches her arms above her head, rises lightly to her toes, bends her knees, and leaps off as she has a thousand times before, the air a warm, popcorn-flavored breeze against her face. Belly, shoulder, and chest muscles tense as she cranks her legs up and over the bar. She swings by her knees, her ponytail tickling her neck and cheeks. The white balloons below bob and sway, and a tinkling music rises around her, punctuated with the uneven patter of applause.

Her father calls, “Hep,” and she flies to him, grasping his wrists, pendulums, releases, twists, returns to her trapeze, riding it to the platform. She lands, flourishes, bows. Applause swells, then the music falls away, all but the deep drum that gradually picks up its pace like a frightened heartbeat. She spreads her arms, lights flashing from silver spangles, bends her knees, and leaps into a shallow dive, skimming through the air like a swallow, swooping, somersaulting, free of the trapeze, of gravity, of fear. Until, at the very top of the tent, her arms and body turn to lead. The bobbing balloons and the sandy ring swell and mourn as, flailing helplessly, she falls.

And wakes.

Panting, Lenka sat up and fumbled at the bedside lamp. Damn, she hated that dream. At least this time she hadn’t fallen out of bed and woken her parents. That’s all she needed – Mama patting her down, asking briskly if she’d hurt herself, Papa watching over her mother’s shoulder with sleep-blurred, helpless eyes. They wouldn’t yell at her – they never yelled at her these days, even when she deserved it. They’d just tell her to rest and maybe suggest talking to the doctor. Well, she wouldn’t. She was finished with doctors and rest. She’d been in remission for nearly three months now. When her parents were out at work, she did calisthenics in her room, took runs through the neighborhood. Short runs – she was still pretty feeble. But she was getting stronger, she told herself, every day.

She’d be flying again, soon.

Lenka sat in the kitchen, glumly eating cereal, waiting for the slap of the morning paper on the doormat.

Mama and Papa were always talking about how getting the morning paper delivered was one of the perks of living in the same place for more than a few months. So was Lenka having her own room and a view with trees in it and a separate kitchen and living room, with a TV.

Lenka didn’t care about any of it. She preferred backstage – any backstage. It was where she’d grown up, practically where she’d been born, a space variously sized and furnished, the only constants the smells – makeup, sweat, and do-it-yourself dry-cleaning sheets – and her family: the Fabulous Flying Kubatovs.

At their height, right before Lenka got sick, there had been seven of them: Mama and Papa, her two older brothers and their wives, and Lenka herself – in sweats and leotards, in tights and sequins, hands bound with tape and ankles wrapped with Ace bandages, practicing, stretching, dressing, mending costumes, arguing cheerfully with the other acts, seeing that Lenka got her legally mandated hours of English, math, and social studies. Making her strong. Teaching her to fly.

The Cleveland Plain Dealer thumped on the mat. Lenka opened the door and picked it up as Mama came in.

“You’re awake early,” she accused.

Lenka slid into her chair. “I’m fine, Mama, really. I had a bad dream.”

Her mother rolled her eyes and turned to the refrigerator. “I’m making an egg for your father. You want one?”

“Ick,” Lenka said, and opened the paper to the entertainment section.

She skimmed the movie listings. Nothing she wanted to see – which was good, since movies cost money. Her brothers and sisters-in-law sent what they could, but mostly it had to go for rent and doctors. Having leukemia was crazy expensive, even with insurance, and jobs hard to come by. Mama was temping for an accounting firm. Papa was working the register at Giant Eagle. These jobs yielded enough for food and a family membership to the YMCA so Papa and Mama could keep in shape. But Lenka noticed, every time they talked to her brothers, touring with Ringling Bros. in Florida, how Mama got crabby and Papa’s jokes got even lamer than they usually were. They were as miserable in Cleveland as she was.

A headline caught her eye. CIRQUE DES CHAUVE-SOURIS CONVEYS CLASSIC CIRCUS MAGIC.

Lenka didn’t want to read it, but she couldn’t help herself. Fresh from the eastern European circuit, the Cirque des Chauve-souris is like a glance back into a vanished time. Ringmistress Battina brings the Old Country to the new with a show that is as Gilded Age as the antique wooden tent and the steam organ. The kids probably won’t get it. There are no clowns or flashy high-wire acts; no midway, no concessions, no trendy patter. There is, however, a bar with draft pilsner and some seriously fine acrobatics.

“There’s a circus in town,” Lenka said.

Her mother didn’t even turn from the stove. “No.”

“The tumblers are Czech – you ever hear of the Vaulting Sokols?” Mama shook her head. “And a cat act. You love cat acts. Please, Mama?”

Papa came in, hair wet from the shower, shirt half buttoned over his undershirt.

“Please what, berusko?”

“She wants to go to the circus, Joska,” her mother said. “I have already said no. You want fried egg or scrambled?”

Lenka pushed the paper toward her father. He shook his head without looking. “Your mother is right. Your immune system is compromised. Circus means children; children mean germs. Not a good atmosphere for you, princess mine.”

“It’s not a big-top show, Papa, just salon acts. Straight from the Old Country – you’ll love it. Besides, Dr. Weiner didn’t say I couldn’t go out, he just said I had to take it easy.”

Mama beat the eggs with unnecessary vigor. “It will not make you happy, to watch someone else fly.”

“I miss the circus, you know?” Lenka got up and put an arm around her mother’s stiff shoulders. “Please, Mama? I’m going nuts, stuck here wondering if I’m ever going to be well enough to fly again.”

It wasn’t playing fair, but if Lenka had learned anything over the past year, it was that sometimes getting better involved pain.

Lenka and her parents drove in early from University Heights. As they waited for the house to open, they had time to examine the outside of the Cirque des Chauve-souris’s famous wooden tent.

“Doesn’t look like much, does it?” Mama said.

“It’s antique,” Papa said, not quite apologetically.

“So they can’t paint it? It doesn’t make a good impression, all dinged up like that.”

Papa smiled one of his sad clown smiles and took her hand. He reached for Lenka’s, too. Lenka squeezed his fingers gently and disengaged. Yes, it was painful to be waiting in line instead of making up and stretching backstage. But she’d rather he didn’t make such a thing out of it.

Inside, as her mother claimed three empty chairs on a side aisle, Lenka cast a professional eye over the setup.

The tent was roomier than it had looked from outside, but it felt cramped to Lenka, the peaked ceiling too low to fly in, the ring a raised platform hardly big enough for a decent cartwheel. A ramp connected it to a semicircular stage curtained with worn scarlet velvet. The audience was stacked back from the ring in folding chairs. A row of raised booths against the walls was furnished with tables and velvet banquettes. Above them were faded old-timey murals of circuses past. The light wasn’t great, but Lenka made out clowns in whiteface, a ringmaster in scarlet, a girl standing on a fat-haunched pony, a boy on a flying trapeze.

Lenka felt a tug on her sleeve. “They’re starting.”

The houselights snapped off; a portable steam organ struck up a wheezy oompah-pah, oompah-pah. A spot came up on a woman dressed in brown velvet with a cape to her feet. Her head was covered with a half mask sporting leaflike bat ears. The ringmistress. Battina.

She lifted her arms, and the cape hung down from her wrists like wings. “Welcome, mesdames,” she fluted, Russian accent thick as borscht. “Welcome, messieurs. Welcome. Les Chauve-souris!”

Lenka heard a chittering overhead, and suddenly the air was full of movement, half seen and half heard, a restless, leathery flutter. A woman gave a nervous shriek, and Mama covered her head protectively as small, dark shapes flickered through the lights and down to the stage. A crashing chord, and the shapes transformed into a troupe of performers, caped and masked in brown.

Mama folded her hands in her lap. “Handkerchiefs and trapdoors. They’re fast, though.”

As the organ struck up “Thunder and Blazes,” Battina rose into the air and skimmed over the ramp, her cape flaring out behind her. Everyone gasped, even Lenka. Between the cape and the tricky lighting, the telltale bulk of the harness and the glint of the wire were functionally invisible. Battina looked like she was really flying.

She circled over the audience and disappeared behind the curtains.

“Nice effect,” Mama said.

“Shh,” Papa said. “The acrobats.”

Lenka giggled.

There were three Vaulting Sokols, slender young men with white teeth and incredibly fast reflexes.

Papa watched their flipping and posturing for a moment, then whispered in Lenka’s ear. “They tumble like in your grandfather’s time – much skill, but little imagination.”

Behind Lenka, someone got up and headed for the bar. “They’re losing the audience,” Mama muttered.

The next act was better – a big man in a moth-eaten bear suit and a contortionist in a scale-patterned leotard who slithered around his body with multivertebraed suppleness until he plucked her off and spun her in the air like a living ball.

When the bear man and the snake girl removed their masks, Lenka saw that the girl was about her age, with very fair skin and very dark hair cut in a square bob. She made her compliment to the audience without a glimmer of a smile, one arm raised, her knee cocked, pivoting to acknowledge the applause.

“Very professional.” Mama approved.

The next act was Battina, capeless, and with black velvet cat ears sticking out of her thickly coiled hair. She swept in, proud as a queen, heading a procession of seven cats, their tails and heads held high.

Lenka had seen cat acts before – mostly on YouTube. Cats are cats. Even when they’re trained, they tend to wander off or roll belly-up or wash themselves. Not Battina’s cats. They walked a slack rope, jumped through hoops, balanced on a pole, and most remarkably of all, performed a kind of kitty synchronous dance routine in perfect unison, guided by Battina’s chirps and meows.

“The woman’s a witch,” Mama muttered.

“Shh,” Lenka said.

When the lights came up for intermission, Papa turned to her anxiously. “You like?”

“She’d better,” Mama said.

“The cats were way cool. And the contortionist is the bomb. Can I get a Coke at the bar? I’m really thirsty.”

After the break came a female sword swallower, a Japanese girl on a unicycle, and a slack-rope walker in a striped unitard that covered him to the knees. Lenka judged them all better than competent, but uninspired.

The contortionist reappeared, cartwheeling out between the curtains and down the runway, a simple effect made spectacular by the shimmering bat’s wings that stretched from her ankles to her wrists. Reaching the center of the ring, she reached up, grasped a previously invisible bar, and rode it slowly upward. Lenka’s throat closed in pure envy.

About six feet up, the trapeze stopped and the girl beat up to standing, bent her knees, and set the trapeze in motion, her wings rippling as she swung.

“She’s going to get those tangled in the ropes,” Mama muttered darkly.

She didn’t. Lenka watched the girl flow through her routine, twisting, coiling, somersaulting, hanging by her hands, her neck, one foot, an arm, as if the laws of gravity and physics had been suspended just for her. She must be incredibly strong. She must be incredibly disciplined. She must not have any friends, or go to movies or play video games or be on Facebook, just train and perform and sleep and do her chores and her lessons and train some more. It wasn’t a normal life. Mama and Papa said Lenka would learn to like normal life, if it turned out that she couldn’t perform.

Mama and Papa were so totally wrong. Dear Mama and Papa: When you read this, I will be far away from here.I’m not leaving because I don’t love you, or because I think you’re mean or unfair or anything. You’re the best and most loving parents in the world and you’ve saved my life, even more than Dr. Weiner and the clinic. You’ve given up a lot to make me well, and you haven’t tried to make me feel guilty about it, which is totally awesome.The thing is, I feel guilty anyway. And fenced in and tied down and fed up and generally sick and tired. And it’s not just all about me, although it probably sounds like it. I can see what my being sick has done to you. Temp work? Retail? Get real. Even Papa can’t make it funny. You’ve got to go back to flying again.Which you can’t as long as you’re looking after me.So I’m going away. Please don’t look for me. I’m eighteen. I’m in remission, I feel fine, I’ve got a little money to live on until I can find work. The only thing I’m tired of is resting. In a month or so, I’ll let you know how I’m doing. I’m going to call Radek’s cell phone, so you better be on the road.LenkaP.S. I know it’s stupid to say don’t worry, but really, you shouldn’t. You taught me how to take care of myself.P.P.S. I love you.

Lenka knew her parents. No matter what her letter said, they’d look for her, and the first place they’d look was the Cirque des Chauve-souris. She spent a couple of days hiding out, mostly in the Cleveland Art Museum, on the theory that it was the last place on Earth they’d expect her to be.

After the Cirque des Chauve-souris’s last show, she gave herself a quick sponge bath in the museum john and headed downtown.

Lenka had been hoping to slip in under cover of the mob scene that was a circus breaking down. When she found the backyard deserted, she was a little freaked out, but she didn’t let it stop her from slipping through the stage door.

A voice spoke out of the darkness. “We wondered when you’d show up.”

Lenka froze.

“Don’t worry,” the voice said. “We won’t call the police.”

“The police?”

The contortionist stepped into the light. Close up, she looked smaller and paler. “They’ve been here twice, looking for Lenka Kubatov, age eighteen, five foot six, brown-brown, hundred fifteen, kind of fragile looking. That’s you, right?”

Fragile looking? Lenka shrugged. “That’s me.”

“You ran away from home? Why? Do your parents beat you?”

“No,” Lenka said. “My parents are great.”

“Then why.?”

Lenka squared her shoulders. “I want to join the circus. This circus. I want to be a roustabout.”

The contortionist laughed. “That’s a new one,” she said. “Well, you’d better come talk to Battina.”

The ringmistress of the Chauve-souris was helping the strong man unbolt the booth partitions and banquettes from the walls. There wasn’t a roustabout in sight.

“The runaway,” she said when she saw Lenka. “Hector, I need a drink.”

The strong man laughed and slotted the partition into a padded wooden crate. “Later,” he said.

Battina settled herself on a banquette, for all the world as if she hadn’t been lifting part of it a moment before. “You must call your parents,” she said severely.

Lenka shook her head. “I’m eighteen.”

“The police said you are sick.”

“I was sick. I’m better now. I need to live my own life, let them live theirs. They’re flyers. They need to fly.”

“What was wrong with you?” Hector asked.

“Cancer,” Lenka said shortly. “Leukemia.”