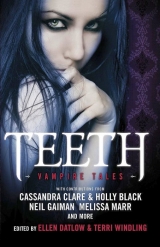

Текст книги "Teeth: Vampire Tales"

Автор книги: Neil Gaiman

Соавторы: Cassandra Clare,Catherynne M. Valente,Cecil Castellucci,Ellen Datlow,Christopher Barzak,Kathe Koja,Tanith Lee,Lucius Shepard,Jeffrey Ford,Steve Berman

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 18 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Slice of Life

by LUCIUS SHEPARD

I’ve never done it with another girl, but Sandrine gets me thinking how it would be. She’s got the kind of body I wish I had, long legged and lean, yet with enough up top to keep boys happy. Her nose is too big and beaklike for her narrow face, but after you study on her awhile, it seems to settle in above her generous mouth, becoming part of her beauty. The light that shines her into being, reflecting off God knows how many shards of mirror, makes it difficult to judge – most times she’s scarcely more than a sketch with a few hazy details – but I figure if all her color was restored, her hair would be jet-black and her eyes dark blue like the ocean out past the sandbar on a sunny day.

She says I’ll never leave her, that we’re two of a kind, and who knows, maybe she’s right.

If you’re born in these parts, in one of the sad, savage, broken towns along the St. John’s River, now reduced to cracker slums. shells of old mansions with fallen-in roofs and busted-out screens on the front porch and people inside gray as the weathered boards, moldering amid live oaks and scrub pines. Surrounded by a prefab debris of bait shops and trailer parks and concrete block roadhouses where redneck coke dealers shoot nine ball for crisp new hundreds and bored fifty-dollar hookers sit at the bar wishing for a Cadillac to bear them away on one last windy joyride. Towns like this, towns like DuBarry, Sandrine says, they stain you with their colors and make you vulnerable to their deceits. You can go to Dallas or New Orleans or somewhere they speak a foreign language, you can live there the rest of your days, but that won’t change a thing. No matter how far you travel or how long you stay, you never feel real anywhere else and you’re always living a measly cheat of a life that makes you think you’ve got to get over on folks even when you’re doing just fine playing it straight.

I’ve never been south of Daytona or west of Ocala or north of Jacksonville, so I’m no expert, but maybe Sandrine’s got a point. People who return to DuBarry after years of being away, you can see the relief in their faces, as if the pressure is off and they can’t wait to start dissolving in the heat and damp of the town, like the pigs’ feet atop the counter down at Toby’s, mutating in their jar of greenish brine.

Take Chandler Mason.

After graduating from FSU she headed for New York, where she hired on at ESPN. She started out reading the news on one of their sports talk shows and before long she landed a job as a sideline reporter for NBA games; then, a few years later, suddenly, with no reason given, she was back in DuBarry, strutting her stuff in designer clothes. Whenever she strolled by, the men sitting in rusted lawn chairs out front of Toby’s would develop a case of whiplash. Following a whirlwind courtship, she married Les Staggers, an ex-marine who teaches phys ed and algebra at County Day, and popped out three kids, put on fifty, sixty pounds, and now when she passes, the men in the lawn chairs say something like “Must be time to water the elephants,” and share a big laugh. She goes on a liquor run a couple of times a week, weaving an unsteady path to the ABC store, wrapped in a cloud of diaper stink, and on Sundays she accompanies Les to Jacksonville Beach, where he’s a deacon in some screech-and-holler church. Otherwise she stays home with the blinds drawn and her brats yowling, drinking gin-and-Frescas, the TV on loud enough to drown out the twenty-first century.

Sandrine says that’s the best I can hope for, unless I help her, unless she helps me, and I can probably expect a whole lot worse, considering my reputation.

– Go fuck yourself, I tell her.

– That’s all I ever do, says Sandrine.

This matter of my reputation has come under fire from predictable quarters. Boys who I won’t let touch me write my name on bathroom walls and talk about the things I’ve done with them, things they’ve only heard about. They go to singing “Louie, Louie” whenever they see me coming. Louie’s short for Louise – it got tacked on me in grade school for being a tomboy, and ever since they started with that dumb song, I’ve been trying to convince my friends to shorten it further and call me Elle. Not that the singing bothers me so much. but it’s annoying and I think Elle’s a name I’ll grow into someday. Old habits die hard, though. I expect I’ll be stuck with Louie for as long as I hang around DuBarry.

Momma told me once that the tales people carry about me make her cry herself to sleep.

– Excuse me, I said. I sleep right across the hall and what I hear coming from your room don’t sound a thing like crying. What it sounds like is you and Bobby Denbo bumping uglies. Or else it’s Craig Settlemyre. I can’t keep those two straight.

– I’m a grown woman! I’ve got the right to a life!

– Some life, I said.

My faculty advisor at County Day, Judy Jenrette, has expressed sincere concern that my promiscuity is an outgrowth of low self-esteem. I tried to nip this concern in the bud by assuring her that my self-esteem was just dandy, but judging by the way she pressed her lips together, her chin wobbling, I suspected that she thought to see her younger self in me and was repressing an Awful Secret that tormented her to this day. Before I could prevent it, she unburdened herself of a dismal story about teen pregnancy and its consequences that I must have watched half a dozen times on Lifetime Television for Women, only this came without the hot guys.

– I appreciate you letting me hear that, I said. I honestly do.

Judy snuffled, dabbed her eye with a tissue, and forced a shaky smile.

– That story don’t apply to me, though, I said. We’re different breeds of cat. You were in love. Me, I fuck because I’m bored. And living here, if I’m awake I’m bored.

– Language, Louie!

– I’m taking birth control and no one gets near me without a condom. If I got pregnant, you better believe Momma would drag me to the clinic and sign those abortion papers. Having me around is bad enough for her love life. A baby would just about finish her off.

Judy said that pregnancy wasn’t her only worry, that sexing it up so young would cause me to have emotional issues. She handed me a pamphlet on Teen Celibacy with a photo on the front of cheerleader types who appeared to be overjoyed by not getting any. I read enough of the pamphlet to get the basics – if you saved yourself for marriage Jesus would love you, Coke would taste better, etc. – and then Googled the company that produced it. They turned out to be the subsidiary of a corporation that made its mark selling baked goods. This led me to speculate that doing without caused you to eat more cupcakes and that a generation of diabetic Teen Celibates were victims of a duplicitous marketing campaign. Who knew there was profit to be had from negative pimping?

Where Sandrine lives is off a blue highway a couple of miles south of DuBarry, a tore-down, two-room fishing shack tucked into a hollow on the riverbank, camouflaged by ferns and fallen beards of Spanish moss, hidden by chokecherry bushes and a toppled oak out front. You’d never spot it unless you were looking for it, and you wouldn’t go near it unless you’d lost your mind. What’s left of the place is roofless, crazy with spiderwebs and rotting boards so crumbly you can rip off pieces with your hands. If you go inside, you’ll find that every inch of the walls and part of the floor is covered with glued-on shards of mirror, and if you trespass on a night during a period between three days either side of the full moon, chances are you won’t be coming out again. Sandrine can’t compel you like once she could, but she’s got enough left to slow you down. You’ll see her stepping to you and you’ll stumble back in fright, even though you’re not sure she’s real, and then you see the hungry glamour in her eyes, and that holds you for a second.

A second’s all it takes.

She won’t talk much about the past – she prefers to hear about my life, a life I’d gladly leave behind. Some nights, though, I get her going and she tells me things like she was born in 1887 in Salt Harvest, Louisiana, a little Acadian town, and was turned when she was twenty-three by a fang who left her to figure out on her own what she’d become. She’s been living in the shack since 1971, sustaining herself on whatever animals happen along. Frogs, mainly. She hardly ever supplies much detail, but we were sitting on the toppled oak one night, right at the boundary beyond which she cannot pass, watching the water hyacinths that carpet the majority of the river undulate with the current, their stiff, glossy green leaves slopping against the bank, and I asked how she’d come to be stranded there. She had just fed and was more substantial than usual, yet I could see low stars through her flesh and, when she shifted position, the neon lights of a roadhouse on the opposite bank. Sweet rot merged with the dank river smell, creating an odor that reminded me of the rained-on mattress in Freddy Swift’s backyard.

– Djadadjii, Sandrine said. I’ve heard them called other names, but that’s what Roy called them. He’s this fang I traveled with in ’71. and for a while before that.

– What’s jajagee?

– Not jajagee. Djadadjii.

Mosquitoes plagued us, but Sandrine didn’t seem bothered. She looked off south toward the roadhouse.

– They look like humans, but they’re not – they mimic humans. Roy heard that this old Jewish magician bred them in the seventeenth century to hunt fangs. They’re stronger than fangs and they can do one piece of magic. That’s what binds me here. Why I’m like this. The Djadadj that ate Roy, he couldn’t eat anymore, so he salted me away for later.

– And left you here forty years?

– Maybe he got hit by a bus. Or maybe he forgot. They’re not very smart. But sooner or later, he’ll remember where he stored me, or else another one will sniff me out.

She nailed me with a stare I felt at the back of my skull. That’s the best can happen unless you help me, she said.

– Do we have to talk about this every time I come out? I’m thinking about it, okay?

She kept staring for several seconds and then sighed in dismay.

– It’s not the easiest thing to wrap your head around, I said. Becoming a serial killer.

– I do the killing.

– Yeah, but I have to lure them here. That’s even more disgusting.

– Listen, Louie. I.

– Elle!

– I’m sorry. Elle.

A distant plop came from the center of the river, where there was open water.

– I only need five, she said.

– I know what you need. It’s not like you never tell me.

– One a night for five nights. Then I’ll be strong enough to break free. There must be five people you hate in town. Five like that first one.

– You have to give me more time.

We sat quietly, caught in our bad mood like two flies in a puddle of grease. I thought to say I had to go, but I didn’t want to go. Sandrine wrestled with a hyacinth stem and snapped off a lavender bloom and offered it to me. When I accepted it, her fingers brushed mine and I felt a blush of heat, like I’d rubbed my fingertips fast over a rough surface.

– Does Djadadjii magic work on regular people? I asked.

– No. They don’t care about you, anyway. They’re only interested in fangs.

– Suppose you get clear of this. What’ll you do?

– Maybe South Carolina. There’s a group of fangs there who’re well protected. They’re not fond of outsiders, but I’m tired of being on my own. It might be worth the risk.

– What if you weren’t on your own?

– If you were with me, you mean?

I shrugged. Yeah.

– I’d probably stay here.

That alarmed me. In DuBarry?

– No, no. Florida. Most of the fangs in this hemisphere are in Latin America and.

– How come?

– It’s easier to get away with killing there. Of course it’s a trade-off. Since most fangs are there, most of the Djadadjii are, too. The one that caught me, he’s only the fourth I’ve seen up here. and the first three were over a century ago.

A bug crawled from beneath a petal of the bloom Sandrine had plucked, and I laid it on the oak trunk.

– You all right, cher?

– Tell me some more about the Djadadjii.

– I don’t know much more. They all have wide mouths. Their mouths expand. They could swallow a football if they wanted. They could bite it in half. And they have a refined sense of smell. If a fang’s been near you, they’ll pick up the scent. Roy told me they’re all beautiful and the ones I’ve known were beautiful. and dumb. Dumb as chickens.

A fisher bird swooped low above the hyacinth, and the faint chugging of a generator came from somewhere upriver.

– Take off your top for me, said Sandrine.

– I. I don’t.

– I won’t touch you. I know you’re shy and you’re not ready, but I want to look at you this once. She pretended to pout. It’s not fair you can see me and I never see you.

Hesitantly, I reached back and undid the strings of my halter. I fitted my eyes to the red winking light atop a water tower across the river and held the halter in place for a second; then I let it fall.

– God, she said. I’d forgotten.

– What is it? I asked. Is.

Shh! She reached down to the river and cupped her hand and scooped up some water and let it trickle between her fingers onto my breasts. Cool and lovely, little rivers spilling over my contours. I felt beautiful and grand, a hill divided by tributaries. My skin pebbled where the water touched me. One nipple poked up hard.

The halter slid off my lap. Sandrine handed it to me and told me I could put it back on.

– No, it’s okay. My hair curtained my face, hiding my excitement. It’s nice. sitting here like this.

One afternoon when I was fifteen and feeling downhearted, I hitched out to the old boneyard set in a fringe of Florida jungle south of town and sat beside the big gray angel, drinking from a pint of lime-flavored vodka I’d lifted from Momma’s stash. Forty years ago a bunch of DuBarry kids went skinny-dipping at night in the ocean near St. Augustine. Their bodies were never found (it’s assumed they were caught in a riptide) and the town put up the angel beneath a twisted water oak for a memorial. They must have skimped on the sculptor, or else they were going for something different. or maybe getting vandalized four or five times a year has taken a toll, because except for more-or-less regulation wings, it resembles the husk of a half-human female insect nine feet high. The grave tenders have gotten slack about scraping paint off it, and the statue has acquired a crusty glaze over the head and torso that makes it look even weirder. Used to be there were some goth kids who lit candles and sang to the angel, but that provided an evangelical preacher with an excuse to rev up his campaign against devil worship and their parents smacked the goth out of them. Now kids come there to bust bottles on the headstone and howl and dry heave and screw, and I guess some believe they gain power over death by pissing on the angel or smearing it with paint, behavior the town apparently deems more in keeping with the moral standard.

I got pretty smashed and lay on my back, thoughts drifting from one depressing topic to the next, watching the dusk and then darkness settle in the oak boughs. A car purred along the dirt drive, its engine so quiet I heard the tires crunching gravel. Headlights swept over me. I figured it for kids and didn’t pay any attention. Someone came to stand above me – the salesman who had given me a ride out, a chunky middle-aged bald guy in a madras jacket.

– You still here? he asked.

– Naw, I said, wondering foggily what he was doing there – he’d told me he had stops to make in Hastings and Palatka.

He toed the empty vodka bottle and then stuck out a hand. Come on. I’ll ride you into town. This ain’t no fit place for a young lady.

Calling me a young lady must have pushed my daddy button, because I let him haul me to my feet. He had doused himself with cologne, but I could smell his sweat. He pulled me close and ran a hand along my butt and said thickly, Man, you are one sweet-looking piece of chicken.

I started to freeze up but recalled Momma’s advice.

– There’s a motel down near Orange Park that don’t ask no questions, I said.

I didn’t think he bought my act. He held me tightly and seemed confused; then a smile split his doughy face.

– Damn! he said. I was halfway to Hastings before I realized you were putting out signals.

All I’d done in his car was not look at him and grunt answers to his questions. He gave my breast a squeeze and I rubbed against him and said in a breathy voice, Ooh, yeah!

– You like that, huh? he said.

With my free hand I hiked up my T-shirt, exposing the other breast. He played with it until the nipple stiffened, then grinned like he was the only one who could work that trick.

– I been watching you for must be an hour and a half, he said. Here we could have been having some fun.

He placed his hand on the small of my back, the way you’d squire a prom date, and steered me toward his car – a crouching animal with low-beam eyes. I broke free and kneed him in the crotch. He puked up a groan, grabbed his jewels, and bent double. A string of drool silvered by the headlights unreeled from his lips. He went down on all fours, breathing heavy, and I kicked him in the side. That’s where I departed from Momma’s plan of action. Instead of running like hell, I grabbed the vodka bottle and busted out the bottom on a headstone and told him if he didn’t get the fuck gone I’d slice him. He came at me in a clumsy run, a hairless bear in a loud sport jacket, cursing and reaching for me with clawed hands. I slashed his palm open and lit out for the trees, leaving him screaming in the dirt.

For a time I heard him shouting and battering through the underbrush. I moved away from the noise and tried to circle behind him but lost my bearings. After hiding for half an hour or so, I thought he must have given up. A big lopsided moon was on the rise and I could smell the river but had no other clue as to where I stood in relation to the graveyard. I located the river and trudged along the bank, detouring around thickets, figuring I’d head north until I recognized a landmark. Crickets sizzled, frogs belched out loopy noises, and beams of moonlight chuted down through the canopy, transforming the bank into a chaos of vegetable shapes spread out across the irregular black-and-white sections of a schizophrenic’s checkerboard.

If I hadn’t cut him, I told myself, he would have probably slunk away. It don’t do to piss off that kind more than you have to, Momma said. Otherwise they’re liable to get obsessed.

I pushed back a palmetto frond, ducked under it, and stopped dead. The salesman stood about forty feet away in a slash of moonlight, thigh deep in weeds and gazing out across the river with a pensive air, as if he were rethinking his goals in life. He’d shed his jacket and was shirtless – the shirt was wrapped around his left hand, the hand I’d sliced. A thin shelf of flab overhung his belt.

I retreated a step, letting the frond ease back into place, and he looked straight at me. I could have sworn he didn’t see me, that he had simply caught movement at the corner of his eye and been put on the alert. Then he sprinted toward me. I ran a few steps and pitched forward down a defile, gonging my head pretty good. Dazed, I realized I’d fetched up among ferns sprouting beside an abandoned shack. The door hanging one-hinged. Roofless. The moon shone down into it, but the light inside was too intense for ordinary moonlight – it cast shadows that looked deep as graves and flowed like quicksilver along spiderwebs spanning broken windows and gapped boards. Shards of mirror covered the interior walls, reminding me of those jigsaw puzzles that are one color and every piece almost the same shape. I picked myself up and was transfixed by the image of a bloody terrified girl reflected in the mirror fragments.

– Bitch!

The salesman spun me around, gut-punched me, and slung me through the door. Next I knew he had me straddled, pinning my arms with his knees and fumbling one-handed with his zipper, telling me what he had planned for the rest of our evening. When I made to buck him off, he slammed my head against the floor. He gaped at something behind me and I rolled my eyes back, wanting to know what had distracted him.

A ghost.

That was my first thought, but she had more the look of animation, a figure with just enough lines to suggest a naked woman, her colors not filled in.

The salesman scrambled to his feet, and she seemed to flow around him like a boa constrictor, locking him into an embrace and drawing him toward the back room, where they vanished, slipping through a seam that opened in midair and then closed behind them, leaving no trace. I don’t believe he made a single sound.

I had a strong desire to leave and got to my knees, but the effort cost me and I blacked out. When I came to, I heard her humming an aimless tune. I slitted my eyes and had a peek. She sat cross-legged by my side. She was more defined and her colors were brighter, though they were still ashen. except for a single drop of blood below her collarbone. She smiled, exposing the points of her fangs. I scooted away from her, but she had me and I knew it.

– Don’t fret, cher, she said. I won’t hurt you.

She noticed the blood drop, touched her finger to it, and licked the tip clean. I was too scared to speak.

– That man, she said. You’re safe from him now.

My head had started to clear and I felt the creep of hysteria. Is he dead?

– Not dead. He’s. waiting for me.

– Where is he? What’s going on?

– He’s where I sleep. Go slow, now. Calm yourself and I’ll tell you all about it.

Just her saying that had an effect on me – it was like she’d turned down my temperature.

– I’m Sandrine, she said. And you are.?

– Louie.

She repeated the name, pronouncing it like she was giving it a long, slow lick.

– If you want to go, I won’t stop you, but it’s been such a long time since I had someone to talk to. Sit with me? For a little while?

I didn’t have any run left and I felt drowsy, scattered. My eyes skated across the mirror pieces. In each of them was Sandrine’s face – pensive, fearful, frowning, in repose, moving as if alive. Hundreds of Sandrines, almost all of her, were trapped in those fragmented silver surfaces.

I must have spoken, because Sandrine laughed and said, I’ve been talking to them forty years and they haven’t answered yet. For a pretty girl like you, though, they might just whisper a little something.

Cracker Paradise lies about four miles east of DuBarry on State Road 17 and consists of a spacious one-story structure of navy blue concrete block set on a weedy patch of white sand that’s round as a bald spot and surrounded by slash pine. It doesn’t sport a huge neon sign like some roadhouses, just a little plastic MILLER HIGH LIFE sign above the door, and it has a slit window that’s been painted over so you can’t see in. When I was younger, Momma would leave me locked in the car while she partied, assuming glass would protect me from the men who peered in. I used to create fantasies about the place based on glimpses I had of the interior when the door swung open. Even today, now I’ve been inside a few times, it remains a kind of fantasy. I’ll hang out in the parking lot, sipping on a wine cooler slipped me by one of Momma’s friends, and picture slinky waitress queens dancing barefoot on sizzling short-order grills and serving slices of fried poison to travelers in bathroom fixtures, while out on the purple-lit bash and rumble of the dance floor, checkout girls from the Piggly Wiggly, acne-blemished counter girls from Buy-Rite, pretty-for-a-season Walmart girls with clownish face paint and last decade’s hairdo, they shake themselves into a low-grade fever, they make suggestions with their hips that turn the loose change in men’s pockets green, they slice hearts and pentagrams on the beer-slickered floor with their spike heels, looking to give it up for love-only-love and a cute duplex in Jax Beach.

A few nights ago, a hot July night with the moon causing the sand to give off sparkles and silvering the hoods of the cars encircling the club, and a couple of hundred rednecks jammed inside, I stood in the parking lot smoking with two girls from New Jersey, Ann Jeanette and Carmen, who intended to compete in the wet T-shirt contest later that night. They were good-looking, gum-snapping, tough-talking girls in their early twenties, with frosted hair and big boobs, and they wore bikini thongs and Cracker Paradise Tshirts. They told me they were on the run from Ann Jeanette’s boyfriend, who was connected and owned a recycling company in East Orange. Both girls were secretaries with the company, and they had stumbled across some paperwork they weren’t supposed to see. The boyfriend ratted them out to a Mafia guy, and they had to leave town in a hurry. Since then they’d worked their way down the East Coast, heading for Miami, where Carmen had friends, entering wet T-shirt contests to pay for a few months out of the country. They claimed to win most of the contests they entered and considered themselves pros on the circuit.

Carmen nudged my breasts and said, You should enter, hon. They’re paying out to fifth place.

I told her I was sixteen.

– Sixteen! My gawd! Ann Jeanette flicked ash from her Kool – her fake nails were gold with tiny black diamonds. You’re very mature for sixteen. Don’tcha think she’s mature, Carmen?

– Extremely, Carmen said. You gotta watch it with a figure like yours. Ann Jeanette’s little sister was wearing a C cup in junior high and by the time she’s your age, she needed a reduction.

– I’ll be seventeen soon, I said. I don’t think they’re going to get much bigger.

– Oh my gawd! Ann Jeanette rolled her eyes.

– All the women in her family are big, said Carmen. You should see her mutha. The poor creetcha! Believe me, hon. They can get a lot bigger.

Two high school boys leaned against the bed of a pickup farther along the row, watching us. When they started singing “Louie Louie,” Ann Jeanette took note of my embarrassment. She strolled over to the pickup and talked to them for half a minute. By the time she came back, they had hopped into their truck and were trying to start the engine.

– What’d you say? I asked delightedly.

– Fucking winkie dicks, she said.

Carmen gave her a hug and kissed her cheek and said, Ann Jeanette’s badass!

– I hate fucking winkie dicks. Ann Jeanette inspected her nails and appeared satisfied. Men suck! It’s true, they can be stimulating, but most of ’em are winkie dicks.

– We should go in, Carmen said. That guy runs the contest is a real pisser. We could lose our spot.

– The scrawny bitches they got in there, they can’t afford to lose us. Now if Louie here were competing, we’d be in trouble. Ann Jeanette planted a sloppy kiss on my mouth, startling me, and said, Maybe we’ll see ya after, doll.

They fluttered their hands in a wave and walked away arm in arm, wobbly in their high heels on the uneven ground.

I hopped up on the fender of a car and shut my eyes and thought about Sandrine. She’d be angry at me for not visiting her, but I was sick of being pressured and thought that when I visited her tomorrow night, the pressure would be off – no way I could bring her five live bodies in the next couple of days, so she wouldn’t pester me about it and we could relax. I heard a blast of music and crowd noise as the door opened and looked in time to see it swing shut. This blond guy had stalled in midstride outside the door and was staring at me. After a second he came over. He was too old for me, twentysomething, but he was way beyond cute. He had blue eyes with long pale lashes, and his mouth was so wide and beautifully shaped I wanted to touch it, to make certain it was real. He was almost pretty, like a gay guy, but he didn’t have that vibe. I thought I might expand my age limit for him. When he leaned against the fender, I felt the temperature go up a notch.

– I like the way you smell, he said.

– That’s because I shower regularly.

He nodded soberly, as if a daily course of hygiene was an intriguing concept, something he might one day consider. His conversational skills seemed limited, but I figured he was nervous, so I said, What do you mean, I smell nice? Do I smell springtime clean or minty fresh or what?

He appeared to struggle with the question.

– Where you from? I asked.

– Up north, he said. I have a job.

I scrunched around, brushing his arm with my hip. His skin was hot, but he wasn’t sweating.

– Is your job with the CIA? I asked. That’s why you’re being circumspect? Because you’re a spy and you’ve been trained to guard against the likes of me?

His mouth hung open – I thought his circuits might be fried. To test my theory, I asked his name.

– Johnny, he said. Johnny Jacks.

The notion of doing a moron with a retarded name like Johnny Jacks. it didn’t sit well. The last guy I’d gone with on the basis of his looks alone lay there afterward, thumping the side of my breast again and again, laughing to see it jiggle.

– Well, Johnny. I slid off the fender. I’ll catch you later.

He started to follow me toward the door, and I turned on him and yelled, Stay! Sit! Don’t follow me, okay?

I opened the door a crack and asked Wayne the bouncer if he cared to join me for a smoke and help fend off someone annoying. Wayne said, It’s too damn hot. You can sit inside.

The AC made me happy – my sweat beads popped like champagne bubbles. Ted Horton, the radio deejay who oversees the wet T-shirt contests, did his spiel, the microphone blatting and squealing. The crowd whistled and yelled. Wayne wouldn’t let me peek around the corner at the stage, and all I got to see were the geezers shooting pool at the rear. I played with Wayne’s ink stamp, pressing it to my wrists, imprinting several dozen blurry Cracker Paradise logos. He scowled and snatched it away. Ted announced the winners – I couldn’t make out the names – and the crowd turned ugly. They cursed Ted and he cursed them. “Fuck you” were the first words of his I heard clearly. Wayne shoved me back out into the heat.