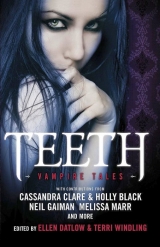

Текст книги "Teeth: Vampire Tales"

Автор книги: Neil Gaiman

Соавторы: Cassandra Clare,Catherynne M. Valente,Cecil Castellucci,Ellen Datlow,Christopher Barzak,Kathe Koja,Tanith Lee,Lucius Shepard,Jeffrey Ford,Steve Berman

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 22 страниц)

Sebastian had his eyes open while he kissed Nikki, watching as Eliana bit the girl.

It wasn’t disgusting. Well, it was, but not in a rather-die-than-eat way. It was instinct. Like any animal, Eliana hungered, and so she ate.

She didn’t gorge, didn’t kill the girl, but she swallowed the blood until she felt stronger. If a bit tipsy. The buzz that she got from drinking the girl’s blood was somewhere between a good high and a delicious meal. Familiar. The taste wasn’t new. His blood was better.

Eliana let the girl fall to the floor and looked at him.

Sebastian and Nikki were all over each other. Nikki had pushed him against the wall, leaving her back to Eliana, and he was cupping the back of Nikki’s head with one hand. His other hand was on the small of her back.

“Nicole,” he murmured. He kissed her collarbone. Without pausing in his affections, he lifted his gaze and looked at Eliana.

The temptation to rip Nikki out of his arms was sudden and violent. It was irrational and ugly and utterly exciting. All she wanted was to tear out the other vampire’s throat, not to feed, not carefully. Like she did to Gory. Eliana couldn’t: In a fair fight, Nikki would kill Eliana.

She felt her teeth cutting into her lip and opened her mouth on a snarl.

She stepped forward. Her hands were curled in fists.

Fists aren’t enough.

“I need” – she looked at Sebastian – “help.”

Sebastian spun so Nikki was now the one against the wall, with his body pressed against her. With one hand he caught her wrist and held it to the wall.

Nikki looked past him to Eliana. “For centuries he’s been mine. A few weeks of being with you is nothing.”

“Two months,” he murmured as he raised Nikki’s other wrist so he was holding them both in his grasp.

Then he kissed her, and she let her eyes close.

Sebastian reached back and lifted the bottom of his shirt. In a worn leather sheath against his spine, there was a knife.

Eliana walked toward it and wrapped her hands around the hilt of the knife.

She stood there, her knuckles against his skin.

He made me this. He knew she’d murder me. Eliana remembered the blood and the kisses. He’d picked her, changed her life. But Nikki suffocated me.

Eliana wanted to kill them both. She couldn’t, though; even if he gave her access to his throat, she couldn’t raise a hand to him. She wasn’t sure why, but she couldn’t do it.

And with his help, I can kill Nikki.

With a growl, Eliana stabbed the knife into Nikki’s throat.

Sebastian held Nikki up, his body still pressed against her, and kissed her as she struggled. He swallowed her screams, so no one heard.

Then he pulled back. He held out his arm, and Eliana moved closer. She reached up and covered Nikki’s mouth with her hand, just as Nikki had done to her.

“Go ahead,” he whispered.

Eliana closed her mouth over the wound in Nikki’s throat and swallowed. Her blood was different from the human girl’s blood; it was richer.

Like Sebastian’s.

Nikki struggled, but Sebastian held her still. He held them both in his embrace while Eliana drank from her murderer’s throat. For more than a minute, they stayed like that. The sounds of drinking and soft struggles were covered by the noise downstairs.

Then Nikki stopped fighting, and Eliana pulled back.

Sebastian let her go, and he sat on the bed, cradling Nikki in his arms while he drank from the now motionless vampire. If not for the fact that she was staring glassy-eyed at nothing and her arm dangled limply, it would almost have seemed tender.

Sebastian wrapped the scarf that he’d brought with him around her throat to hide her wound. Then he and Eliana washed Nicole’s blood from their faces and hands. They stood side by side in the adjoining bathroom.

Back in the bedroom, he slipped a few trinkets into his pockets and grabbed a messenger bag from the closet. Eliana said nothing. She hadn’t spoken since before Nicole’s death.

“There are clothes in the closet that would fit you,” he suggested.

She changed in silence.

He took the bloodied clothes and shoved them into the bag, lifted Nicole into his arms, positioned her head, and carried her as he had done earlier. In silence, they walked downstairs and out the door. A few people watched drunkenly, but most everyone was too busy getting lost in either a body or a drink.

Eliana was more disturbed by murdering Nikki than she had been by being murdered by her – mostly because she’d enjoyed killing Nikki.

She closed the door to the house behind her. For a moment, she paused. Can I run? She didn’t know where she’d go, didn’t know anything about what she was – other than dead and monstrous. Are there limitations? There were two ways to find out if the television and book versions of vampire weaknesses were true: test them or ask.

Instead of following Sebastian, she sped up and walked beside him. “Will you answer questions?”

“Some.” He smiled. “If you stay.”

She nodded. It wasn’t anything other than what she expected, not after tonight. She walked through the streets in the remaining dark, headed back to the graveyard where she’d been murdered, escorting the corpse that she’d murdered.

Inside the graveyard, they walked to the far bottom of the hill, in the back where the oldest graves were.

Sebastian lowered Nikki to the ground in the middle of a dirt-and-gravel road in the far back of a graveyard. “Crossroads matter, Eliana.”

He pulled a long, thin blade from Nikki’s boot and slit open her stomach. He reached his whole forearm inside the body. His other hand, the one holding the knife, pressed down on Nikki’s chest, holding her still. “Until this moment, she could recover.”

Eliana said nothing, did nothing.

“But hearts matter.” He pulled his arm out, a red slippery thing in his grasp.

He tossed it to Eliana.

“That needs buried in sanctified ground, and she” – he stood, pulled off his shirt, and wiped Nicole’s blood from his arm and hand – “needs to be left at crossroad.”

Afraid that it would fall, Eliana clutched the heart in both hands. It didn’t matter, not really, but she didn’t want to drop it in the dirt. Which is where we will put it. But burying it seemed different than letting it fall on the dirt road.

Sebastian slipped something than his pocket, pried open Nikki’s mouth, and inserted it between her lips. “Wafers, holy objects of any faith, put these in the mouth. Once we used to stitch the mouth shut, too, but these days that attracts too much attention.”

“And dead bodies with missing hearts don’t?”

“They do.” He lifted one shoulder in a small shrug.

Eliana tore her gaze from the heart in her hands and asked, “But?”

“You need to know the ways to keep the dead from waking again, and I’m feeling sentimental.” He walked back toward the crypt where the rest of their clothes were, leaving her the choice to follow him or leave.

She followed him, carrying Nikki’s heart carefully.

“Killing on full or new moon matters,” he added when she caught up with him.

She nodded. The things he was telling her mattered, and she wanted to be attentive to them, but she’d just killed a person.

With his help. because of him. like an animal.

And now he was standing there shirtless and bloodied.

Is it because I slept with him? She listened to the words he said now, trying to remember the words he’d said then. Those words mattered, too. He planned this. He knew she’d kill me. He watched.

“She killed me under the full moon,” Eliana said.

“Yes.” He wrapped Nicole’s heart in his shirt. “You were born again with blood and moonlight.”

“Why?”

“Some animals are territorial, Eliana.” He looked at her then, and it was like stepping into her own memories. That was the same look he’d given her when she’d first gone with him, when she’d been alive and bored: It was a look that said she mattered, that she was the most important thing in his world.

And I am now.

He was looking at her the way Nikki had watched him. He brushed her hair away from her face. “We are territorial, so when we touch another, our partners respond poorly.”

“Why were you with me then? You knew that. ” She couldn’t finish the sentence.

“She’d kill you?” He shrugged again, but he didn’t step away to give her more room. “Yes, when she found you, when I was ready.”

“You meant for her to kill me?” Eliana put both hands on his chest as she stared up at him.

“It was preferable that she do it,” he said. “I planned very carefully. I picked you.”

“You picked me,” she echoed. “You picked me to be murdered.”

“To be changed.” Sebastian cupped her chin in his hand and tilted her head up to meet his gaze. “I needed you, Eliana. Mortals aren’t strong enough to kill us, and we can’t strike the one whose blood made us. The one whose blood runs inside us is safe from our anger. You can’t strike me. I couldn’t strike her.”

“You wanted her to find me and kill me, so I would kill her for you?” Eliana clarified. She felt like she was going to be sick. She’d been used. She had killed for him, been killed for him.

“I was tired of Nicole, but it was more than that.” He wrapped his arms around her waist and held tight as she tried to pull away. “We still need the same nutrients that we needed as humans, but our bodies can no longer extract them from solid food. So we take the blood from those who can extract the nutrients.”

“Humans.”

He nodded once. “We don’t need that much, and the shock and pain makes most people forget us. It hurts, you know, ripping holes in people’s skin.”

She dropped a hand to her leg in suddenly remembered pain. It did hurt. Her entire thigh had been bruised afterward. And her chest. At the time, she couldn’t remember what the bruises were from. And the bend of her arm.

He kissed her throat, softly, the way she’d fantasized about afterward when she’d believed it was just a dream, when headaches kept her from remembering more.

“Why?” she asked again. “You needed a meal and a murderer. That didn’t mean you needed to screw me.”

“Oh, but I did. I needed you.” His breath wasn’t warm on her throat; it was a damp breeze that shouldn’t be appealing. “The living are so warm. and you were perfect. There were others, but I didn’t keep them. I was careful with you.”

She remembered him looking at her and asking permission.

“Sometimes I can’t help but want to be inside humans, but I won’t keep them. We’re together now.” He kissed her throat, not at her pulse, but where her neck met her shoulder. “I chose you.”

Eliana didn’t move away.

“Nikki found out, though.” He sighed the words.

“So she killed me.” Eliana stepped backward, out of his embrace.

Sebastian had an unreadable expression as he caught and held her gaze. “Of course. Would you do any differently?”

“I. ”

“If I left you tonight and sank into some girl – or guy – would you forgive me?” He reached out and entwined his fingers with hers. “Would you mind if I kissed someone else the way I kiss you? If I knelt at their feet and asked permission to – ”

“Yes.” She squeezed his hand until she saw him wince. “Yes.”

He nodded. “As I said, territorial.”

Eliana shook her head. “So that’s it? We kill, but not under full or new moon. We drink blood, but really not so much. If we do kill, it’s some sort of territorial bullshit.”

“An area can support only so many predators. I have you, and you have me.”

“So I killed Nicole, and now you’re my mate?” She wasn’t sure whether she was excited or disgusted.

Or both.

Sebastian whispered, “Until one of us makes someone alert enough and strong enough to kill the other, yes.”

She pulled her hand out of his. “Yeah? So how do I do that?”

Sebastian had her pinned against the crypt wall before she could blink.

“I’m not telling you that, Eliana. That’s part of the game.” He rested his forehead against hers in a mockery of tenderness.

She looked at the floor of the crypt where Nicole’s heart had fallen. The bloodied shirt lay in the thin layer of soil that covered the cracked cement floor. Moss decorated the sides where the dampness had seeped into the small building.

Transition. Eliana felt an echo of herself crying out, but the person she’d been was dead.

She looked at Sebastian and smiled. A game? She might not be able to kill him yet, but she’d figure it out. She’d find someone to help her – and unlike Sebastian, she wouldn’t be arrogant enough to leave the vampire she made alive to plot her death.

Until then.

With a warm smile, she wrapped her arms around him. “I’m hungry again. Take me out to dinner? Or” – she tilted her head to look up at him – “let’s find somewhere less depressing to live? Or both?”

“With pleasure.” He looked at her with the same desperation Eliana had seen in Nikki’s gaze when she watched Sebastian.

Which is useful.

Eliana pulled him down for a kiss – and almost wished she didn’t need to kill him.

Almost.

History

by ELLEN KUSHNER

“You just totally ran that red light,” she says, not without admiration.

“I know.” As always, he sounds smug. He downshifts and passes a van that has been in front of them for blocks. “I love driving.”

He is much too old for her, but that doesn’t bother her. She has never been fussy about age. She is a historian – almost. Just a couple more papers, and she’ll get honors this year from their country’s oldest university. What bothers her is that he won’t tell her about history. “I forget,” he says when pressed. “It was all a long time ago.”

He knows. She knows he knows. He just won’t say.

“Why do you still drive shift?” she asks crabbily.

“Everyone should drive shift. Can’t you drive shift?”

“Of course I can. I just wouldn’t in city traffic, if I didn’t have to.”

He is now weaving his way through a densely populated open square ringed by ancient buildings, where the traffic vies for road space with students late for class – brilliant adolescents who believe all cars will stop for them – and with beggars and tourists and absentminded faculty. When he first knew it, the square, it was full of students in black robes and muddy shoes, never looking straight ahead of them but always up for tavern signs, or down to avoid horse manure and rotting cabbage and the occasional peasant. These students don’t look down, and they don’t look up much, either.

“Out of my way, asshole!” he growls at a blond waif with a backpack who has just stepped off the curb to wait for the light.

He loves to drive, and he loves to swear. In his youth he did neither. But that was a long time ago.

He also loves rock and roll. And the blues. “American blues,” he says. “There’s nothing like them. Muddy Waters taught Eric Clapton all he knows.”

“Have you ever been to America?” she asks.

“Once.” He scowls. “I hated it.”

She has learned not to make jokes about his needing his Native Soil. He really hates that. She’ll do it to get a rise out of him, but that’s all.

She tries to catch him when he’s half awake. “Tell me about the Great War,” she’ll say, but he turns over, muttering, “Which one?” or “They were all great.”

“Which was your favorite, then?”

“The one with the little short guy on the horse. There he was, looking out over the plain at the smoldering campfires below at what remained of his army. They were a ragtag lot. The sun was low. He turned to the adjutant next to him and said softly, ‘My friend – ’”

She whacks him on the head with her bookmark. “I saw that movie, too.”

They take a walk down by the river that runs through the heart of the city. People are lined up on the sidewalk along the bridge trying to sell them things: bead earrings, knockoff purses, used comics, watercolors of the cathedral. There’s a caricaturist drawing portraits. Her lover does reflect in mirrors, but she has the sudden thought that he would not show up in caricature. What would a cartoon sketch of him look like? The things that make him most himself are not visible to the eye. She sneaks a peek off to the side, where he stands looking at the cathedral. Long, bony nose, high brow, hair swept back. Another thought strikes her.

“Did you ever have your portrait done?”

“I – ” If he says “I forget” again, she’ll smack him. But a shadowy look passes across his face.

He did. People have drawn him, sketched him, even painted him. Maybe a student in a garret did a quick charcoal sketch of him asleep. Maybe a girl sitting in a garden somewhere tried to capture him in watercolors, a parasol shading her face.

He’s waited too long. He knows she knows. He doesn’t answer. He points at one of the knockoff purses.

“Look at that. Why would anyone in their right mind want anything in that color? It looks like how I feel with a hangover.”

Does he get hangovers? He did have a cold once, for a couple of hours. He said he picked it up on the street. And that people should be forced to wear tags on their collars saying, DON’T BITE ME, I’M DISEASED. He was fine the next day. If she could shake off a cold that quickly, she wouldn’t complain! He doesn’t drink, or eat anything regular, really. When they go out with her friends, he takes sips at his beer, but she always finishes it for him. He likes it when she drinks; he says it helps him sleep better. He’s learned to sleep at night, sort of. If she’s next to him. If she’s breathing slowly and deeply. Soft and warm.

His hair is long, and always smells a little of fresh snow.

She locks the door because she has a research paper due. She needs her sleep, and she needs her strength, and he’s hard on both of them. He leaves little tributes outside her door, iron-rich things like spinach salad with walnuts in takeaway boxes from the fancy bistro, and half bottles of red wine. Once he even left a steak, nicely cooked, wrapped in tinfoil.

She has no idea where he sleeps when he’s not with her. She really doesn’t want to know. Maybe he doesn’t sleep at all. Maybe sleep is another sensual luxury that he indulges in just for the pleasure with his lovers, like sex.

The truth is, she’s mad at him right now. She’s banging her brains against the library every night, reading through microfiche and digging around in books she needs to wear special gloves to open, trying to find out what happened to a nascent rebellion when the river froze, and wolves came down from the hills – or at least to make a reasonable argument that her theory about sumptuary laws and printing presses is correct.

But her arguments are stupid. Her theories have holes in them. Giant, fact-sized holes. The documentation’s just not there.

And so she spends day after day combing through files, and night after night poring over printed texts and unedited letters of people with bad handwriting and lousy crummy ink that fades after a mere three hundred years or so, most of it insanely boring. Looking for something that might not even be there, for evidence of a fact that may never have existed in the first place.

It’s not that she wants to be famous, or even to prove anything to anyone else, really. That would be nice, but that’s not it. She loves knowing about things that are gone. She wants so badly to know the truth.

And he knows. She knows he knows. He was there.

There’s his hair, for one thing. It’s about the right length for the period she’s researching, and it stays that way, captured, like the rest of his body, at the time of his transformation. Whenever he tries to cut it shorter – and of course, he let her try it once herself – it grows right back, almost overnight.

“I’m a self-regenerating organism,” he says proudly. Proud of his vocabulary, proud of his scientific factoids. Those, he doesn’t have any trouble remembering.

Was he a scholar, before? She can bet he wasn’t a peasant. Not that a peasant couldn’t have been born smart, and educated himself over the years. But not him. She’d bet the farm her lover never bowed low to anyone. He was someone who was always at the center of things. His original name might not ring down through the ages, but he would have known the ones whose did.

And so she’s asked him. Tell me about the wolf hunts. The Thousand Candle Ball. The plague.

“I can’t remember,” he says, no matter what. “It’s too long ago. You can’t expect me to remember that.”

She is beginning to suspect that it’s because it’s true. He really can’t remember anything. He loses his car keys, he forgets to tell her that her mother called. She’s given up on her birthday. It’s coming up, and she knows he hasn’t a clue.

She finds herself scanning the books, not for the facts she needs, but for old engravings that look like him. Here’s a page in a book: soberly dressed men in lace collars all signing a document. The Civil Compact of 1635. Is he the one standing off to the side of the table, as if he’s proofreading their signatures? She’s seen that look on his face, keen and critical and mocking. Can she dig out the names of all the signers? That shouldn’t be hard. There are complete lists of them; another scholar’s already done that work.

She scans the list of the Compact signers. Now what? Does she try out each name on him in turn, like the poor queen with Rumpelstiltskin? Does she murmur in his ear all night, a roll call of dead politicos, until he starts up with a cry of “Present, my lord!”?

She checks the date on the picture. Damn: It’s an engraving of a commemorative painting done fifty years after the actual event. The artist would have been making up what everyone looked like, or working off old portraits, or something.

She peers closer at the engraved face and realizes it’s just a bunch of lines, anyway.

She misses him. First she unlocks her door, and then, as if he knows she did, he meets her outside the library and walks her home.

“Do you want dinner?” he asks. He always buys, probably from some centuries-old bank account that has multiplied like her papa always promised: “Just put a penny in, add to it every year, and when you’re all grown up you’ll be able to buy whatever you want!”

She doesn’t want dinner. She wants him. On the stairs to her room, she’s already tearing his clothes off. He has the nicest clothes. (Oh, that savings account!) He has the nicest body under them. A young man’s body, skin dense and firm. An invincible body, no matter how dissolute his character or degraded his memory.

Is he going to grow old with her? Or, rather, is he going to let her grow old with him? She doubts it. A lot. (“Practice on older men,” her grandmother used to say, “but marry a young one.” Oh, Granny!)

He doesn’t ask how her paper’s coming along.

They’re supposed to be going to her study partner’s birthday party. It’s not that far from her flat, but he’s insisted on going the long way round by the river, where it curves and they’ll have to cross the bridges twice. She knows he doesn’t really want to go at all. He hates parties; he hates her friends. She knows he thinks they’re stupid, even though they’re not. Really not: They were all the smartest kids in their graduating classes. He just doesn’t like listening to them talk about their lives. He doesn’t say so, but it depresses him. Her friends are mostly history and literature. He can barely sit still around them. He wants to be mean to them, to skewer them with his scorn for their youth and inexperience and dreams – but if he does, she’ll dump him. She’s made that clear.

He has to come with her, now, because she’s already been to too many parties without him, and missed too many others because of him. At first it was okay to say her busy older boyfriend was working all the time, but they’ve been together too long; it looks like there’s something funny if he never turns up, and the last thing she wants is people worrying about her. She got him to come along tonight by telling him that Theo will be there. Theo is Anna’s boyfriend, and he’s in physics. He adores talking physics with Theo.

Swallows have begun darting over the river, looking for the bugs that swarm there at twilight. The air is getting blue-gray, but he’s still wearing his heavy, trendy sunglasses. Light really does hurt his eyes. That much is true.

“Flower for the lady?”

It’s one of those beggar kids, trying to sell long-stemmed red roses, each one wrapped in cellophane, tied with a ribbon. The kid probably thinks he’s a tourist, because of the glasses.

To her surprise, he stops. He never stops for anyone. He’s looking at the kid. He never does that, either.

“Hey,” he says.

The kid stares back. “Flower?”

Her arm linked in his, she can feel the twitch of him starting to reach for his wallet, then pulling back and letting go. “No, thanks.”

He pulls her along with him, not looking back.

Was it someone he knew before he met her? Too young. His child by his last lover? But he can’t have kids himself; he says he’s sterile. (Good thing!) Suddenly she remembers when she first came here to university, feeling lonely and raw, then one morning on her way to class spotting Sophie from their soccer club back home ahead of her, on the square, waiting for the light to change. And then realizing it couldn’t be, because Sophie had been hit by a car last year. It was just someone with the same shoulders, the same hair, same height. It would be like that for him all the time, the people he’d known, when he remembered. He’d see them everywhere. But it would never really be them.

“No flower for me?” she says, to recapture his attention. Maybe she’ll even learn something this time. He’s shaken. She knows the signs.

“When I buy you flowers, they won’t look like that.” He loosens his grip on her arm. “Have I ever bought you flowers?”

“Sure,” she says airily. “Don’t you remember that huge basket of lilies and white roses?” He looks at her sideways. He doesn’t quite believe her, but he’s trying to remember, just in case. “And the big bunch of hydrangeas you brought when I got the honors in folklore? I had to borrow a vase from Anna downstairs to hold them all. But my favorite was the rosebuds and freesias you gave me on my birthday.”

He is still walking. But slowly. She feels the tension in his arm. “Did I?”

“No.” She walks past him, now, her heels clicking on the pavement. “Of course not.”

He lets her get a little ahead of him, but only a little. By the time he’s caught up with her, she’s a little sorry. But only a little.

“Hey,” he says. He takes off his sunglasses. Hair falls into his eyes. He pushes it back with one hand. “Not everyone gets honors in folklore.”

“You didn’t even know me then.”

“I didn’t know you liked getting flowers,” he says innocently.

“All women like flowers. You’ve had how many centuries of us, and you can’t even remember that one stupid thing?”

He slings a pebble from the embankment into the water. Then he steps back, to watch it fall. The river is running strong. She can’t see it hit the water, but maybe he can.

“In foreign lands,” he announces, “ancient heroes sleep in caves, waiting for a horn to be blown or a bell to be rung, whereupon they spring into action in their country’s hour of greatest need.” Moodily, he slings another pebble. “Lucky bastards. Nothing to do but dream of ancient glory till it’s time for a remix. Our motherland discourages such sloth.”

“Really?”

“Really. No lying around when the land is in peril. Not here. Oh, no. We’ve got a better system in place.”

Finally! She can’t believe he’s telling her this. “And you’re it?”

“I’m it.”

She keeps her voice level, nonchalant. “I’ve always wondered how anyone could decide when the hour of greatest need was, anyway.”

“Me, too. Every year’s got plenty of hours, believe me.”

“That must be a lot of work.”

“All the work, and none of the glory.” Another pebble. “How do you think we kept our borders intact until ’41? When the Russians were boiling shoe leather?”

She shudders with delight. “You ate Nazis?”

“Ate?” He looks down his nose at her. “What do I look like, an ambulating garbage disposal? I just scared the crap out of them.” His head, lifted against the horizon, is too perfect, like a profile on a coin, a medal of heroism. “Well, certainly I drew a little sustenance first. Waste Not in Wartime and all that.” (She remembers her grandmother telling her that slogan.) “But foreign blood does not nourish like the blood of the land.”

“Is that why you hate to travel?”

“One reason.”

“The blood of the land?”

He draws a little closer to her. And he was close before. He puts one hand on the back of her head and bends down to smell her hair.

Her heart starts slamming like it’s working for him already. She lifts her chin and reaches up to draw his head down to her. Someone passing would think they were just any couple, nuzzling on a picturesque riverbank. They might even wind up in some tactless tourist’s photos. He pulls her tighter, getting her neck right up against his mouth.

“I used to be tall,” he mutters. “I mean really, really tall. People would stare at me on the street. That tall. Now I’m, what, just normal?”

“You’re hardly normal.” She always feels a giddy, reckless joy with his mouth near her veins.

“After the war,” he growls. “All that nutrition. Milk. Marshall Plan. A race of giants. And now it’s vitamins. I’ll end up having to date midgets my own size.”

He might have said more, but she doesn’t hear it because the blood is pounding in her ears. Sweet, it’s so sweet letting him take her into himself. If they were home, she’d take him into her, too. She takes a deep breath of air, the best air she’s ever breathed. She doesn’t want him to stop, but he does.

She’s lost track of time, but the birds are still swirling; it hasn’t been long. She clutches at the wool of his jacket, because otherwise she knows she’s going to fall. He’s so tender with her, now, as he pulls away. He wipes his mouth quickly with a white cotton handkerchief. He’ll never use a paper tissue, and there’s never much to wipe, but he always does it anyway.

He puts an arm around her, letting her lean against him as they walk along the river. He’s buzzing with life energy, as the sun is going down. “Come home,” he says. “Come home with me. Come home.”

He’s always up for it when he’s had a drink. He can’t even function when he hasn’t.

She’s fuzzy, and she lets a possible clue go by, still thinking of what he said before. “You’re a hero,” she says dreamily. “You patrol the borders in time of need.”