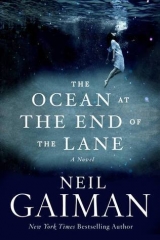

Текст книги "The ocean at the end of the lane"

Автор книги: Neil Gaiman

Жанры:

Современная проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

Nothing. A wet wind that gusted and was gone.

Lettie said, “P’raps they’ve all gone home . . . ?”

“Be nice if they had,” said Ginnie. “All this palaver and nonsense.”

I felt guilty. It was, I knew, my fault. If I had kept hold of Lettie’s hand none of this would have happened. Ursula Monkton, the hunger birds, these things were undoubtedly my responsibility. Even what had happened—or now, had, perhaps, no longer happened—in the cold bath, the previous night.

I had a thought.

“Can’t you just snip it out? The thing in my heart, that they want? Maybe you could snip it out like your granny snipped things last night?”

Lettie squeezed my hand in the dark.

“Maybe Gran could do that if she was here,” she said. “I can’t. I don’t think Mum can either. It’s really hard, snipping things out of time: you have to make sure that the edges all line up, and even Gran doesn’t always get it right. And this would be harder than that. It’s a real thing. I don’t think even Gran could take it out of you without hurting your heart. And you need your heart.” Then she said, “They’re coming.”

But I knew something was happening, knew it before she said anything. For the second time I saw the ground begin to glow golden; I watched the trees and the grass, the hedgerows and the willow clumps and the last stray daffodils begin to shine with a burnished half-light. I looked around, half-fearful, half with wonder, and I observed that the light was brightest behind the house and over to the west, where the pond was.

I heard the beating of mighty wings, and a series of low thumps. I turned and I saw them: the vultures of the void, the carrion kind, the hunger birds.

They were not shadows any longer, not here, not in this place. They were all-too-real, and they landed in the darkness, just beyond the golden glow of the ground. They landed in the air and in trees, and they shuffled forward, as close as they could get to the golden ground of the Hempstocks’ farm. They were huge—each of them was much bigger than I was.

I would have been hard-pressed to describe their faces, though. I could see them, look at them, take in every feature, but the moment I looked away they were gone, and there was nothing in my mind where the hunger birds had been but tearing beaks and talons, or wriggling tentacles, or hairy, chitinous mandibles. I could not keep their true faces in my head. When I turned away the only knowledge I retained was that they had been looking directly at me, and that they were ravenous.

“Right, my proud beauties,” said Ginnie Hempstock, loudly. Her hands were on the hips of her brown coat. “You can’t stay here. You know that. Time to get a move on.” And then she said simply, “Hop it.”

They shifted but they did not move, the innumerable hunger birds, and began to make a noise. I thought that they were whispering amongst themselves, and then it seemed to me that the noise they were making was an amused chuckle.

I heard their voices, distinct but twining together, so I could not tell which creature was speaking.

– We are hunger birds. We have devoured palaces and worlds and kings and stars. We can stay wherever we wish to stay.

– We perform our function.

– We are necessary.

And they laughed so loudly it sounded like a train approaching. I squeezed Lettie’s hand, and she squeezed mine.

– Give us the boy.

Ginnie said, “You’re wasting your time, and you’re wasting mine. Go home.”

– We were summoned here. We do not need to leave until we have done what we came here for. We restore things to the way they are meant to be. Will you deprive us of our function?

“Course I will,” said Ginnie. “You’ve had your dinner. Now you’re just making nuisances of yourselves. Be off with you. Blinking varmints. I wouldn’t give tuppence ha’penny for the lot of you. Go home!” And she shook her hand in a flicking gesture.

One of the creatures let out a long, wailing scream of appetite and frustration.

Lettie’s hold on my hand was firm. She said, “He’s under our protection. He’s on our land. And one step onto our land and that’s the end of you. So go away.”

The creatures seemed to huddle closer. There was silence in the Sussex night: only the rustle of leaves in the wind, only the call of a distant owl, only the sigh of the breeze as it passed; but in that silence I could hear the hunger birds conferring, weighing up their options, plotting their course. And in that silence I felt their eyes upon me.

Something in a tree flapped its huge wings and cried out, a shriek that mingled triumph and delight, an affirmative shout of hunger and joy. I felt something in my heart react to the scream, like the tiniest splinter of ice inside my chest.

– We cannot cross the border. This is true. We cannot take the child from your land. This also is true. We cannot hurt your farm or your creatures . . .

“That’s right. You can’t. So get along with you! Go home. Haven’t you got a war to be getting back to?”

– We cannot hurt your world, true.

– But we can hurt this one.

One of the hunger birds reached a sharp beak down to the ground at its feet, and began to tear at it—not as a creature that eats earth and grass, but as if it were eating a curtain or a piece of scenery with the world painted on it. Where it devoured the grass, nothing remained—a perfect nothing, only a color that reminded me of gray, but a formless, pulsing gray like the shifting static of our television screen when you dislodged the aerial cord and the picture had gone completely.

This was the void. Not blackness, not nothingness. This was what lay beneath the thinly painted scrim of reality.

And the hunger birds began to flap and to flock.

They landed on a huge oak tree and they tore at it and they wolfed it down, and in moments the tree was gone, along with everything that had been behind it.

A fox slipped out of a hedgerow and slunk down the lane, its eyes and mask and brush illuminated golden by the farm-light. Before it had made it halfway across the road it had been ripped from the world, and there was only void behind it.

Lettie said, “What he said before. We have to wake Gran.”

“She won’t like that,” said Ginnie. “Might as well try and wake a—”

“Dunt matter. If we can’t wake her up, they’ll destroy the whole of this creation.”

Ginnie said only, “I don’t know how.”

A clump of hunger birds flew up to a patch of the night sky where stars could be seen through the breaks in the clouds, and they tore at a kite-shaped constellation I could never have named, and they scratched and they rent and they gulped and they swallowed. In a handful of heartbeats, where the constellation and sky had been, there was now only a pulsing nothingness that hurt my eyes if I looked at it directly.

I was a normal child. Which is to say, I was selfish and I was not entirely convinced of the existence of things that were not me, and I was certain, rock-solid unshakably certain, that I was the most important thing in creation. There was nothing that was more important to me than I was.

Even so, I understood what I was seeing. The hunger birds would—no, they were—ripping the world away, tearing it into nothing. Soon enough, there would be no world. My mother, my father, my sister, my house, my school friends, my town, my grandparents, London, the Natural History Museum, France, television, books, ancient Egypt—because of me, all these things would be gone, and there would be nothing in their place.

I did not want to die. More than that, I did not want to die as Ursula Monkton had died, beneath the rending talons and beaks of things that may not even have had legs or faces.

I did not want to die at all. Understand that.

But I could not let everything be destroyed, when I had it in my power to stop the destruction.

I let go of Lettie Hempstock’s hand and I ran, as fast as I could, knowing that to hesitate, even to slow down, would be to change my mind, which would be the worst thing that I could do, which would be to save my life.

How far did I run? Not far, I suppose, as these things go.

Lettie Hempstock was shouting at me to stop, but still, I ran, crossing the farmland, where every blade of grass, every pebble on the lane, every willow tree and hazel hedge glowed golden, and I ran toward the darkness beyond the Hempstock land. I ran and I hated myself for running, as I had hated myself the time I had jumped from the high board at the swimming pool. I knew there was no going back, that there was no way that this could end in anything but pain, and I knew that I was willing to exchange my life for the world.

They took off into the air, the hunger birds, as I ran toward them, as pigeons will rise when you run at them. They wheeled and they circled, deep shadows in the dark.

I stood there in the darkness and I waited for them to descend. I waited for their beaks to tear at my chest, and for them to devour my heart.

I stood there for perhaps two heartbeats, and it felt like forever.

It happened.

Something slammed into me from behind and knocked me down into the mud on the side of the lane, face-first. I saw bursts of light that were not there. The ground hit my stomach, and the wind was knocked out of me.

(A ghost-memory rises, here: a phantom moment, a shaky reflection in the pool of remembrance. I know how it would have felt when the scavengers took my heart. How it felt as the hunger birds, all mouth, tore into my chest and snatched out my heart, still pumping, and devoured it to get at what was hidden inside it. I know how that feels, as if it was truly a part of my life, of my death. And then the memory snips and rips, neatly, and—)

A voice said, “Idiot! Don’t move. Just don’t,” and the voice was Lettie Hempstock’s, and I could not have moved if I had wanted to. She was on top of me, and she was heavier than I was, and she was pushing me down, face-first, into the grass and the wet earth, and I could see nothing.

I felt them, though.

I felt them crash into her. She was holding me down, making herself a barrier between me and the world.

I heard Lettie’s voice wail in pain.

I felt her shudder and twitch.

There were ugly cries of triumph and hunger, and I could hear my own voice whimpering and sobbing, so loud in my ears . . .

A voice said, “This is unacceptable.”

It was a familiar voice, but still, I could not place it, or move to see who was talking.

Lettie was on top of me, still shaking, but as the voice spoke, she stopped moving. The voice continued, “On what authority do you harm my child?”

A pause. Then,

– She was between us and our lawful prey.

“You’re scavengers. Eaters of offal, of rubbish, of garbage. You’re cleaners. Do you think that you can harm my family?”

I knew who was talking. The voice sounded like Lettie’s gran, like Old Mrs. Hempstock. Like her, I knew, and yet so unlike. If Old Mrs. Hempstock had been an empress, she might have talked like that, her voice more stilted and formal and yet more musical than the old-lady voice I knew.

Something wet and warm was soaking my back.

– No . . . No, lady.

That was the first time I heard fear or doubt in the voice of one of the hunger birds.

“There are pacts, and there are laws and there are treaties, and you have violated all of them.”

Silence then, and it was louder than words could have been. They had nothing to say.

I felt Lettie’s body being rolled off mine, and I looked up to see Ginnie Hempstock’s sensible face. She sat on the ground on the edge of the road, and I buried my face in her bosom. She took me in one arm, and her daughter in the other.

From the shadows, a hunger bird spoke, with a voice that was not a voice, and it said only,

– We are sorry for your loss.

“Sorry?” The word was spat, not said.

Ginnie Hempstock swayed from side to side, crooning low and wordlessly to me and to her daughter. Her arms were around me. I lifted my head and I looked back at the person speaking, my vision blurred by tears.

I stared at her.

It was Old Mrs. Hempstock, I suppose. But it wasn’t. It was Lettie’s gran in the same way that . . .

I mean . . .

She shone silver. Her hair was still long, still white, but now she stood as tall and as straight as a teenager. My eyes had become too used to the darkness, and I could not look at her face to see if it was the face I was familiar with: it was too bright. Magnesium-flare bright. Fireworks Night bright. Midday-sun-reflecting-off-a-silver-coin bright.

I looked at her as long as I could bear to look, and then I turned my head, screwing my eyes tightly shut, unable to see anything but a pulsating afterimage.

The voice that was like Old Mrs. Hempstock’s said, “Shall I bind you creatures in the heart of a dark star, to feel your pain in a place where every fragment of a moment lasts a thousand years? Shall I invoke the compacts of Creation, and have you all removed from the list of created things, so there never will have been any hunger birds, and anything that wishes to traipse from world to world can do it with impunity?”

I listened for a reply, but heard nothing. Only a whimper, a mewl of pain or of frustration.

“I’m done with you. I will deal with you in my own time and in my own way. For now I must tend to the children.”

– Yes, lady.

– Thank you, lady.

“Not so fast. Nobody’s going anywhere before you put all those things back like they was. There’s Boötes missing from the sky. There’s an oak tree gone, and a fox. You put them all back, the way they were.” And then the silvery empress voice added, in a voice that was now also unmistakably Old Mrs. Hempstock’s, “Varmints.”

Somebody was humming a tune. I realized, as if from a long way away, that it was me, at the same moment that I remembered what the tune was: “Girls and Boys Come Out to Play.”

. . . the moon doth shine as bright as day.

Leave your supper and leave your meat,

and join your playfellows in the street.

Come with a whoop and come with a call.

Come with a whole heart or not at all . . .

I held on to Ginnie Hempstock. She smelled like a farm and like a kitchen, like animals and like food. She smelled very real, and the realness was what I needed at that moment.

I reached out a hand, tentatively touched Lettie’s shoulder. She did not move or respond.

Ginnie started speaking, then, but at first I did not know if she was talking to herself or to Lettie or to me. “They overstepped their bounds,” she said. “They could have hurt you, child, and it would have meant nothing. They could have hurt this world without anything being said—it’s only a world, after all, and they’re just sand grains in the desert, worlds. But Lettie’s a Hempstock. She’s outside of their dominion, my little one. And they hurted her.”

I looked at Lettie. Her head had flopped down, hiding her face. Her eyes were closed.

“Is she going to be all right?” I asked.

Ginnie didn’t reply, just hugged us both the tighter to her bosom, and rocked, and crooned a wordless song.

The farm and its land no longer glowed golden. I could not feel anything in the shadows watching me, not any longer.

“Don’t you worry,” said an old voice, now familiar once more. “You’re safe as houses. Safer’n most houses I’ve seen. They’ve gone.”

“They’ll come back again,” I said. “They want my heart.”

“They’d not come back to this world again for all the tea in China,” said Old Mrs. Hempstock. “Not that they’ve got any use for tea—or for China—no more than a carrion crow does.”

Why had I thought her dressed in silver? She wore a much-patched gray dressing gown over what had to have been a nightie, but a nightie of a kind that had not been fashionable for several hundred years.

The old woman put a hand on her granddaughter’s pale forehead, lifted it up, then let it go.

Lettie’s mother shook her head. “It’s over,” she said.

I understood it then, at the last, and felt foolish for not understanding it sooner. The girl beside me, on her mother’s lap, at her mother’s breast, had given her life for mine.

“They were meant to hurt me, not her,” I said.

“No reason they should’ve taken either of you,” said the old lady, with a sniff. I felt guilt then, guilt beyond anything I had ever felt before.

“We should get her to hospital,” I said, hopefully. “We can call a doctor. Maybe they can make her better.”

Ginnie shook her head.

“Is she dead?” I asked.

“Dead?” repeated the old woman in the dressing gown. She sounded offended. “Has hif,” she said, grandly aspirating each aitch as if that were the only way to convey the gravity of her words to me. “Has hif han ’Empstock would hever do hanything so . . . common . . .”

“She’s hurt,” said Ginnie Hempstock, cuddling me close. “Hurt as badly as she can be hurt. She’s so close to death as makes no odds if we don’t do something about it, and quickly.” A final hug, then, “Off with you, now.” I clambered reluctantly from her lap, and I stood up.

Ginnie Hempstock got to her feet, her daughter’s body limp in her arms. Lettie lolled and was jogged like a rag doll as her mother got up, and I stared at her, shocked beyond measure.

I said, “It was my fault. I’m sorry. I’m really sorry.”

Old Mrs. Hempstock said, “You meant well,” but Ginnie Hempstock said nothing at all. She walked down the lane toward the farm, and then she turned off behind the milking shed. I thought that Lettie was too big to be carried, but Ginnie carried her as if she weighed no more than a kitten, her head and upper body resting on Ginnie’s shoulder, like a sleeping infant being taken upstairs to bed. Ginnie carried her down that path, and beside the hedge, and back, and back, until we reached the pond.

There were no breezes back there, and the night was perfectly still; our path was lit by moonlight and nothing more; the pond, when we got there, was just a pond. No golden, glimmering light. No magical full moon. It was black and dull, with the moon, the true moon, the quarter moon, reflected in it.

I stopped at the edge of the pond, and Old Mrs. Hempstock stopped beside me.

But Ginnie Hempstock kept walking.

She staggered down into the pond, until she was wading thigh-deep, her coat and skirt floating on the water as she waded, breaking the reflected moon into dozens of tiny moons that scattered and re-formed around her.

At the center of the pond, with the black water above her hips, she stopped. She took Lettie from her shoulder, so the girl’s body was supported at the head and at the knees by Ginnie Hempstock’s practical hands; then slowly, so very slowly, she laid Lettie down in the water.

The girl’s body floated on the surface of the pond.

Ginnie took a step back, and then another, never looking away from her daughter.

I heard a rushing noise, as if of an enormous wind coming toward us.

Lettie’s body shook.

There was no breeze, but now there were whitecaps on the surface of the pond. I saw waves, gentle, lapping waves at first, and then bigger waves that broke and slapped at the edge of the pond. One wave crested and crashed down close to me, splashing my clothes and face. I could taste the water’s wetness on my lips, and it was salt.

I whispered, “I’m sorry, Lettie.”

I should have been able to see the other side of the pond. I had seen it a few moments before. But the crashing waves had taken it away, and I could see nothing beyond Lettie’s floating body but the vastness of the lonely ocean, and the dark.

The waves grew bigger. The water began to glow in the moonlight, as it had glowed when it was in a bucket, glowed a pale, perfect blue. The black shape on the surface of the water was the body of the girl who had saved my life.

Bony fingers rested on my shoulder. “What are you apologizing for, boy? For killing her?”

I nodded, not trusting myself to speak.

“She’s not dead. You didn’t kill her, nor did the hunger birds, although they did their best to get to you through her. She’s been given to her ocean. One day, in its own time, the ocean will give her back.”

I thought of corpses and of skeletons with pearls for eyes. I thought of mermaids with tails that flicked when they moved, like my goldfishes’ tails had flicked before my goldfish had stopped moving, to lie, belly up, like Lettie, on the top of the water. I said, “Will she be the same?”

The old woman guffawed, as if I had said the funniest thing in the universe. “Nothing’s ever the same,” she said. “Be it a second later or a hundred years. It’s always churning and roiling. And people change as much as oceans.”

Ginnie clambered out of the water, and she stood at the water’s edge beside me, her head bowed. The waves crashed and smacked and splashed and retreated. There was a distant rumble that became a louder and louder rumble: something was coming toward us, across the ocean. From miles away, from hundreds and hundreds of miles away it came: a thin white line etched in the glowing blue, and it grew as it approached.

The great wave came, and the world rumbled, and I looked up as it reached us: it was taller than trees, than houses, than mind or eyes could hold, or heart could follow.

Only when it reached Lettie Hempstock’s floating body did the enormous wave crash down. I expected to be soaked, or, worse, to be swept away by the angry ocean water, and I raised my arm to cover my face.

There was no splash of breakers, no deafening crash, and when I lowered my arm I could see nothing but the still black water of a pond in the night, and there was nothing on the surface of the pond but a smattering of lily pads and the thoughtful, incomplete reflection of the moon.

Old Mrs. Hempstock was gone, too. I had thought that she was standing beside me, but only Ginnie stood there, next to me, staring down silently into the dark mirror of the little pond.

“Right,” she said. “I’ll take you home.”

There was a Land Rover parked behind the cowshed. The doors were open and the ignition key was in the lock. I sat on the newspaper-covered passenger seat and watched Ginnie Hempstock turn the key. The engine sputtered a few times before it started.

I had not imagined any of the Hempstocks driving. I said, “I didn’t know you had a car.”

“Lots of things you don’t know,” said Mrs. Hempstock, tartly. Then she glanced at me more gently and said, “You can’t know everything.” She backed the Land Rover up and it bumped its way forward across the ruts and the puddles of the back of the farmyard.

There was something on my mind.

“Old Mrs. Hempstock says that Lettie isn’t really dead,” I said. “But she looked dead. I think she is actually dead. I don’t think it’s true that she’s not dead.”

Ginnie looked like she was going to say something about the nature of truth, but all she said was, “Lettie’s hurt. Very badly hurt. The ocean has taken her. Honestly, I don’t know if it will ever give her back. But we can hope, can’t we?”

“Yes.” I squeezed my hands into fists, and I hoped as hard as I knew how.

We bumped and jolted up the lane at fifteen miles per hour.

I said, “Was she—is she—really your daughter?” I didn’t know, I still don’t know, why I asked her that. Perhaps I just wanted to know more about the girl who had saved my life, who had rescued me more than once. I didn’t know anything about her.

“More or less,” said Ginnie. “The men Hempstocks, my brothers, they went out into the world, and they had babies who’ve had babies. There are Hempstock women out there in your world, and I’ll wager each of them is a wonder in her own way. But only Gran and me and Lettie are the pure thing.”

“She didn’t have a daddy?” I asked.

“No.”

“Did you have a daddy?”

“You’re all questions, aren’t you? No, love. We never went in for that sort of thing. You only need men if you want to breed more men.”

I said, “You don’t have to take me home. I could stay with you. I could wait until Lettie comes back from the ocean. I could work on your farm, and carry stuff, and learn to drive a tractor.”

She said, “No,” but she said it kindly. “You get on with your own life. Lettie gave it to you. You just have to grow up and try and be worth it.”

A flash of resentment. It’s hard enough being alive, trying to survive in the world and find your place in it, to do the things you need to do to get by, without wondering if the thing you just did, whatever it was, was worth someone having . . . if not died, then having given up her life. It wasn’t fair.

“Life’s not fair,” said Ginnie, as if I had spoken aloud.

She turned into our driveway, pulled up outside the front door. I got out and she did too.

“Better make it easier for you to go home,” she said.

Mrs. Hempstock rang the doorbell, although the door was never locked, and industriously scraped the soles of her Wellington boots on the doormat until my mother opened the door. She was dressed for bed, and wearing her quilted pink dressing gown.

“Here he is,” said Ginnie. “Safe and sound, the soldier back from the wars. He had a lovely time at our Lettie’s going-away party, but now it’s time for this young man to get his rest.”

My mother looked blank—almost confused—and then the confusion was replaced by a smile, as if the world had just reconfigured itself into a form that made sense.

“Oh, you didn’t have to bring him back,” said my mother. “One of us would have come and picked him up.” Then she looked down at me. “What do you say to Mrs. Hempstock, darling?”

I said it automatically. “Thank-you-for-having-me.”

My mother said, “Very good, dear.” Then, “Lettie’s going away?”

“To Australia,” said Ginnie. “To be with her father. We’ll miss having this little fellow over to play, but, well, we’ll let you know when Lettie comes back. He can come over and play, then.”

I was getting tired. The party had been fun, although I could not remember much about it. I knew that I would not visit the Hempstock farm again, though. Not unless Lettie was there.

Australia was a long, long way away. I wondered how long it would be until she came back from Australia with her father. Years, I supposed. Australia was on the other side of the world, across the ocean . . .

A small part of my mind remembered an alternate pattern of events and then lost it, as if I had woken from a comfortable sleep and looked around, pulled the bedclothes over me, and returned to my dream.

Mrs. Hempstock got back into her ancient Land Rover, so bespattered with mud (I could now see, in the light above the front door) that there was almost no trace of the original paintwork visible, and she backed it up, down the drive, toward the lane.

My mother seemed unbothered that I had returned home in fancy dress clothes at almost eleven at night. She said, “I have some bad news, dear.”

“What’s that?”

“Ursula’s had to leave. Family matters. Pressing family matters. She’s already left. I know how much you children liked her.”

I knew that I didn’t like her, but I said nothing.

There was now nobody sleeping in my bedroom at the top of the stairs. My mother asked if I would like my room back for a while. I said no, unsure of why I was saying no. I could not remember why I disliked Ursula Monkton so much—indeed, I felt faintly guilty for disliking her so absolutely and so irrationally—but I had no desire to return to that bedroom, despite the little yellow handbasin just my size, and I remained in the shared bedroom until our family moved out of that house half a decade later (we children protesting, the adults I think just relieved that their financial difficulties were over).

The house was demolished after we moved out. I would not go and see it standing empty, and refused to witness the demolition. There was too much of my life bound up in those bricks and tiles, those drainpipes and walls.

Years later, my sister, now an adult herself, confided in me that she believed that our mother had fired Ursula Monkton (whom she remembered, so fondly, as the only nice one in a sequence of grumpy childminders) because our father was having an affair with her. It was possible, I agreed. Our parents were still alive then, and I could have asked them, but I didn’t.

My father did not mention the events of those nights, not then, not later.

I finally made friends with my father when I entered my twenties. We had so little in common when I was a boy, and I am certain I had been a disappointment to him. He did not ask for a child with a book, off in its own world. He wanted a son who did what he had done: swam and boxed and played rugby, and drove cars at speed with abandon and joy, but that was not what he had wound up with.

I did not ever go down the lane all the way to the end. I did not think of the white Mini. When I thought of the opal miner, it was in context of the two rough raw opal-rocks that sat on our mantelpiece, and in my memory he always wore a checked shirt and jeans. His face and arms were tan, not the cherry-red of monoxide poisoning, and he had no bow-tie.

Monster, the ginger tomcat the opal miner had left us, had wandered off to be fed by other families, and although we saw him, from time to time, prowling the ditches and trees at the side of the lane, he would not ever come when we called. I was relieved by this, I think. He had never been our cat. We knew it, and so did he.

A story only matters, I suspect, to the extent that the people in the story change. But I was seven when all of these things happened, and I was the same person at the end of it that I was at the beginning, wasn’t I? So was everyone else. They must have been. People don’t change.

Some things changed, though.

A month or so after the events here, and five years before the ramshackle world I lived in was demolished and replaced by trim, squat, regular houses containing smart young people who worked in the city but lived in my town, who made money by moving money from place to place but who did not build or dig or farm or weave, and nine years before I would kiss smiling Callie Anders . . .

I came home from school. The month was May, or perhaps early June. She was waiting by the back door as if she knew precisely where she was and who she was looking for: a young black cat, a little larger than a kitten now, with a white splodge over one ear, and with eyes of an intense and unusual greenish-blue.

She followed me into the house.