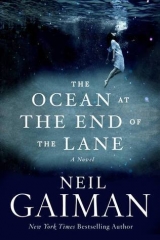

Текст книги "The ocean at the end of the lane"

Автор книги: Neil Gaiman

Жанры:

Современная проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 7 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

“You won’t let her get me, will you?” I asked Lettie.

She shook her head, and together we walked up the winding flinty lane that led to my house and to the thing who called herself Ursula Monkton. I carried the brown-paper bag with my nightwear in it, and Lettie carried her too-big-for-her raffia shopping bag, filled with broken toys, which she had obtained in exchange for a mandrake that screamed and shadows dissolved in vinegar.

Children, as I have said, use back ways and hidden paths, while adults take roads and official paths. We went off the road, took a shortcut that Lettie knew that took us through some fields, then into the extensive abandoned gardens of a rich man’s crumbling house, and then back onto the lane again. We came out just before the place where I had gone over the metal fence.

Lettie sniffed the air. “No varmints yet,” she said. “That’s good.”

“What are varmints?”

She said only, “You’ll know ’em when you see ’em. And I hope you’ll never see ’em.”

“Are we going to sneak in?”

“Why would we do that? We’ll go up the drive and through the front door, like gentry.”

We started up the drive. I said, “Are you going to make a spell and send her away?”

“We don’t do spells,” she said. She sounded a little disappointed to admit it. “We’ll do recipes sometimes. But no spells or cantrips. Gran doesn’t hold with none of that. She says it’s common.”

“So what’s the stuff in the shopping bag for, then?”

“It’s to stop things traveling when you don’t want them to. Mark boundaries.”

In the morning sunlight, my house looked so welcoming and so friendly, with its warm red bricks, and red tile roof. Lettie reached into the shopping bag. She took a marble from it, pushed it into the still-damp soil. Then, instead of going into the house, she turned left, walking the edge of the property. By Mr. Wollery’s vegetable patch we stopped and she took something else from her shopping bag: a headless, legless, pink doll-body, with badly chewed hands. She buried it beside the pea plants.

We picked some pea pods, opened them and ate the peas inside. Peas baffled me. I could not understand why grown-ups would take things that tasted so good when they were freshly-picked and raw, and put them in tin cans, and make them revolting.

Lettie placed a toy giraffe, the small plastic kind you would find in a children’s zoo, or a Noah’s Ark, in the coal shed, beneath a large lump of coal. The coal shed smelled of damp and blackness and of old, crushed forests.

“Will these things make her go away?”

“No.”

“Then what are they for?”

“To stop her going away.”

“But we want her to go away.”

“No. We want her to go home.”

I stared at her: at her short brownish-red hair, her snub-nose, her freckles. She looked three or four years older than me. She might have been three or four thousand years older, or a thousand times older again. I would have trusted her to the gates of Hell and back. But still . . .

“I wish you’d explain properly,” I said. “You talk in mysteries all the time.”

I was not scared, though, and I could not have told you why I was not scared. I trusted Lettie, just as I had trusted her when we had gone in search of the flapping thing beneath the orange sky. I believed in her, and that meant I would come to no harm while I was with her. I knew it in the way I knew that grass was green, that roses had sharp, woody thorns, that breakfast cereal was sweet.

We went into my house through the front door. It was not locked—unless we went away on holidays I do not ever remember it being locked—and we went inside.

My sister was practicing the piano in the front room. We went in. She heard the noise, stopped playing “Chopsticks” and turned around.

She looked at me curiously. “What happened last night?” she asked. “I thought you were in trouble, but then Mummy and Daddy came back and you were just staying with your friends. Why would they say you were sleeping at your friends’? You don’t have any friends.” She noticed Lettie Hempstock, then. “Who’s this?”

“My friend,” I told her. “Where’s the horrible monster?”

“Don’t call her that,” said my sister. “She’s nice. She’s having a lie-down.”

My sister did not say anything about my strange clothes.

Lettie Hempstock took a broken xylophone from her shopping bag and dropped it onto the scree of toys that had accumulated between the piano and the blue toy-box with the detached lid.

“There,” she said. “Now it’s time to go and say hello.”

The first faint stirrings of fear inside my chest, inside my mind. “Go up to her room, you mean?”

“Yup.”

“What’s she doing up there?”

“Doing things to people’s lives,” said Lettie. “Only local people so far. She finds what they think they need and she tries to give it to them. She’s doing it to make the world into something she’ll be happier in. Somewhere more comfortable for her. Somewhere cleaner. And she doesn’t care so much about giving them money, not anymore. Now what she cares about more is people hurting.”

As we went up the stairs Lettie placed something on each step: a clear glass marble with a twist of green inside it; one of the little metal objects we called knucklebones; a bead; a pair of bright blue doll’s eyes, connected at the back with white plastic, to make them open or close; a small red and white horseshoe magnet; a black pebble; a badge, the kind that came attached to birthday cards, with I Am Seven on it; a book of matches; a plastic ladybird with a black magnet in the base; a toy car, half-squashed, its wheels gone; and, last of all, a lead soldier. It was missing a leg.

We were at the top of the stairs. The bedroom door was closed. Lettie said, “She won’t put you in the attic.” Then, without knocking, she opened the door, and she went into the bedroom that had once been mine and, reluctantly, I followed.

Ursula Monkton was lying on the bed with her eyes closed. She was the first adult woman who was not my mother that I had seen naked, and I glanced at her curiously. But the room was more interesting to me than she was.

It was my old bedroom, but it wasn’t. Not anymore. There was the little yellow handbasin, just my size, and the walls were still robin’s-egg blue, as they had been when it was mine. But now strips of cloth hung from the ceiling, gray, ragged cloth strips, like bandages, some only a foot long, others dangling almost all the way to the floor. The window was open and the wind rustled and pushed them, so they swayed, grayly, and it seemed as if perhaps the room was moving, like a tent or a ship at sea.

“You have to go now,” said Lettie.

Ursula Monkton sat up on the bed, and then she opened her eyes, which were now the same gray as the hanging cloths. She said, in a voice that still sounded half-asleep, “I wondered what I would have to do to bring you both here, and look, you came.”

“You didn’t bring us here,” Lettie said. “We came because we wanted to. And I came to give you one last chance to go.”

“I’m not going anywhere,” said Ursula Monkton, and she sounded petulant, like a very small child who wanted something. “I’ve only just got here. I have a house, now. I have pets—his father is just the sweetest thing. I’m making people happy. There is nothing like me anywhere in this whole world. I was looking, just now when you came in. I’m the only one there is. They can’t defend themselves. They don’t know how. So this is the best place in the whole of creation.”

She smiled at us both, brightly. She really was pretty, for a grown-up, but when you are seven, beauty is an abstraction, not an imperative. I wonder what I would have done if she had smiled at me like that now: whether I would have handed my mind or my heart or my identity to her for the asking, as my father did.

“You think this world’s like that,” said Lettie. “You think it’s easy. But it en’t.”

“Of course it is. What are you saying? That you and your family will defend this world against me? You’re the only one who ever leaves the borders of your farm—and you tried to bind me without knowing my name. Your mother wouldn’t have been that foolish. I’m not scared of you, little girl.”

Lettie reached deep into the shopping bag. She pulled out the jam jar with the translucent wormhole inside, and held it out.

“Here’s your way back,” she said. “I’m being kind, and I’m being nice. Trust me. Take it. I don’t think you can get any further to home than the place we met you, with the orange sky, but that’s far enough. I can’t get you from there to where you came from in the first place—I asked Gran, and she says it isn’t even there anymore—but once you’re back we can find a place for you, somewhere similar. Somewhere you’ll be happy. Somewhere you’ll be safe.”

Ursula Monkton got off the bed. She stood up and looked down at us. There were no lightnings wreathing her, not any longer, but she was scarier standing naked in that bedroom than she had been floating in the storm. She was an adult—no, more than an adult. She was old. And I have never felt more like a child.

“I’m so happy here,” she said. “So very, very happy here.” And then she said, almost regretfully, “You’re not.”

I heard a sound, a soft, raggedy, flapping sound. The gray cloths began to detach themselves from the ceiling, one by one. They fell, but not in a straight line. They fell toward us, from all over the room, as if we were magnets, pulling them toward our bodies. The first strip of gray cloth landed on the back of my left hand, and it stuck there. I reached out my right hand and grabbed it, and I pulled the cloth off: it adhered, for a moment, and as it pulled off it made a sucking sound. There was a discolored patch on the back of my left hand, where the cloth had been, and it was as red as if I had been sucking on it for a long, long time, longer and harder than I ever had in real life, and it was beaded with blood. There were pinpricks of red wetness that smeared as I touched it, and then a long bandage-cloth began to attach itself to my legs, and I moved away as a cloth landed on my face and my forehead, and another wrapped itself over my eyes, blinding me, so I pulled at the cloth on my eyes, but now another cloth circled my wrists, bound them together, and my arms were wrapped and bound to my body, and I stumbled, and fell to the floor.

If I pulled against the cloths, they hurt me.

My world was gray. I gave up, then. I lay there, and did not move, concentrated only on breathing through the space the cloth strips had left for my nose. They held me, and they felt alive.

I lay on the carpet, and I listened. There was nothing else I could do.

Ursula said, “I need the boy safe. I promised I’d keep him in the attic, so the attic it shall be. But you, little farm-girl. What shall I do with you? Something appropriate. Perhaps I ought to turn you inside out, so your heart and brains and flesh are all naked and exposed on the outside, and the skin-side’s inside. Then I’ll keep you wrapped up in my room here, with your eyes staring forever at the darkness inside yourself. I can do that.”

“No,” said Lettie. She sounded sad, I thought. “Actually, you can’t. And I gave you your chance.”

“You threatened me. Empty threats.”

“I dunt make threats,” said Lettie. “I really wanted you to have a chance.” And then she said, “When you looked around the world for things like you, didn’t you wonder why there weren’t lots of other old things around? No, you never wondered. You were so happy it was just you here, you never stopped to think.

“Gran always calls your sort of thing fleas, Skarthach of the Keep. I mean, she could call you anything. I think she thinks fleas is funny . . . She doesn’t mind your kind. She says you’re harmless enough. Just a bit stupid. That’s cos there are things that eat fleas, in this part of creation. Varmints, Gran calls them. She dunt like them at all. She says they’re mean, and they’re hard to get rid of. And they’re always hungry.”

“I’m not scared,” said Ursula Monkton. She sounded scared. And then she said, “How did you know my name?”

“Went looking for it this morning. Went looking for other things too. Some boundary markers, to keep you from running too far, getting into more trouble. And a trail of breadcrumbs that leads straight here, to this room. Now, open the jam jar, take out the doorway, and let’s send you home.”

I waited for Ursula Monkton to respond, but she said nothing. There was no answer. Only the slamming of a door, and the sound of footsteps, fast and pounding, running down the stairs.

Lettie’s voice was close to me, and it said, “She would have been better off staying here, and taking me up on my offer.”

I felt her hands tugging at the cloths on my face. They came free with a wet, sucking sound, but they no longer felt alive, and when they came off they fell to the ground and lay there, unmoving. This time there was no blood beaded on my skin. The worst thing that had happened was that my arms and legs had gone to sleep.

Lettie helped me to my feet. She did not look happy.

“Where did she go?” I asked.

“She’s followed the trail out of the house. And she’s scared. Poor thing. She’s so scared.”

“You’re scared too.”

“A bit, yes. Right about now she’s going to find that she’s trapped inside the bounds I put down, I expect,” said Lettie.

We went out of the bedroom. Where the toy soldier at the top of the stairs had been, there was now a rip. That’s the best I can describe it: it was as if someone had taken a photograph of the stairs and then torn out the soldier from the photograph. There was nothing in the space where the soldier had been but a dim grayness that hurt my eyes if I looked at it too long.

“What’s she scared of?”

“You heard. Varmints.”

“Are you scared of varmints, Lettie?”

She hesitated, just a moment too long. Then she said simply, “Yes.”

“But you aren’t scared of her. Of Ursula.”

“I can’t be scared of her. It’s just like Gran says. She’s like a flea, all puffed up with pride and power and lust, like a flea bloated with blood. But she couldn’t have hurt me. I’ve seen off dozens like her, in my time. One as come through in Cromwell’s day—now there was something to talk about. He made folk lonely, that one. They’d hurt themselves just to make the loneliness stop—gouge out their eyes or jump down wells, and all the while that great lummocking thing sits in the cellar of the Duke’s Head, looking like a squat toad big as a bulldog.” We were at the bottom of the stairs, walking down the hall.

“How do you know where she went?”

“Oh, she couldn’t have gone anywhere but the way I laid out for her.” In the front room my sister was still playing “Chopsticks” on the piano.

Da da DUM da da

da da DUM da da

da da DUM da DUM da DUM da da . . .

We walked out of the front door. “He was nasty, that one, back in Cromwell’s day. But we got him out of there just before the hunger birds came.”

“Hunger birds?”

“What Gran calls varmints. The cleaners.”

They didn’t sound bad. I knew that Ursula had been scared of them, but I wasn’t. Why would you be scared of cleaners?

We caught up with Ursula Monkton on the lawn, by the rosebushes. She was holding the jam jar with the drifting wormhole inside it. She looked strange. She tugged at the lid, and then stopped and looked up at the sky. Then she looked back to the jam jar once more.

She ran over to my beech tree, the one with the rope ladder, and she threw the jam jar as hard as she could against the trunk. If she was trying to break it, she failed. The jar simply bounced off, and landed on the moss that half-covered the tangle of roots, and lay there, undamaged.

Ursula Monkton glared at Lettie. “Why?” she said.

“You know why,” said Lettie.

“Why would you let them in?” She had started to cry, and I felt uncomfortable. I did not know what to do when adults cried. It was something I had only seen twice before in my life: I had seen my grandparents cry, when my aunt had died, in hospital, and I had seen my mother cry. Adults should not weep, I knew. They did not have mothers who would comfort them.

I wondered if Ursula Monkton had ever had a mother. She had mud on her face and on her knees, and she was wailing.

I heard a sound in the distance, odd and outlandish: a low thrumming, as if someone had plucked at a taut piece of string.

“It won’t be me that lets them in,” said Lettie Hempstock. “They go where they wants to. They usually don’t come here because there’s nothing for them to eat. Now, there is.”

“Send me back,” said Ursula Monkton. And now I did not think she looked even faintly human. Her face was wrong, somehow: an accidental assemblage of features that simply put me in mind of a human face, like the knobbly gray whorls and lumps on the side of my beech tree, or the patterns in the wooden headboard of the bed at my grandmother’s house, which, if I looked at them wrongly in the moonlight, showed me an old man with his mouth open wide, as if he were screaming.

Lettie picked up the jam jar from the green moss, and twisted the lid. “You’ve gone and got it stuck tight,” she said. She walked over to the rock path, turned the jam jar upside down, holding it at the bottom, and banged it, lid-side-down, once, confidently, against the ground. Then she turned it the right side up, and twisted. This time the lid came off in her hand.

She passed the jam jar to Ursula Monkton, who reached inside it, and pulled out the translucent thing that had once been a hole in my foot. It writhed and wiggled and flexed seemingly in delight at her touch.

She threw it down. It fell onto the grass, and it grew. Only it didn’t grow. It changed: as if it was closer to me than I had thought. I could see through it, from one end to the other. I could have run down it, if the far end of that tunnel had not ended in a bitter orange sky.

As I stared at it, my chest twinged again: an ice-cold feeling, as if I had just eaten so much ice cream that I had chilled my insides.

Ursula Monkton walked toward the tunnel mouth. (How could the tiny wormhole be a tunnel? I could not understand it. It was still a glistening translucent silver-black wormhole, on the grass, no more than a foot or so long. It was as if I had zoomed in on something small, I suppose. But it was also a tunnel, and you could have taken a house through it.)

Then she stopped, and she wailed.

She said, “The way back.” Only that. “Incomplete,” she said. “It’s broken. The last of the gate isn’t there . . .” And she looked around her, troubled and puzzled. She focused on me—not my face, but my chest. And she smiled.

Then she shook. One moment she was an adult woman, naked and muddy, the next, as if she was a flesh-colored umbrella, she unfurled.

And as she unfurled, she reached out, and she grabbed me, pulled me up and high off the ground, and I reached out in fear and held her in my turn.

I was holding flesh. I was fifteen feet or more above the ground, as high as a tree.

I was not holding flesh.

I was holding old fabric, a perished, rotting canvas, and, beneath it, I could feel wood. Not good, solid wood, but the kind of old decayed wood I’d find where trees had crumbled, the kind that always felt wet, that I could pull apart with my fingers, soft wood with tiny beetles in it and woodlice, all filled with threadlike fungus.

It creaked and swayed as it held me.

YOU HAVE BLOCKED THE WAYS, it said to Lettie Hempstock.

“I never blocked nothing,” Lettie said. “You’ve got my friend. Put him down.” She was a long way beneath me, and I was scared of heights and I was scared of the creature that was holding me.

THE PATH IS INCOMPLETE. THE WAYS ARE BLOCKED.

“Put him down. Now. Safely.”

HE COMPLETES THE PATH. THE PATH IS INSIDE HIM.

I was certain that I would die, then.

I did not want to die. My parents had told me that I would not really die, not the real me: that nobody really died, when they died; that my kitten and the opal miner had just taken new bodies and would be back again, soon enough. I did not know if this was true or not. I knew only that I was used to being me, and I liked my books and my grandparents and Lettie Hempstock, and that death would take all these things from me.

I WILL OPEN HIM. THE WAY IS BROKEN. IT REMAINS INSIDE HIM.

I would have kicked, but there was nothing to kick against. I pulled with my fingers at the limb holding me, but my fingernails dug into rotting cloth and soft wood, and beneath it, something as hard as bone; and the creature held me close.

“Let me go!” I shouted. “Let! Me! Go!”

NO.

“Mummy!” I shouted. “Daddy!” Then, “Lettie, make her put me down.”

My parents were not there. Lettie was. She said, “Skarthach. Put him down. I gave you a choice, before. Sending you home will be harder, with the end of your tunnel inside him. But we can do it—and Gran can do it if Mum and me can’t. So put him down.”

IT IS INSIDE HIM. IT IS NOT A TUNNEL. NOT ANY LONGER. IT DOES NOT END. I FASTENED THE PATH INSIDE HIM TOO WELL WHEN I MADE IT AND THE LAST OF IT IS STILL INSIDE HIM. NO MATTER. ALL I NEED TO DO TO GET AWAY FROM HERE IS TO REACH INTO HIS CHEST AND PULL OUT HIS BEATING HEART AND FINISH THE PATH AND OPEN THE DOOR.

It was talking without words, the faceless flapping thing, talking directly inside my head, and yet there was something in its words that reminded me of Ursula Monkton’s pretty, musical voice. I knew it meant what it said.

“All of your chances are used up,” said Lettie, as if she were telling us that the sky was blue. And she raised two fingers to her lips and, shrill and sweet and piercing sharp, she whistled.

They came as if they had been waiting for her call.

High in the sky they were, and black, jet-black, so black it seemed as if they were specks on my eyes, not real things at all. They had wings, but they were not birds. They were older than birds, and they flew in circles and in loops and whorls, dozens of them, hundreds perhaps, and each flapping unbird slowly, ever so slowly, descended.

I found myself imagining a valley filled with dinosaurs, millions of years ago, who had died in battle, or of disease: imagining first the carcasses of the rotting thunder-lizards, bigger than buses, and then the vultures of that aeon: gray-black, naked, winged but featherless; faces from nightmares—beak-like snouts filled with needle-sharp teeth, made for rending and tearing and devouring, and hungry red eyes. These creatures would have descended on the corpses of the great thunder-lizards and left nothing but bones.

Huge, they were, and sleek, and ancient, and it hurt my eyes to look at them.

“Now,” said Lettie Hempstock to Ursula Monkton. “Put him down.”

The thing that held me made no move to drop me. It said nothing, just moved swiftly, like a raggedy tall ship, across the grass toward the tunnel.

I could see the anger in Lettie Hempstock’s face, her fists clenched so tightly the knuckles were white. I could see above us the hunger birds circling, circling . . .

And then one of them dropped from the sky, dropped faster than the mind could imagine. I felt a rush of air beside me, saw a black, black jaw filled with needles and eyes that burned like gas jets, and I heard a ripping noise, like a curtain being torn apart.

The flying thing swooped back up into the sky with a length of gray cloth between its jaws.

I heard a voice wailing inside my head and out of it, and the voice was Ursula Monkton’s.

They descended, then, as if they had all been waiting for the first of their number to move. They fell from the sky onto the thing that held me, nightmares tearing at a nightmare, pulling off strips of fabric, and through it all I heard Ursula Monkton crying.

I ONLY GAVE THEM WHAT THEY NEEDED, she was saying, petulant and afraid. I MADE THEM HAPPY.

“You made my daddy hurt me,” I said, as the thing that was holding me flailed at the nightmares that tore at its fabric. The hunger birds ripped at it, each bird silently tearing away strips of cloth and flapping heavily back into the sky, to wheel and descend again.

I NEVER MADE ANY OF THEM DO ANYTHING, it told me. For a moment I thought it was laughing at me, then the laughter became a scream, so loud it hurt my ears and my mind.

It was as if the wind left the tattered sails then, and the thing that was holding me crumpled slowly to the ground.

I hit the grass hard, skinning my knees and the palms of my hands. Lettie pulled me up, helped me away from the fallen, crumpled remains of what had once called itself Ursula Monkton.

There was still gray cloth, but it was not cloth: it writhed and rolled on the ground around me, blown by no wind that I could perceive, a squirming maggoty mess.

The hunger birds landed on it like seagulls on a beach of stranded fish, and they tore at it as if they had not eaten for a thousand years and needed to stuff themselves now, as it might be another thousand years or longer before they would eat again. They tore at the gray stuff and in my mind I could hear it screaming the whole time as they crammed its rotting-canvas flesh into their sharp maws.

Lettie held my arm. She didn’t say anything.

We waited.

And when the screaming stopped, I knew that Ursula Monkton was gone forever.

Once the black creatures had finished devouring the thing on the grass, and nothing remained, not even the tiniest scrap of gray cloth, then they turned their attentions to the translucent tunnel, which wiggled and wriggled and twitched like a living thing. Several of them grasped it in their claws, and they flew up with it, pulling it into the sky while the rest of them tore at it, demolishing it with their hungry mouths.

I thought that when they finished it they would go away, return to wherever they had come from, but they did not. They descended. I tried to count them, as they landed, and I failed. I had thought that there were hundreds of them, but I might have been wrong. There might have been twenty of them. There might have been a thousand. I could not explain it: perhaps they were from a place where such things as counting didn’t apply, somewhere outside of time and numbers.

They landed, and I stared at them, but saw nothing but shadows.

So many shadows.

And they were staring at us.

Lettie said, “You’ve done what you came here for. You got your prey. You cleaned up. You can go home now.”

The shadows did not move.

She said, “Go!”

The shadows on the grass stayed exactly where they were. If anything they seemed darker, more real than they had been before.

– You have no power over us.

“Perhaps I don’t,” said Lettie. “But I called you here, and now I’m telling you to go home. You devoured Skarthach of the Keep. You’ve done your business. Now clear off.”

– We are cleaners. We came to clean.

“Yes, and you’ve cleaned the thing you came for. Go home.”

– Not everything, sighed the wind in the rhododendron bushes and the rustle of the grass.

Lettie turned to me, and put her arms around me. “Come on,” she said. “Quickly.”

We walked across the lawn, rapidly. “I’m taking you down to the fairy ring,” she said. “You have to wait there until I come and get you. Don’t leave. Not for anything.”

“Why not?”

“Because something bad could happen to you. I don’t think I could get you back to the farmhouse safely, and I can’t fix this on my own. But you’re safe in the ring. Whatever you see, whatever you hear, don’t leave it. Just stay where you are and you’ll be fine.”

“It’s not a real fairy ring,” I told her. “That’s just our games. It’s a green circle of grass.”

“It is what it is,” she said. “Nothing that wants to hurt you can cross it. Now, stay inside.” She squeezed my hand, and walked me into the green grass circle. Then she ran off, into the rhododendron bushes, and she was gone.

The shadows began to gather around the edges of the circle. Formless blotches that were only there, really there, when glimpsed from the corners of my eyes. That was when they looked birdlike. That was when they looked hungry.

I have never been as frightened as I was in that grass circle with the dead tree in the center, on that afternoon. No birds sang, no insects hummed or buzzed. Nothing changed. I heard the rustle of the leaves and the sigh of the grass as the wind passed over it, but Lettie Hempstock was not there, and I heard no voices in the breeze. There was nothing to scare me but shadows, and the shadows were not even properly visible when I looked at them directly.

The sun got lower in the sky, and the shadows blurred into the dusk, became, if anything, more indistinct, so now I was not certain that anything was there at all. But I did not leave the grass circle.

“Hey! Boy!”

I turned. He walked across the lawn toward me. He was dressed as he had been the last time I had seen him: a dinner jacket, a frilly white shirt, a black bow-tie. His face was still an alarming cherry-red, as if he had just spent too long on the beach, but his hands were white. He looked like a waxwork, not a person, something you would expect to see in the Chamber of Horrors. He grinned when he saw me looking at him, and now he looked like a waxwork that was smiling, and I swallowed, and wished that the sun was out again.

“Come on, boy,” said the opal miner. “You’re just prolonging the inevitable.”

I did not say a word. I watched him. His shiny black shoes walked up to the grass circle, but they did not cross it.

My heart was pounding so hard in my chest I was certain that he must have heard it. My neck and scalp prickled.

“Boy,” he said, in his sharp South African accent. “They need to finish this up. It’s what they do: they’re the carrion kind, the vultures of the void. Their job. Clean up the last remnants of the mess. Nice and neat. Pull you from the world and it will be as if you never existed. Just go with it. It won’t hurt.”

I stared at him. Adults only ever said that when it, whatever it happened to be, was going to hurt so much.

The dead man in the dinner jacket turned his head slowly, until his face was looking at mine. His eyes were rolled back in his head, and seemed to be staring blindly at the sky above us, like a sleepwalker.

“She can’t save you, your little friend,” he said. “Your fate was sealed and decided days ago, when their prey used you as a door from its place to this one, and she fastened her path in your heart.”