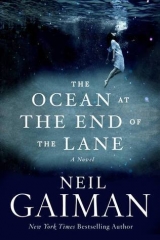

Текст книги "The ocean at the end of the lane"

Автор книги: Neil Gaiman

Жанры:

Современная проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 2 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

A stocky woman came in. Her red-brown hair was streaked with gray, and cut short. She had apple cheeks, a dark green skirt that went to her knees, and Wellington boots. She said, “This must be the boy from the top of the lane. Such a business going on with that car. There’ll be five of them needing tea soon.”

Lettie filled a huge copper kettle from the tap. She lit a gas hob with a match and put the kettle onto the flame. Then she took down five chipped mugs from a cupboard, and hesitated, looking at the woman. The woman said, “You’re right. Six. The doctor will be here too.”

Then the woman pursed her lips and made a tchutch! noise. “They’ve missed the note,” she said. “He wrote it so carefully too, folded it and put it in his breast pocket, and they haven’t looked there yet.”

“What does it say?” asked Lettie.

“Read it yourself,” said the woman. I thought she was Lettie’s mother. She seemed like she was somebody’s mother. Then she said, “It says that he took all the money that his friends had given him to smuggle out of South Africa and bank for them in England, along with all the money he’d made over the years mining for opals, and he went to the casino in Brighton, to gamble, but he only meant to gamble with his own money. And then he only meant to dip into the money his friends had given him until he had made back the money he had lost.

“And then he didn’t have anything,” said the woman, “and all was dark.”

“That’s not what he wrote, though,” said Lettie, squinting her eyes. “What he wrote was,

“To all my friends,

“Am so sorry it was not like I meant to and hope you can find it in your hearts to forgive me for I cannot forgive myself.”

“Same thing,” said the older woman. She turned to me. “I’m Lettie’s ma,” she said. “You’ll have met my mother already, in the milking shed. I’m Mrs. Hempstock, but she was Mrs. Hempstock before me, so she’s Old Mrs. Hempstock. This is Hempstock Farm. It’s the oldest farm hereabouts. It’s in the Domesday Book.”

I wondered why they were all called Hempstock, those women, but I did not ask, any more than I dared to ask how they knew about the suicide note or what the opal miner had thought as he died. They were perfectly matter-of-fact about it.

Lettie said, “I nudged him to look in the breast pocket. He’ll think he thought of it himself.”

“There’s a good girl,” said Mrs. Hempstock. “They’ll be in here when the kettle boils to ask if I’ve seen anything unusual and to have their tea. Why don’t you take the boy down to the pond?”

“It’s not a pond,” said Lettie. “It’s my ocean.” She turned to me and said, “Come on.” She led me out of the house the way we had come.

The day was still gray.

We walked around the house, down the cow path.

“Is it a real ocean?” I asked.

“Oh yes,” she said.

We came on it suddenly: a wooden shed, an old bench, and between them, a duck pond, dark water spotted with duckweed and lily pads. There was a dead fish, silver as a coin, floating on its side on the surface.

“That’s not good,” said Lettie.

“I thought you said it was an ocean,” I told her. “It’s just a pond, really.”

“It is an ocean,” she said. “We came across it when I was just a baby, from the old country.”

Lettie went into the shed and came out with a long bamboo pole, with what looked like a shrimping net on the end. She leaned over, carefully pushed the net beneath the dead fish. She pulled it out.

“But Hempstock Farm is in the Domesday Book,” I said. “Your mum said so. And that was William the Conqueror.”

“Yes,” said Lettie Hempstock.

She took the dead fish out of the net and examined it. It was still soft, not stiff, and it flopped in her hand. I had never seen so many colors: it was silver, yes, but beneath the silver was blue and green and purple and each scale was tipped with black.

“What kind of fish is it?” I asked.

“This is very odd,” she said. “I mean, mostly fish in this ocean don’t die anyway.” She produced a horn-handled pocketknife, although I could not have told you from where, and she pushed it into the stomach of the fish, and sliced along, toward the tail.

“This is what killed her,” said Lettie.

She took something from inside the fish. Then she put it, still greasy from the fish-guts, into my hand. I bent down, dipped it into the water, rubbed my fingers across it to clean it off. I stared at it. Queen Victoria’s face stared back at me.

“Sixpence?” I said. “The fish ate a sixpence?”

“It’s not good, is it?” said Lettie Hempstock. There was a little sunshine now: it showed the freckles that clustered across her cheeks and nose, and, where the sunlight touched her hair, it was a coppery red. And then she said, “Your father’s wondering where you are. Time to be getting back.”

I tried to give her the little silver sixpence, but she shook her head. “You keep it,” she said. “You can buy chocolates, or sherbet lemons.”

“I don’t think I can,” I said. “It’s too small. I don’t know if shops will take sixpences like these nowadays.”

“Then put it in your piggy bank,” she said. “It might bring you luck.” She said this doubtfully, as if she were uncertain what kind of luck it would bring.

The policemen and my father and two men in brown suits and ties were standing in the farmhouse kitchen. One of the men told me he was a policeman, but he wasn’t wearing a uniform, which I thought was disappointing: if I were a policeman, I was certain, I would wear my uniform whenever I could. The other man with a suit and tie I recognized as Doctor Smithson, our family doctor. They were finishing their tea.

My father thanked Mrs. Hempstock and Lettie for taking care of me, and they said I was no trouble at all, and that I could come again. The policeman who had driven us down to the Mini now drove us back to our house, and dropped us off at the end of the drive.

“Probably best if you don’t talk about this to your sister,” said my father.

I didn’t want to talk about it to anybody. I had found a special place, and made a new friend, and lost my comic, and I was holding an old-fashioned silver sixpence tightly in my hand.

I said, “What makes the ocean different to the sea?”

“Bigger,” said my father. “An ocean is much bigger than the sea. Why?”

“Just thinking,” I said. “Could you have an ocean that was as small as a pond?”

“No,” said my father. “Ponds are pond-sized, lakes are lake-sized. Seas are seas and oceans are oceans. Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic. I think that’s all of the oceans there are.”

My father went up to his bedroom, to talk to my mum and to be on the phone up there. I dropped the silver sixpence into my piggy bank. It was the kind of china piggy bank from which nothing could be removed. One day, when it could hold no more coins, I would be allowed to break it, but it was far from full.

I never saw the white Mini again. Two days later, on Monday, my father took delivery of a black Rover, with cracked red leather seats. It was a bigger car than the Mini had been, but not as comfortable. The smell of old cigars permeated the leather upholstery, and long drives in the back of the Rover always left us feeling car-sick.

The black Rover was not the only thing to arrive on Monday morning. I also received a letter.

I was seven years old, and I never got letters. I got cards, on my birthday, from my grandparents, and from Ellen Henderson, my mother’s friend whom I did not know. On my birthday Ellen Henderson, who lived in a camper van, would send me a handkerchief. I did not get letters. Even so, I would check the post every day to see if there was anything for me.

And, that morning, there was.

I opened it, did not understand what I was looking at, and took it to my mother.

“You’ve won the Premium Bonds,” she said.

“What does that mean?”

“When you were born—when all of her grandchildren were born—your grandma bought you a Premium Bond. And when the number gets chosen you can win thousands of pounds.”

“Did I win thousands of pounds?”

“No.” She looked at the slip of paper. “You’ve won twenty-five pounds.”

I was sad not to have won thousands of pounds (I already knew what I would buy with it. I would buy a place to go and be alone, like a Batcave, with a hidden entrance), but I was delighted to be in possession of a fortune beyond my previous imaginings. Twenty-five pounds. I could buy four little blackjack or fruit salad sweets for a penny: they were a farthing each, although there were no more farthings. Twenty-five pounds, at 240 pennies to the pound and four sweets to the penny, was . . . more sweets than I could easily imagine.

“I’ll put it in your post office account,” said my mother, crushing my dreams.

I did not have any more sweets than I had had that morning. Even so, I was rich. Twenty-five pounds richer than I had been moments before. I had never won anything, ever.

I made her show me the piece of paper with my name on it again, before she put it into her handbag.

That was Monday morning. In the afternoon the ancient Mr. Wollery, who came in on Monday and Thursday afternoons to do some gardening (Mrs. Wollery, his equally ancient wife, who wore galoshes, huge semi-transparent overshoes, would come in on Wednesday afternoons and clean), was digging in the vegetable garden and dug up a bottle filled with pennies and halfpennies and threepenny bits and even farthings. None of the coins was dated later than 1937, and I spent the afternoon polishing them with brown sauce and vinegar, to make them shine.

My mother put the bottle of old coins on the mantelpiece of the dining room, and said that she expected that a coin collector might pay several pounds for them.

I went to bed that night happy and excited. I was rich. Buried treasure had been discovered. The world was a good place.

I don’t remember how the dreams started. But that’s the way of dreams, isn’t it? I know that I was in school, and having a bad day, hiding from the kinds of kids who hit me and called me names, but they found me anyway, deep in the rhododendron thicket behind the school, and I knew it must be a dream (but in the dream I didn’t know this, it was real and it was true) because my grandfather was with them, and his friends, old men with gray skin and hacking coughs. They held sharp pencils, the kind that drew blood when you were jabbed with them. I ran from them, but they were faster than I was, the old men and the big boys, and, in the boys’ toilets, where I had hidden in a cubicle, they caught up with me. They held me down, forced my mouth wide open.

My grandfather (but it was not my grandfather: it was really a waxwork of my grandfather, intent on selling me to anatomy) held something sharp and glittering, and he began pushing it into my mouth with his stubby fingers. It was hard and sharp and familiar, and it made me gag and choke. My mouth filled with a metallic taste.

They were looking at me with mean, triumphant eyes, all the people in the boys’ toilets, and I tried not to choke on the thing in my throat, determined not to give them that satisfaction.

I woke and I was choking.

I could not breathe. There was something in my throat, hard and sharp and stopping me from breathing or from crying out. I began to cough as I woke, tears streaming down my cheeks, nose running.

I pushed my fingers as deeply as I could into my mouth, desperate and panicked and determined. With the tip of my forefinger I felt the edge of something hard. I put the middle finger on the other side of it, choking myself, clamping the thing between them, and I pulled whatever it was out of my throat.

I gasped for breath, and then I half-vomited onto my bedsheets, threw up a clear drool flecked with blood, from where the thing had cut my throat as I had pulled it out.

I did not look at the thing. It was tight in my hand, slimy with my saliva and my phlegm. I did not want to look at it. I did not want it to exist, the bridge between my dream and the waking world.

I ran down the hallway to the bathroom, down at the far end of the house. I washed my mouth out, drank directly from the cold tap, spat red into the white sink. Only when I’d done that did I sit on the side of the white bathtub and open my hand. I was scared.

But what was in my hand—what had been in my throat—wasn’t scary. It was only a coin: a silver shilling.

I went back to the bedroom. I dressed myself, cleaned the vomit from my sheets as best I could with a damp face-flannel. I hoped that the sheets would dry before I had to sleep in the bed that night. Then I went downstairs.

I wanted to tell someone about the shilling, but I did not know who to tell. I knew enough about adults to know that if I did tell them what had happened, I would not be believed. Adults rarely seemed to believe me when I told the truth anyway. Why would they believe me about something so unlikely?

My sister was playing in the back garden with some of her friends. She ran over to me angrily when she saw me. She said, “I hate you. I’m telling Mummy and Daddy when they come home.”

“What?”

“You know,” she said. “I know it was you.”

“What was me?”

“Throwing coins at me. At all of us. From the bushes. That was just nasty.”

“But I didn’t.”

“It hurt.”

She went back to her friends, and they all glared at me. My throat felt painful and ragged.

I walked down the drive. I don’t know where I was thinking of going—I just didn’t want to be there any longer.

Lettie Hempstock was standing at the bottom of the drive, beneath the chestnut trees. She looked as if she had been waiting for a hundred years and could wait for another hundred. She wore a white dress, but the light coming through the chestnut’s young spring leaves stained it green.

I said, “Hello.”

She said, “You were having bad dreams, weren’t you?”

I took the shilling out of my pocket and showed it to her. “I was choking on it,” I told her. “When I woke up. But I don’t know how it got into my mouth. If someone had put it into my mouth, I would have woken up. It was just in there, when I woke.”

“Yes,” she said.

“My sister says I threw coins at them from the bushes, but I didn’t.”

“No,” she agreed. “You didn’t.”

I said, “Lettie? What’s happening?”

“Oh,” she said, as if it was obvious. “Someone’s just trying to give people money, that’s all. But it’s doing it very badly, and it’s stirring things up around here that should be asleep. And that’s not good.”

“Is it something to do with the man who died?”

“Something to do with him. Yes.”

“Is he doing this?”

She shook her head. Then she said, “Have you had breakfast?”

I shook my head.

“Well then,” she said. “Come on.”

We walked down the lane together. There were a few houses down the lane, here and there, back then, and she pointed to them as we went past. “In that house,” said Lettie Hempstock, “a man dreamed of being sold and of being turned into money. Now he’s started seeing things in mirrors.”

“What kinds of things?”

“Himself. But with fingers poking out of his eye sockets. And things coming out of his mouth. Like crab claws.”

I thought about people with crab legs coming out of their mouths, in mirrors. “Why did I find a shilling in my throat?”

“He wanted people to have money.”

“The opal miner? Who died in the car?”

“Yes. Sort of. Not exactly. He started this all off, like someone lighting a fuse on a firework. His death lit the touchpaper. The thing that’s exploding right now, that isn’t him. That’s somebody else. Something else.”

She rubbed her freckled nose with a grubby hand.

“A lady’s gone mad in that house,” she told me, and it would not have occurred to me to doubt her. “She has money in the mattress. Now she won’t get out of bed, in case someone takes it from her.”

“How do you know?”

She shrugged. “Once you’ve been around for a bit, you get to know stuff.”

I kicked a stone. “By ‘a bit’ do you mean ‘a really long time’?”

She nodded.

“How old are you, really?” I asked.

“Eleven.”

I thought for a bit. Then I asked, “How long have you been eleven for?”

She smiled at me.

We walked past Caraway Farm. The farmers, whom one day I would come to know as Callie Anders’s parents, were standing in their farmyard, shouting at each other. They stopped when they saw us.

When we rounded a bend in the lane, and were out of sight, Lettie said, “Those poor people.”

“Why are they poor people?”

“Because they’ve been having money problems. And this morning he had a dream where she . . . she was doing bad things. To earn money. So he looked in her handbag and found lots of folded-up ten-shilling notes. She says she doesn’t know where they came from, and he doesn’t believe her. He doesn’t know what to believe.”

“All the fighting and the dreams. It’s about money, isn’t it?”

“I’m not sure,” said Lettie, and she seemed so grown-up then that I was almost scared of her.

“Whatever’s happening,” she said, eventually, “it can all be sorted out.” She saw the expression on my face then, worried. Scared even. And she said, “After pancakes.”

Lettie cooked us pancakes on a big metal griddle, on the kitchen stove. They were paper-thin, and as each pancake was done Lettie would squeeze lemon onto it, and plop a blob of plum jam into the center, and roll it tightly, like a cigar. When there were enough we sat at the kitchen table and wolfed them down.

There was a hearth in that kitchen, and there were ashes still smoldering in the hearth, from the night before. That kitchen was a friendly place, I thought.

I said to Lettie, “I’m scared.”

She smiled at me. “I’ll make sure you’re safe. I promise. I’m not scared.”

I was still scared, but not as much. “It’s just scary.”

“I said I promise,” said Lettie Hempstock. “I won’t let you be hurt.”

“Hurt?” said a high, cracked voice. “Who’s hurt? What’s been hurt? Why would anybody be hurt?”

It was Old Mrs. Hempstock, her apron held between her hands, and in the hollow of the apron so many daffodils that the light reflected up from them transformed her face to gold, and the kitchen seemed bathed in yellow light.

Lettie said, “Something’s causing trouble. It’s giving people money. In their dreams and in real life.” She showed the old lady my shilling. “My friend found himself choking on this shilling when he woke up this morning.”

Old Mrs. Hempstock put her apron on the kitchen table, rapidly moved the daffodils off the cloth and onto the wood. Then she took the shilling from Lettie. She squinted at it, sniffed it, rubbed at it, listened to it (or put it to her ear, at any rate), then touched it with the tip of her purple tongue.

“It’s new,” she said, at last. “It says 1912 on it, but it didn’t exist yesterday.”

Lettie said, “I knew there was something funny about it.”

I looked up at Old Mrs. Hempstock. “How do you know?”

“Good question, luvvie. It’s electron decay, mostly. You have to look at things closely to see the electrons. They’re the little dinky ones that look like tiny smiles. The neutrons are the gray ones that look like frowns. The electrons were all a bit too smiley for 1912, so then I checked the sides of the letters and the old king’s head, and everything was a tad too crisp and sharp. Even where they were worn, it was as if they’d been made to be worn.”

“You must have very good eyesight,” I told her. I was impressed. She gave me back the coin.

“Not as good as it once was, but then, when you get to be my age, your eyesight won’t be as sharp as it once was, neither.” And she let out a guffaw as if she had said something very funny.

“How old is that?”

Lettie looked at me, and I was worried that I’d said something rude. Sometimes adults didn’t like to be asked their ages, and sometimes they did. In my experience, old people did. They were proud of their ages. Mrs. Wollery was seventy-seven, and Mr. Wollery was eighty-nine, and they liked telling us how old they were.

Old Mrs. Hempstock went over to a cupboard, and took out several colorful vases. “Old enough,” she said. “I remember when the moon was made.”

“Hasn’t there always been a moon?”

“Bless you. Not in the slightest. I remember the day the moon came. We looked up in the sky—it was all dirty brown and sooty gray here then, not green and blue . . .” She half-filled each of the vases at the sink. Then she took a pair of blackened kitchen scissors, and snipped off the bottom half-inch of stem from each of the daffodils.

I said, “Are you sure it’s not that man’s ghost doing this? Are you sure we aren’t being haunted?”

They both laughed then, the girl and the old woman, and I felt stupid. I said, “Sorry.”

“Ghosts can’t make things,” said Lettie. “They aren’t even good at moving things.”

Old Mrs. Hempstock said, “Go and get your mother. She’s doing laundry.” Then, to me, “You shall help me with the daffs.”

I helped her put the flowers into the vases, and she asked my opinion on where to put the vases in the kitchen. We placed the vases where I suggested, and I felt wonderfully important.

The daffodils sat like patches of sunlight, making that dark wooden kitchen even more cheerful. The floor was made of red and gray flagstones. The walls were whitewashed.

The old woman gave me a lump of honeycomb, from the Hempstocks’ own beehive, on a chipped saucer, and poured a little cream over it from a jug. I ate it with a spoon, chewing the wax like gum, letting the honey flow into my mouth, sweet and sticky with an aftertaste of wildflowers.

I was scraping the last of the cream and honey from the saucer when Lettie and her mother came into the kitchen. Mrs. Hempstock still had big Wellington boots on, and she strode in as if she were in an enormous hurry. “Mother!” she said. “Giving the boy honey. You’ll rot his teeth.”

Old Mrs. Hempstock shrugged. “I’ll have a word with the wigglers in his mouth,” she said. “Get them to leave his teeth alone.”

“You can’t just boss bacteria around like that,” said the younger Mrs. Hempstock. “They don’t like it.”

“Stuff and silliness,” said the old lady. “You leave wigglers alone and they’ll be carrying on like anything. Show them who’s boss and they can’t do enough for you. You’ve tasted my cheese.” She turned to me. “I’ve won medals for my cheese. Medals. Back in the old king’s day there were those who’d ride for a week to buy a round of my cheese. They said that the king himself had it with his bread and his boys, Prince Dickon and Prince Geoffrey and even little Prince John, they swore it was the finest cheese they had ever tasted—”

“Gran,” said Lettie, and the old lady stopped, mid-flow.

Lettie’s mother said, “You’ll be needing a hazel wand. And,” she added, somewhat doubtfully, “I suppose you could take the lad. It’s his coin, and it’ll be easier to carry if he’s with you. Something she made.”

“She?” said Lettie.

She was holding her horn-handled penknife, with the blade closed.

“Tastes like a she,” said Lettie’s mother. “I might be wrong, mind.”

“Don’t take the boy,” said Old Mrs. Hempstock. “Asking for trouble, that is.”

I was disappointed.

“We’ll be fine,” said Lettie. “I’ll take care of him. Him and me. It’ll be an adventure. And he’ll be company. Please, Gran?”

I looked up at Old Mrs. Hempstock with hope on my face, and waited.

“Don’t say I didn’t warn you, if it all goes wobbly,” said Old Mrs. Hempstock.

“Thank you, Gran. I won’t. And I’ll be careful.”

Old Mrs. Hempstock sniffed. “Now, don’t do anything stupid. Approach it with care. Bind it, close its ways, send it back to sleep.”

“I know,” said Lettie. “I know all that. Honestly. We’ll be fine.”

That’s what she said. But we weren’t.

Lettie led me to a hazel thicket beside the old road (the hazel catkins were hanging heavy in the spring) and she broke off a thin branch. Then, with her knife, as if she had done it ten thousand times before, she stripped the branch of bark, cut it again, so now it resembled a Y. She put the knife away (I did not see where it went) and held the two ends of the Y in her hands.

“I’m not dowsing,” she told me. “Just using it as a guide. We’re looking for a blue . . . a bluebottle, I think to start with. Or something purply-blue, and shiny.”

I looked around with her. “I can’t see one.”

“It’ll be here,” she assured me.

I gazed around, taking in the grass, a reddish-brown chicken pecking at the side of the driveway, some rusty farm machinery, the wooden trestle table beside the road and the six empty metal milk churns that sat upon it. I saw the Hempstocks’ red-brick farmhouse, crouched and comfortable like an animal at rest. I saw the spring flowers; the omnipresent white and yellow daisies, the golden dandelions and do-you-like-butter buttercups, and, late in the season, a lone bluebell in the shadows beneath the milk-churn table, still glistening with dew . . .

“That?” I asked.

“You’ve got sharp eyes,” she said, approvingly.

We walked together to the bluebell. Lettie closed her eyes when we reached it. She moved her body back and forth, the hazel wand extended, as if she were the central point on a clock or a compass, her wand the hands, orienting toward a midnight or an east that I could not perceive. “Black,” she said suddenly, as if she were describing something from a dream. “And soft.”

We walked away from the bluebell, along the lane that I imagined, sometimes, must have been a Roman road. We were a hundred yards up the lane, near where the Mini had been parked, when she spotted it: a scrap of black cloth caught on the barbed wire of the fence.

Lettie approached it. Again, the outstretched hazel stick, again the slow turning and turning. “Red,” she said, with certainty. “Very red. That way.”

We walked together in the direction she indicated. Across a meadow and into a clump of trees. “There,” I said, fascinated. The corpse of a very small animal—a vole, by the look of it—lay on a clump of green moss. It had no head, and bright blood stained its fur and beaded on the moss. It was very red.

“Now, from here on,” said Lettie, “hold on to my arm. Don’t let go.”

I put out my right hand and took her left arm, just below the elbow. She moved the hazel wand. “This way,” she said.

“What are we looking for now?”

“We’re getting closer,” she said. “The next thing we’re looking for is a storm.”

We pushed our way into a clump of trees, and through the clump of trees into a wood, and squeezed our way through trees too close together, their foliage a thick canopy above our heads. We found a clearing in the wood, and walked along the clearing, in a world made green.

From our left came a mumble of distant thunder.

“Storm,” sang Lettie. She let her body swing again, and I turned with her, holding her arm. I felt, or imagined I felt, a throbbing going through me, holding her arm, as if I were touching mighty engines.

She set off in a new direction. We crossed a tiny stream together. Then she stopped, suddenly, and stumbled, but did not fall.

“Are we there?” I asked.

“Not there,” she said. “No. It knows we’re coming. It feels us. And it does not want us to come to it.”

The hazel wand was whipping around now like a magnet being pushed at a repelling pole. Lettie grinned.

A gust of wind threw leaves and dirt up into our faces. In the distance I could hear something rumble, like a train. It was getting harder to see, and the sky that I could make out above the canopy of leaves was dark, as if huge storm-clouds had moved above our heads, or as if it had gone from morning directly to twilight.

Lettie shouted, “Get down!” and she crouched on the moss, pulling me down with her. She lay prone, and I lay beside her, feeling a little silly. The ground was damp.

“How long will we—?”

“Shush!” She sounded almost angry. I said nothing.

Something came through the woods, above our heads. I glanced up, saw something brown and furry, but flat, like a huge rug, flapping and curling at the edges, and, at the front of the rug, a mouth, filled with dozens of tiny sharp teeth, facing down.

It flapped and floated above us, and then it was gone.

“What was that?” I asked, my heart pounding so hard in my chest that I did not know if I would be able to stand again.

“Manta wolf,” said Lettie. “We’ve already gone a bit further out than I thought.” She got to her feet and stared the way the furry thing had gone. She raised the tip of the hazel wand, and turned around slowly.

“I’m not getting anything.” She tossed her head, to get the hair out of her eyes, without letting go of the fork of hazel wand. “Either it’s hiding or we’re too close.” She bit her lip. Then she said, “The shilling. The one from your throat. Bring it out.”

I took it from my pocket with my left hand, offered it to her.

“No,” she said. “I can’t touch it, not right now. Put it down on the fork of the stick.”

I didn’t ask why. I just put the silver shilling down at the intersection of the Y. Lettie stretched her arms out, and turned very slowly, with the end of the stick pointing straight out. I moved with her, but felt nothing. No throbbing engines. We were over halfway around when she stopped and said, “Look!”

I looked in the direction she was facing, but I saw nothing but trees, and shadows in the wood.

“No, look. There.” She indicated with her head.

The tip of the hazel wand had begun smoking, softly. She turned a little to the left, a little to the right, a little further to the right again, and the tip of the wand began to glow a bright orange.

“That’s something I’ve not seen before,” said Lettie. “I’m using the coin as an amplifier, but it’s as if—”

There was a whoompf! and the end of the stick burst into flame. Lettie pushed it down into the damp moss. She said, “Take your coin back,” and I did, picking it up carefully, in case it was hot, but it was icy cold. She left the hazel wand behind on the moss, the charcoal tip of it still smoking irritably.

Lettie walked and I walked beside her. We held hands now, my right hand in her left. The air smelled strange, like fireworks, and the world grew darker with every step we took into the forest.

“I said I’d keep you safe, didn’t I?” said Lettie.

“Yes.”

“I promised I wouldn’t let anything hurt you.”

“Yes.”

She said, “Just keep holding my hand. Don’t let go. Whatever happens, don’t let go.”

Her hand was warm, but not sweaty. It was reassuring.

“Hold my hand,” she repeated. “And don’t do anything unless I tell you. You’ve got that?”