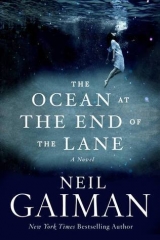

Текст книги "The ocean at the end of the lane"

Автор книги: Neil Gaiman

Жанры:

Современная проза

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 10 страниц)

I tried not to think.

I climbed over the brick wall that edged the balcony, reached out until I felt the iron drainpipe, cold and slick with rain. I held on to it, then took one large step toward it, letting my bare feet come to rest on the metal clamp that encircled the drainpipe, fixing it sturdily to the brick.

I went down, a step at a time, imagining myself Batman, imagining myself a hundred heroes and heroines of school romances, then, remembering myself, I imagined that I was a drop of rain on the wall, a brick, a tree. I am on my bed, I thought. I was not here, with the light of the TV room, uncurtained, spilling out below me, making the rain that fell past the window into a series of glittering lines and streaks.

Don’t look at me, I thought. Don’t look out of the window.

I inched down. Usually I would have stepped from the drainpipe over to the TV room’s outer window ledge, but that was out of the question. Warily, I lowered myself another few inches, leaned further back into the shadows and away from the light, and I stole a terrified glance into the room, expecting to see my father and Ursula Monkton staring back at me.

The room was empty.

The lights were on, the television on as well, but nobody was sitting on the sofa and the door to the downstairs hallway was open.

I took an easy step down onto the window ledge, hoping against all hope that neither of them would come back in and see me, then I let myself drop from the ledge into the flower bed. The wet earth was soft against my feet.

I was going to run, just run, but there was a light on in the drawing room, where we children never went, the oak-paneled room kept only for best and for special occasions.

The curtains were drawn. The curtains were green velvet, lined with white, and the light that escaped them, where they had not been closed all the way, was golden and soft.

I walked over to the window. The curtains were not completely closed. I could see into the room, see what was immediately in front of me.

I was not sure what I was looking at. My father had Ursula Monkton pressed up against the side of the big fireplace in the far wall. He had his back to me. She did too, her hands pressed against the huge, high mantelpiece. He was hugging her from behind. Her midi skirt was hiked up around her waist.

I did not know exactly what they were doing, and I did not really care, not at that moment. All that mattered was that Ursula Monkton had her attention on something that was not me, and I turned away from the gap in the curtains and the light and the house, and I fled, barefoot, into the rainy dark.

It was not pitch-black. It was the kind of cloudy night where the clouds seem to gather up light from distant streetlights and houses below, and throw it back at the earth. I could see enough, once my eyes adjusted. I made it to the bottom of the garden, past the compost heap and the grass cuttings, then down the hill to the lane. Brambles and thorns stuck my feet and pricked my legs, but I kept running.

I went over the low metal fence, into the lane. I was off our property and it felt as if a headache I had not known that I had had suddenly lifted. I whispered, urgently, “Lettie? Lettie Hempstock?” and I thought, I’m in bed. I’m dreaming all this. Such vivid dreams. I am in my bed, but I did not believe that Ursula Monkton was thinking about me just then.

As I ran, I thought of my father, his arms around the housekeeper-who-wasn’t, kissing her neck, and then I saw his face through the chilly bathwater as he held me under, and now I was no longer scared by what had happened in the bathroom; now I was scared by what it meant that my father was kissing the neck of Ursula Monkton, that his hands had lifted her midi skirt above her waist.

My parents were a unit, inviolate. The future had suddenly become unknowable: anything could happen: the train of my life had jumped the rails and headed off across the fields and was coming down the lane with me, then.

The flints of the lane hurt my feet as I ran, but I did not care. Soon enough, I was certain, the thing that was Ursula Monkton would be done with my father. Perhaps they would go upstairs to check on me together. She would find that I was gone and she would come after me.

I thought, If they come after me, they will be in a car. I looked for a gap in the hedgerow on either side of the lane. I spotted a wooden stile and clambered over it, and kept running across the meadow, heart pounding like the biggest loudest drum there was or had ever been, barefoot, with my pajamas and my dressing gown all soaked below the knee and clinging. I ran, not caring about the cow-pats. The meadow was easier on my feet than the flint lane had been. I was happier, and I felt more real, running on the grass.

Thunder rumbled behind me, although I had seen no lightning. I climbed a fence, and my feet sank into the soft earth of a freshly plowed field. I stumbled across it, falling sometimes, but I kept going. Over a stile and into the next field, this one unplowed, and I crossed it, keeping close to the hedge, scared of being too far out in the open.

The lights of a car came down the lane, sudden and blinding. I froze where I was, closed my eyes, imagined myself asleep in my bed. The car drove past without slowing, and I caught a glimpse of its rear red lights as it moved away from me: a white van, that I thought belonged to the Anders family.

Still, it made the lane seem less safe, and now I cut away across the meadow. I reached the next field, saw it was only divided from the one I was in by thin lengths of wire, easy to duck beneath, not even barbed wire, so I reached out my arm and pushed a bare wire up to make room to squeeze under, and—

It was as if I had been thumped, and thumped hard, in the chest. My arm, where it had grasped the wire of the fence, was convulsed, and my palm was burning as if I had just slammed my funny bone into a wall.

I let go of the electric fence and stumbled back. I could not run any longer, but I hurried in the wind and the rain and the darkness along the side of the fence, careful now not to touch it, until I reached a five-bar gate. I went over the gate, and across the field, heading to the deeper darkness at the far end—trees, I thought, and woodland—and I did not go too close to the edge of the field in case there was another electric fence waiting for me.

I hesitated, uncertain where to go next. As if in answer, the world was illuminated, for a moment, but I only needed a moment, by lightning. I saw a wooden stile, and I ran for it.

Over the stile. I came down into a clump of nettles, I knew, as the hot-cold pricking burning covered my exposed ankles and the tops of my feet, but I ran again, now, ran as best I could. I hoped I was still heading for the Hempstocks’ farm. I had to be. I crossed one more field before I realized that I no longer knew where the lane was, or for that matter, where I was. I knew only that the Hempstocks’ farm was at the end of my lane, but I was lost in a dark field, and the thunderclouds had lowered, and the night was so dark, and it was still raining, even if it was not raining hard yet, and now my imagination filled the darkness with wolves and ghosts. I wanted to stop imagining, to stop thinking, but I could not.

And behind the wolves and the ghosts and the trees that walked, there was Ursula Monkton, telling me that the next time I disobeyed her it would be so much worse for me, that she would lock me in the attic.

I was not brave. I was running away from everything, and I was cold, and wet and lost.

I shouted, at the top of my voice, “Lettie? Lettie Hempstock! Hello?” but there was no reply, and I had not expected one.

The thunder grumbled and rumbled into a low continuous roar, a lion pushed into irritability, and the lightning was flashing and flickering like a malfunctioning fluorescent tube. In the flickers of light, I could see that the area of field I was in came to a point, with hedges on both sides, and no way through. I could see no gate, and no stile other than the one I had come in through, at the far end of the field.

Something crackled.

I looked up at the sky. I had seen lightning in films on the television, long jagged forks of light across the clouds. But the lightning I had seen until now with my own eyes was simply a white flash from above, like the flash of a camera, burning the world in a strobe of visibility. What I saw in the sky then was not that.

It was not forked lightning either.

It came and it went, a writhing, burning blue-whiteness in the sky. It died back and then it flared up, and its flares and flickers illuminated the meadow, made it something I could see. The rain pattered hard, and it whipped against my face, moved in a moment from a drizzle to a downpour. In seconds my dressing gown was soaked through. But in the light I saw—or thought I saw—an opening in the hedgerow to my right, and I walked, for I could no longer run, not any longer, as fast as I could, toward it, hoping it was something real. My wet gown flapped in the gusting wind, and the sound of the flapping cloth horrified me.

I did not look up in the sky. I did not look behind me.

But I could see the far end of the field, and there was indeed a space between the hedgerows. I had almost reached it when a voice said,

“I thought I told you to stay in your room. And now I find you sneaking around like a drowned sailor.”

I turned, looked behind me, saw nothing at all. There was nobody there.

Then I looked up.

The thing that called itself Ursula Monkton hung in the air, about twenty feet above me, and lightnings crawled and flickered in the sky behind her. She was not flying. She was floating, weightless as a balloon, although the sharp gusts of wind did not move her.

Wind howled and whipped at my face. The distant thunder roared and smaller thunders crackled and spat, and she spoke quietly, but I could hear every word she said as distinctly as if she were whispering into my ears.

“Oh, sweety-weety-pudding-and-pie, you are in so much trouble.”

She was smiling, the hugest, toothiest grin I had ever seen on a human face, but she did not look amused.

I had been running from her through the darkness for, what, half an hour? An hour? I wished I had stayed on the lane and not tried to cut across the fields. I would have been at the Hempstocks’ farm by now. Instead, I was lost and I was trapped.

Ursula Monkton came lower. Her pink blouse was open and unbuttoned. She wore a white bra. Her midi skirt flapped in the wind, revealing her calves. She did not appear to be wet, despite the storm. Her clothes, her face, her hair, were perfectly dry.

She was floating above me, now, and she reached out her hands.

Every move she made, everything she did, was strobed by the tame lightnings that flickered and writhed about her. Her fingers opened like flowers in a speeded-up film, and I knew that she was playing with me, and I knew what she wanted me to do, and I hated myself for not standing my ground, but I did what she wanted: I ran.

I was a little thing that amused her. She was playing, just as I had seen Monster, the big orange tomcat, play with a mouse—letting it go, so that it would run, and then pouncing, and batting it down with a paw. But the mouse still ran, and I had no choice, and I ran too.

I ran for the break in the hedge, as fast as I could, stumbling and hurting and wet.

Her voice was in my ears as I ran.

“I told you I was going to lock you in the attic, didn’t I? And I will. Your daddy likes me now. He’ll do whatever I say. Perhaps from now on, every night, he’ll come up the ladder and let you out of the attic. He’ll make you climb down from the attic. Down the ladder. And every night, he’ll drown you in the bath, he’ll plunge you into the cold, cold water. I’ll let him do it every night until it bores me, and then I’ll tell him not to bring you back, to simply push you under the water until you stop moving and until there’s nothing but darkness and water in your lungs. I’ll have him leave you in the cold bath, and you’ll never move again. And every night I’ll kiss him and kiss him . . .”

I was through the gap in the hedgerow, and running on soft grass.

The crackle of the lightning, and a strange sharp, metallic smell, were so close they made my skin prickle. Everything around me got brighter and brighter, illuminated by the flickering blue-white light.

“And when your daddy finally leaves you in the bath for good, you’ll be happy,” whispered Ursula Monkton, and I imagined that I could feel her lips brushing my ears. “Because you won’t like it in the attic. Not just because it’s dark up there, with the spiders, and the ghosts. But because I’m going to bring my friends. You can’t see them in the daylight, but they’ll be in the attic with you, and you won’t enjoy them at all. They don’t like little boys, my friends. They’ll pretend to be spiders as big as dogs. Old clothes with nothing inside that tug at you and never let you go. The inside of your head. And when you’re in the attic there will be no books, and no stories, not ever again.”

I had not imagined it. Her lips had brushed my ear. She was floating in the air beside me, so her head was beside mine, and when she caught me looking at her she smiled her pretend-smile, and I could not run any longer. I could barely move. I had a stitch in my side, and I could not catch my breath, and I was done.

My legs gave way beneath me, and I stumbled and fell, and this time I did not get up.

I felt heat on my legs, and I looked down to see a yellow stream coming from the front of my pajama trousers. I was seven years old, no longer a little child, but I was wetting myself with fear, like a baby, and there was nothing I could do about it, while Ursula Monkton hung in the air a few feet above me and watched, dispassionately.

The hunt was done.

She stood up straight in the air, three feet above the ground. I was sprawled beneath her, on my back, in the wet grass. She began to descend, slowly, inexorably, like a person on a broken television screen.

Something touched my left hand. Something soft. It nosed my hand, and I looked over, fearing a spider as big as a dog. Illuminated by the lightnings that writhed about Ursula Monkton, I saw a patch of darkness beside my hand. A patch of darkness with a white spot over one ear. I picked the kitten up in my hand, and brought it to my heart, and I stroked it.

I said, “I won’t come with you. You can’t make me.” I sat up, because I felt less vulnerable sitting, and the kitten curled and made itself comfortable in my hand.

“Pudding-and-pie boy,” said Ursula Monkton. Her feet touched the ground. She was illuminated by her own lightnings, like a painting of a woman in grays and greens and blues, and not a real woman at all. “You’re just a little boy. I’m a grown-up. I was an adult when your world was a ball of molten rock. I can do whatever I wish to you. Now, stand up. I’m taking you home.”

The kitten, which was burrowing into my chest with its face, made a high-pitched noise, not a mew. I turned, looking away from Ursula Monkton, looking behind me.

The girl who was walking toward us, across the field, wore a shiny red raincoat, with a hood, and a pair of black Wellington boots that seemed too big for her. She walked out of the darkness, unafraid. She looked up at Ursula Monkton.

“Get off my land,” said Lettie Hempstock.

Ursula Monkton took a step backwards and she rose, at the same time, so she hung in the air above us. Lettie Hempstock reached out to me, without glancing down at where I sat, and she took my hand, twining her fingers into mine.

“I’m not touching your land,” said Ursula Monkton. “Go away, little girl.”

“You are on my land,” said Lettie Hempstock.

Ursula Monkton smiled, and the lightnings wreathed and writhed about her. She was power incarnate, standing in the crackling air. She was the storm, she was the lightning, she was the adult world with all its power and all its secrets and all its foolish casual cruelty. She winked at me.

I was a seven-year-old boy, and my feet were scratched and bleeding. I had just wet myself. And the thing that floated above me was huge and greedy, and it wanted to take me to the attic, and, when it tired of me, it would make my daddy kill me.

Lettie Hempstock’s hand in my hand made me braver. But Lettie was just a girl, even if she was a big girl, even if she was eleven, even if she had been eleven for a very long time. Ursula Monkton was an adult. It did not matter, at that moment, that she was every monster, every witch, every nightmare made flesh. She was also an adult, and when adults fight children, adults always win.

Lettie said, “You should go back where you came from in the first place. It’s not healthy for you to be here. For your own good, go back.”

A noise in the air, a horrible, twisted scratching noise, filled with pain and with wrongness, a noise that set my teeth on edge and made the kitten, its front paws resting on my chest, stiffen and its fur prickle. The little thing twisted and clawed up onto my shoulder, and it hissed and it spat. I looked up at Ursula Monkton. It was only when I saw her face that I knew what the noise was.

Ursula Monkton was laughing.

“Go back? When your people ripped the hole in Forever, I seized my chance. I could have ruled worlds, but I followed you, and I waited, and I had patience. I knew that sooner or later the bounds would loosen, that I would walk the true Earth, beneath the Sun of Heaven.” She was not laughing now. “Everything here is so weak, little girl. Everything breaks so easily. They want such simple things. I will take all I want from this world, like a child stuffing its fat little face with blackberries from a bush.”

I did not let go of Lettie’s hand, not this time. I stroked the kitten, whose needle-claws were digging into my shoulder, and I was bitten for my trouble, but the kitten’s bite was not hard, just scared.

Her voice came from all around us, as the storm-wind gusted. “You kept me away from here for a long time. But then you brought me a door, and I used him to carry me out of my cell. And what can you do now that I am out?”

Lettie didn’t seem angry. She thought about it, then she said, “I could make you a new door. Or, better still, I could get Granny to send you across the ocean, all the way to wherever you came from in the beginning.”

Ursula Monkton spat onto the grass, and a tiny ball of flame sputtered and fizzed on the ground, where the spit had fallen.

“Give me the boy,” was all she said. “He belongs to me. I came here inside him. I own him.”

“You don’t own nuffink, you don’t,” said Lettie Hempstock, angrily. “ ’Specially not him.” Lettie helped me to my feet, and she stood behind me and put her arms around me. We were two children in a field in the night. Lettie held me, and I held the kitten, while above us and all around us a voice said,

“What will you do? Take him home with you? This world is a world of rules, little girl. He belongs to his parents, after all. Take him away and his parents will come to bring him home, and his parents belong to me.”

“I’m all bored of you now,” said Lettie Hempstock. “I gived you a chance. You’re on my land. Go away.”

As she said that, my skin felt like it did when I’d rubbed a balloon on my sweater, then touched it to my face and hair. Everything prickled and tickled. My hair was soaked, but even wet, it felt like it was starting to stand on end.

Lettie Hempstock held me tightly. “Don’t worry,” she whispered, and I was going to say something, to ask why I shouldn’t worry, what I had to be afraid of, when the field we were standing in began to glow.

It glowed golden. Every blade of grass glowed and glimmered, every leaf on every tree. Even the hedges were glowing. It was a warm light. It seemed, to my eyes, as if the soil beneath the grass had transmuted from base matter into pure light, and in the golden glow of the meadow the blue-white lightnings that still crackled around Ursula Monkton seemed much less impressive.

Ursula Monkton rose unsteadily, as if the air had just become hot and was carrying her upwards. Then Lettie Hempstock whispered old words into the world and the meadow exploded into a golden light. I saw Ursula Monkton swept up and away, although I felt no wind, but there had to be a wind, for she was flailing and tipping like a dead leaf in a gale. I watched her tumble into the night, and then Ursula Monkton and her lightnings were gone.

“Come on,” said Lettie Hempstock. “We should get you in front of a kitchen fire. And a hot bath. You’ll catch your death.” She let go of my hand, stopped hugging me, stepped back. The golden glow dimmed, so slowly, and then it was gone, leaving only vanishing glimmers and twinkles in the bushes, like the final moments of the fireworks on Bonfire Night.

“Is she dead?” I asked.

“No.”

“Then she’ll come back. And you’ll get in trouble.”

“That’s as may be,” said Lettie. “Are you hungry?”

She asked me, and I knew that I was. I had forgotten, somehow, but now I remembered. I was so hungry it hurt.

“Let’s see . . .” Lettie was talking as she led me through the fields. “You’re wet through. We’ll need to get you something to wear. I’ll have a look in the chest of drawers in the green bedroom. I think Cousin Japeth left some of his clothes there when he went off to fight in the Mouse Wars. He wasn’t much bigger than you.”

The kitten was licking my fingers with a small, rough tongue.

“I found a kitten,” I said.

“I can see that. She must have followed you back from the fields where you pulled her up.”

“This is that kitten? The same one that I picked?”

“Yup. Did she tell you her name, yet?”

“No. Do they do that?”

“Sometimes. If you listen.”

I saw the lights of the Hempstocks’ farm in front of us, welcoming, and I was cheered, although I could not understand how we had got from the field we were in to the farmhouse so quickly.

“You were lucky,” said Lettie. “Fifteen feet further back, and the field belongs to Colin Anders.”

“You would have come anyway,” I told her. “You would have saved me.”

She squeezed my arm with her hand but she said nothing.

I said, “Lettie. I don’t want to go home.” That was not true. I wanted to go home more than anything, just not to the place I had fled that night. I wanted to go back to the home I had lived in before the opal miner had killed himself in our little white Mini, or before he had run over my kitten.

The ball of dark fur pressed itself into my chest, and I wished she was my kitten, and knew that she was not. The rain had become a drizzle once again.

We splashed through deep puddles, Lettie in her Wellington boots, my stinging feet bare. The smell of manure was sharp in the air as we reached the farmyard, and then we walked through a side door and into the huge farmhouse kitchen.

Lettie’s mother was prodding the huge fireplace with a poker, pushing the burning logs together.

Old Mrs. Hempstock was stirring a bulbous pot on the stove with a large wooden spoon. She lifted the spoon to her mouth, blew on it theatrically, sipped from it, pursed her lips, then added a pinch of something and a fistful of something else to it. She turned down the flame. Then she looked at me, from my wet hair to my bare feet, which were blue with cold. As I stood there a puddle began to appear on the flagstone floor around me, and the drips of water from my dressing gown splashed into it.

“Hot bath,” said Old Mrs. Hempstock. “Or he’ll catch his death.”

“That was what I said,” said Lettie.

Lettie’s mother was already hauling a tin bath from beneath the kitchen table, and filling it with steaming water from the enormous black kettle that hung above the fireplace. Pots of cold water were added until she pronounced it the perfect temperature.

“Right. In you go,” said Old Mrs. Hempstock. “Spit-spot.”

I looked at her, horrified. Was I going to have to undress in front of people I didn’t know?

“We’ll wash your clothes, and dry them for you, and mend that dressing gown,” said Lettie’s mother, and she took the dressing gown from me, and she took the kitten, which I had barely realized I was still holding, and then she walked away.

As quickly as possible I shed my red nylon pajamas—the bottoms were soaked and the legs were now ragged and ripped and would never be whole again. I dipped my fingers into the water, then I climbed in and sat down on the tin floor of the bath in that reassuring kitchen in front of the huge fire, and I leaned back in the hot water. My feet began to throb as they came back to life. I knew that naked was wrong, but the Hempstocks seemed indifferent to my nakedness: Lettie was gone, and my pajamas and dressing gown with her; her mother was getting out knives, forks, spoons, little jugs and bigger jugs, carving knives and wooden trenchers, and arranging them about the table.

Old Mrs. Hempstock passed me a mug, filled with soup from the black pot on the stove. “Get that down you. Heat you up from the inside, first.”

The soup was rich, and warming. I had never drunk soup in the bath before. It was a perfectly new experience. When I finished the mug I gave it back to her, and in return she passed me a large cake of white soap and a face-flannel and said, “Now get scrubbin’. Rub the life and the warmth back into your bones.”

She sat down in a rocking chair on the other side of the fire, and rocked gently, not looking at me.

I felt safe. It was as if the essence of grandmotherliness had been condensed into that one place, that one time. I was not at all afraid of Ursula Monkton, whatever she was, not then. Not there.

Young Mrs. Hempstock opened an oven door and took out a pie, its shiny crust brown and glistening, and put it on the window ledge to cool.

I dried myself off with a towel they brought me, the fire’s heat drying me as much as the towel did, then Lettie Hempstock returned and gave me a voluminous white thing, like a girl’s nightdress but made of white cotton, with long arms, and a skirt that draped to the floor, and a white cap. I hesitated to put it on until I realized what it was: a nightgown. I had seen pictures of them in books. Wee Willie Winkie ran through the town wearing one in every book of nursery rhymes I had ever owned.

I slipped into it. The nightcap was too big for me, and fell down over my face, and Lettie took it away once more.

Dinner was wonderful. There was a joint of beef, with roast potatoes, golden-crisp on the outside and soft and white inside, buttered greens I did not recognize, although I think now that they might have been nettles, roasted carrots all blackened and sweet (I did not think that I liked cooked carrots, so I nearly did not eat one, but I was brave, and I tried it, and I liked it, and was disappointed in boiled carrots for the rest of my childhood). For dessert there was the pie, stuffed with apples and with swollen raisins and crushed nuts, all topped with a thick yellow custard, creamier and richer than anything I had ever tasted at school or at home.

The kitten slept on a cushion beside the fire, until the end of the meal, when it joined a fog-colored house cat four times its size in a meal of scraps of meat.

While we ate, nothing was said about what had happened to me, or why I was there. The Hempstock ladies talked about the farm—there was the door to the milking shed needed a new coat of paint, a cow named Rhiannon who looked to be getting lame in her left hind leg, the path to be cleared on the way that led down to the reservoir.

“Is it just the three of you?” I asked. “Aren’t there any men?”

“Men!” hooted Old Mrs. Hempstock. “I dunno what blessed good a man would be! Nothing a man could do around this farm that I can’t do twice as fast and five times as well.”

Lettie said, “We’ve had men here, sometimes. They come and they go. Right now, it’s just us.”

Her mother nodded. “They went off to seek their fate and fortune, mostly, the male Hempstocks. There’s never any keeping them here when the call comes. They get a distant look in their eyes and then we’ve lost them, good and proper. Next chance they gets they’re off to towns and even cities, and nothing but an occasional postcard to even show they were here at all.”

Old Mrs. Hempstock said, “His parents are coming! They’re driving here. They just passed Parson’s elm tree. The badgers saw them.”

“Is she with them?” I asked. “Ursula Monkton?”

“Her?” said Old Mrs. Hempstock, amused. “That thing? Not her.”

I thought about it for a moment. “They will make me go back with them, and then she’ll lock me in the attic and let my daddy kill me when she gets bored. She said so.”

“She may have told you that, ducks,” said Lettie’s mother, “but she en’t going to do it, or anything like it, or my name’s not Ginnie Hempstock.”

I liked the name Ginnie, but I did not believe her, and I was not reassured. Soon the door to the kitchen would open, and my father would shout at me, or he would wait until we got into the car, and he would shout at me then, and they would take me back up the lane to my house, and I would be lost.

“Let’s see,” said Ginnie Hempstock. “We could be away when they get here. They could arrive last Tuesday, when there’s nobody home.”

“Out of the question,” said the old woman. “Just complicates things, playing with time . . . We could turn the boy into something else, so they’d never find him, look how hard they might.”

I blinked. Was that even possible? I wanted to be turned into something. The kitten had finished its portion of meat-scraps (indeed, it seemed to have eaten more than the house cat) and now it leapt into my lap, and began to wash itself.

Ginnie Hempstock got up and went out of the room. I wondered where she was going.

“We can’t turn him into anything,” said Lettie, clearing the table of the last of the plates and cutlery. “His parents will get frantic. And if they are being controlled by the flea, she’ll just feed the franticness. Next thing you know, we’ll have the police dragging the reservoir, looking for him. Or worse. The ocean.”