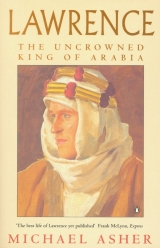

Текст книги "Lawrence: The Uncrowned King of Arabia"

Автор книги: Michael Asher

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 29 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

The end began in November, when Lawrence was moved suddenly from Uxbridge to the RAF School of Photography at Farnborough. At first he was delighted, and wrote to Swann that he had ‘almost burned down the camp with joy’ when the news of his transfer had arrived. When he reached his new posting, however, his mood quickly changed, for he discovered that the current photography course was already under way and that he would have to wait until January for the next one. He complained to Swann, making it clear that unless he could begin training as a photographer at once, he wished to be posted elsewhere. He confessed that he was glad to get away from Uxbridge because the physical side of the training had been knocking him up, but though Farnborough was by comparison ‘a jolly rest cure’ it was not the kind of RAF he wanted to write about, and without the photographic training he would simply be bored. For ten days he filled in as orderly in the Adjutant’s office, until an order came down from the Air Chief Marshal that AC 2 Ross must be put on the current course at once. By this time many of the staff of the School of Photography were aware of Ross’s ‘secret identity’, and the presence of an international celebrity posing rather half-heartedly in their midst as a lowly private naturally disturbed the officers, who suspected that he had been planted as some kind of Air Ministry spy. Lawrence continued to exhibit his self-imposed suffering to the gallery of high society, writing to E. M. Forster, for instance, that he ‘hated’ the ‘dirty living’ of the barrack-room, and could not bear to think of the years of poverty which stretched endlessly before him. He confessed that he was physically afraid of his colleagues, hated their noise and ‘animal spirits’, but insisted – as if begging contradiction – that he was exactly like them, declaring that he would not leave the RAF for any other job. The effect was rather like that of a man locking himself in a filthy prison-cell and crying through the bars that the conditions were terrible, but that this was where he really belonged and that he would do anything rather than come out. It is clear, however, that Lawrence was not as committed to remaining in the ranks as he maintained. Indeed, at Farnborough he started to become openly provocative with his officers – once, when a young subaltern criticized his turn-out, replying to him in Arabic or ancient Greek, making him a laughing, stock in front of the men. While Lawrence later claimed to have been ‘sold out’ to the press by one of his officers, it is much more likely that he deliberately exposed himself. In fact, he had begun giving away his pseudonym and address quite freely, and had even, in a fit of unadulterated self-destructiveness, written to R. D. Blumenfeld, editor of the Daily Express,giving full details of his enlistment and beseeching him not to reveal it to the public. This was asking too much of a professional newspaperman, and Blumenfeld may have realized that Lawrence was flashing a subliminal green light. He probably gave a tip-off to one of his reporters, for on 27 December 1922 the Expressprinted on its front page a story entitled Uncrowned King as Private Soldier,revealing Lawrence’s ‘hiding place’ to the world and making it impossible for him to continue in the RAF. In January 1923 – much to his apparent chagrin – he was obliged to leave. By this time, however, his disappointment was genuine, for in the meantime he had become romantically attached to an attractive blond-haired young airman named R. A. M. Guy, whose radiant good looks were likened by one of his colleagues to those of a ‘Greek god’. Lawrence himself called Guy ‘angelic’ but noted snobbishly that his beauty was marred by his ‘vile’ Brummie accent – as if Greek gods had naturally spoken Oxford English. Just as Lawrence had seen his attachment to the Arab cause partly as an expression of his relationship with the ‘noble’ Dahoum, so his admiration for the air force as an organization began to grow through his idealization of Guy. He thought Guy embodied all that was best in its ranks, and was soon waxing enthusiastic about the infinite superiority of the young men in the RAF to those in the army. Though his relationship with Guy was probably as platonic as his association with Dahoum, they were becoming emotionally intimate when they were forced to split up: ‘You and me, we’re very un-matched,’ Lawrence wrote to Guy later, ‘and it took some process as slow and kindly and persistent as the barrack-room communism to weld us comfortably together. People aren’t friends till they have said all they can say, and are able to sit together, at work or rest, hour-long without speaking… We never got quite to that, but we were nearer it daily … and since S.A. died I haven’t experienced any risk of that happening.’ 19

Lawrence appealed for reinstatement to Trenchard and Minister of Air Sam Hoare, but his credit had expired. His status-games were fun for him, but detrimental to the good order of the RAF, and Trenchard would reconsider only if he agreed to take a commission, which for Lawrence would have spoiled the effect completely. By February, however, he had succeeded in pulling strings at the War Office, and with the help of Alan Dawnay, his wartime colleague from Hedgehog, and General Sir Philip Chetwode, who had commanded the Desert Column in Palestine, managed to enlist again, this time as a private in the Royal Tank Corps. In March, Lawrence signed on in the army for seven years at Bovington Camp, Dorset, under yet another pseudonym: T. E. Shaw. This time, however, he did not enter the ranks alone, for when he walked into the guard-room at Bovington he was escorted by a tall, tough-looking young Scotsman named John Bruce, who had joined the army with him to act as his personal minder.

Lawrence had met Bruce in London in 1922, while still working for the Colonial Office, at the Mayfair flat of a man called Edward Murray, who was considering the eighteen-year-old Scotsman for a job. On their second meeting, Lawrence told Bruce who he was, and informed him that he was looking for someone who was young, strong and alert, who could be trusted with highly confidential personal matters. Bruce thought him a crank, and protested that he was not qualified, but he was desperately in need of a job, and Lawrence offered him a generous salary of Ј3 a month as a retainer. On subsequent meetings Lawrence swore Bruce to the utmost confidence, and began to unfold a long and complicated fantasy, claiming to be in the power of a relative he referred to as the ‘Old Man’. The story went that he was in debt and, under pressure from his bank, had decided to write a book, hoping that it would make enough money to allow him to pay off his debt and retire to the country. He had applied to a merchant bank for the money to live on while the book was being written, and the bank had asked for the copyright of the book, and requested a guarantor. He said that when his father had died in 1919, the Old Man had inherited his money, and Lawrence had asked him to act as his guarantor. At first he had agreed, but when he discovered that Lawrence had quit his job with the Colonial Office, he had changed his mind, called Lawrence a ‘bastard’ and accused him of a plethora of sins, including insulting King George at Buckingham Palace, ruining the career of Lord Curzon, turning his back on God, and dragging the family name through the gutter. The Old Man, said Lawrence, had agreed to take over his financial affairs and handle his debts, but only on the understanding that all ‘disciplinary matters’ were to be placed in his hands: if he did not agree the Old Man would expose the circumstances of his birth. His life was to be strictly curtailed: he was to enlist in the army or the RAF as a private, and spend his time either writing or soldiering. The only friends he was to be allowed in the ‘upper bracket’ were people connected with his writing. Lawrence told Bruce that he had sworn on the Bible to respect the Old Man’s every wish, and mentioned that corporal punishment might be involved. 20Bruce was suspicious, not because he disbelieved the story, but because he and Lawrence were poles apart socially and he wondered why Lawrence had chosen him for this particular job. Lawrence explained that most of his ‘friends’ couldn’t be trusted, and the few who could were ‘too big’. They would be willing to help only for personal gain: ‘you don’t know what is to be gained,’ Lawrence told him, ‘and wouldn’t be disappointed if you gained nothing.’ 21He sent Bruce back to Aberdeen, telling him that he would be called for when needed.

While Lawrence was at Uxbridge and Farnborough, he corresponded with Bruce occasionally, telling him how much he loathed the RAF, but hinting that the Old Man thought the life too soft: he had no right to be there at all, he wrote, since the Old Man had arranged for him to join the army. In November Lawrence asked Bruce to come to Farnborough, and when they met informed him that ‘a birch had arrived’ and that the Old Man wanted him to ‘take a few over the buttocks’ as a penalty for having ‘cheated him’ in joining the RAF instead of the army. Before the ‘punishment’ could be carried out, however, Lawrence was exposed by the press in his guise of ‘Ross’ and obliged to leave. He told Bruce that the Old Man had paid an officer at Farnborough Ј30 to give the story to the Express.Bruce temporarily lost touch with him, but in January 1923 he moved to London and managed to get a job as a bouncer in a Paddington nightclub, leaving a message for Lawrence at his borrowed Barton Street flat. A few days later Lawrence came to see him, looking dirty, ragged, sick and exhausted, telling him he had been sleeping rough for several nights (in fact he had been sleeping in the sidecar of the motorcycle he had acquired while in the RAF). Lawrence told Bruce that the Old Man was now forcing him to join the Royal Tank Corps. According to Bruce, he then volunteered to join the army with Lawrence.

*

It seems likely that someone in the military authorities knew of the association between Lawrence and Bruce, for Bruce recounted that his recruitment in Aberdeen had been pre-arranged. Lawrence told him that his offer had pleased the Old Man, who would be writing to him directly once they had enlisted. At Bovington they were given consecutive serial numbers, and adjoining beds in the same hut. They were issued with ill-fitting uniforms, and assigned to a squad of twenty-two recruits, for the duration of their sixteen weeks’ training: ‘we had everyone in the hut sized up,’ Bruce wrote. ‘It was the bad ones I had to keep my eyes on, especially the drinkers, who were continually touching Lawrence for money … I came into the hut and heard a fellow giving Lawrence a mouthful of filth because he refused to give him a pound. I jumped him there and then and one hell of a fight took place … 22Shortly afterwards, Lawrence rented Clouds Hill, a cottage which stood close to the camp, as a refuge from the almost intolerable life of the barrack-room, and it was here, in 1923, that Bruce gave Lawrence a birching for the first time. The beating was arranged with the precision of a ritual. First, Lawrence told Bruce that the Old Man had decided he must be punished, and had sentenced him to twelve strokes of the birch. He then handed Bruce a typed letter, purporting to be from the Old Man, which informed him that he was to pick up a birch from the local railway-station and administer the punishment, afterwards reporting to him in writing that he had done so, and describing how Lawrence had conducted himself throughout the beating. At first, Bruce declared that he would have nothing to do with it, but Lawrence insisted that it had to be done. Since Lawrence seemed to be willing, Bruce finally agreed, and carried out the ‘sentence’ the same afternoon. However, since Lawrence kept his trousers on during the birching – which consisted of twelve strokes to the buttocks – the Old Man was not appeased, and the thrashing had to be repeated later, on Lawrence’s bare behind: ‘After I had given him the twelve, he said: “Give me another one for luck,”‘ Bruce remembered. ‘It is nasty. The prongs go into the skin and break the blood vessels and it bleeds. He just lay there and gritted his teeth. He never moved.’ 23Whether this was the first such birching Lawrence had ever received is open to question. Curiously, Bruce stated that he saw ‘no other scars’, though W. E. Johns claimed to have seen ‘a mass of recent scars’ on Lawrence’s back at the recruiting office less than a year earlier. Bruce also said that he was not the only man to have beaten Lawrence in this manner – indeed, some time later he discovered birch-marks on Lawrence’s legs while they were working out in a gymnasium in Bournemouth, and Lawrence told him they had been inflicted by ‘an employee of the Old Man’. 24Between 1923 and 1935, Bruce birched Lawrence on nine occasions, at Clouds Hill, at Barton Street, at his home in Aberdeen and at other places in Scotland, and on at least one occasion another witness was present. Moreover, Philip Knightley and Colin Simpson, the Sunday Timesreporters to whom Bruce told his story, revealed in their 1968 article that they knew of two other men who had been employed to thrash Lawrence, though whether before, after, or concurrently with Bruce is unknown. If Johns did see ‘recent’ scars on Lawrence’s back in 1922, then it may be that Lawrence’s flagellation disorder had begun before he met Bruce earlier that year. However, it is likely that Johns’s statement was spurious: Bruce’s beatings were always administered to the buttocks rather than the back, suggesting a sexual element which some biographers have tried to suppress, and which was confirmed by Bruce’s admission that Lawrence sometimes experienced orgasm as a result of the floggings. The attempt of some biographers to ‘sanctify’ Lawrence’s masochism by suggesting that he tried to emulate the practices of medieval saints also falls down on this point – for medieval flagellants were invariably whipped on the back rather than the buttocks.

Some have maintained that this disorder was created by Lawrence’s experience at Dara’a. However, while we have no corroborating evidence that Lawrence was captured and beaten by the Turks in 1917, we do know for certain that he was beaten severely on the buttocks by Sarah as a child, and that he showed distinct masochistic tendencies as a youth. The flagellation disorder, indeed, was the culmination of a life which was dominated by masochistic and self-degrading fantasies both social and physical, and its foundations lie not in Dara’a – whatever did or did not happen there – but in Lawrence’s relationship with his mother during his earliest years. Dara’a – fantasy or reality – is simply one expression of a process which may be traced directly from Polstead Road in the 1890s to Clouds Hill in 1923. What is interesting about the Bruce story, however, is the light it sheds on some other aspects of Lawrence’s character. The edifice of fantasy he told Bruce was a calculated lie from beginning to end, yet he unfolded it in astonishing and consistent detail. He invented the ‘Old Man’ and had him ‘corresponding’ with Bruce, sending him dozens of letters which he had actually written himself. Bruce liked and admired Lawrence and was proud to have been able to help him. Even after Lawrence’s death the Scotsman refused to believe that he had ever told him a deliberate lie, and remained convinced, fifty years later, that the Old Man had actually existed. He was perhaps naпve and inexperienced, bemused by Lawrence’s rhetoric and dazzled by his intellect, but he was not stupid. It is a superlative comment on Lawrence’s powers of invention, manipulation and persuasion that he was able to convince another human being of the actual existence of a character he had simply made up, and maintain the fantasy over a period of thirteen years without once giving himself away. Of his ‘Old Man’ story, Arnie wrote to John Mack: ‘From my slight experience of psychological warfare (of which T.E. had plenty) an elaborate fiction is more plausible the nearer it comes to fact, although the fact is unknowable to the audience; hence he [Lawrence] gives his lies a garbled foundation of fact…’ 25It does not seem to have occurred either to Arnie or to his correspondent Mack that Lawrence may have told lies based on garbled fact at other times in his life too – for instance when describing the alleged Dara’a incident. Neither did it occur to Arnie that in this case Lawrence was not fighting the Turks, but taking in a good-natured and trusting young man, who believed him to be honest and devoted a major part of his life to helping him. Though, throughout these years, Lawrence had conspicuous, high-profile ‘friendships’ with famous men such as Thomas Hardy, Bernard Shaw, E. M. Forster, Robert Graves and many others, it was John Bruce, an uneducated young Scotsman, with whom he felt truly ‘safe’. Bruce remained close to Lawrence for the rest of his life, but after his death was sneered at by Arnie and Bob, and treated as if it was he who had victimized Lawrence. Even Charlotte Shaw joined in the conspiracy and tried to silence him: ‘they were prepared to go to any lengths,’ Bruce wrote, ‘to see that the reason for our association did not become public property … They were so impressed with their own importance, that they thought I was going to be an easy nut to crack … Had they been successful then this story would never have been told.’ 26

Bruce was unhappy in the army and soon left, though he and Lawrence were to meet at intervals thereafter. Lawrence himself could not settle down in the Tanks, and pined for the RAF. He wrote letters to Trenchard and Hoare whose tone became increasingly strident, until he began to mention suicide. Once, while a guest at Trenchard’s house during his time in the Tank Corps, he threatened to ‘end it all’ there and then, upon which Trenchard smiled and asked him if he wouldn’t mind doing it in the garden as he did not want his carpets ruined. On another occasion at Clouds Hill, Bruce had to jerk a pistol out of Lawrence’s hand by banging it repeatedly against the wall, when he declared his intention to shoot himself. Afterwards, Bruce recalled, Lawrence burst into tears. His discontent was not with the army, but with himself, and his need always to ‘seek his pleasures downwards’. Nevertheless, he had his sights set on the RAF again, and in June 1925 he wrote to Edward Garnett: ‘I’m no bloody good on earth. So I’m going to quit: but in my usual comic fashion … I will bequeath you my notes on life in the recruits’ camp of the RAF. They will disappoint you.’ 27Garnett was alarmed and wrote to Bernard Shaw, who sent on the letter to the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, with his card, suggesting that Lawrence’s suicide would create a scandal, especially since Lowell Thomas’s book With Lawrence in Arabiahad just appeared to popular acclaim. He was supported by John Buchan, whom Lawrence had once buttonholed in the street and asked for help. Baldwin intervened personally, and in early July Trenchard sent for Lawrence and informed him that he was to be transferred back to the RAF.

Lawrence felt that he now had all that he had ever wanted. He knuckled down to becoming ‘Ordinary’ and stuck it out more or less faithfully for the next ten years. He was posted to the RAF Cadet College at Cranwell in Lincolnshire – one of the most comfortable postings available – and continued to work on Seven Pillarsand Revolt in the Desertand continuously revised his notes on the life of a recruit in the RAF which would eventually be published as The Mint.In 1926, he was transferred to Karachi in India at his own request, to avoid the publicity which would accompany the appearance of Revolt in the Desertand the subscribers’ edition of Seven Pillars.Although the books were a financial success, Lawrence had by now decided that he should not profit from the Arab Revolt, and donated the money to the RAF Memorial Fund. In November 1927 he was posted to a small hill station at Miranshah, near the border with Afghanistan. Unfortunately, however, there was a rebellion in Afghanistan during 1927-8, and a British newspaper, the Empire News,implicated him, stating that he was operating as British pro-consul in Afghanistan disguised as a holy man. The article was reprinted in India, and led to disturbances in which a genuine holy man was beaten almost to death under suspicion of being Lawrence. The situation had become embarrassing for the British government, and on 8 January 1929 he was flown back to Karachi and a few days later put aboard the S.S. Rajputana,bound for Plymouth. Lawrence’s homecoming from India was a matter of public knowledge: he was hounded by reporters from the moment he arrived back in Britain, and the fact that ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ was serving in the RAF remained well known for the rest of his service. Lawrence was aware that any further sensations in the press would be likely to scupper his career in the ranks for ever, and for a time made an attempt to lie low. Like many public personalities of the twentieth century, he detested the press only when he could not control it – as a gifted propagandist he had been aware of its power from an early age, and in 1911 had been quite happy to use The Timesto manipulate public opinion, and incidentally to get himself a good job. In the immediate post-war period he had fought an energetic campaign in the newspapers to gain support for his views on the Middle East question. Following the dйbвcle in India, though, he began to see it as the double-edged blade it really was.

Lawrence’s last six years in the RAF were in many ways the most contented period of his life. He was now middle-aged, and had grown thick-set: there was no longer any trace of ‘girlishness’ about him. He continued to veer between elation and depression, continued to commute between the barrack-room and his rich, powerful and famous friends, continued to seek anonymity and yet make certain he was clearly seen hiding. In his more balanced moods, he felt that he had come to terms with the world: ‘I measure myself against the fellows I meet and work with,’ he wrote, ‘and find myself ordinary company, but bright and sensible. Almost, I would say, popular!’ 28He had, at least in part, found a sense of community, a sense of belonging among ‘ordinary mortals’. He no longer felt out of his depth with other men. He told an American correspondent that there were no real heroes in the world, and that instead of distinctions between human beings, he was coming to see only similarities. The man who had always been ashamed of his appearance now admitted that the difference between a ‘very big man’ and a ‘very small man’ was only a matter of a few inches, and this difference only appeared important to human beings.

He was posted first to RAF Gattewater on Plymouth Sound, where he developed a genuine friendship with his commanding officer, Wing Commander Sydney Smith, and his wife Clare. Later, after witnessing the crash of an Iris flying-boat in which nine air-crew were killed, he threw himself enthusiastically into a programme of improving fast rescue-boats. He found that he had a special talent for mechanics, which was complemented by his passion for speed – a passion pursued avidly at sea in his private motor-launch Biscuit,and on land on his 1000cc Brough Superior motorcycle, Boanerges. Over the years, Lawrence got through seven Brough motorcycles, which were among the most powerful machines of their day. Speed became one of the few luxuries he indulged in to excess, and only at speed did he seem to recapture that intense feeling of connection with the cosmos which he had felt during the war: ‘When I open out … at 80 or so,’ he told Robert Graves, ‘I feel the earth moulding herself under me … Almost the earth comes alive, heaving and tossing on each side like a sea … It is the reward of speed … I could write you pages and pages on the lustfulness of moving swiftly.’ 29At speed, the body – the part of himself which he had always despised and tried to subdue – was transcended: ‘In speed we hurl ourselves beyond the body,’ he wrote, in one of his few attempts at verse. ‘Our bodies cannot scale the heavens except in a fume of petrol … Bones. Blood. Flesh. All pressed inward together.’ 30

He continued to meet Bruce on occasions, and entertained former colleagues from the RAF and the Tank Corps for musical weekends at Clouds Hill. He wrote scores of letters to artists, writers, composers and former colleagues. He made new friends among the powerful, including the local MP for Plymouth, Nancy Astor, and the Labour MP for Shoreditch, Ernest Thurtle. He became a sort of surrogate son to Bernard Shaw and kept up a lively literary dialogue in hundreds of letters to his wife Charlotte. He undertook reviews and introductions. He started work on a translation of the Odysseyfrom ancient Greek for an American publisher, insisted on publishing it anonymously in Britain, revealed to the literary establishment that he was working on it, and threatened to stop work when the fact was inevitably leaked to the press. Although he occasionally had ideas for books, there was nothing new after The Mint,which Trenchard felt was damaging to the RAF and had asked him not to publish until after his death. He authorized two biographies of himself, by Robert Graves and Basil Liddell Hart, vetted virtually every word, asked both to publish notes declaring he had had nothing to do with the books, and then complained to acquaintances that the authors had availed themselves of too much ‘artistic licence’. He criticized Hart, his sincere admirer, in particular, for having succumbed to his charm and failed to take an objective view, and disdained his biography as ‘Panegyric III’. He also began to realize that while he had thought of himself as a writer, he actually lacked the creative urge: he had all the tricks of writing, he knew, but he had nothing further to say. Occasionally this knowledge led him to fits of melancholy and despair: ‘Life isn’t very gay, I fancy,’ he wrote, ‘and I shouldn’t like to feel that I’d brought anyone into the world to have such times as I’ve had and still have … I have found nothing to justify my staying on, and yet one can’t go – it’s a sad state.’ 31The RAF station had now become his world and at times his prison: he felt afraid and hesitant when outside it. He told a new friend, writer Henry Williamson, that he felt like a clock whose spring had run down. He knew, ultimately, that he was a misfit who had found his proper niche only in the extraordinary circumstances of the Arab Revolt. He had been the perfect man in the right place at the right time, had won the war in the desert, had restored a kind of freedom to the Arabs after 500 years, had written a wonderful book about that experience which nobody would ever forget, and had become the most famous man of his era. He was a phenomenon, but unlike the artists, writers and poets he envied so much, his was a one-time accomplishment which could never be repeated or improved: ‘You have a lifetime of achievement,’ he wrote to Sir Edward Elgar, sadly, in 1932, ‘but I was a flash in the pan.’ 32

Lawrence left the RAF on 25 February 1935, and drove his Brough from his last posting at Bridlington in Lincolnshire to Clouds Hill: ‘My losing the RAF numbs me,’ he wrote, ‘so I haven’t much feeling to spare for a while. In fact I find myself wishing all the time that my own curtain would fall. It seems as if I had finished now.’ 33However, the press had got wind of his retirement and hounded him for the next month, making his life a misery until he came to an arrangement with various newspaper proprietors, and the reporters began to drift away. By April he was alone, and he began to settle in and plan a motorcycle journey around Britain for the summer. He considered writing a biography of the Irish patriot Sir Roger Casement, and began inviting friends to the cottage. Nancy Astor wrote to him, hinting that there might be a possibility of government work – even reorganizing British defence forces. He wrote back that wild horses would not drag him away from Clouds Hill: his will was gone, he told her: ‘there is something broken in the works.’ 34

On 11 May 1935, Lawrence kick-started his motorcycle, Boanerges, and set off to Bovington village, about a mile and a half from Clouds Hill, to send a parcel of books and to dispatch a telegram to Henry Williamson inviting him to lunch the following Tuesday. This was to be Lawrence of Arabia’s last ride. At about 11.20 he drove back to his cottage. The road between Bovington and Clouds Hill was straight, but marked by a series of three dips, and concealed behind one of them were two boy cyclists, Frank Fletcher and Bertie Hargreaves, who were pedalling in the same direction. Lawrence changed down twice to take the dips, and Pat Knowles, his friend and neighbour, who was working in his garden opposite Clouds Hill, heard the crisp changes of gear. Precisely what happened in the next moments is, like so much of Lawrence’s life, a mystery. The boys claimed to have heard the motorcycle coming and moved into single file. Corporal Ernest Catchpole, of the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, who was walking his dog in the waste land to the west of the road, later told the inquest that Lawrence passed a black car coming in the opposite direction, though the boys stated there was no car, and no such vehicle was ever traced. It seems unlikely that Lawrence was travelling at more than forty miles an hour, for Knowles heard the gear changes clearly, and the motorcycle was later found to be stuck in second gear, in which its top speed was thirty-eight miles an hour. Whether his concentration momentarily deserted him, or whether the boys were actually riding abreast, will never be known for certain: what seems to have happened is that Lawrence clipped Bertie Hargreaves’s back wheel, knocking the boy off his bicycle, and swerving to avoid further damage was thrown over the handlebars of his motorcycle and pitched head first on to the road five yards away. The motorcycle twisted and turned and finally lay still. It was over in seconds. Lawrence lay in the road quivering, with his head a mass of blood. Shortly, Corporal Catchpole ran up and tried to wipe away the blood with a handkerchief. At this moment an army lorry came along, and Catchpole stopped it. Lawrence’s body was placed on a stretcher and taken to Wool Hospital. He had suffered severe brain damage, and never recovered consciousness. At last, the rider had hurled himself beyond the body, beyond the point of no return. Six days later, on 19 May, he was dead.