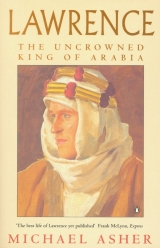

Текст книги "Lawrence: The Uncrowned King of Arabia"

Автор книги: Michael Asher

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 25 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

The railway-wrecking was not finished, however. One armoured car was sent to clear Ramleh, the next station to the south, while Lawrence, in his Rolls-Royce, and other demolition teams blew bridges and miles of track in between. The culverts were demolished by charges stuffed into their drainage-holes, while Lawrence had developed a more effective method of ruining the metals, planting ‘tulip’ charges under the sleepers so that they would buckle and warp entire stretches of track. Having satisfied himself that the railway was now effectively out of service between ash-Shahm and Ramleh, Lawrence slept near ash-Shahm, preparing for the attack on Mudowwara scheduled for the following day. The Turks were expecting the assault, however, and threw the combined force back with deadly accurate artillery fire at 7,000 yards. Lawrence took the armoured cars off in an arc to the place in which he had mined his first train, and destroyed the long culvert about 500 yards from the ridge on which he had sited his Stokes and Lewis guns on that day in 1917. Then he retired back to Ramleh to destroy more line. Later, Mohammad adh-Dhaylan and his Howaytat were sent to cripple the railway north of ash-Shahm. By 20 April, the Arabs and the British together had put out of action eighty miles of track, and taken or cut off seven stations. Fakhri Pasha’s force in Medina had at long last been neutralized as a potential threat.

19. My Dreams Puffed out Like Candles in the Strong Wind of Success

Dara’a, Tafas and the fall of Damascus Winter, 1918

Our battered saloon pulled into Tafas just after noon. It seemed a typical Hauran town – a place without a centre, a sprawl of houses constructed haphazardly along a grid of roads amid acres of wheatlands, and desolate red meadows relieved only by poisonous Sodom apple and brakes of eucalypt, cedar and Aleppo pine. In places you could glimpse the village as it had been in 1918 – scattered among the jerry-built breeze-block dwellings were ancient cottages of black basalt. We trawled up and down the main road for a time, then stopped a swarthy man in a black and white headcloth and asked him if he knew where the battle of 1918 had been fought. ‘I don’t know,’ he said. ‘But there is an old man in the village who was there. I can take you to him.’ I was amazed, and slightly sceptical. All these months I had been pursuing a phantom whom people knew only by hearsay. Was I, finally, to meet someone who had actually seenLawrence with his own eyes? We urged the man into the car, and drove. He stopped us at a modern corner-house set on red earth among Sodom apple bushes. Inside, a spidery old man in a red kuffiyehand a black cloak was sitting on a rug on the floor by a benzene heater, surrounded by half a dozen sons and grandsons. The old man wore thick-rimmed glasses and had a wisp of silver beard. One of his grandsons – a medical student in Aleppo – told me that his grandfather was over ninety years old. We sat down cross-legged on the rug, and after we had answered questions, and sipped the statutory tea, I asked him, with suppressed excitement, if he had ever met Lawrence of Arabia. ‘I saw him,’ the Sheikh told me in a shaky voice. ‘I was just a boy then, of course. I remember seeing the Arab army marching through the village. It was a terrible day. I had been with my parents at another village the night before, and when we arrived here in the morning, we found that the Turks had killed almost everyone. Their bodies were lying about on the road. God have mercy upon them!’

‘And what did Lawrence look like?’

‘A tall, strong man, with a long beard,’ the Arab said.

Later, the grandson took us to see the battlefield, a rolling red meadow, traversed by a stream and full of nests of boulders. It was remarkably close to the village, and seemed unexpectedly small-scale for such a dramatic event. The slaughter of a Turkish column on this very field at Tafas on 27 September 1918, and the subsequent massacre of both Turkish and German prisoners, indeed, were among the most controversial acts of Lawrence’s career – convincing some of his critics that he was a bloodthirsty sadist, or alternatively that his torture and rape at Dara’a had permanently unhinged his passions. It was a controversy that Lawrence stoked with customary glee: ‘The best of you brings me the most Turkish dead,’ he claimed to have told his bodyguard that day, commenting, ‘By my order we took no prisoners, for the first time in the war.’ 1This ruthlessness was engendered by fury at the slaughter of non-combatant peasants in Tafas by the retreating Turks, one of the most sickening sights Lawrence had witnessed in the campaign. Not only had they massacred babies, they had also killed and deliberately mutilated women, leaving their corpses spread out obscenely: Lawrence had seen one pregnant woman lying dead with a bayonet thrust between her legs. Talal, a Sheikh of Tafas, with whom Lawrence claimed to have made his fateful reconnaissance of the Hauran the previous November, he wrote, had been so incensed by the slaughter of his people that he died in a suicidal lone charge towards the massed Turkish ranks.

The Tafas massacre was part of the final phase of the campaign that had begun in May 1918, when Lawrence had applied to Allenby for the 2,000 camels made redundant by the disbanding of the Imperial Camel Brigade in Sinai. ‘And what do you want them for?’ the GOC had asked: ‘To put a thousand men into Dara’a any day you please,’ Lawrence replied. His plan was to mount a force of Arab regulars on camels and march them north from Waheida, the Arabs’ new forward H Q near Ma’an, to Azraq and then to Dara a with a supply column and artillery, machine-guns, armoured cars and aeroplanes. They would carry all their own supplies, reach Dara’a in only a fortnight, and cut the railway with the aid of Bedu irregulars from the Rwalla, just as the GOC made his autumn offensive into Syria. Allenby pondered the request. Camels were scarce in the Middle East, and his Quartermaster required them urgently for another division. Finally, Lawrence’s enthusiasm convinced him. He handed over the camels to the Arab Revolt, and Lawrence rushed to meet Feisal at Aba 1-Lissan the following day, certain that they had just been given the means of final victory. Almost at once, he sent home the Egyptian Transport Corps camel-men who were busily but inefficiently shifting supplies from Aqaba to Aba 1-Lissan, and replaced them with Arab camel-drivers from Mecca, who would put the animals to better use. The organization of logistics was assigned to Captain Hubert Young, the officer Lawrence had first met at Carchemish before the war. Young had been carefully selected by Lawrence himself as an understudy in case he should be killed: he was a fluent Arabic speaker and a first-class organizer, but he was flawed by an irascibility which made it difficult for him to live peacefully with anyone for very long. Nuri as-Sa id wrote that Young’s temper was his own worst enemy, and recalled once managing to soothe some Arab officers whom Young had upset by telling them: ‘Don’t worry. He shouts at the British just the same!’ Had it not been for this Achilles heel, Young might have been another Lawrence of Arabia. Possibly the most able of all the British officers who served with the Arab forces, his powers of visualizing an operation down to the last camel-load far outweighed those of the mercurial Lawrence, who tended to ride first and consider logistics afterwards. Yet while Lawrence charmed, Young had the manner and appearance of a well-intentioned, highly intelligent, but bad-tempered schoolboy. In February 1918 he had been mysteriously ordered from a posting in India to Cairo: ‘It was not until I reported to GHQ at the Savoy …’ he wrote, ‘and the door opened to admit the familiar little figure, that I was enlightened.’ ‘They asked me to suggest someone who could take my place in case anything happened to me,’ said Lawrence, ‘… and I told them no one could. As they pressed me I said I could only think of Gertrude Bell and yourself, and they seemed to think you’d be better for this particular job than she would.’ 2Alan Dawnay, Hedgehog’s CO, soon realized that the ‘understudy’ plan would never work because of Young’s abrasiveness, however, and instead assigned him to the Dara’a operation as Quartermaster.

By 22 July, Young had drawn up a detailed logistics scheme for the mission which was approved both by Joyce, commanding Feisal’s British staff, and by Feisal himself. Lawrence was then in Cairo, making his own plans for the mission with Dawnay, who suggested that they should utilize the last two companies of the Imperial Camel Corps to complete two jobs which the Bedu had as yet failed to carry off: the destruction of Mudowwara, and the demolition of the viaduct at Qissir, north of Ma an. Surprisingly perhaps, Lawrence agreed, and they sent a telegram to Joyce in Aqaba instructing him to establish supply dumps for the ICC force at Rum, Jefer and Bair. These instructions were highly unwelcome in Aqaba: Joyce had not been consulted on the question, and both he and Young saw that every load they had to transport for the Camel Corps operation would mean one load less for their ‘flying column’ to Azraq and Dara’a. Joyce and I discussed this telegram with some grinding of teeth,’ Young wrote, ‘and decided that there was nothing for it but to use some of the priceless camels to put out a dump for [the Mudowwara operation].’ 3On 28 July Lawrence arrived in Aqaba, read Young’s plan and condemned it at once as unworkable. Allenby was intending to make his final push for Damascus on 19 September, and the Arabs were to lead off not more than four days previously. Timing was crucial: ‘[Allenby’s] words to me,’ wrote Lawrence, ‘were that three men and a boy with pistols in front of Dara’a on September 16th … would be better than thousands a week before or a week after.’ 4Young’s plan, he pointed out, would have the Arabs in Dara’a three weeks too late. He unfolded his own scheme, worked out with Dawnay, for a more limited and more mobile operation against Dara’a. Young lost his temper. Lawrence declared sarcastically that he had executed many such mobile operations successfully in the past without the help of a Johnny-come-lately-Old Etonian-regular soldier like Young. Young riposted that Lawrence was proposing this time to move regular soldiers, not Bedu – and regulars were quite another thing. Did he expect them to ride two to a camel and live on a roll of apricot paste and a canteen of water for a fortnight? Where did he think the supplies were coming from? And what about the exfiltration? Lawrence’s plan allowed no provision for a withdrawal, and if the operation failed, they would starve: ‘[Lawrence] never knew very much about the regular army,’ Young wrote; ‘… he had no sympathy for our transport problems, for he held all military organisations in profound contempt and the letter “Q” so justly and deeply revered by regulars had no place in the Lawrentian alphabet.’ 5This was essentially a conflict between the brilliant professional and the brilliant amateur. Joyce had already complained to Dawnay with some justification that Lawrence tended to bombard GHQ, with ambitious and dashing plans but would simply vanish when these ‘wildcat schemes’ had to be put into practice. The meeting ended inconclusively, and the officers scarcely spoke for three days. Young resented Lawrence’s smugness:’… the sight of that little man reading Morte d’Arthurin a corner of the mess tent with an impish smile on his face was not consoling,’ he wrote. 6Finally Joyce capitulated, and accepted Lawrence’s scheme as well as the Camel Corps operation. Young was forced to go along, and employed his genius in ferrying supplies and equipment to Ja’afar Pasha’s regulars at Waheida and Aba 1-Lissan, an operation in which he succeeded against all odds: ‘… to run a harmonious and orderly train was impossible,’ Lawrence grudgingly admitted, ‘but Young very nearly did it, in his curious, ungrateful way. Thanks to him the supply problem of the regulars on the plateau was solved.’ 7

On 4 August, Lawrence guided the Camel Corps companies under Buxton to Rum, and, leaving them to attack Mudowwara without him, flew to Jefer to meet Nuri as-Sha’alan of the Rwalla. He was distinctly apprehensive about this meeting. During his secret northern ride from Nabk in 1917, he had assured the Emir that he could trust the most recent of British promises. Nuri now knew the full terms of the Sykes-Picot agreement, and Lawrence thought he might demand fulfilment of the ‘dishonourable half-bargain’ they had made on that long-ago day in Azraq. What this mysterious ‘half-bargain’ might have been, Lawrence never revealed, only that, on their meeting at Jefer, the Emir did not claim it, and the encounter ended with Nuri giving his whole-hearted support to the Hashemite cause. A few days later, Lawrence returned to Jefer by car with Joyce to meet the Camel Corps, who had successfully captured Mudowwara station and demolished the water-tower. Lawrence completed a reconnaissance mission to Azraq, while the Camel Corps went for the viaduct at Qissir. The mission was abandoned on 20 August when the column was spotted by German aircraft, and Buxton learned that a hostile Bedu tribe lay encamped between them and their target.

Meanwhile, a crisis was shaping up among the regular Arab officers at Aba 1-Lissan, who had read a newspaper report in which King Hussain denied that Ja’afar Pasha had ever been appointed Commander of the Northern Army. This was Hussain’s last attempt to assert control over his son Feisal, who had personally promoted Ja’afar Commander-in-Chief in 1917 without consulting his father. Hussain had always been suspicious of the Arab regular officers, fearing that they would ‘take over’ the Revolt, and it was for this reason he had dismissed Aziz al-Masri, Ja’far’s predecessor, who had, long before Lawrence, developed much of the strategy of the Arab campaign. Hussain knew that Feisal was a weak character, easily swayed by his advisers, and he was terrified that the Arab cause would be hijacked by the Allies’ territorial ambitions. Though Lawrence put Hussain’s reaction down to ‘jealousy’ and ‘lust for power’, the fact is that it suited the British and the French to divide the Hashemites, just as it had suited the Turks. Hussain believed that Feisal was opening the doors for French ambitions in Syria, and while Lawrence later claimed that the old man was ‘crazy’, the Emir was, of course, ultimately proved right.

On reading Hussain’s declaration that there was ‘no Arab officer higher in rank than captain’, Ja’afar Pasha resigned, and was promptly followed by all his staff. Feisal himself resigned in solidarity, which rendered the oaths made to him by the Bedu meaningless. With Feisal’s resignation, the chances of massing the great force of Rwalla Lawrence had counted on for a direct assault on Dara’a dissolved. In one fell swoop, the entire Revolt looked ready to collapse, and on 26 August, Lawrence rushed to Aba 1-Lissan to deal with the impasse. This was a vital moment in the Dara’a operation. That very day, the first of Young’s supply convoys had been about to leave Aqaba, when a cry of ‘Tayaara! Tayaara!’had gone up, and two German aircraft had drummed out of the heat-haze over the Wadi Araba and delivered a package of bombs among the caravans. The animals had gone wild, breaking their lead ropes, bucking and scattering their loads across the plain. With silent curses yet infinite attention to detail, Young had rallied the handlers, picked up the baggage, re-packed the camels, re-strung the caravans, and set the train on its way again. At Aba 1-Lissan, though, the Arab officers would not shift ground without some conciliatory move from Hussain. On 30 August Lawrence telegraphed Clayton that the Hedgehog staff were assuming command of the operation, which would go ahead as planned. Lawrence knew that while they might take Dara’a without Feisal, to have marched into Damascus without him would have meant the defeat of everything they had worked for over the past two years. The Arabs would then be without bargaining power, and the Allies would establish a government in Syria. He told Clayton that he could hold things together for only four days – if no solution were found by then, he would have to evacuate the forward posts and abort the Dara’a mission on which the whole future of the Arabs depended. The days clicked by interminably and there was no word from Hussain. At last, on 4 September, a long message arrived from the King consisting of both a lame apology, and a reiteration of the same accusation in a different form. Lawrence brazenly lopped off the offending part of the message, marked it ‘most urgent’ and sent it to Feisal’s tent.

On 3 September, against all odds, an assault caravan of Arab regulars, together with the French-Algerian artillery battery under Captain Pisani on mules, and a supply column, set out for Azraq. Feisal drove out in his Vauxhall car to review them as the camels strutted out across the grassy downs of the Shirah: ‘As each section saluted Feisal,’ Young wrote, ‘I even felt an absurd lump in my bearded throat at the greatness of the sight.’ 8On the 6th, Lawrence drove to Azraq in a Rolls-Royce tender with Sharif Nasir, who was to lead the Bedu in the final stroke, and Lord Winterton, who had just been transferred to Hedgehog from the disbanded Imperial Camel Corps. Over the next week the assault force began to assemble. On 10 September two aircraft of the recently renamed Royal Air Force landed. Joyce and Stirling – another recent recruit to the Arab mission – came in on 11 September with the armoured cars. Feisal arrived on the 12th with Marshall, the medical officer. Behind him came Nuri as-Said with the 450 Arab regulars, Pisani with his Algerian gunners, the baggage convoy of 1,500 camels with Young, a company of trained demolition-men from the Egyptian Camel Corps under Peake, a section of Gurkha camel-men under Scott-Higgins, and Bedu irregulars of the Rwalla under Nuri ash-Sha’alan, of the Howaytat under Auda and Mohammad adh-Dhaylan, the Bani Sakhr under Fahad, clans of the Seridyyeh and Serahiyyin, Druses, Syrian villagers under Talal al-Haraydhin, Lawrence’s small bodyguard of Hauran peasants and Nasir’s Agayl – a total of almost 1,000 men. As hardware, they had two Bristol aircraft, four quick-firing Napoleon mountain-guns, twenty-four machine-guns, and three armoured cars with their tenders. This was the blade which would carve the victory for which Lawrence had worked so long: the climax of his years of preaching revolt had come. Yet, when the strike force was complete, Lawrence felt despondent. First, he knew that the time of reckoning was near, when the British deception of the Hashemites – and his major role in this charade – would be revealed in all its iniquity. He had raised these ‘tides of men’, he felt, on a sham promise and brought them to worship an ideal of unity in which he could not believe himself. This conflict between the ideal and the prosaic reflected the inner struggle which had been part of Lawrence since childhood. The Arabs themselves were more practical: Auda Abu Tayyi had corresponded with the Turks when the situation had seemed favourable; the Bedu of the Hejaz had retired from the fighting line when it suited them: even Feisal had made overtures to the Turks. Nuri ash-Sha’alan had remained neutral until it seemed that the Hashemites were on the winning side, while many of the tribes, or sections of tribes, of the Hejaz and even of Syria had never joined the Hashemite cause at all. Certainly, Syrian nationalists like Nasib al-Bakri – upon whom Lawrence poured vitriol – were fighting for liberty, but the Hashemites were fighting largely for family patrimony. On their own, they had proved damp squibs: Zayd had lost the Wadi Safra, ‘Ali had almost lost Rabegh. Hussain had sacked his best man, Aziz al-Masri, and almost ruined the final operation by denying that Ja’afar Pasha was his Commander-in-Chief. Zayd had lied to him: Abdallah had rejected his advice. At Azraq he felt a sudden surge of loathing for ‘these petty incarnate Semites’, and for himself who had for two years pretended to be their friend, but had never really become one of them. The terrible fear of being hurt or killed which he had staved off for months, forcing himself to Herculean heights of bravado and self-sacrifice, was reasserting itself with a vengeance. He knew that his nerve was almost at an end, and within a few weeks he must either resign from his position or crack. The old oddness, his sense of inadequacy – absent when he rode with his bodyguard or consorted with Feisal – returned when he found himself among a large crowd. Worst of all, he had heard – perhaps from Syrian recruits – that Dahoum, his pre-war friend, was dead. The boy had been employed as a guard on the Carchemish site until 1916, when almost half the old workforce had perished in a terrible season of sickness and famine. Though Lawrence never mentioned Dahoum by name, he wrote afterwards that one of his main motives in leading the Arabs had been to make a present of freedom to a certain Arab whom he loved. He also wrote that this motive had ceased to exist ‘some weeks’ before the end of the campaign – referring not to the time of Dahoum’s probable death in 1916, but to the moment when he had actually heard of his friend’s demise. Later, composing his dedicatory poem ‘To SA’ while flying between Paris and Lyon in a Handley-Page, he wrote: ‘I wrought for him freedom to lighten his sad eyes: but he had died waiting for me. So I threw my gift away and now not anywhere will I find rest and peace.’ 9In sorrow, anger and apprehension, Lawrence shunned the company at Azraq and walked off alone to ‘Ain al-Assad, where he had, perhaps, spent idle moments in November 1917 with ‘Ali ibn Hussain al-Harithi – another friend he might never see again.

Winterton worried about security: almost as soon as they had arrived at Azraq a Turkish plane had appeared, though it seemed unlikely that they had been spotted. Lawrence knew that the assembly of the raiding force in Azraq could not go unreported to the Turks, but he was confident that the enemy would never venture across the desert to attack them there. Neither could the Turks be sure where they would strike or when it would be. Lawrence had cleverly sent cash to Mithqal of the Bani Sakhr with ‘top secret’ instructions to buy barley for a combined British and Arab surprise attack on as-Salt and Amman on 18 September. He knew that word would instantly be leaked to the Turks, who would spread their defensive resources thinly from Amman to Dara’a. The idea of a direct attack on Dara’a had been abandoned because of the paucity of Rwalla levies, and replaced by a strategy of encirclement in which the strike force would cut the railway to the north, south and west. Without its railway, the Dara’a garrison – only 500 strong – would choke to death. At dawn on 13 September, Peake and Scott-Higgins mounted their camels and led their combined troops of Egyptian sappers and Gurkhas silently through the maze of basalt boulders and across the glistening slicks of the Gian al-Khunna. Two armoured cars rumbled after them in support. Their task was to demolish the tracks and bridges south of Mafraq – a raid which the Turks would probably interpret as a prelude to a strike at Amman. The Gurkhas were to assault the station, while Peake’s sappers cut the railway, and the entire force was to pull out at first light, covered by the armoured cars.

Next day the main body – almost 1,000 strong – set off into the lava, the camels grumbling and stumbling their way through the stones. Nuri as-Sa id rode a horse at the head of the Arab regulars, while Joyce commanded the remaining armoured car and tenders which bounced over the harrabehind. Young, riding a mule, fell into line with Pisani’s mule-mounted gunners, whose Napoleons were stripped and lashed to the broad backs of their mounts. ‘I tried to forget that we were absolutely in the air,’ he wrote, ‘with no communications and no possible way of getting back.’ 10Nuri was more at ease, and recalled that Lawrence’s ‘Plan B’ was to hide out in the lava maze of Jabal Druze for the winter if the mission failed, living off the land. A cavalry screen of Nuri’ash-Sha’alan’s picked riders trotted swiftly about their flanks, and a Bristol fighter flown by Lieutenant Murphy soared out of the clear blue bell of the desert sky, heading for Umm al-Jamal where it later took on a German plane and sent it crashing into the desert in flames. That night they camped amid pickets on the Gian, and the following morning ran into Peake’s assault team, returning disconsolately from Mafraq. The railway strike had failed – indeed, it had not been put in at all. Peake’s force had run into a band of Bedu whom the Turks paid to defend the railway, and while a political officer might easily have managed to turn them, Lawrence had neglected to attach one to the group. Peake and Scott-Higgins had been chary of fighting Arabs, and had turned back. When Lawrence arrived that morning from Azraq in his Rolls-Royce tender ‘Blue Mist’, driven by S. C. Rolls, he was absolutely furious that the job had not been completed, and instead of sending Peake back for a second go, decided to take the armoured cars and do it himself.

On the 15th, Lawrence left the main body at Umm Tayeh – a deserted Roman village with a large water-cistern, which was to be the kicking-off point for the operation – and, with Joyce and Winterton, drove off towards the railway at Mafraq with two tenders and two armoured cars. They raced across the Hauran plain and in the early afternoon sighted their target – a four-arched bridge near a fort at Kilometre 149. The two tenders were left with Joyce beyond a ridge. Winterton’s car drove boldly to the fort and opened up on it with burst upon burst of tracer from its heavy Vickers. The place was defended by a handful of men in an entrenchment, and to the surprise of the British crews they suddenly jumped out of their trenches and advanced towards the car in open order: ‘Not knowing whether they were expected to run away or surrender, 5 as Rolls put it, ‘[they] got up out of their trenches to inquire.’ 11Lawrence surmised later that in fact the cars had appeared so quickly that the Turks believed they belonged to friendly forces. Winterton’s gunner mowed them down mercilessly with another stuttering burst, while Lawrence, in the second car, approached the bridge, his Vickers ripping off a drum at its four guards. Two were killed, and the others surrendered. Lawrence took their rifles and sent them up to Joyce on the ridge. Almost at the same moment the fort surrendered to Winterton: the action had lasted five long minutes.

The peace would not last, though, for Joyce and Rolls, on the ridge, had spotted a Turkish camel-mounted patrol closing on them fast. They drove to Lawrence’s position with more gun-cotton, and helped him set the charges, running back and forth from the cars to the bridge. They set six charges in the drainage-holes of the spandrils, fired them, and withdrew hastily, before the enemy patrol arrived. In seconds there was a terrific blast, which shattered each of the four arches thoroughly. The cars turned towards their base and sped off with the prisoners thrown on the back, but only 300 yards from the railway Blue Mist shuddered to a halt with a broken spring-bracket. The enemy would be on them within ten minutes. The resourceful Rolls leapt out of the driver’s seat and began jacking up the wheel, almost in tears over the potential loss of his beautiful Rolls-Royce. The team was now under fire, and Rolls worked desperately, bathed in sweat. Almost miraculously, he managed to bodge together some lengths of running-board which Lawrence shot off with a pistol and snapped off by hand, and lashed them to the broken spring with telegraph wire. Rolls packed up the jack and tried the suspension cautiously. Incredibly, it held, and as bullets began to ping off the stones around them, Lawrence and Joyce hastily cleared a track, jumped into the car and drove off, jerking and bouncing as fast as Rolls dared, back towards Umm Tayeh. There, they found that Nuri as-Said and the main force had already left for Tel Arar. They stayed at Umm Tayeh for the night to repair the tender as well as they could, and on the 17th, confident that the railway had been cut for a week, they set off to catch up with the assault force.

They overtook the main column at eight o’clock in the morning, just as Nuri was deploying the regulars to assault the redoubt at Tel ‘Arar, five miles north of Dara’a, which was manned by twenty Turks. A squadron of Rwalla horse under Trad ash-Sha’alan dashed magnificently down to the line and hesitated there, thinking it easily taken. Nuri and Young drove down in a Ford tender, and were just enjoying a snort of whisky to celebrate when a Turkish machine-gun crackled up from the redoubt, and an officer in a nightshirt came charging towards them shouting and waving a sabre, like an apparition. For a moment the two officers looked at him, shocked, then, realizing that the garrison at the fort had merely been asleep, Nuri drew his pistol and shot at their assailant, while Young, who was unarmed, rushed to fetch the French artillery. Pisani’s gunners quickly set up their Napoleons and silenced the fort’s defenders with a rapid fusillade of shells. Then the Rwalla horse, with the regulars in support, rushed in and captured it. Nuri, Lawrence and Joyce climbed to the crest of a hill to survey the town of Dara’a and the stations of Mezerib and Ghazala to the north and west of it. The next step was to lay 600 charges on the railway, which Lawrence estimated would completely wreck four miles of track and knock traffic out for a week. After breakfast, the Egyptian sappers and the Algerian gunners began to plaster the tracks with tulip mines. As they deployed along the tracks, Lawrence examined Dara’a aerodrome with his binoculars and was disturbed to see that no less than nine aircraft were being hauled out of their hangars by the German teams. Lawrence’s men had no air cover: Murphy’s Bristol had been badly holed in its clash with a German at Umm al-Jamal, and had retired to Azraq for repair. Lawrence watched Peake’s men labouring on the line below, wondering if they could lay their 600 charges before the planes arrived. Suddenly, the first tulip went up with a noise like a thunderclap and a long plume of black smoke. Almost at once, a Pfalz spotter-plane soared over the hill, sending Lawrence and Nuri scrambling for cover. Moments later two big Albatross bombers and four Haberstadt scouts droned out of Dara’a, circling, diving, strafing them with machine-gun fire, and releasing payloads of bombs, which kicked up V-shaped wedges of debris across the plain. In the Arab ranks there was pandemonium: ‘we scattered in all directions,’ Rolls recalled, ‘I hastily crawled beneath my tender … bombs crashed down, sending up columns of smoke and earth.’ 12Desperately, Nuri placed his Hotchkiss-gunners in cracks on the hillside and soon patterns of tracer were stitching themselves across the sky, forcing the aircraft higher, out of range. Pisani had his Napoleons swivelled up and blatted shells uselessly at the climbing planes. On the railway, the Egyptian sappers went on laying their charges as methodically as ants, and at that moment the second Bristol fighter from Azraq, flown by Lieutenant Junor, cruised defiantly into the midst of the German planes. The Albatrosses and Halberstadts left off their strafing and bombing, and roared off in pursuit. This gave the Arabs a momentary respite, and Lawrence immediately organized a detachment to ride out and cut the Palestine branch of the railway at Mezerib, to complete the isolation of Dara’a. Half an hour later, just as he and his bodyguard were swinging into the saddle, Junor’s Bristol came stuttering back towards them with the Germans buzzing around her like a swarm of bees. Lawrence and Young both realized that she was almost out of fuel. Young yelled to the men to clear a landing-strip. While the others watched impotently, the plane lost height quickly, bounced along the makeshift runway, hit a boulder and pitched heavily over on to her back. Junor leapt out of the crushed cockpit, unhitched his Lewis gun, his Vickers and some drums of tracer, and rushed for the car which Young had considerately driven up to collect him. A second later a Halberstadt came in low and scored a direct hit with a bomb on the wrecked Bristol, which erupted into flames.