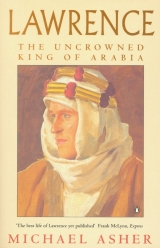

Текст книги "Lawrence: The Uncrowned King of Arabia"

Автор книги: Michael Asher

Жанры:

Биографии и мемуары

,сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 14 (всего у книги 32 страниц)

Lawrence knew that in order to make a proper appreciation he would have to visit Feisal on the Darb Sultani, and the thought did not attract him. He was well aware that the Hejaz was crawling with informers and Turkish sympathizers, and if captured he might be shot as a spy. Moreover, no Christian officers – not even Wilson or Parker – had ever been allowed to visit the front. However, he used all his charm with ‘Abdallah, pretending to support the Sharif’s view that a British landing was necessary, and suggesting obliquely that the decision not to send troops was by no means final. He argued that if he were allowed to speak to Feisal, and see the situation for himself, he might be able to give his backing more convincingly to ‘Abdallah’s case. ‘Abdallah was doubtful. He telephoned Hussain in Mecca to ask his opinion, and the Sharif greeted the proposal with mistrust. This was perhaps the most crucial moment in Lawrence’s entire life. If ‘Abdallah had put the phone down, the story might have ended there and then. Lawrence might have gone back – not unhappily – to his desk in Cairo, and Colonel Lawrence, ‘Lawrence of Arabia’, might never have been born. But for some reason, ‘Abdallah did not put the receiver down. He pushed his father on the point, then handed the phone to Storrs, who supported the idea with all the rhetoric at his command. Reluctantly, against all his principles, the Sharif agreed that Lawrence might ride up the Wadi Safra to visit Feisal. There was to be no turning back: the die had been cast, and the legend-in-the-making had found its path.

In AD 624, the army of the Prophet Mohammad engaged a rival Meccan force at Badr, where the Wadi Safra meets the coastal plain. The Muslims were then but a small sect, and had they lost the battle of Badr, they might well have disappeared. More than 1,000 years later, the Prophet’s direct descendants found themselves in a similar plight. In 1916, Sharif Feisal and his Bedu army were retreating slowly down the Wadi Safra with a Turkish brigade behind them. If the Turks had launched a massive counter-attack at that moment, they would probably have broken through into the coastal plain and taken Rabegh, then Mecca, and the Arab Revolt would have been at an end.

In the Prophet’s day, Badr was an important watering-station on the route to Mecca. Today, though, it is little more than a truck-stop on the motorway, without even a place to stay. I arrived there on a bus from jeddah, late on a steamy night, and stood by the side of the road for an hour desperately trying to flag down a lift. Finally I gave up, bought two small bottles of mineral water, and walked along the soft asphalt for a mile until I found a sandy drywash, where, after carefully avoiding snake and scorpion tracks, I laid out my sleeping-bag. It was too hot to sleep, so I lay watching the stars until morning, and when dawn came, I saw that I was in a wadi forested with patches of thorn-trees and tamarisk, from which granite foothills rose steeply, their sharply carved facets turned at angles to the sun like cut jewels, flashing in the early light. The lower slopes were covered in a down of mustard-yellow goatgrass, which from this distance looked almost like a growth of lichen staining the rock. This yellowish growth solved the riddle of the valley’s name, for Wadi Safra means ‘The Yellow Wadi’ in Arabic. I hiked back to the truck-stop and after half an hour a young Bedui of the Bani Salem Harb agreed to take me to Hamra and Medina in his pick-up for 100 riyals. The Darb Sultani –the road which crawled up the Wadi Safra – opened like a long twisting corridor, climbing up steadily until a vast panorama of mountains lay before us, silver and grey, like successive waves of cloud extending into the distance until they appeared to merge into the sky itself. We passed village after village of ancient baked-mud houses, now standing roofless on the rocky sides of the valley, in forests of date-palms: Jedida, Hussainiyya, Wasta, Kharma. In Lawrence’s day these villages were the heartland of the Bani Salem, and produced almost all the tribe’s grain and dates. The Bedu remained in the villages for five months of the year, spending the rest of the time wandering with their herds and flocks and leaving the villages and palm-groves to their slaves. These slaves, who were mostly of African origin, had no legal status, and numbered about 10,000 at the time of Lawrence’s visit.

My Bedui driver asked what I was about, and when I mentioned ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ he asked, ‘Who?’

‘An Englishman who helped lead the Arab armies in the Great Arab Revolt.’

‘What?’

‘When the Hashemites were here.’

‘Oh, the Hashemites! That was long ago. This is the country of the Saudis now!’

Was he being deliberately obtuse, I wondered, or could tribal memories really have become so short? His people, the Bani Salem, were one of the main clans of the Harb – a major Bedu tribe in the Hejaz. This youth’s grandfathers and grand-uncles had actually fought with Feisal, while many of the Masruh Harb – their rivals – had sided with the Turks, under the ‘traitor’ Sheikh ibn Mubeiriq. It was only after a while that I remembered that it had been the Bani Salem who had run from the Turks at the crucial moment. Perhaps, after all, it was a memory the tribe would rather forget.

Hamra took me by surprise. I had imagined some tiny hamlet in a cleft in the wadi side, but the scale of the place was enormous, with thousands of palms whose heads moved slowly like sea-grass to the tune of the wind. The wadi was about half a mile wide here, lying between two steep, stony walls, and the ruined houses stood on a long ridge at the foot of the northern spur, and on high earth mounds rising steeply from the wadi bed. Lawrence had numbered the houses at about 150, but there were obviously many hundreds more, and there was also the remains of a Turkish fort, a shapeless mud stump on an island in the sea of palms. This village had for generations been a station on the Pilgrim Road from Yanbu’ al-Bahr to Medina, and when Richard Burton had halted here, disguised as a Persian doctor, in 1852, the fort had been manned by a platoon of Albanian soldiers. I climbed the ridge and scrambled among the warren of ruptured and leaning mud walls, eroded into surreal sculptures by the rain, and tried to picture what this village must have been like in late October 1916, when the wadi was full of Feisal’s defeated troops, and three camel-riders, one of them an Englishman, had suddenly appeared on the outskirts of the village.

*

Lawrence and his two rafiqs had left Rabegh on 21 October, under the cover of darkness. From a distance, all three might have been mistaken for Bedu, since Lawrence wore an Arab headcloth and had thrown a cloak over his uniform. Close up, though, he would easily have been recognized as a foreigner. Not only was he cleanshaven and pink-faced, he obviously knew nothing about camel-riding. When he had travelled with camels in the Negev two years previously, he had preferred to walk. Sharif ‘Ali, the eldest of the Hashemite sons, had reluctantly provided him with his best camel and an escort of two Bani Salem – Sheikh Obeyd and his son ‘Abdallah – to take him to Feisal’s camp. Though Lawrence was to masquerade as a Syrian, ‘Ali had ordered Obeyd not to let him talk to anyone: the desert and the hills were full of Turkish spies, and the ‘traitor’ ibn Mubeiriq, whose tribal district they were passing through, would happily have killed Lawrence or sold him to the Turks. The riders cleared Rabegh’s palm-groves and stalked out into the endless coastal plain of the Tihama. There was no moon, and the night yawned infinitely before them, its silence broken only by the soft percussion of the camels’ feet on the flat sand. As the darkness closed in, Lawrence felt suddenly apprehensive. He had entered a hostile and unknown dimension, into which few Europeans had been before him, and from which even fewer had returned alive. He was unsure, even, that he could trust his companions. He knew, of course, that the role of companion or rafiq was a solemn office to the Bedu: every traveller who wanted to cross a tribal district must have a rafiq from the local tribe or one allied to it to frank him through. For a rafiq to turn on his charge once accepted was a heinous affront to the Bedu code of honour, and a Bedui found guilty by his fellow-tribesmen of the crime of bowqa – treachery – would be ostracized for life, and never allowed to marry from his own folk. To be tribeless in a tribal society amounted virtually to a death sentence, for any marauder might kill the outcast without the risk of starting a blood-feud – the one social institution in Arabia which prevented bloodshed on a large scale. Nevertheless, Lawrence reminded himself, like the English code of the ‘gentleman’, the rules the Bedu lived by were only an ideal. The German explorer Charles Huber, for instance, who had come this way in 1884, had been murdered by his Harb rafiqs near Rabegh, when the Arabs had discovered that he was a Christian.

They slept for a few hours that night, wrapped in their cloaks, and were up in the chill of dawn, reaching the well at Masturah in the mellow flush of early light. Some Bedu of the Masruh Harb were crouching under an awning of palm-fronds, and their eyes followed Lawrence’s party suspiciously as they passed. They dismounted by a ruined wall, and Lawrence sat down in the shade. Obeyd and his son took the camels off to water them at a stone shaft, twenty feet deep, with footholds built into its side. While Obeyd held the camels, ‘Abdallah tucked up his dishdashainto his cartridge-belt and slung a goatskin over his shoulder, then descended into the well, feeling for the footholds deftly with his bare feet. He filled the goatskin, shinned up again as surely as a lizard and poured the water into a stone basin. When the animals had drunk their fill, Obeyd carried over a bowl of water for Lawrence to drink. Finally, the two Bani Salem drank themselves. Then they sat down with Lawrence in the shade, to watch the Masruh watering a herd of thin she-camels. ‘Abdallah rolled himself a cigarette.

It was at this moment that Lawrence had a vision. As they watched, he wrote, two young riders came trotting in on richly caparisoned thoroughbred camels, and couched them by the well. One of them, dressed in a fine cashmere robe, tossed his headrope carelessly to the other and ordered him to water them. The young lord strutted arrogantly over to where Lawrence and his rafiqswere sitting, and sank down on his haunches next to them. He was a slim man, little more than a boy, with a slightly pugnacious, inquisitive face, his long hair dressed in plaits, Bedu style. He was powerful-looking and appeared supremely confident. He offered Lawrence a cigarette, freshly rolled and licked, and then inquired if he was from Syria. Lawrence left the question hanging in the air, and asked if the youth was from Mecca. His companion, meanwhile, was making little progress in watering his camels. The Masruh herd was pressing lustily around the stone basin, and the herdsmen had not given the youth a chance to water his beasts as the customary etiquette to travellers demanded. ‘What is it, Mustafa?’ the lord shouted. ‘Water them at once!’ ‘Mustafa’ approached him shamefacedly, and began to explain that the herdsmen would not let him, whereupon the other jumped up with an oath and beat him savagely three or four times about the shoulders with his camel-stick. ‘Mustafa’ looked resentful, but stayed silent. The Masruh, watching from the well, were embarrassed that their own lack of hospitality had caused the boy’s humiliation, and not only gave the young man a place at the water immediately, but offered his camels some fresh shoots to eat. After the animals had eaten and drunk, the young lord climbed upon his camel without couching her, simply pulling her head down gently and stepping on her neck. ‘God requite you!’ he told the Masruh, and rode off with his companion to the south.

No sooner had they gone than Obeyd started to chuckle. Later, after Lawrence and his rafiqshad mounted their camels and were riding north, he explained that the young ‘lord’ was Sharif ‘Ali ibn Hussain of the Harith, and ‘Mustafa’ actually his cousin, Sharif Muhsin. Sharif ‘Ali was a trusted lieutenant of Feisal’s, and despite his age had an outstanding reputation for courage. He had been one of Feisal’s picked bodyguard in Damascus, and had fought next to him on the bloody plains outside Medina at the beginning of June. Later, he had led the raids against the Turkish advance at Bir Darwish. The Harith and the Masruh were blood-enemies, and if the herdsmen at the well had suspected their identities, they might have been driven away. They had invented the charade of master and servant, Obeyd said, to deceive them. Lawrence was entranced by Sharif ‘Ali. For the rest of his time in Arabia, he would be captivated by the image of the ‘noble’ boy-warrior he had glimpsed at Masturah, on his first journey into the desert.

Like several of the questionable incidents in Lawrence’s story, the meeting with Sharif ‘Ali makes no appearance in any official report – though Lawrence often gives details of a far more minor nature. In Seven Pillars, 7this vision sets the scene for the world of deception, conflict and cruelty in which he now found himself: a world of handsome young men who resort frequently to the stick, a world in which the tribes are ancient blood-enemies that only an idea of great influence can unite. Since Obeyd knew the identities of the two Harith Sharifs, though, it seems unlikely that the Masruh at the well would not have recognized them. The Bedu were extremely observant, not missing a single detail – tribesmen who could remember the track of every camel they had ever seen, who could distinguish families and clans simply by the difference in the way they tied their headcloths, are unlikely to have been deceived by the rather amateurish performance, and it would have been obvious from ‘Mustafa’s’ appearance, bearing, clothing, saddlery, and a thousand other tiny details, that he was no servant or slave. Secondly, the story has a ring of familiarity common to many tales in Seven Pillars:the boyish pranks of the young Sharifs are a preview of the ‘naughtiness’ later practised by Lawrence’s servants ‘Farraj and Da’ud’, and the masochistic element – the ‘submission’, ‘humiliation’ and beating of one of the boys – is clear. Such flagellation and public humiliation also play a large role in the ‘Farraj and Da’ud’ story. Sharif ‘Ali emerges from Seven Pillarsas Lawrence’s beau ideal of the desert Arab – the aristocratic Bedui, counterpart of his pre-war love, Dahoum. It seems at least possible, though, that this vision of male beauty Lawrence claimed to have experienced at Masturah was no more than an interior one, since Sharif ‘Ali makes his first appearance in Lawrence’s field diary on 8 March 1917 – five months later – and in this hand-written entry Lawrence describes the Sharif as if seeing him for the first time.

From Masturah, they passed out of the territory of the Masruh and into that of the Bani Salem, to which Lawrence’s rafiqsbelonged. Obeyd showed Lawrence the stone which marked the frontier of his own tribal district. What struck Lawrence most forcibly was the thought that, though Europeans saw the desert as a barren wilderness, to the Bedu it was home. Every tree, rock, hill, well and spring had its owner, and while it was Bedu custom to allow a traveller to cut firewood and to draw water enough for their own use, woe betide any foreign spirit who tried to exploit it. By noon, Lawrence was beginning to feel the strain of the journey. His legs and back were raw and aching from the constant jolting of the camel, his skin blistered from the sun and his eyes painful from peering all morning into the glare of the burning flint. He had been two years in the city, commuting from hotel to office, he realized, and now had suddenly been dumped in the desert without the slightest preparation. As the sun dipped and melted into the west, they arrived at a village of grass huts called Bir ash-Sheikh, belonging to the Bani Salem. The Bedu couched their camels by one of the huts, and were greeted by a woman who showed them a place to sit, and kindled a fire for them outside. Obeyd went off and begged some flour, which he mixed with a little water in a bowl, and kneaded into a flat oval patty. He buried it carefully in the sand under the embers of the fire, waiting twenty minutes, then brushed them away, delved in the sand, and brought out a piping hot, hard-baked loaf. He clapped it with his hand to remove the last grains of sand and broke it into pieces, which the three of them shared. Although Lawrence later claimed that the Arabs thought it ‘effeminate’ to take provisions for a journey of less than 100 miles, this was untrue. The fact was that no Bedui would bother to take food while travelling in his own tribal district, since he could always be certain of obtaining nourishment from his fellow tribesmen on the way. The libbeh –unleavened bread baked in the sand – was the Bedu’s standard fare, and would soon become nauseatingly familiar to Lawrence. For now, though, he ate a little with the best grace he could muster. Afterwards, Obeyd invited him to look at some nearby wells, but he was so stiff after the ride that he declined.

There was a further stretch that night, and at dawn they reached Bir ibn Hassani, the village of Ahmad al-Mansur, one of the great sheikhs of the Harb. As they passed, a camel-rider came loping out of the village and tagged along with them, asking a string of questions, to which Obeyd and his son made short, unwilling, answers. The Arab, whose name was Khallaf, insisted on them eating with him, and forced them to couch their camels. He brought an iron pot out of his saddle-bag, full of baked bread, crumbled and sprinkled with sugar and butter, and offered it to them. Once they had eaten, he told Lawrence that Feisal had been pushed back the previous day from Bir Abbas to Hamra, a little way ahead of them, and he listed the names and injuries of each tribesman who had been hurt. He tried to engage Lawrence in conversation, inquiring if he knew any of the English in Egypt. Lawrence replied in the Aleppo dialect, and Khallaf began asking him about Syrians he knew, then shifted to politics and asked what he thought Feisal’s plans were. Obeyd cut in abruptly and changed the subject, and shortly the man left them. They discovered subsequently that he had been a spy in Turkish pay.

By noon they had come to Wasta, a large village of the Bani Salem, consisting of 1,000 mud houses set on earth mounds and long rocky ridges across the wadi-bed, and above the thick palm groves. Lawrence learned that many of the houses were empty. This year a flood like a tidal wave had broken through the embankment, destroyed many of the palmeries and leached away the carefully preserved topsoil. To cap it all, there had been a terrible plague of locusts which had reduced the harvest still further, driving many of the inhabitants away. They rested in Wasta until early afternoon, then rode up the wadi. Almost at once they began to pass squadrons of Bedu crouching around cooking fires or sitting, smoking in the shade of the trees, and there were caravans laden with provisions on the move. These were Feisal’s men – many of them Bani Salem – who called out greetings to Obeyd as Lawrence’s party passed. Shortly, they saw the village of Hamra before them. They crossed a small stream, and were led up a walled pathway, couching their camels in front of one of the houses. A slave with a scimitar led Lawrence inside, to a smoky room where Feisal was holding court with his military aide,an Iraqi cavalry officer named Maulud al-Mukhlis, and Sheikhs of several Bedu tribes, including the Faqir, the Billi, and the Rwalla – a tribe based in Syria. According to Lawrence, Feisal was already standing at the door when he approached, ‘waiting for him nervously’ – but this is not the Arab way. It is far more likely that when Lawrence entered, the Sharif and his company merely rose to their feet in customary fashion – this was the manner in which they greeted kings and tribesmen alike – while Lawrence shook hands with each of them in turn. He was impressed by the Sharif’s stately appearance, which, he said, reminded him of the monument to Richard the Lionheart – the hero of his youth – at Fontevraud in France. He found Feisal more regal and imposing than his brothers, and this was important: Lawrence’s first reaction to the Arabs had always been aesthetic and the propagandist in him knew that, to appeal to the British, the Arab Revolt should have a leader who at least lookedlike the European idea of the ‘noble Arab’. While ‘Abdallah was too round and jolly, and ‘Ali too sickly and effete, Feisal fitted the bill admirably. For all his noble appearance, though, Lawrence also thought the Sharif looked dog-tired, much older than his thirty-one years, with bloodshot eyes and hollow cheeks, his skin shrivelled with lines of pain. He smoked incessantly. Lawrence claimed in Seven Pillarsthat he had known instinctively that this was ‘the man who would bring the Arab revolt to full glory’, 8yet he told Liddell Hart that in reality he had simply thought that Feisal could be ‘made into a hero of revolt’ more easily than his elder brothers. According to Lawrence, they sat down together among the Bedu, and Feisal asked him: ‘How do you like our place here in the Wadi Safra?’

Lawrence answered: ‘Well; but it is far from Damascus.’

‘The word had fallen like a sword in their midst,’ he wrote. ‘There was a quiver. Then everybody present stiffened where they sat, and held his breath for a silent minute …’It was Feisal, he said, who eased the tension. The Sharif lifted his eyes, smiling, at Lawrence, and said, ‘Praise be to Allah. There are Turks nearer to us than that!’ 9

On the first night, Lawrence and Feisal sat in the smoky room and argued for hours, while the fire crackled and burned down, the dring-drang of the coffee mortar rang out, the coffee and tea went its rounds again and again, and Feisal stubbed out butt after butt. Lawrence found the Sharif most unreasonable. Feisal was indignant that few of the arms he had requested from Wilson had turned up, especially the artillery, and Lawrence became the target of his indignation. Lack of artillery, Feisal maintained, was the Arabs’ main problem: with two field-guns he could have captured Medina. The Bedu were terrified of the very sound of shells, and the merest hint of a barrage sent them scampering for cover like rats. This was not because they were cowards, the Sharif explained – for the Bedu would face bullets and swords steadfastly – but because they could not endure the thought of being blown to bits. Feisal talked about artillery endlessly, and Lawrence perceived that the power of the guns, and the carnage at Medina, had made an ineradicable impression on him. He saw that Feisal’s nerve had been shattered by what he had seen on that day: ‘At [the] original attack on Medina,’ he told Liddell Hart, ‘he had nerved himself to put on a bold front, and the effort had shaken him so that he never courted danger in battle again.’ 10His spirit had been restored by the arrival of the Egyptian battery, but broken again when he saw that the mountain-guns were helpless against the Turkish heavy field-pieces – a shell from the Turkish guns had actually struck his own tent. Privately, Lawrence viewed his regard for artillery as ‘silly’, and felt that, guns or no guns, he had never been near capturing Medina. He also felt that the Sharif had not grasped how to use the Egyptian mountain-guns, whose main advantage was their mobility. He tried to persuade Feisal that irregular soldiers should never try to fight pitched battles, anyway, but should attack in small, self-contained mobile groups. The Turks were dogged defensive fighters, as the British defeat at Gallipoli had demonstrated to their bitter cost, and Lawrence reckoned that a single company of Turks, well-entrenched, could defeat the entire Hashemite army. But the Turks’ strength lay in concentration of numbers, while the strength of the Arabs lay in diffusion: the Bedu, in their tribal wars and forays, had always fought in this way. Feisal disagreed. For weeks now small parties of Bedu had been making lightning strikes on Turkish positions, trying to slow down their advance, and these flea-bites had failed to hold the Turks back: what the Arabs needed was artillery. The Sharif planned to make a massive assault on two of the stations of the Hejaz railway, Buwat and Hafira, just north of Medina, with a 3,000-strong force of Juhayna now stationed at Khayf Hussain. The Turks had concentrated at Bir Darwish, with no less than five battalions of infantry, two Mule Mounted companies, a camel-mounted mountain-gun battery, field-gun batteries, three aircraft and a regiment of ‘Agayl camel-corps. A diversion to the north, Feisal thought, might cause them to retire. Lawrence disliked the plan. He thought that, even with the support of ‘Abdallah to the east, and with Zayd’s force replacing him in the wadi, the Turkish force would only be drawn off by a third, and the remainder might seize the opportunity to push through the Wadi Safra to Rabegh.

Lawrence had been quartered with the Egyptian artillerymen, whose commander, Zaki Bey, had a tent pitched for him. He retired unsatisfied, however. At first light, Feisal and Maulud al-Mukhlis came to see him again, and they argued solidly for five and a half hours. Lawrence had slept well, and, rested after his journey, he made full use of his powers of persuasion. Today, he gradually began to feel that his arguments were telling. Privately, he perceived that Feisal, though highly intelligent, was by nature cautious, and a weaker character than his brother ‘Abdallah, of whom he was notoriously jealous. The Sharif told Lawrence later that when he had advised his father to delay his declaration of the revolt, ‘Abdallah had called him a coward: he referred to his elder brother as mufsid:‘the malicious one’. Feisal was susceptible to advice, whereas ‘Abdallah was not; in fact, Lawrence told Liddell Hart, ‘his defect was that he always listened to his momentary adviser, despite his own better judgement.’ 11This was a very different picture, of course, from the one Lawrence presented in his official dispatches, where he emphasized the fact that Feisal was regarded as a hero by his men, and had risked his life at Medina to hearten his troops. He represented him as impatient and impetuous, hot-tempered and proud, ‘full of dreams and the capacity to realise them’. 12It was not, Lawrence said, the fact that Feisal had been unnerved by a shell through his tent which had caused him to order his troops back from Bir Abbas, but because he was ‘bored with his obvious impotence’ – a languid emotion which smacks more of the Oxford common room than the heat of battle. In reality, he thought Feisal timid and terrified of danger, and this private view was echoed by others who knew Feisal well, such as Pierce Joyce, who wrote that Feisal was ‘not a very strong character and much swayed by his surroundings’. 13Lawrence felt that Feisal’s passion for Arab freedom had forced him to face risks he hated, and since his own masochistic nature obliged him to do the same, he had great empathy with the Sharif. For the British establishment, though, the leader of the Arab Revolt must appear heroic, and Lawrence resolved to ‘make the best of him’, even if this meant portraying his character falsely in his dispatches. 14He was no novice in manipulating the facts and the media to get his way, and he was as passionate about the Arab Revolt as Feisal was: ‘I had been a mover in its beginning,’ he wrote, ‘my hopes lay in it.’ 15This was not pure altruism. Lawrence had been romantically attached to the Arabs since his experiences at Carchemish. He saw Feisal and the revolt as an expression of his own rebellion – the same emotions which had led him to bring Dahoum and Hammoudi to Oxford – the competitive spirit, the ‘beast’ within, which craved others’ notice, yearned for recognition that he was ‘different’ and ‘distinct’. His attitude to the Hashemites was an extension of his attitude to Dahoum, for just as he had written that he wished to help the boy help himself, so he would tell Graves that his object with the Arabs was ‘to make them stand on their own feet’. 16Lawrence felt he knew what was best for Dahoum, and now he knew what was best for the Hashemites. The problem of the Arab Revolt was lack of leadership, he concluded, and he, Lawrence, would provide that leadership through his proxy, the malleable Feisal. For his part, Feisal was moved by Lawrence’s masterly rhetoric, and encouraged that British GHQ were taking a closer interest in his affairs. He had the impression that Lawrence was empowered to make definite promises. Above all, Lawrence’s mysteriousness and whimsicality began to win the Sharif over. At the end of their second discussion, they parted amicably for lunch.

In the afternoon, Lawrence made it his business to stroll around the wadi, chatting with Feisal’s troops. He felt that they were in fine fettle for a defeated army. The Bedu, who had made camp in the palm-groves, mostly belonged to the Juhayna, a large tribe based in the Wadi Yanbu’ to the north, and to the Harb, their deadly enemies. Lawrence saw that Feisal had done a remarkable job in reconciling the traditional foes to fight side by side for the Hashemite cause. He was under no illusion though: it was Hashemite money – ultimately from British coffers – which had bought the Bedu’s allegiance, and if things went badly, they might easily desert to the enemy. The British conception of the tribal levies as a feudal army under the noble Sharifs was quite wrong. In feudal Europe serfs had been the chattels of their lords and bound to military service when required. Not so the Bedu. They were not bound to anyone or anything but their own tribe, and for this reason would not consider it bowqa –treachery – to change sides, as long as such a defection were agreed by the tribe or the family as a whole. The people they served – Hashemites or Turks – were aliens. The Turks already had Bedu irregulars working for them. The Billi, a powerful and xenophobic tribe to the north, were still wavering, and one of their Sheikhs, Suleyman Rifada, had already declared for the Turks. If the Billi went over to the Turks en bloc,then the Juhayna might follow. Nevertheless, Lawrence reckoned that the Turks were spending Ј70,000 a month on attempts to buy the tribes, and were receiving mostly empty promises in return. He believed that ultimately the Hashemites had a sentimental appeal to the Bedu which the Turks could not equal.