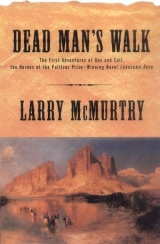

Текст книги "Dead Man's Walk"

Автор книги: Larry McMurtry

Жанр:

Вестерны

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 24 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Captain Salazar looked up, waiting for the Major’s point. He did not have to wait very long.

“They are prisoners,” the Major said. “Prisoners should be tied. Then they should be put up against a wall and shot. That is what we would do with such men in France, if we caught them.”

The Major looked at the dark men who trotted beside the horses. He said something to themone of the dark men immediately went to the pack mule and came back with a handful of rawhide thongs.

“Tie him first,” the Major said, pointing at Bigfoot. “Then tie the one who turned over the General’s buggy. Which is he?”

Salazar gestured toward Call. In a moment, two of the dark men were beside him with the thongs.

Bigfoot had already held out his hands so that the men could tie them, but Call had not. He tensed, ready to fight the dark men, but before his rage broke Bigfoot and Salazar both spoke to him.

“Let it be, Woodrow,” Bigfoot said. “The Major here’s ready to shoot you, and it’s too nice a morning to get shot.”

“He is right,” Salazar said.

Call mastered himself with difficulty. He held out his hands, and one of the dark men bound him tightly at the wrists with the rawhide thongs. In a few minutes, all the Texans were similarly bound.“Perhaps you should chain them, too,” Salazar said, with a touch of sarcasm. “As you know, Texans are very wild.”

Major Laroche ignored the remark.

“Where is the rest of your troop, Captain?” he asked.

“Dead,” Salazar said. “The Apaches followed us into the Jornada del Muerto. They killed some. A bear killed two. Six starved to death.”

“But you had horses, when you left Santa Fe,” the Major said. “Where are your horses?”

“Some are dead and some were stolen,” Salazar admitted. He spoke in a dull tone, not looking at the Major, who sat ramrod stiff on his horse.

When all the prisoners were bound, the Major turned his horse. He looked down once more at Captain Salazar.

“I suggest you go home, Captain,” he said. “Your commanding officer will want to know why you lost half your men and all your horses. I am told that you were well provisioned. No one should have starved.”

“Gomez killed General Dimasio, Major,” Salazar said. “He killed Colonel Cobb, the man who led these Texans. He is the reason I lost the men and the horses.”

Major Laroche curled the ends of his mustache once more.

“No officer in the Mexican army should be beaten by a savage,” he said. “One day perhaps they will let me go after this Gomez. When I catch him I will put a hook through his neck and hang him in the plaza in Santa Fe.”

“You won’t catch him,” Call said.

Major Laroche looked briefly at Call.

“Is there a blacksmith in this village?” he asked.

No one spoke. The men of the village had all lowered their eyes.

“Very well,” the Major said. “If there were a blacksmith I would chain this man now. But we cannot wait. I assure you when we reach Las Cruces I will see that you are fitted with some very proper irons.”

Salazar had not moved.

“Major, I have no horses,” he said. “Am I to walk to Santa Fe? I am a captain in the army.”

“A disgraced captain,” Major Laroche said. “You walked here. Walk back.”

“Alone?” Salazar asked.

“No, you can take your soldiers,” Major Laroche said. “I don’t want themthey stink. If I were you I would take them to the river and bathe them before you leave.”

“We have little ammunition,” Salazar said. “If we leave here without horses or bullets, Gomez will kill us all.”

The priest had come out of the little church. He stood with his hands folded into his habit, watching.

“Ask that priest to say a prayer for you,” Major Laroche said. “If he is a good priest his prayers might be better than bullets or horses.”

“Perhaps, but I would rather have bullets and horses,” Salazar said.

Major Laroche didn’t answer. He had already turned his horse.

The Texans were placed in the center of the column of cavalry the cavalrymen behind them drew their sabres and held them ready, across their saddles. Captain Salazar and his ragged troop stood in the street and watched the party depart.

“Good-bye, Captainif I was you I’d travel at night,” Bigfoot said. “If you stick to the river and travel at night you might make it.”

The Texans looked once more at the Captain who had captured them, and the few men they had traveled so far with. There was no time for farewells. The cavalrymen with drawn sabres pressed close behind them.

Matilda Roberts had not been tied. She passed close to Captain Salazar as she walked out of the village of Las Palomas.

“Adios, Captain,” she said. “You ain’t a bad fellow. I hope you get home alive.”

Salazar nodded, but didn’t answer. He and his men stood watching as the Texans were marched south, out of the village of Las Palomas.

MAJOR LAROCHE MADE NO allowance for weariness. By noon, the Texans were having a hard time keeping up with the pace he set. The pause for rest was only ten minutes; the meal just a handful of corn. The mule that the villagers had so carefully provisioned had become the property of the Major’s cavalry. The Texans hardly had time to sit, before the march was resumed. While they ate their hard corn, they watched the Mexican cavalrymen eat the cheese the women of Las Palomas had provided for them.

Gus was puzzled by the fact that a Frenchman was leading a company of Mexican cavalry.

“Why would a Frenchie fight with the Mexicans?” he asked. “I know there’s lots of Frenchies down in New Orleans, but I never knew they went as far as Mexico.”

“Money, I expect,” Bigfoot said. “I never made much money fightingI’ve mostly done it for the sport, but plenty do it for the pay.““I wouldn’t,” Call said. “I’d take the pay, but I’ve got other reasons for fighting.”

“What other reasons?” Gus asked.

Call didn’t answer. He had not meant to provoke a question from his companion, and was sorry he had spoken at all.

“Can’t you hear? I asked you what other reasons?” Gus said.

“Woodrow don’t know why he likes to fight,” Matilda said. “He don’t know why he turned that buggy over and got himself whipped raw. My Shad didn’t know why he wanderedhe was just a wandering man. Woodrow, he’s a fighter.”

“It’s all right to fight,” Bigfoot said. “But there’s a time to fight, and a time to let be. Right now we’re hog-tied, and we ain’t got no guns. This ain’t the time to fight.”

They marched all afternoon and deep into the night, which was cold. Call kept up, though his foot was throbbing again. Major Laroche sent the dark men ahead to scout. He himself never looked back at the prisoners. From time to time they could see him raise his hand, to curl his mustache.

In the morning, there was thin ice on the little puddles by the river. The men were given coffee; while they were drinking it Major Laroche lined his men up at rigid attention, and rode down their ranks, inspecting them. Now and then, he pointed at something that displeased hima girth strap not correctly secured, or a uniform not fully buttoned, or a sabre sheath not shined. The men who had been careless were made to fall out immediately; the Major watched while they corrected the problem.

When he was finished with his own troops, the Major rode over and inspected the Texans. They knew they were ragged and filthy, but when the Frenchman looked down at them with pitiless eyes they felt even dirtier and more ragged. The Major saw Long Bill Coleman scratching himselfmost of the men had long been troubled by lice.

“Gentlemen, you need a bath,” he said. “We have a fine ceremony planned for you, in El Paso. We will be there in four days. I am going to untie you now, so that you can bathe. We have a fine river herewhy waste it? Perhaps if you bathe in it every day until we reach our destination, you will be presentable when we hold the ceremony.”

“What kind of ceremony would that be, Major?” Bigfoot asked.

“I will let that be a surprise,” Major Laroche said, not smiling.

Gus had taken a strong dislike to Major Laroche’s manner of speakinghis talk was too crisp, to Gus’s ear. He didn’t see why a Frenchman, or anyone, needed to be that sharp in speech. Talk that was slower and not so crisp would be a lot easier to tolerate, particularly on a cold morning when he had enough to do just keeping warm.

“I’m going to release you now, for your bath,” the Major said. “I want you to take off those filthy clotheswe’re going to burn them.”

“Burn ‘em?” Bigfoot said. “Major, we’ve got no other clothes to put on. I admit these are dirty and smelly, but if you burn them we won’t have a rag to put on.”

“You have blankets,” the Major pointed out. “You can wrap those around you, today. Tomorrow we will reach Las Cruceswhen we get there we will dress you properly, so that you won’t disgrace yourselves when we hold the ceremony.”

He nodded to the dark men, who began to cut the rawhide thongs that bound the Texans.

With the cavalry behind them, the Texans were marched to the Rio Grande. They were all apprehensivenone of them trusted the French Major. Besides that, they were cold, and the green river looked colder. The frost had not yet melted from the thorn bushes.

“Strip, gentlemenyour bath awaits,” Major Laroche said.

The Texans hesitatedno one wanted to start undressing. But Major Laroche was looking at them impatiently, and the cavalry was lined up behind him.

“I guess you boys think you’re gents,” Matilda said. “I’m tired of stinking, so I’ll be first, if nobody cares.”

There was a titter from the cavalry, when Matilda began to shed her clothes, but Major Laroche whirled on his men angrily and the titter died. Then he turned back, and watched Matilda walk into the water.

“Hurry, gentlemen,” the Major said. “The lady has set you an example. Hurrywe have a march to make.”

Reluctantly, the Texans began to strip, while the Mexican cavalry watched Matilda Roberts splash in the Rio Grande.“I reckon it won’t hurt us to get clean’ Bigfoot said. “I’d prefer a big brass tub, but I guess this old river will do.”

He undressed; so, finally, did the rest of the men. They were encouraged slightly by the fact that Matilda, skinnier than she had been when she lifted the snapping turtle out of the Rio Grande, but still a large woman, splashed herself over and over, rubbing her arms and breasts with sand scooped from the shallows where she stood.

“It might hurt us if we freeze,” Gus said.

“Oh, now, it’s just water,” Long Bill said. “If it ain’t froze Matty, I guess I can tolerate it.”

The water, when Call stepped in, was so cold he felt as if he had been burned. It sent a pain so deep into his sore foot that he thought for a moment the foot might have died. Gradually, though, wading up to his knees, he came to tolerate the water a little better, and began to follow Matilda’s example, scooping sand from the shallow riverbed and rubbing himself. He was surprised at how white the bodies of the men weretheir faces were dark from the sun, but their bodies were white as fish bellies.

While the Texans splashed, Major Laroche decided to drill his troops a little. He put them through a sabre drill, and then had them present muskets and advance as if into battle.

Wesley Buttons, the youngest and most excitable of the three Buttons brothers, happened to glance ashore just as the cavalry was advancing with their muskets ready. Seeing the advancing Mexicans convinced Wesley that massacre was imminent. They had been expecting death for weeksfrom Indians, from bears, from Mexicans, from the weatherand now here it came.

“Run, boys, they mean to shoot us all!” he yelled, grabbing his two brothers, Jackie and Charlie, by the arms.

Within a second, panic spread among the Texans, though Bigfoot Wallace at once saw that the Mexicans were merely drilling. He yelled out as loudly as he could, but his cry was losthalf the Texans were already splashing deeper into the river, desperate suddenly to get across.

The Mexican cavalry, and even Major Laroche, were startled by the sudden panic which had seized the naked men. For a moment the Major hesitated, and in that moment Bigfoot ran toward the shore, meaning to run to where the Major sat on his horse and explain that the men had merely taken a fright.

Call, Gus, and Matilda were downriver slightly, near the bank where the Mexicans were assembled. Gus had cut his foot on a mussel shell. Call and Matilda were helping him out of the water when the panic started. Long Bill Coleman had already had enough of the freezing water. He had walked back toward the pile of clothes, hoping to find a clean shirt or pants leg to dry himself with.

“Boys, come backcome back!” Bigfoot yelled, turning to look as he splashed ashore; but only the five or six men nearest him understood the command. One of the dark men had been attempting to burn the Texans’ clotheshe was holding a stick of firewood to a shirt, hoping the filthy garment would ignite.

At that moment Major Laroche saw Bigfoot coming, and realized the Texans were merely scared.

He motioned his cavalry forward, disgusted at the delay this foolish act of ignorance would cause himthen, a second later, the cavalry, primed to shoot, and excited by the fact that half the prisoners seemed to be escaping, rushed past the Major before he could stop them, firing at the fleeing men.

“No! no! you stupids! Don’t kill themdon’t kill them!” he yelled.

But his words were lost in the rush of hooves, and the blast of muskets. He sat, helpless and in a cold fury, as his men spurred their horses into the river, some trying to reload their muskets, others slashing at the fleeing Texans with their sabres.

Bigfoot, Call, Matilda, Gus, Long Bill and a few others struggled back to where the Major sat, hoping he could call off his troops. The dark men at once covered them with their guns. None of them Texans, the Major, the dark mencould do anything but watch. Both Bigfoot and the Major were yelling, trying to call off the cavalry before all the fleeing Texans were shot or cut down.

Bigfoot, holding up his hands to show that he meant no harm, walked as close to Major Laroche as the dark men would let him get.

“Major, ain’t there no way to stop this?” he asked. “Don’t you have a bugler, at least?”

Major Laroche had taken out a spyglass, and put it to his eye. Some of the naked men had made it across the narrow river, but many of the cavalrymen had crossed it, too, and were pursuing the running Texans through the cactus and scrub, slashing and shooting.

Major Laroche lowered the spyglass, and shook his head.

“I have no bugler, Monsieur,” he said. “I had one, but he became familiar with the alcalde’s wife, and the alcalde shot him. It was a great annoyance, of course.”

When Gus looked back toward the river, all he could see were horses splashing and men trying to wade or swim, trying to escape the Mexican cavalry anyway they could. But there was no way. As he watched, Jackie Buttons tried to dive under the belly of a horse but the river was too shallow. Jackie came up, his face covered with mud, only to have a cavalryman shoot him down at point-blank range.

“Oh God, they’re killing the boysthey’re killing them all!” Matilda yelled.

Quartermaster Brognoli stood beside her, uncomprehending, his head jerking slightly, as it had jerked the whole of the long trek from the Palo Duro. Sometimes Matilda led him, but mostly Brognoli walked alonenow, naked, he watched the destruction of the troop without seeming to understand it.

Call watched too, silent. The men had been fools to run, when the cavalry had only been practicing; but it was a folly that could not be corrected now. Charlie Buttons crawled out on the opposite shore, and was at once hacked down by two soldiers. He fell back in the river and the river carried him downstream, spilling blood into the water like a speared fish.

“Major, can’t you stop them?” Bigfoot yelled again. “There won’t be a man of them left.”

“I am afraid you are right,” Major Laroche said. “It will mean a much smaller ceremony, when we reach El Paso. I expect the alcalde will be disappointed, and General Medino too.”

“Ceremony! ceremony! Those men weren’t nothing but scared,” Bigfoot said. There were floating bodies and swirls of blood all over the surface of the green water. John Green, a short Ranger from Missouri, managed to wrest a sabre from one of the cavalrymen, but when he tried to stab the soldier he missed, and stabbed the horse in the belly. The horse reared and fell, smashing John Green-and the soldier he had tried to stab; the horse continued to flounder, but neither John nor the soldier rose again.

“Monsieur, I have no bugler, as I said,” Major Laroche remarked, watching them coolly. “My men are soldiers and they smell blood. It would take a cannon shot to stop them now, and I was not provided with a cannon.”

Across the river, Call and Gus could see men running. Some of them had managed to get a hundred yards or more from the river, but there were several cavalrymen for every Texan and none escaped. Guns fired, and sabres flashed in the bright sunlight. The few Texans on the east bank of the river watched the final stages of the massacre silently. Gus felt weak in the stomachCall felt numb. Matilda Roberts had gone blank. She stared across the river, but her gaze was fixed on nothing. Long Bill Coleman stopped looking. He sat down and heaped sand on his naked legs, as a child might. Major Laroche smoked.

Finally, when all the Texans were dead, the Mexican troops began to return. Some had gone almost a mile west of the river, in their pursuit of the Texans. Some were still in the water, stabbing or shooting at any white body that seemed to have life in it. Major Laroche looked at the sun, and finally rode his horse down to the river. He didn’t yell or gesture; he merely sat there, but one by one, his men noticed him. Slowly, they came to themselves. One or two looked embarrassed. They looked to the east bank, and saw that only a few Texans were left alive. A young soldier had just thrust his sabre into one of the floating bodiesCall knew the man only as Bob. The sabre stuck in Bob’s breastbone, and the young cavalryman was unable to pull it out. He yanked harder and harder, lifting Bob’s body completely out of the water at one point. But the sabre was stuckhe could not pull it free, and he was aware that the Major was watching him critically as he smoked.

“Poor Bob, he’s gone, and that boy can’t get him off his sword,” Bigfoot said. He walked down to the water, and motioned for the soldier to pull the body to shore. Nervously, the young cavalryman did as Bigfoot asked. The body trailed a ribbon of blood, which was quickly carried downstream.

When the soldier drew the body to shore, Bigfoot took it and carried it a few yards up the bank. He motioned for Call and Gus to come help him, and they did. The young Rangers held the cold body of the dead man steadyBigfoot carefully put his foot on the dead man’s chest and, with a great heave, pulled the sabre out.

“Why, that wasn’t near as hard as getting that Comanche lance out of your hip,” Bigfoot observed. He handed the sabre to the young soldier, who took it with a hangdog look.

Major Laroche slowly rode his horse across the river, looking upstream and down, as he counted the corpses. Then he rode up on the west bank and began to bring back his soldiers. As they rode back across the river, they swished their bloody sabres in the water before shoving them back in their scabbards. While they were crossing, the horse with the sabre stuck in its belly floundered out of the river and stumbled past Call and Gus. Call made a lucky grab, and pulled the sabre free. For a moment, looking at the bodies of his friends dead on the far bank or in the river, he felt a rage building. Four Mexican soldiers were in the river, coming right toward him; Call looked at them, the sabre in his hand. The soldiers saw the look and were startled. One of them raised his musket.

“Don’t, Woodrow,” Gus said, as another of the soldiers lifted his gun. “They won’t just whip you this time. They’ll kill you.”

“Not before I kill a few of them,” Call said.

But he knew his friend was right. The Mexican cavalry, led by the stern Major, was coming back across the Rio Grande. He could not fight a whole cavalry without giving up his life. The rage was in him, but he did not want to give up his life. When the Major rode up, Call held the sabre out to him; the Major took it without comment.

Gus was looking across the river. The Mexicans had made no effort to bring back the bodies of the dead Texanssome of those killed in the river had floated downstream, almost out of sight. Jackie Buttons’s body was stuck on a snag, near the far bank. Jackie floated on his back, the green water washing over his face.

“I’ll miss Jackie,” Gus said, to Matilda. “He was slow at cards maybe that’s why I liked him so.”

Matilda was still naked, mud on her legs. “I wish I’d never looked, when the killing started,” she said. “I don’t like to look at killings, not when it’s boys I know.”

“Matty, I don’t either,” Gus said. He was wishing that the body of Jackie Buttons would come loose from its snag and float on down the river. He had often cheated Jackie at cards-not for much cash, but steadily, over the months of their travelsnow, he regretted it. He knew Jackie Buttons was a little slow mindedit would have been better just to deal the cards fairly. Perhaps, now and again, Jackie would have won a hand or two.

But he had not dealt the cards fairly, and in all their playing, Jackie Buttons had not won a single hand. Now he never would, because he was floating on his back in a river, water coursing over his dead eyes and through his open mouth.

“Oh, dern,” he said, and began to cry. He cried so hard he knelt down, covering his face with his arm. He was hoping that when he looked up again the body of the comrade he had cheated would be gone.

Matilda came out of her trance, and put her hand on Gus’s shoulder.

“Are you crying for one of them, or for all of them?” she asked.

“Just for Jackie,” Gus said, when he was calmer. “I cheated him at cards. He wasn’t no cardplayer, but every single time I played him I cheated.”

“Well, Jackie won’t mind now,” Matilda said. “But you ought to stop dealing them cards so sly, Augustus. Someday you’ll meet somebody who’ll be as quick with a gun as you are with an ace.”

“No, I won’t,” Gus said. “I’m always slyer than anybody, when it comes to cards.”

Matilda looked over at Callhe had given up his sabre, but not his rage. He looked as he had looked the day he turned the General’s buggy over, in order to get at Caleb Cobb.

“I’ll be glad to get you boys home,” she said. “Woodrow’s a fighter and you’re a cheat. If I can just get you home, I don’t want to hear of you joining no expeditions.”

Gus sat down by the water’s edgehe suddenly felt very tired.

“All right, Matty,“he said.

“Get up, let’s gothe Major’s waiting,” Matilda said. The Mexican cavalry passed so close that water from the horses’ legs splashed on them.

Gus didn’t think he could get up; his legs had simply given out. But Matilda Roberts offered her strong handGus took it, and got to his feet. Call was still standing as if frozen, looking at the corpses in the river.

“I don’t expect there’ll be no burying,” Bigfoot said, as Gus and Matilda came up.

His guess was rightthere was no burying.

Woodrow Call stood where he was, looking at the blood-streaked river, until the dark men came to tie his wrists and lead him away.

MAJOR LAROCHE WAS A believer in cold-water bathing. He himself bathed every morning at dawn, in the Rio Grande. Three cavalrymen were required to shield him with a ring of sheets, while he sat in the icy river, breathing deeply. When he finished he insisted that each horse be led into the river, where they could be brushed until their coats shone. Often, while the horses were being brushed, the Major would mount and practice with his own fine sabre, slashing at cactus apples while racing at full speed.

The Texans were allowed blankets and a good fire, but they still had no clothes. Though Call despised Major Laroche, he could not help being impressed by the Major’s skill with the sabre. Sometimes he would have his men throw gourds in the air, for him to slash as he raced. His horsemanship was also a thing of skillthe Major could turn his mount in midstride, if one of the gourds was thrown too far to the right or the left. His saddle was polished to a high gleamhe seemed to enjoy this morning practice more than therest of his duties. All day he rode at the head of his column of cavalry, seldom looking back.

Once, as they were nearing Las Cruces, a jackrabbit sped beneath the Major’s horsein a second the Major was after the rabbit. He overtook the jack within fifty yards, and with one stroke severed its head. Then he handed the sabre to his orderly to clean, and resumed his ride at the head of the column.

“I don’t like them dandified little saddles,” Gus remarked.

“Why not?” Call asked. “That Frenchie sits his like he was glued to it.”

“He won’t be glued to it if Buffalo Hump gets after him,” Gus said. He knew that they were close to El Pasobeyond it was the wilderness where Buffalo Hump had killed Josh Corn and Zeke Moody. Lately, the thought of the big Comanche had been often in his mind.

Call didn’t answerhe had not been listening very closely. He thought himself to be an adequate rider, but he knew he could not control a horse as well as the little French Majornor as well as the humpbacked Comanche, who had raced across the desert holding a human body across his horse while he rode bareback. The Frenchman, running at full speed, had sliced the jackrabbit’s head off as neatly as if he were sitting at a table, cutting an onion. The Comanche had scalped Ezekiel Moody, while racing just as fast.

No Ranger that Call had yet seen could ride as well as either the Comanche or the Frenchman. Gus McCrae was a better rider than he was, but Gus would be no match for either the Major or Buffalo Hump, in a fight. Call resolved that if he survived, he would learn as much as he could about correct horsemanship.

“The Major’s better mounted,” Call said. The Major rode a bay thoroughbred, deep chested and fast.

“Buffalo Hump would get him with that lance,” Gus said. “He nearly got me with that lance, remember?”

“I didn’t say he couldn’t,” Call said.

But the next day, he watched the Major as he put his horse through his morning paces. Gus was annoyed that Call would bother watching such a man exercise his horse.

“I don’t like the way he curls his damn mustache,” Gus said. “If I had a mustache I’d just let it grow wild.”

“Let it grow anyway you want,” Call said. “I got no opinion.“At the village of Mesilla, just south of Las Cruces, the surviving Texansthere were only ten, not counting Matilda_were finally given clothes: shirts that fell to their knees, and pants that were baggy and rough.

Then, as Major Laroche watched, an old blacksmith put the ten Texans in leg irons. The leg irons were heavier than the ones they had worn in Anton Chico, and the chains were too short for any of the men to take a full stride.

“Major, I could crawl to El Paso faster than I can walk in these dern ankle bracelets,” Bigfoot said.

“You won’t have to walk, Monsieur,” the Major said. “We have a fine wagon for you to ride in. We want you to be rested for our little ceremony.”

The fine wagon turned out to be an oxcart, drawn by an old black ox. The ten men fit in the wagon, but Matilda didn’t. Gus offered to give her his place, but Matilda shook her head.

“I’ve walked this far,” she said. “I reckon I can walk on into town.”

Ahead, northeast of the river, they could see a grey mountain looming. Although the men were chained, and the oxcart bumped along at a slow pace, the cavalrymen kept pace around it with their sabres drawn. After two hours of bumping along, Gus’s bladder began to trouble himbut when he started to slide out of the wagon to take a piss, the soldiers leveled their sabres at him.

“All right then, if that’s the rule, I’ll just piss over the side,” Gus said, standing up. “I don’t want to wet my new pants.”

He stood up and peed off the end of the oxcart, watched by the soldiers with the sabres. In time, several of the Texans did the same.

It was dusk when the cart bumped into the outskirts of El Paso. A strong wind was blowing, whirling dust into their faces. They could not see the mountain ahead or the river to the west. As night came, the wind rose higher and the dust obscured everything. Now and then, they passed little hutsdogs barked, and a few people came out to look at the soldiers. Matilda kept her hand on the side of the oxcart; the dust was blowing so thickly that she was afraid she might lose her way and be without her companions.

In the cart, the men hid their heads and waited for the journey to be over. Now and then, Call looked out for a minute. He saw a few more buildings.“I guess they call it the Pass of the North because all this dern wind out of New Mexico blows through it,” Bigfoot said. “If it gets much stronger, it’ll be blowing pigs at us.”

As he said it, they heard over the keening wind a faint sound that they could not identify.

“What’s that?” Bigfoot asked.

Call, whose hearing was as keen as Gus McCrae’s sight, was the first to identify the sound.

“It’s a bugle,” he said. “I guess they’re sending the army now.”

Ahead, through the dust, they saw what seemed to be moving lights; soon a line of infantrymen with lanterns, led by a captain and a bugler, met the cavalrymen. The bugler continued to blow his horn, although the wind snatched the sound away almost before the notes were sounded. The soldiers with the lanterns formed a line beside the oxcart as it bumped along toward the town. One soldier, startled by the sudden appearance of a large woman at his side, dropped his lantern, which smashed on a rock. The infantry captain yelled at the soldier; then he in turn was startled as Matilda Roberts appeared, almost at his elbow. Then they heard shouts and the sound of snarling dogsthere was a shot, and several of the cavalrymen galloped ahead. The snarling got louder, there were more shots, and then a squeal from one of the dogs. A minute later Major Laroche, his sabre drawn, rode close to the oxcart and peered in at the Texans.