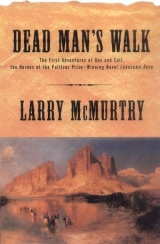

Текст книги "Dead Man's Walk"

Автор книги: Larry McMurtry

Жанр:

Вестерны

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

“Hi, Pa, this is Mr. Augustus McCrae of Tennessee,” Clara said merrily. “He’s a Texas Ranger but he seems to have time to spare, so I put him right to work.”

“I see,” Mr. Forsythe said. He shook Gus’s hand and looked at Clara, his daughter, with great fondness.

“She’s brash, ain’t she?” he said to Gus. “You don’t need to wait for an opinion, if Clara’s around. She’ll get you an opinion before you can catch your breath.“Clara was still unpacking goods, whistling as she worked. She had her sleeves rolled up, exposing her pretty wrists.

“Well, I must go look at them horses,” Gus said. “Many thanks for the visit.”

“Was it a visit?” Clara said, giving him one of her direct glances.

“Seemed like one,” Gus said. He felt the remark was inadequate, but couldn’t think of another.

“That door ain’t locked. You can come back and pitch in with the unpacking, Mr. McCrae, if you have time,” Clara said.

Old man Forsythe chuckled.

“If he doesn’t have it, he’ll make it,” he said, putting his arm around his daughter’s shoulder for a moment.

Gus tipped his hat to both of them and walked out the front door, the scraps of wrapping paper still in his hand. Once out of Clara’s sight he carefully folded the brown paper and put it in his breast pocket.

Although he had left the general store and was back amid the throng of peddlers and merchants, all hoping to profit from the coming expedition, in his mind Gus still stood by the big box of dry goods, waiting for Clara Forsythe to hand him another swatch of cloth. Call, who was standing with Long Bill and Blackie Slidell not twenty yards away, had to yell at him three times to get his attention.

“Here, I hope you’re pleased with this musket,” Call said, when Gus finally strolled over. “It’s new and it’s got a good heft. I don’t know what we’ll do about pistols. Mr. Brognoli says they’re costly.”

“I don’t want to go,” Gus said flatly. “I wonder if that girl’s pa would hire me to work in that store?”

“What?” Call said, shocked. “You don’t want to go on the expedition?”

“No, I’d rather marry that girl,” Gus said.

Long Bill and Blackie Slidell thought it was the funniest joke of the year. They laughed so hard that the dentist, who was about to pull another tooth out of another customer, stopped his work for a moment in amazement.

Call, however, was embarrassed for his friend. The expedition to Santa Fe was a serious matter. They were Rangersthey had to defend the Republic. Yet Gus had just walked into a store to select a musket, spotted a girl with a frank manner, and now wanted to quit rangering.“Marry heryou ain’t got a cent,” Call said. “Anyway, why would she have you? You ain’t known her ten minutes.”

“Ten minutes is enough,” Gus said. “I want to marry her, and I aim to.”

“He’s a cutter, ain’t he?” Long Bill commented. “Meets a girl and the next thing you know, he’s off to hunt a preacher.”

“Well, you heard me,” Gus said. “I aim to marry her, and that’s that.”

“No, now you can’t, that’s desertion,” Blackie pointed out. “You signed your mark this morning, right in front of Caleb Cobb. I expect he’d hang you on the spot if you tried to quit.”

The remark had a sobering effect. Gus had totally forgotten signing his mark and putting himself under military command. He had forgotten most of his life prior to meeting Clara. The fact that he could be executed for changing his mind had never occurred to him.

“Why, that marking don’t amount to much,” Gus said. He didn’t want to be hanged, but he also didn’t want to leave Austin, now that he had found the woman he intended to marry.

“You need to visit the whorehouse, it will clear your head,” Long Bill said. “My head’s cloudy, too. I say we all go, once we’ve picked our horses.”

“I don’t want no whore,” Call saidbut in fact, once they picked their horses and bought a slicker apiece, they all went down by the river, where several whores were working out of a shanty. There were six stalls, with blankets hung between them. Gus chose a Mexican girl, and did his business quicklyonce he was done, even as he was buckling his pants, he still thought of Clara Forsythe and her pretty wrists.

Call chose a young white woman named Maggie, who took his coins and accepted him in silence. She had grey eyesshe seemed to be sad. The look in her eye, as he was pulling his pants up, made him a little uneasyit was a sorrowful look. He felt he ought to say something, perhaps try to talk to the girl a little, but he didn’t know how to talk to her, or even why he felt he should.

“Thank you, good-bye,” he said, finally.

Maggie didn’t smile. She stood at the back of the stall, by the quilt she slept on and worked on, waiting for the next Ranger to come in.Johnny Carthage was waiting when Call came out. He had a policy of not buying Mexican women, the reason being that a Mexican whore had stabbed out his eye while trying to rob him.

“Well, what’s your opinion? Is she lively?” Johnny asked, as Call came out.

“I have no opinion,” Call said, still troubled by the sorrow in Maggie’s eyes.

Gus McCRAE MOPED ALL afternoon, and would do no work. Call, who had become an expert farrier, took it upon himself to shoe the Rangers’ new horses. He didn’t want one of them coming up lame, not on such a long, risky trip. Shadrach showed up while he was workinghe was dusty and grizzled. When asked where he had been, Shadrach said he had been west, hunting cougars.

“Dern, when I hunt I want something that’s better eating than a cougar,” Bigfoot informed him.

“I just take the liver,” Shadrach said.

“Cougar liver?” Bigfoot asked in amazement. “I’ve heard the Comanches eat the liver out of cougars, but Comanches eat polecats, too. I ain’t yet et a polecat, and I hope I never have to eat the liver out of a mountain cat.”

“It’s medicine,” Shadrach said. “Good medicine. I’m likely to see some cougars, going across the plains.”

“OhI guess you’ve started thinking like an Indian, Shad,” Bigfoot said.

“The better to fight ‘em,” Shadrach said. He went over and dipped his head in a big water trough to get some of the dust out of his long, shaggy hair.

Gus finally agreed to help a little with the horseshoeing, but his mind wasn’t on his work. If Call asked for a rasp, Gus would likely hand him an awl, or even a nail. Twice he wandered off to visit the general store, but Clara was off on errands. Mr. Forsythe was pleasant to him, but vague about when his daughter might return.

“I can’t predict her,” he said. “She’s like the wind. Sometimes she’s quiet, and sometimes she’s not.”

Annoyed at the girlwhy couldn’t she stay where he could find her?Gus took the best alternative left to him, which was to get drunk. He bought a jug of liquor from a Mexican peddler and sat under a shed and drank it, while Call finished the horseshoeing. While he was working, a buggy drove byan old man wearing a military coat was asleep in it. The old man had a red face, and was snoring so loudly they could hear him even after the buggy had passed.

“Well, that’s Phil Lloyd, the damned sot,” Bigfoot said. “He’s a general, but he ain’t a good one. I doubt we could get enough barrels of whiskey in a wagon to keep Phil Lloyd happy all the way to Santa Fe, unless we lope along quick.”

Call decided the military was peculiarwhy make a general out of an old man who couldn’t even find his way around? He tried to interest Gus in the question, but Gus could not be bothered by such business.

“She wasn’t there,” he said several times, referring to Clara. “I went back twice to visitshe said I mightbut she wasn’t there either time.”

“I expect she’ll be there in the morning,” Call said. “You can trot by and say adios. They say we’re leaving tomorrow.”

“You may be leaving, I ain’t,” Gus replied. “I ain’t leaving tomorrow, or any other time.”

Call knew his friend was too drunk to make sensehe didn’t press him.

“Let’s walk down by the river, I feel restless,” Gus said a little later. “That store’s closed by nowthere’s no chance to visit until tomorrow.”

Call was happy to walk with him. It was a starry night, and theRangers had just made a good meal off some tamales Blackie Slidell had purchased from a Mexican woman. A little walk would be pleasant. He took his new musket, in case they encountered trouble. The Comanches had been known to come right into Austin and take children, or even young women. It wouldn’t hurt to be armed.

They walked a good distance on the bluffs over above the Colorado Riverthey could see a light out in the water. Somebody was out in a boat.

“Fishing, I expect,” Call said.

Gus was still fairly drunk.

“What kind of fool would fish at night? The fish wouldn’t be able to see the bait,” Gus said. Then, between one step and the next, he suddenly plunged into space. He was so drunk he wasn’t frightened; sometimes when very drunk he passed outit felt a little like falling. He assumed, for a moment, that he must be in the process of passing out. The lantern light on the water was spinning, which went with being drunk, too.

He felt himself turn over, which was also a feeling he got when he was drunk; then he saw the river again, but it seemed to him that it was above him. He began to realize that he was falling, through a night so dark that he couldn’t see anything. He couldn’t even remember what he had been doing before he fell.

“A fish don’t need to see, it can smell,” Call said, just before noting, to his shock, that he was talking to nobody. Gus McCrae, at his elbow only the moment before, had disappeared. Call’s first thought was that an Indian had snatched Gus, though he didn’t see how, since he and Gus had only been a step apart. But Buffalo Hump had taken Josh Corn, and he hadn’t been far away, either.

Call whirled around, almost going off the bluff himself. He couldn’t see the edge, but he could see the river in the starlight. The river was a good distance downhe realized then that Gus must have fallen. He didn’t know what to doprobably it was too late to do anything. Gus might already be dead or dying. Call knew he had to get down to him, but he didn’t know how to go about it without falling himself. He had no rope, and it was so dark he feared to try and climb down.

Then he remembered that during the day he had seen an old man with a fishing pole making his way down a kind of trail. Therewas a way down, but he would need a light of some kind if he was going to find it.

Call began to run back toward town, staying well clear of the bluff; he was hoping to encounter someone with a light. But it was as if suddenly he were back on the long plain beyond the Pecos: he saw not a soul until he had run all the way back to where the Rangers were camped. When he got there he discovered that the only Ranger who wasn’t dead drunk was gimpy Johnny Carthage, the slowest man in camp. Blackie Slidell and Rip Green were so drunk they couldn’t even remember who Gus McCrae was. Johnny Carthage was willing, at least; he and Call found a lantern, and made their way back to the river. In time, they found a place where they could scramble down the cliff.

The problem then was that Call could not tell how far down the bluff they had walked before Gus fell. With the help of the lantern, though, he could see that the bluff wasn’t high enough for a fall to be fatal, unless Gus had been unlucky and broken his neck or his back.

Johnny Carthage was fairly stalwart while they were on the bluff. But once down by the river, with help far away, his fear of Indians grew to such proportions that he flinched at every shadow.

“Indians can swim,” he announced, looking out at the dark water.

“Who can?” Call asked. He wanted to call out to Gus, but of course if there were Indians near, the calling would give them away. He was afraid Johnny might panic, if the risks increased much.

“Indians,” Johnny said. “That big one with the hump could be right out there in the water.”

“Why would he be out there, this time of night?” Call asked. Mainly he was trying to distract Johnny from his fear by asking sensible questions.

“Well, he might,” Johnny said. He had a great urge to shoot his gun, although he couldn’t see a thing to shoot at. He just had the feeling that if he shot his gun, he might feel a little less scared.

To Call’s shock and surprise, Johnny suddenly shot his gun. Call assumed it meant he had seen Indiansperhaps Buffalo Hump was in the river. Johnny Carthage was ten years older than he was, and more experiencedhe might have spotted an Indian in the water somehow.“Did you hit him?” Call asked.

“Hit who?” Johnny said.

“The Indian you shot at,” Call said.

Johnny was so scared he had already forgotten his own shot. He remembered wanting to shoothe felt it would make him less nervousbut he had no memory of actually firing the gun.

Gus McCrae couldn’t get the stars above him to come into focus. He was lying on his back, a terrible pain in his left ankle, wondering if he was drunk or dead. Surely if he was dead, his ankle wouldn’t hurt so badly. But then, he wasn’t sureperhaps the dead could still feel. He couldn’t be sure of anything, except that his left ankle hurt. He could hear the lap of water against the shore, which probably meant that he was still alive. He wasn’t wet, eitherthat was good. One of the things he disliked most about rangering was that it very often left him unprotected from the elements. On the first march to the Pecos, he had been drenched several timesonce, crossing some insignificant little creek, his boots had filled with water. When he took them off to empty them, he noticed several of the older Rangers laughing, but it wasn’t until he tried to put his boots back on that he realized what they were laughing at. He couldn’t get his boots back onhis feet, which had just come out of those very boots, wouldn’t go back in. They didn’t go back in for almost two days, until the boots had thoroughly dried. Gus remembered the incident mainly because his ankle hurt sohe knew he could never force his foot into a boot, not with his ankle hurting so badly. He would just have to go bootless on that foot for awhile, until his ankle mended.

While he was thinking about the difficulties that arose when you got wet, a gun went off nearby. Gus’s thought was that it was an Indianhe tried to roll under a bush, but there were no bushes on the river shore. Even though he disliked being wet, he didn’t dislike it as much as he disliked the thought of being taken by an Indian. He started to roll into the water, thinking that he could swim out far enough that the Indians couldn’t find him, when he heard nearby the voices of Johnny Carthage and Woodrow Call, talking about the very subject he had just been thinking about: Indians.

“Here, boysit’s me!” he cried out. “Come fastI’m right by the bluff.”

A moment later Call and Johnny found him, to his great relief.“I was afraid it was that big one,” he said, when they came with the lantern. “He could poke that big lance right through me, if he came upon me laying down.”

Though glad to have found Gus alive, Call was still not sure exactly what the situation was. Neither was Johnny. The fact that the latter had fired his gun confused them both. Though not quite dead drunk, Johnny was actually less sober than Call had supposed him to be back at the camp. He had seemed sober in comparison with Blackie and Rip, but now whatever he had drunk seemed to have suddenly caught up with him. He couldn’t remember whether he had fired his gun because he had seen an Indian, or whether he had just shot to be shootingit could even be that the gun had gone off entirely by accident.

Call was exasperated. He had never known a man to be so vague about his own behaviour.

“You shot the gun,” he reminded Johnny, for the third time. “What did you shoot it atan Indian?”

“Matilda et that big turtle,” Johnny saidhe was growing rapidly less in command of his faculties. All he could remember of his earlier life was that Matilda Roberts had cooked a snapping turtle in a Ranger camp on the Rio Grande.

“That wasn’t tonight, Johnny,” Call insisted. “That was a long time back, and I don’t know what it’s got to do with tonight. You didn’t shoot at a snapping turtle, did you?”

Johnny Carthage was silent, perplexed. Call couldn’t help but be annoyed. They were in a life-or-death situationwhy couldn’t the man remember what he shot at?

“What did you shoot at tonight?” he asked again.

Gus was feeling more and more convinced that he was alive and wellexcept, of course, for a damaged ankle.

“I hope my ankle ain’t brokeit hurts,” he said. “You might as well let up on Johnny, though. He ain’t got no idea why he shot his gun.”

“I’d have to be hungry to eat a dern turtle,” Johnny Carthage said. It was his final comment of the evening. To Call’s intense annoyance he lapsed into a stupor, and was soon as prostrate as Gus.

“Now I’ve got two of you down,” Call said. “This is a damn nuisance.“Gus was too relieved to be alive, to worry very much about his friend’s distemper.

“I wonder if that girl will be in the store tomorrow? he asked, out loud. “I sure would like to see that girl again, although my ankle’s bad.” “Go see her, then,” Call said brusquely. “Maybe she’ll sell you a crutch.”

WHEN CALL HELPED Gus hobble back to campJohnny Carthage was no help, having passed out drunk near where Gus had fallen Bigfoot happened to be there, drinking with Long Bill and Rip Green. After a certain amount of poking and prodding, during which Gus let out a yelp or two, Bigfoot pronounced his ankle sprained but not broken. Gus’s mood sankhe was afraid it meant that he would not be allowed to go on the expedition.

“But you wasn’t going anyway, you were aiming to stay and marry that girl,” Call reminded him.

“NoI aim to go,” Gus said. “If I could collect a little of that silver we could live rich, if I do marry her.”

In fact he was torn. He had a powerful desire to marry Clara; but at the same time, the thought of watching his companions ride off on their great adventure made him moody and sad.

“You reckon Colonel Cobb would leave me, because of this ankle?” he asked.

“Why no, there’s plenty of wagons you could ride ina sprain’s usually better in a week,” Bigfoot said. “I guess they could put you in that buggy with old Phil Lloyd, unless they mean to transport him in a cart.” “Ride with a general?” Gus asked. “I wouldn’t know what to say to a general.”

“You won’t have to say a word to Phil Lloyd, he’ll be too drunk to talk,” Bigfoot assured him.

The next morning, the sprained ankle was so swollen Gus couldn’t put even a fraction of his weight on it. The matter chagrined him deeplyhe had hoped to be at the general store at opening time, in order to help Miss Forsythe with her unpacking. Yet even standing up was painfulneedles of pain shot through his ankle.

“I expect they have liniment in that store,” Call told him. “I guess I could walk up there and buy you some liniment.”

“Oh, you would!” Gus said, agitated at the thought that Call would get to see Clara before he did. “I suppose you’ll want to help her unpack dry goods, too.”

“What?” Call said, puzzled by Gus’s annoyance. “Why would I want to help her unpack? I don’t work in that store.” “Bear grease is best for sprains,” Long Bill informed him. “Well, do we have any?” Gus asked, eager to head off Call’s trip to the general store.

“Why noI don’t keep any,” Long Bill said. “Maybe we can scrape a little up, next time we kill a bear.”

“I seen a bear once, eating a horse,” Gus remembered. “I didn’t kill him, though.”

Call grew tired of the aimless conversation and walked on up to the store. The girl was there, quick as ever. She wasn’t unpacking dry goods, though. She was stacking pennies on a counter, whistling while she did it.

“Be quiet, don’t interrupt me,” she said, throwing Call a merry glance. “I’ll have to do this all over if I lose my count.”

Call waited patiently until she had finished tallying up the pennies she wrote the total on a little slip of paper.

“So it’s you and not Mr. McCrae,” she said when she was finished. “I rather expected Mr. McCrae. I guess he ain’t as smitten as I thought.”

“Oh, he’s mighty smitten,” Call assured her. “He meant to be here early, but he fell and hurt his ankle.”

“Just like a manis it broke?” Clara asked. “I expect he done it dancing with a senorita. He looks to me like he’s the kind of Texas Ranger who visits the serioritas.”

“No, he fell off a bluff,” Call said. “I was with him at the time. He’s got a bad sprain and thought some liniment might help.”

“It might if I rubbed it on myself,” Clara said.

Call was plain embarrassed. He had never heard of a woman rubbing liniment on a man’s foot. It seemed improper to him, although he recognized that standards might be different in Austin.

“If I could buy some and take it to him, I expect he could just rub it on himself,” Call said.

“I see you know nothing of medicine, sir,” Clara said, thinking she had never met such a pompous young fool as Mr. Woodrow Call.

“Well, can I buy some?” Call asked. He found it tiring to do so much talking, particularly since the girl’s manner was so brash and her attitude so confusing.

“Yes, herewe have the best liniment of any establishment in town,” Clara said. “My father uses this oneI believe it’s made from roots.”

She handed Call a big jar of liniment, charging him twenty cents. Call was dismayed at the pricehe hadn’t supposed liniment would cost more than a dime.

“Tell Mr. McCrae I consider it very careless of him, to go falling off a bluff without my permission,” Clara said, as she was wrapping the jar of liniment in brown paper. “He might have been useful to me today, if he hadn’t been so careless.”

“He had no notion that he was so close to the edge, Miss,” Call said, thinking that he ought to try and defend his friend.

“No excuses, tell him I’m very put out,” Clara demanded. “Once I smite a man, I expect more cautious behaviour.”

When Call reported the conversation to Gus, Gus blamed it all on him.

“I suppose you informed her that I was drunkyou aim to marry her yourself, I expect,” Gus said, in a temper.

Call was astonished by his friend’s irrationality.

“I don’t even know the woman’s name,” he told his friend.

“Pshaw, it don’t take long to learn a name,” Gus said. “You mean to marry her, don’t you?”

“You must have broke your brain, when you took that fall,” Call said. “I don’t intend to marry nobody. I’m off to Santa Fe.”

“Well, I am tooI wish I’d never let you go up to that store,” Gus said. He was tormented by the thought that Clara Forsythe might have taken a liking to Call. She might have decided she preferred his friend, a thought so tormenting that he got up and tried to hobble to the store. But he could put no weight on the wounded ankle at allit meant hopping on one leg, and he soon realized that he couldn’t hop that far. Even if he had, what would Clara think of a man who came hopping in on one leg?

He was forced to lie in camp all day, sulking, while the other Rangers went about their business. Long Bill Coleman grew careless with the jug of whiskey he had procured the night before. While he was trying to repair a cracked stirrup, Gus crawled over to Bill’s little stack of bedding, uncorked the jug, and drank a good portion of it. Then he crawled back to his own spot, drunk.

Brognoli, the quartermaster, showed up about that time, looking for men to load the ammunition wagons. Call and Rip Green were recruited. Gus was fearful Brognoli would remove him from the troop once he found out about the ankle, but Brognoli scarcely gave him a glance.

“You’ll be running buffalo in a few days, Mr. McCrae,” Brognoli said. “I’ll warn you though: be careful of your parts, once we’re traveling. Colonel Cobb won’t tolerate stragglers. If you can’t make the pull, he’ll leave you, and you’ll have to come back as best you can.

Gus managed to sneak several more pulls on Long Bill’s jug, and was deeply drunk when he woke from a light snooze to see a girl coming toward the camp. To his horror, he realized it was Clara Forsythe. It was a calamitynot only was he drunk and too crippled to attend himself, he was also filthy from having accidentally rolled into a mud puddle during the night.

He looked about to see if there was a wagon he could hide under, but there was no wagon. Johnny Carthage was snoring, his head on his saddle, and no one else was in camp at all.

“There you areI had hoped you would show up early and help me unpack those heavy dry goods,” Clara said. “I see you’re unreliableI might have suspected it.” She was smiling as she chided him, but Gus was so sensitive to the fact that he was drunk and filthy that he hardly knew what to do.

“Let’s see your foot,” Clara said, kneeling down beside him.

Gus was startled. Although Call had informed him that Clara intended to rub liniment on his foot herself, Gus had given the report no credit. It was some lie Call had thought up, to make him feel worse than he felt. No fine girl of the class of Miss Forsythe would be likely to want to rub liniment on his filthy ankle.

“What?” he askedhe was so drunk that he could hardly stammer. He wished now that he had not been such a fool as to drain Long Bill’s jugbut then, how could he possibly have expected a visit from Miss Forsythe? Only whores prowled around in the rough Ranger camps, and Clara was clearly not a whore.

“I said, let’s see your foot,” Clara said. “Did the fall deafen you, too?”

“No, I can hear,” Gus said. “What would you want with my foot?” he asked.

“I need to know if I think you’re going to recover, Mr. McCrae,” Clara said, with a challenging smile. “If you do recover, I might have plans for you, but if you’re a goner, then I won’t waste my time.

“What kind of plans?” Gus asked.

“Well, there’s a lot of unpacking that needs to get done around the store,” Clara said. “You could be my assistant, if you behave.”

Gus surrendered the wounded foot, which was bare, and none too clean. Clara touched it gently, cupping Gus’s heel in one hand.

“The thing is, I’m a Ranger,” Gus reminded her. “I signed up for the expedition to Santa Fe. If I try to back out now, the Colonel might call it desertion and have me hung.”

“Fiddle,” Clara said, feeling the swollen ankle. She lowered his foot to the ground, noticed the jar of liniment sitting on a rock nearby, and removed the top.

“Well, they can hang you for desertion, if they take a notion to,” Gus said.

“I know that, shut up,” Clara said, scooping a bit of liniment into her hand. She began to massage it into the swollen ankle, a dab at a time.“My pa thinks this expedition is all foolery,” Clara went on. “He says you’ll all starve, once you get out on the plains. He says you’ll be back in a month. I guess I can wait a month.”

“I hope so,” Gus said. “I wouldn’t want no one else to get the job.”

Clara looked at him, but said nothing. She continued to dab liniment on his ankle and gently rub it in.

“That liniment stinks,” Gus informed her. “It smells like sheepdip.

“I thought I told you to shut up,” Clara reminded him. “If you weren’t crippled we could have a picnic, couldn’t we?”

Gus decided to ignore the commenthe was crippled, and wasn’t quite sure what a picnic was, anyway. He thought it was something that had to do with churchgoing, but he wasn’t a churchgoer and didn’t want to embarrass himself by revealing his ignorance.

“What if we’re out two months?” he asked. “You wouldn’t give that job to nobody else, would you?”

Clara considered for a momentshe was smiling, but not at him, exactly. She seemed to be smiling mostly to herself.

“Well, there are other applicants,” she admitted.

“Yes, that damn Woodrow Call, I imagine,” Gus said. “I never told him to go up there and buy this liniment. He just did it himself.”

“Oh no, not Corporal Call,” Clara said at once. “I don’t think I fancy Corporal Call as an unpacker. He’s a little too solemn for my taste. I expect he would be too slow to make a fool of himself.”

“That’s right, he ain’t foolish,” Gus said. He thought it was rather a peculiar standard Clara was suggesting, but he was not about to argue with her.

“I like men who are apt to make fools of themselves immediately,” Clara said. “Like yourself, Mr. McCrae. Why, you don’t hesitate a second when it comes to making a fool of yourself.”

Gus decided not to comment. He had never encountered anyone as puzzling as the young woman kneeling in front of him, with his foot almost on her lap. She didn’t seem to give a fig for the fact that his foot was dirty, and he himself none too clean.

“Are you drunk, sir?” she asked bluntly. “I think I smell whiskey on your breath.” ‘“Well, Long Bill had a little whiskey,” Gus admitted. “I took it for medicine.”

Clara didn’t dignify that lie with a look, or a retort.

“What were you thinking of when you walked off that cliff, Mr. McCrae?” Clara asked. “Do you remember?”

In fact, Gus didn’t remember. The main thing he remembered about the whole previous day was standing near Clara in the general store, watching her unpack dry goods. He remembered her graceful wrists, and how dust motes stirred in a shaft of sunlight from the big front window. He remembered thinking that Clara was the most beautiful woman he had ever encountered, and that he wanted to be with herbeyond being with her, he could conceive of no plans; he had no memory of falling off the cliff at all, and no notion of what he and Woodrow Call might have been discussing. He remembered a gunshot and Call and Johnny finding him at the base of the bluff. But what had gone on before, or been said up on the path, he couldn’t recall.

“I guess I was worrying about Indians,” he said, since Clara was still looking at him in a manner that suggested she wanted an answer.

“Shucks, I thought you might have been thinking of me,” Clara said. “I had the notion I’d smitten you, but I guess I was wrong. I haven’t smitten Corporal Call, that’s for sure.”

“He ain’t a corporal, he’s just a Ranger,” Gus said, annoyed that she was still talking about Call. He didn’t trust the man, not where Clara was concerned, at least.