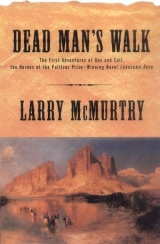

Текст книги "Dead Man's Walk"

Автор книги: Larry McMurtry

Жанр:

Вестерны

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 20 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Shadrach slept cold that nightMatilda stayed with Call, warming him with her body. He went from fever to chill, chill to fever. The old Mexican helped Matilda build a little fire. The old man seemed not to sleep. From time to time in the night, he came to tend the fire. Gus didn’t sleep. He was back and forth all night Matilda got tired of his restless visits.

“You just as well sleep,” she said. “You can’t do nothing for him.”

“Can’t sleep,” Gus said. He couldn’t get the whipping out of his mind. Call’s pants legs were stiff with blood.

When dawn came Call was still alive, though in great pain. Captain Salazar came walking over, and examined the prisoner.

“Remarkable,” he said. “We’ll put him in the wagon. If he lives three days, I think he will survive and walk to the City of Mexico with us.”

“You don’t listen,” Matilda said, the hatred still in her eyes. “I told you yesterday that he’d bury you.“Salazar walked off without replying. Call was lifted into one of the supply wagonsMatilda was allowed to ride with him. The Texans all walked behind the wagon, under heavy guard. Johnny Carthage gave up his blanket, so that Call could be covered from the chill.

At midmorning the troop divided. Most of the cavalry went north, and most of the infantry, too. Twenty-five horsemen and about one hundred infantrymen stayed with the prisoners. Bigfoot watched this development with interest. The odds had dropped, and in their favorthough not enough. Captain Salazar stayed with the prisoners.

“I am to deliver you to El Paso,” he said. “Now we have to cross these mountains.”

All the Texans were suffering from hunger. The food had been scantyjust the same tortillas and weak coffee they had had for supper.

“I thought we were supposed to get fed, if we surrendered,” Bigfoot said, to Salazar.

All day the troop climbed upward, toward a pass in the thin range of mountains. The Texans had been used to walking on a level plain. Walking uphill didn’t suit them. There was much complaining, and much of it directed at Caleb Cobb, who had led them on a hard trip only to deliver them to the enemy in the end. There were Mexicans on every side, thoughall they could do was walk uphill, upward, into the cloud that covered the tops of the mountains.

“The bears live up here,” Bigfoot mentioned, lest anyone be tempted to slip off while they were climbing into the cloud.

When Call first came back to consciousness, he thought he was dead. Matilda had left the wagon to answer a call of naturethey were in the thick of the cloud. All Call could see was white mist. The march had been halted for awhile and the men were silent, resting. Call saw nothing except the white mist, and he heard nothing, either. He could not even see his own handonly the pain of his lacerated back reminded him that he still had a body. If he was dead, as for a moment he assumed, it was vexing to have to feel the pains he would feel if he were alive. If he was in heaven, then it was a disappointment, because the white mist was cold and uncomfortable.

Soon, though, he saw a form in the mista large form. Hethought perhaps it was the bear, though he had not heard that there were bears in heaven; of course, he might not be in heaven. The fact that he felt the pain might mean that he was in hell. He had supposed hell would be hot, but that might just be a mistake the preachers made. Hell might be cold, and it might have bears in it, too.

The large form was not a bear, thoughit was Matilda Roberts. Call’s vision was blurry. At first he could only see Matilda’s face, hovering near him in the mist. It was very confusing; in his hours of fever he had had many visions in which people’s faces floated in and out of his dreams. Gus was in many of his dreams, but so was Buffalo Hump, and Buffalo Hump certainly did not belong in heaven.

“Could you eat?” Matilda asked.

Call knew then that he was alive, and that the pain he felt was not hellfire, but the pain from his whipping. He knew he had been whipped one hundred times, but he could not recall the whipping clearly. He had been too angry to feel the first few licks; then he had become numb and finally unconscious. The pain he felt lying in the wagon, in the cold mist, was far worse than what he had felt while the whipping was going on.

“Could you eat?” Matilda asked again. “Old Francisco gave me a little soup.”

“Not hungry,” Call said. “Where’s Gus?”

“I don’t know, it’s foggy, Woodrow,” Matilda said. “Shad’s coughinghe can’t take much fog.”

“But Gus is alive, ain’t he?” Call asked, for in one of his hallucinations Buffalo Hump had killed Gus and hanged him upside down from a post-oak tree.

“I guess he’s alive, he’s been asking about you every five minutes,” Matilda said. “He’s been worriedwe all have.”

“I don’t remember the whippingI guess I passed out,” Call said.

“Yes, up around sixty licks,” Matilda said. “Salazar thought you’d die, but I knew better.”

“I’ll kill him someday,” Call said. “I despise the man. I’ll kill that mule skinner that whipped me, too.”

“Oh, he left,” Matilda said. “Most of the army went home.”

“Well, if I can find him I’ll kill him,” Call said. “That is, if they don’t execute me while I’m sick.”

“No, we’re to march to El Paso,” Matilda said.

“We didn’t make it when we tried to march to it from the other side,” Call reminded her. Then a kind of red darkness swept over him, and he stopped talking. Again, the wild dreams swirled, dreams of Indians and bears.

When Call awoke the second time, they were farther down the slope. The sun was shining, and Gus was there. But Call was very tired. Opening his eyes and keeping them open seemed like a day’s work. He wanted to talk to Gus, but he was so tired he couldn’t make his lips move.

“Don’t talk, Woodrow,” Gus said. “Just rest. Matilda’s got some soup for you.”

Call took a little soup, but passed out while he was eating. For three days he was in and out of consciousness. Salazar came by regularly, checking to see if he was dead. Each time Matilda insulted him, but Salazar merely smiled.

On the fourth day after the whipping, Salazar insisted that Call walk. They were on the plain west of the mountains, and it had turned bitter cold. Call’s fever was still higheven with Johnny Carthage’s blanket, he was racked with a deep chill. For a whole night he could not keep stillhe rolled one way, and then the other. Matilda’s loyalties were torn. She didn’t want Call to freeze to death, or Shadrach either. The old man’s cough had gone deeper. It seemed to be coming from his bowels. Matilda was afraid, deeply afraid. She thought Shad was going, that any morning she would wake up and see his eyes wide, in the stare of death. Finally she lifted Call out of the wagon and took him to where Shadrach lay. She put herself between the two men and warmed them as best she could. It was a clear night. Their breath made a cloud above them. They had moved into desert country. There was little wood, and what there was the Mexicans used for their own fires. The Texans were forced to sleep cold.

The next morning, finding Call out of the wagon, Salazar decreed that he should walk. Call was semiconscious; he didn’t even hear the command, but Matilda heard it and was outraged.

“This boy can’t walkI carried him out of the wagon and put him here to keep him warm,” she said. “This old man don’t need to be walking, either.”

She gestured at Shadrach, who was coughing.Salazar had come to like Matildashe was the only one of the Texans he did like. But he immediately rejected her plea.

“If we were a hospital we would put the sick men in beds,” he said. “But we are not a hospital. Every man must walk now.”

“Why today?” Matilda asked. “Just let the boy ride one more day with one more day’s rest, he might live.”

“To bury me?” Salazar asked. “Is that why you want him to live?” He was trying to make a small jest.

“I just want him to live,” Matilda said, ignoring the joke. “He’s suffered enough.”

“We have all suffered enough, but we are about to suffer more,” Salazar said. “It is not just you Texans who will suffer, either. For the next five days we will all suffer. Some of us may not live.”

“Why?” Gus asked. He walked up and stood listening to the conversation. “I don’t feel like dying, myself.”

Salazar gestured to the south. They were in a sparse desert as it was. They had seen no animals all the day before, and their water was low.

“There is the Jornada del Muerto,” he said. “The dead man’s walk.”

“What’s he talking about?” Johnny Carthage asked. Seeing that a parley was in progress, several of the Texans had wandered over, including Bigfoot Wallace.

“Oh, so this is where it is,” Bigfoot said. “The dead man’s walk. I’ve heard of it for years.”

“Now you will do more than hear of it, Senor Wallace,” Salazar said. “You will walk it. There is a village we must find, today or tomorrow. Perhaps they will give us some melons and some corn. After that, we will have no food and no water until we have walked the dead man’s walk.”

“How far across?” Long Bill asked. “I’m a slow walker, but if it’s that hard I’ll try not to lag.”

“Two hundred miles,” Salazar said. “Perhaps more. We will have to burn this wagon soonmaybe tonight. There is no wood in the place we are going.”

The voices had filtered through the red darkness in which Call lived. He opened his eyes, and saw all the Texans around him.

“What is it, boys?” he asked. “It’s frosty, ain’t it?”

“Woodrow, they want you to walk,” Gus said. “Do you think you can do it?”

“I’ll walk,” Call said. “I don’t like Mexican wagons anyway.”

“We’ll help you, Corporal,” Bigfoot said. “We can take turns toting you, if we have to.”

“It might warm my feet, to walk a ways,” Call said. “I can’t feel my toes.”

Cold feet was a common complaint among the Texans. At night the men wrapped their feet in anything they could find, but the fact was they couldn’t find much. Few of them slept more than an hour or two. It was better to sit talking over their adventures than to sleep cold. The exception was Bigfoot Wallace, who seemed unaffected by cold. He slept well, cold or hot.

“At least we’ve got the horses,” he remarked. “We can eat the horses, like we done before.”

“I expect the Mexicans will eat the horses,” Gus said. “They ain’t our horses.”

Call found hobbling on his frozen feet very difficult, yet he preferred it to lying in the wagon, where all he had to think about was the fire across his back. He could not keep up, though. Matilda and Gus offered to be his crutches, but even that was difficult. His wounds had scabbed and his muscles were tighthe groaned in deep pain when he tried to lift his arms across Gus’s shoulders.

“It’s no good, I’ll just hobble,” he said. “I expect I’ll get quicker once I warm up.”

Gus was nervous about bearshe kept looking behind the troop. He didn’t see any bears, but he did catch a glimpse of a cougar just a glimpse, as the large brown cat slipped across a small gully.

Just then there was a shout from the column ahead. A cavalryman, one of the advance guard, was racing back toward the troop at top speed, his horse’s hooves kicking up little clouds of dust from the sandy ground.

“Now, what’s his big hurry?” Bigfoot asked. “You reckon he spotted a grizzly?”

“I hope not,” Gus said. “I’m in no mood for bears.”

Matilda and Shadrach were walking with the old Mexican, Francisco. They were well ahead of the other Texans. All the soldiers clustered around the rider, who held something in his hand.“What’s he got there, Matty?” Bigfoot asked, hurrying up. “The General’s hat,” Matilda said.

“That’s mighty odd,” Bigfoot said. “I’ve never knowed a general to lose his hat.”

Two MILES FARTHER ON they discovered that General Dimasio had lost more than his hathe had lost his buggy, his driver, his cavalrymen, and his life. Four of the cavalrymen had been tied and piled in the buggy before the buggy was set on fire. The buggy had been reduced almost to ashthe corpses of the four cavalrymen were badly charred. The other cavalrymen had been mutilated but not scalped. General Dimasio had suffered the worst fate, a fate so terrible that everyone who looked at his corpse bent over and gagged. The General’s chest cavity had been opened and hot coals had been scooped into it. All around lay the garments and effects of the dead men. Both the fine buggy horses had been killed and butchered.

“Whoever done this got off with some tasty horse meat,” Bigfoot said.

Except for the burned cavalrymen, all the dead had several arrows in them.

“No scalps taken,” Bigfoot observed.“Apaches don’t scalpain’t interested,” Shadrach said. “They got better ways to kill you.”

“He is right,” Salazar said. “This is the work of Gomez. For awhile he was in Mexico, but now he is here. He has killed twenty travelers in the last monthnow he has killed a great general.”

“He wasn’t great enough, I guess,” Bigfoot said. “I thought he rode off with a skimpy guardI guess I was right.”

“Only Gomez would treat a general like this,” Salazar said. “Most Apaches would sell a general, if they caught one. But Gomez likes only to kill. He knows no law.”

Bigfoot considered that sloppy thinking.

“Well, he may know plenty of law,” he said. “But it ain’t his law and he don’t mind breaking it.”

Salazar received this comment irritably.

“You will wish he knew more law, if he catches you,” he said. “We are all in danger now.”

“I doubt he’d attack a party this big,” Bigfoot said. “Your general just had eleven men, counting himself.”

Salazar snapped his fingers; he had just noticed something.

“Speaking of counting,” he said. “Where is your Colonel? I don’t see his corpse.”

“By God, I don’t neither,” Bigfoot said. “Where is Caleb?”

“The coward, I expect he escaped,” Call said.

“More than that,” Gus said. “He probably made a deal with Gomez.”

“No,” Salazar said. “Gomez is Apachehe is not like us. He only kills.”

“He might have taken Caleb home with him, to play with,” Long Bill suggested. “I feel sorry for him if that’s so, even though he is a skunk.”

“I doubt Caleb Cobb would be taken alive,” Bigfoot said. “He ain’t the sort that likes to have coals shoveled into his belly.”

Before the burials were finished, one of the infantrymen found Caleb Cobb, naked, blind, and crippled, hobbling through the sandy desert, about a mile from where the Apaches had caught the Mexicans. Caleb’s legs and feet were filled with thornsin his blindness he had wandered into prickly pear and other cactus.

“Oh, boys, you found me,” Caleb said hoarsely, as he was helped into camp. “They blinded me with thorns, the Apache devils.““They hamstrung him, too,” Bigfoot whispered. “I guess they figured he’d starve or freeze.”

“I expect that bear would have got him,” Gus said.

Even Call, beaten nearly to death himself, was moved to pity by the sight of Caleb Cobb, a man he thoroughly despised. To be blind, naked, and crippled in such a thorny wilderness, and in the cold, was a harder fate than even cowards deserved.

“How many were they, Colonel?” Salazar asked.

“Not many,” Caleb said, in his hoarse voice. “Maybe fifteen. But they were quick. They came at us at dawn, when we had the sun in our eyes. One of them clubbed me with a rifle stock before I even knew we were under attack.”

For a moment he lost his voice, and his ability to stand. He sagged in the arms of the two infantrymen who were supporting him. The leg that had been cut was twisted in an odd way.

“Fifteen ain’t many,” Gus said. He didn’t like seeing men who had been tortured, whether they were alive or dead. He couldn’t keep his mind off how it would feel to have the tortures happen to him. The sight of Caleb, with his leg jerking, his eyes ruined, and his body blue with cold, made him want to look away or go away but of course he couldn’t go away without putting himself in peril of the Apaches and the bears.

“Fifteen was enough,” Bigfoot said. “I’ve heard they come at you at dawn.”

Captain Salazar was thinking of the journey they had to make. He kept looking south, toward the dead man’s walk. The quivering, ruined man on the ground before him was a handicap he knew he could not afford.

“Colonel, we have a hard march ahead,” the Captain said. “I’m afraid you are in no condition to make this march. The country ahead is terrible. Even healthy men may not survive it. I am afraid you have no chance.”

“Stick me in a wagon,” Caleb said. “If I can have a blanket, I’ll live.”

“Colonel, we cannot take the wagons across these sands,” Salazar said. “We will have to burn them for firewood, probably tonight. They have blinded you and crippled you.”

“I won’t be left,” Caleb said, interrupting the Captain. “All I need is a good doctorhe can fix this leg.““No, Colonel,” Salazar said. “No one can fix your leg, or your eyes. We can’t take you across the sandswe have to look to ourselves.”

“Then send me back,” Caleb said. “If I can be put on a horse, I reckon I can ride it to Santa Fe.”

There was anger in his voice. While they all watched, he managed to get to his feet. Even crippled he was taller than Salazarand he was determined not to die. Call was surprised by the man’s determination.

“If he’d been that determined to fight, we wouldn’t be prisoners,” he whispered to Gus.

“He ain’t determined for us … he’s determined for himself,” Gus pointed out.

Salazar, though, was out of patience.

“I cannot take you, Colonel,” he said, “and I cannot send you back, either. If I sent you with a few men, Gomez would find you again, and this time he would do worse.”

“I’ll take that chance,” Caleb said.

“But I won’t take it, Colonel,” Salazar said, drawing his pistol. “You are a brave officerit is time to finish yourself.”

The troops grew silent, when Salazar drew his pistol. Caleb Cobb was balanced on one leg; the other foot scarcely touched the ground. Call saw the anger rise in his face; for a second he expected Caleb to go for Salazar. But after a second, Caleb controlled himself.

“All right,” he said. “I never expected to die in a goddamn desert. I’m a seaman. I ought to be on my boat.”

“I know you were a great pirate,” Salazar said, relieved that the man was taking matters calmly. “You stole much treasure from the King of Spain.”

“I did, and lost it all at cards,” Caleb said. “I know you need to travel, Captain. Give me your pistol and I’ll finish it, and you can be on your way.”

“Would you like privacy?” Salazar askedhe still held the pistol.

“Why, nonot specially,” Caleb said, in a normal voice. “These wild Texas boys are all mad at me for surrendering. They’ll hang me, if they get the chance. It will amuse me to cheat ‘em, by shooting myself.”

“All right,” Salazar said.

“How was that you said I ought to do it, Wallace?” Caleb asked. “Are you here, Wallace? I know you think there’s a sure wayI want to take the sure way.”

“Through the eyeball,” Bigfoot said.

“It’ll have to be through the eye hole,” Caleb said. “I’m all out of eyeballs.”

“Well, that will do just as well, Colonel,” Bigfoot said.

“I’ll take the pistol now, if you please,” Caleb said, in a pleasant, normal voice.

“Adios, Colonel,” Salazar said, handing Caleb the pistol.

Caleb immediately turned the pistol on Salazar and shot him the Captain fell backward, clutching his throat.

“Rush ‘em, boysget their guns,” Caleb said. “I’ll take down a few.”

But in his blindness, Caleb Cobb fired toward the Texans, not the Mexicans. Two shots went wild, while the Texans ducked.

“Hell, he’s turned around, he’s shooting at us!” Long Bill said, as he ducked.

Before Caleb could fire a fourth time, the Mexican soldiers recovered from their shock and cut him down. As he fell, he fired a last shotShadrach, who had been standing calmly by Matilda, fell backwards, stiffly. He was dead before he had time to be surprised.

“Oh no! no! not my Shad,” Matilda cried, squatting down by Shadrach.

The Mexican soldiers continued to pour bullets into Caleb Cobb the corpse had more than forty bullets in it, when it was buried. But the Texans had lost interest in CalebBigfoot ripped open Shadrach’s shirt, hoping the old man was stunned but not dead. But the bullet had taken Shadrach exactly in the heart.

“What a pity,” Captain Salazar said. He was bleeding profusely from the wound in his throatthe wound, though, was only a crease.

“Shad, Shad!” Matilda said, trying to get the old man to answer but Shadrach’s lips didn’t quiver.

“This man had walked the dead man’s walk,” Salazar said. “He might have guided us. Your Colonel was already dead when he shot himI suppose his finger twitched. We are having no luck today.”

“Why, you’re having plenty of luck, Captain,” Bigfoot said. “If that bullet had hit your neck a fraction to the left, you’d be as dead as Shad.”

“True,” Salazar said. “I was very foolish to give Colonel Cobb my gun. He was a man like Gomezhe knew no law.”

When Matilda Roberts saw that Shadrach was dead, she began to wail. She wailed as loudly as her big voice would let her. Her cries echoed off a nearby buttemany men felt their hair stand up when the echo brought back the sound of a woman wailing in the desert. Many of the Mexican soldiers crossed themselves.

“Now, Matty,” Bigfoot said, kneeling beside and putting his big arm around her. “Now, Matty, he’s gone and that’s the sad fact.”

“I can’t bear it, he was all I had,” Matilda said, her big bosom, wet already with tears, heaving and heaving.

“It’s sad, but it might be providential,” Bigfoot said. “Shadrach wasn’t well, and we have to cross the Big Dry. I doubt Shad would have made it. He’d have died hard, like some of us will.”

“Don’t tell me that, I want him aliveI just want him alive,” Matilda said.

She cried on through the morning, as graves were dug. There were a dozen men to bury, and the ground was hard. Captain Salazar sat with his back to a wagon wheel as the men dug the graves. He was weak from loss of blood. He had reloaded his pistol, and kept it in his hand all day, afraid the brief commotion might encourage the Texans to rebel.

His caution was justified. Stirred by the shooting, several of the boys talked of making a fight. Blackie Slidell was for it, and also Jimmy Tweedboth men had had enough of Mexican rule.

Gus listened, but didn’t encourage the rebellion. His friend Call had collapsed, from being made to walk when he wasn’t able. He was weaker than Salazar, and more badly injured. Escape would mean leaving him behindand Gus had no intention of leaving him behind. Besides, Matilda was incoherent with grieffour men had to pull her loose from Shadrach’s body, before it could be buried. The Mexican soldiers might mostly be boys, but they had had the presence of mind to kill Caleb Cobbsince they had all the guns, rebellion or escape seemed a long chance.

They had planned to shelter for the night in a village called SanSaba, but the burials and the weakness of Captain Salazar kept them in place until it was too late to travel more than a few miles.

That night a bitter wind came from the north, so cold that the men, Mexicans and Texans alike, couldn’t think of anything but warmth. The Texans even agreed to be tied, if they could only share the campfires. No one slept. The wind keened through the camp. Matilda, having no Shadrach to care for, covered Call with her body. Before dawn, they had burned both wagons.

“How far’s that village, Captain?” Bigfoot askeddawn was grey, and the wind had not abated.

“Too fartwenty miles,” Captain Salazar said.

“We have to make it tomorrow, we’ve got nothing else to burn,” Bigfoot said.

“Call will die if he has to sleep in the open without no fire,” Matilda said.

“Let’s lope along, then, boys,” Bigfoot said.

“I’ll help you with Woodrow, Matty,” Gus said. “He looks poorly to me.”

“Not as poorly as my Shad,” Matilda said. Between them, they got Call to his feet.

ALL DAY CALL STRUGGLED through the barren country. The freezing wind seemed to slide through the slices in his back and sides; it seemed to blow right into him. He couldn’t feel his feet, they were so cold. Gus supported him some; Matilda supported him some; even Long Bill Coleman helped out.

“How’d it get so damn cold?” Jimmy Tweed muttered, several times. “I never been no place where it was this cold. Even that snow wasn’t this cold.”

“You ought to leave me,” Call said. “I’m slowing you down.” It grated on him, that he had to be helped along.

“Maybe there’ll be a bunch of goats in this village,” Gus said. He was very hungry. The wind in his belly made the wind from the north harder to bear. He had always had a fondness for goat meatin his imagination, the village they were approaching was a wealthy center of goat husbandry, with herds in the hundreds of fat, tasty goats grazing in the desert scrub. He imagined afeast in which the goats they were about to eat were spitted over a good fire, dripping their juices into the flame. Yet, as he struggled on, it became harder to trust in his own imaginings, because there was no desert scrub. There was nothing but the rough earth, with only here and there a cactus or low thornbush. Even if there were goats, there would be no firewood, no fire to cook them over.

Captain Salazar rode in silence, in pain from his neck wound. Now and then the soldiers walking beside him would rub their hands against his horse, pressing their hands into the horsehair to gain a momentary warmth.

Except when she was helping Call, Matilda walked alone. She cried, and the tears froze on her cheeks and on her shirt. She wanted to go back and stay with Shadrachshe could sit by his grave until the wind froze her, or until the Indians came, or a bear. She wanted to be where he had diedand yet she could not abandon the boy, Woodrow Call, whose wounds were far from healed. He still might take a deep infection; even if he didn’t, he might freeze if she was not there to warm him.

The cold had had a bad effect on Johnny Carthage’s sore leg. He struggled mightily to keep up, and yet as the day went on he fell farther and farther behind. Most of the Mexican soldiers were freezing, too. They had no interest in the lame Texan, who dropped back into their ranks, and then behind their ranks.

“I’ll catch you, I’ll catch you,” Johnny said, over and over, though the Mexicans weren’t listening.

By midafternoon some of the other Texans had begun to lag, and many of the Mexican infantrymen as well. The marchers were strung out over a milethen, over two. Bigfoot went ahead, hoping for a glimpse of the village they were seekingbut he saw nothing, just the level desert plain. Behind them there was a low bank of dark cloudsperhaps it meant more snow. He felt confident that he himself could weather the night, even without fire, but he knew that many of the men wouldn’tthey would freeze, unless they reached shelter.

“I wonder if we even know where we’re goingwe might be missing that town,” Bigfoot said, to Gus. “If we miss it we’re in for frosty sleeping.““I don’t want to miss itI hope they have goats,” Gus said. He was half carrying Call at the time.

Bigfoot dropped back to speak with Salazarthe Captain was plodding on, but he was glassy eyed from pain and fatigue.

“Captain, I’m fearful,” Bigfoot said. “Have you been to this place what’s it called?”

“San Saba,” Salazar said. “No, I have not been to it.”

“I hope it’s there,” Bigfoot said. “We’ve got some folks that won’t make it through the night unless we find shelter. Some of them are my boys, but quite a few of them are yours.”

“I know that, but I am not a magician,” Salazar said. “I cannot make houses where there are no houses, or trees where there are no trees.”

“Why don’t you let us go, Captain?” Bigfoot asked. “We ain’t all going to survive this. Why risk your boys just to take us south? Caleb Cobb was the man who thought up this expedition, and he’s dead.”

Captain Salazar rode on, still glassy eyed, for some time before answering. When he did speak, his voice was cracked and hoarse.

“I cannot let you go, Mr. Wallace,” he said. “I’m a military man, and I have my orders.”

“Dumb orders, I’d say,” Bigfoot said. “We ain’t worth freezing to death for. We haven’t killed a single one of your people. All we’ve done is march fifteen hundred miles to make fools of ourselves, and now we’re in a situation where half of us won’t live even if you do let us go. What’s the point?”

Salazar managed a smile, though the effort made his face twist in pain.

“I didn’t say my orders were intelligent, merely that they were mine,” he said. “I’ve been a military man for twenty years, and most of my orders have been foolish. I could have been killed many times, because of foolish orders. Now I have been given an order so foolish that I would laugh and cry if I weren’t so cold and in such pain.”

Bigfoot said nothing. He just watched Salazar.

“Of course, you are right,” Salazar went on. “You marched a long way to make fools of yourselves and you have done no harm to my people. If you had, by the way, you would have been shot then all of us would have been spared this wind. But my orders are still mine. I have to take you to El Paso, or die trying.”

. “It might be the latter, Captain,” Bigfoot said. “I don’t like that cloud.”

Soon, a driving sleet peppered the men’s backs. As dusk fell, it became harder to seethe sleet coated the ground and made each step agony for those with cold feet.

“I fear we’ve lost Johnny,” Bigfoot said. “He’s back there somewhere, but I can’t see him. He might be a mile backor he might be froze already.”

“I’ll go back and get him,” Long Bill said.

“I wouldn’t,” Bigfoot said. “You need all you’ve got, to make it yourself.”

“No, Johnny’s my companero” Long Bill said. “I reckon I’ll go back. If we die tonight, I expect I should be with Johnny.”

It took Gus and Matilda both to keep Call going. The sleet thickened on the ground, until it became too slippery for him to manage. Finally, the two of them carried him, his arms over their shoulders, his body warmed between their bodies.

As the darkness came on and the sleet blew down the wind like bird shot, doom was in the mind of every man. All of them, even Bigfoot Wallace, veteran of many storms, felt that it was likely that they would die during the night. Long Bill had gone loyally back into the teeth of the storm, to find his companero, Johnny Carthage. Captain Salazar was slumped over the neck of his horse, unconscious. His neck wound had continued to bleed until he grew faint and passed out. The Mexican soldiers walked in a cluster, except for those who lagged. They had only one lantern; the light illumined only a few feet of the frigid darkness. As the darkness deepened, the cold increased, and the men began to give up. Texan and Mexican alike came to a moment of resignationthey ceased to be able to pick their feet up and inch forward over the slippery ground. They thought but to rest a moment, until their energies were restored; but the rest lengthened, and they did not get up. The sleet coated their clothes. At first they sat, their backs to the wind and the sleet. Then the will to struggle left them, and they lay down and let the sleet cover them.