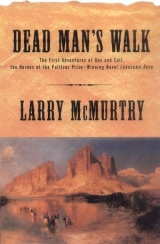

Текст книги "Dead Man's Walk"

Автор книги: Larry McMurtry

Жанр:

Вестерны

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 1 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Larry McMurtry

DEAD MAN’S WALK

1.

MATILDA JANE ROBERTS WAS naked as the air. Known throughout south Texas as the Great Western, she came walking up from the muddy Rio Grande holding a big snapping turtle by the tail. Matilda was almost as large as the skinny little Mexican mustang Gus McCrae and Woodrow Call were trying to saddle-break. Call had the mare by the ears, waiting for Gus to pitch the saddle on her narrow back, but the pitch was slow in coming. When Call glanced toward the river and saw the Great Western in all her plump nakedness, he knew why: young Gus McCrae was by nature distractable; the sight of a naked, two-hundred-pound whore carrying a full-grown snapping turtle had captured his complete attention, and that of the rest of the Ranger troop as well.

“Look at that, Woodrow,” Gus said. “Matty’s carrying that old turtle as if it was a basket of peaches.”

“I can’t look,” Call said. “I’ll lose my grip and get kickedand I’ve done been kicked.” The mare, small though she was, had already displayed a willingness to kick and bite. Call knew that if he loosened his grip on her ears even slightly, he could count on getting kicked, or bitten, or both.

Long Bill Coleman, lounging against his saddle only a few yards from where the two young Rangers were struggling with the little mustang, watched Matilda approach, with a certain trepidation. Although it was only an hour past breakfast, he was already drunk. It seemed to Long Bill, in his tipsy state, that the Great Western was walking directly toward him with her angry catch. It might be that she meant to use the turtle as some kind of weaponor so Long Bill surmised. Matilda Roberts despised debt, and carried grudges freely and at length. Bill knew himself to be considerably in arrears, the result of a persistent lust coupled with a vexing string of losses at cards. At the moment, he didn’t have a red cent and knew that he was unlikely to have one for days, or even weeks to come. If Matilda, who was whimsical, chose to call his debt, his only recourse might be to run; but Long Bill was in no shape to run, and in any case, there was no place to run to that offered the least prospect of refuge. The Rangers were camped on the Rio Grande, west of the alkaline Pecos. They were almost three hundred miles from the nearest civilized habitation, and the country between them and a town was not inviting.

“When’s the next payday, Major?” Long Bill inquired, glancing at his leader, Major Randall Chevallie.

“That woman acts like she might set that turtle on me,” he added, hoping that Major Chevallie would want to issue an order or something. Bill knew that there were military men who refused to allow whores within a hundred feet of their campeven whores not armed with snapping turtles.

Major Chevallie had only spent three weeks at West Pointhe left because he found the classes boring and the discipline vexing. He nonetheless awarded himself the rank of major after a violent scrape in Baltimore convinced him that civilian life hemmed a man in with such a passel of legalities that it was no longer worth pursuing. Randall Chevallie hid on a ship, and the ship took him to Galveston; upon disembarking at that moist, sandy port, he declared himself a major and had been a major ever since.

Now, except for the two young Rangers who were attempting to saddle the Mexican mare, his whole troop was drunk, the result of an incautious foray into Mexican territory the day before. They had crossed the Rio Grande out of boredom, and promptly captured a donkey cart containing a few bushels of hard corn and two large jugs of mescal, a liquor of such potency that it immediately unmanned several of the Rangers. They had been without spirits for more than a monththey drank the mescal like water. In fact, it tasted a good deal better than any water they had tasted since crossing the Pecos.

The mescal wasn’t water, though; two men went blind for awhile, and several others were troubled by visions of torture and dismemberment. Such visions, at the time, were not hard to conjure up, even without mescal, thanks to the folly of the unfortunate Mexican whose donkey cart they had captured. Though the Rangers meant the man no harmor at least not much harmhe fled at the sight of gringos and was not even out of earshot before he fell into the hands of Comanches or Apaches: it was impossible to tell from his screams which tribe was torturing him. All that was known was that only three warriors took part in the torturing. Bigfoot Wallace, the renowned scout, returned from a lengthy look around and reported seeing the tracks of three warriors, no more. The tracks were heading toward the river.

Many Rangers thought Bigfoot’s point somewhat picayune, since the Mexican could not have screamed louder if he had been being tortured by fifty menthe screams made sleep difficult, not to mention short. The Great Western didn’t earn a cent all night. Only young Gus McCrae, whose appetite for fornication admitted no checks, approached Matilda, but of course young McCrae was penniless, and Matilda in no mood to offer credit.

“You better turn that mare loose for awhile,” Gus advised. “Matty’s coming with that big turtleI don’t know what she means to do with it.”

“Can’t turn loose,” Call said, but then he did release the mare, jumping sideways just in time to avoid her flailing front hooves. It was clear to him that Gus had no intention of trying to saddle the mare, not anytime soon. When there was a naked whore to watch, Gus was unlikely to want to do much of anything, except watch the whore.

“Major, what about payday?” Long Bill inquired again.

Major Chevallie cocked an eyebrow at Long Bill Coleman, a man noted for his thorough laziness.

“Why, Bill, the mail’s undependable, out here beyond the Pecos,” the Major said. “We haven’t seen a mail coach since we left San Antonio.”

“That whore with the dern turtle wants to be paid now,” one-eyed Johnny Carthage speculated.

“I’ve never seen a whore bold enough to snatch an old turtle right out of the Rio Grande river,” Bob Bascom said. In his opinion, it had been quite unmilitary for the Major to allow Matilda Roberts to accompany them on their expedition; though how he would have stopped her, short of gunplay, was not easy to say. Matilda had simply fallen in with them when they left the settlements. She rode a large grey horse named Tom, who lost flesh rapidly once they were beyond the fertile valleys. Matilda had no fear of Indians, or of anything else, not so far as Bob Bascom was aware. She helped herself liberally to the Rangers’ grub, and conducted business on a pallet she spread in the bushes, when there were bushes. Bob had to admit that having a whore along was a convenience, but he still considered it unmilitary, though he was not so incautious as to give voice to his opinion.

Major Randall Chevallie was of uncertain temper at best. Rumour had it that he had, on occasions, conducted summary executions, acting as his own firing squad. His pistol was often in his hand, and though his leadership was erratic, his aim wasn’t. He had twice brought down running antelope with his pistolmost of the Rangers couldn’t have hit a running antelope with a rifle, or even a Gatling gun.

“That whore didn’t snatch that turtle out of the river,” Long Bill commented. “I seen that turtle sleeping on a rock, when I went to wash the puke off myself. She just snuck up on it and picked it off that rock. Look at it snap at her. Now she’s got it mad!”

The snapper swung its neck this way and that, working its jaws; but Matilda Roberts was holding it at arm’s length, and its jaws merely snapped the air.

“What next?” Gus said, to Call.

“I don’t know what next,” Call said, a little irritated at his friend. Sooner or later they would have to have another try at saddling the marea chancy undertaking.

“Maybe she means to cook it,” Call added.

“I have heard of slaves eating turtle,” Gus said. “I believe they eat them in Mississippi.”

“Well, I wouldn’t eat one,” Call informed him. “I’d still like to get a saddle on this mare, if you ain’t too busy to help.”

The mare was snubbed to a low mesquite treeshe wound herself tighter and tighter, as she kicked and struggled.

“Let’s see what Matilda’s up to first,” Gus said. “We got all day to break horses.”

“All right, but you’ll have to take the ears, this time,” Call said. “I’ll do the saddling.”

Matilda swung her arm a time or two and heaved the big turtle in the general direction of a bunch of Rangersthe boys were cleaning their guns and musing on their headaches. They scattered like quail when they saw the turtle sailing through the air. It turned over twice and landed on its back, not three feet from the campfire.

Bigfoot Wallace squatted by the firehe had just finished pouring himself a cup of coffee. It was chickory coffee, but at least it was black. Bigfoot paid the turtle no attention at allMatty Roberts had always been somewhat eccentric, in his view. If she wanted to throw snapping turtles around, that was her business. He himself was occupied with more urgent concerns, one of them being the identity of the three warriors who had tortured the Mexican to death. A few hours after coming across their tracks he had dozed off and dreamed a disturbing dream about Indians. In his dream Buffalo Hump was riding a spotted horse, while Gomez walked beside him. Buffalo Hump was the meanest Comanche anyone had ever heard of, and Gomez the meanest Apache. The fact that a Comanche killer and an Apache killer were traveling together, in his dream, was highly unpleasant. Never before, that he could remember, had he had a dream in which something so unlikely happened. He almost felt he should report the dream to Major Chevallie, but the Major, at the moment, was distracted by Matilda Roberts and her turtle.

“Good morning, Miss Roberts, is that your new pet?” the Major inquired, when Matilda walked up.

“Nope, that’s breakfastturtle beats bacon,” Matilda said. “Has anybody got a shirt I can borrow? I left mine out by the pallet.“She had strolled down to the river naked because she felt like having a wash in the cold’water. It wasn’t deep enough to swim in, but she gave herself a good splashing. The old snapper just happened to be lazing on a rock nearby, so she grabbed it. Half the Rangers were scared of Matilda anyway, some so scared they would scarcely look at her, naked or clothed. The Major wasn’t scared of her, nor was Bigfoot or young Gus; the rest of the men, in her view, were incompetents, the kind of men who were likely to run up debts and get killed before they could pay them. She sailed the snapper in their direction to let them know she expected honest behaviour. Going naked didn’t hurt, either. She was big, and liked it; she could punch most men out, if she had to, and sometimes she had to; her dream was to get to California and own a fine bordello, which was why she fell in with the first Ranger troop going west. It was a scraggly little troop, composed mostly of drunks and shiftless ramblers, but she took it and was making the best of it. The alternative was to wait in Texas, get old, and never own a bordello in California.

At her request several Rangers immediately began to take off their shirts, but Bigfoot Wallace made no move to remove his, and his was the only shirt large enough to cover much of Matty Roberts.

“I guess you won’t be sashaying around naked much longer, Matty,” he observed, sipping his chickory.

“Why not? I ain’t stingy about offering my customers a look,” Matilda said, rejecting several of the proffered shirts.

Bigfoot nodded toward the north, where a dark tone on the horizon contrasted with the bright sunlight.

“One of our fine blue northers is about to whistle in,” he informed her. “You’ll have icicles hanging off your twat, in another hour, if you don’t cover it up.”

“I wouldn’t need to cover it up if anyone around here was prosperous enough to warm it up,” Matilda said, but she did note that the northern horizon had turned a dark blue. Several Rangers observed the same fact, and began to pull on long Johns or other garments that might be of use against a norther. Bigfoot Wallace was known to have an excellent eye for weather. Even Matilda respected itshe strolled over to her pallet and pulled on a pair of blacksmith’s overalls that she had taken in payment for a brief engagement in Fredericksburg. She had a tattered capote, acquired some years earlier in Pennsylvania, and she put that on too. A blue norther could quickly suck the warmth out of the air, even on a nice sunny day.

“Well, we’ve conquered a turtle, I guess,” Major Chevallie said, standing up. “I suppose that Mexican diedI don’t hear much noise from across the river.”

“If he’s lucky, he died,” Bigfoot said. “It was just three Indians Comanches, I’d figure. I doubt three Comanches would pause more than one night to cut up a Mexican.”

About that time Josh Corn and Ezekiel Moody came walking back to camp from the sandhill where they had been standing guard. Josh Corn was a little man, only about half the size of his tall friend. Both were surprised to see a sizable snapping turtle kicking its legs in the air, not much more than arm’s length from the coffeepot.

“Why’s everybody dressing up, is there going to be a parade?” Josh asked, noting that several Rangers were in the process of pulling on clothes.

“That Mexican didn’t have no way to kill himself,” Bob Bascom remarked. “He didn’t have no gun.”

“No, but he had a knife,” Bigfoot reminded him. “A knife’s adequate, if you know where to cut.”

“Where would you cutI’ve wondered,” Gus asked, abruptly leaving Call to contemplate the Mexican mustang alone. He was a Ranger on the wild frontier now and needed to imbibe as much technical information as possible about methods of suicide, when in danger of capture by hostiles with a penchant for torture.

“No Comanche’s going to be quick enough to sew up your jugular vein, if you whack it through in two or three places,” Bigfoot said. Aware that several of the Rangers were inexpert in such matters, he stretched his long neck and put his finger on the spot where the whacking should be done.

“It’s right here,” he said. “You could even poke into it with a big mesquite thorn, or whack at it with a broken bottle, if you’re left without no knife.”

Long Bill Coleman felt a little queasy, partly because of the mescal and partly from the thought of having to stick a thorn in his neck in order to avoid Comanche torture.“Me, I’ll shoot myself in the head if I’ve got time,” Long Bill said. “Well, but that can go wrong,” Bigfoot informed him. Once set in an instructional direction, he didn’t like to turn until he had given a thorough lecture. Bigfoot considered himself to be practical to a faultif a man had to kill himself in a hurry, it was best to know exactly how to proceed.

“Don’t go sticking no gun in your mouth, unless it’s a shotgun,” he advised, noting that Long Bill looked a little green. Probably the alkaline water didn’t agree with him.

“Why not, it’s hard to miss your head if you’ve got a gun in your mouth,” Ezekiel Moody commented.

“No, it ain’t,” Bigfoot said. “The bullet could glance off a bone and come out your ear. You’d still be healthy enough that they could torture you for a week. Shove the barrel of the gun up against an eyeball and pullthat’s sure. Your brains will get blown out the back of your headthen if some squaw comes along and chews off your balls and your pecker, you won’t know the difference.”

“My, this is a cheery conversation,” Major Chevallie said. “I wish Matilda would come back and remove this turtle.”

“I’d like to go back and have another look at them tracks,” Bigfoot said. “It was about dark when I seen them. Another look couldn’t hurt.”

“It could hurt if the Comanches that got that Mexican caught you,” Josh Corn remarked.

“Why, those boys are halfway to the Brazos, by now,” Bigfoot said, just as Matilda returned to the campfire. She squatted down by the turtle and watched it wiggle, a happy expression on her broad face. She had a hatchet in one hand and a small bowie knife in the other.

“Them turtles don’t turn loose of you till it thunders, once they got aholt of you,” Ezekiel said. Matilda Roberts ignored this hackneyed opinion. She caught the turtle right by the head, held its jaws shut, and slashed at its neck with the little bowie knife. The whole company watched, even Call. Several of the men had traveled the Western frontier all their lives. They considered themselves to be experienced men, but none of them had ever seen a whore decapitate a snapping turtle before.

Blackie Slidell watched Matilda slash at the turtle’s neck with a glazed expression. The mescal had caused him to lose his vision entirely, for several hoursin fact, it was still somewhat wobbly. Blackie had an unusual birthmarkhis right ear was coal black, thus his name. Although he couldn’t see very well, Blackie was not a little disturbed by Bigfoot’s chance remark about the chewing propensities of Comanche squaws. He had long heard of such things, of course, but had considered them to be unfounded rumour. Bigfoot Wallace, though, was the authority on Indian customs. His comment could not be ignored, even if everybody else was watching Matilda cut the head off her turtle.

“Hell, if we see Indians, let’s kill all the squaws,” Blackie said, indignantly. “They got no call to be behaving like that.”

“Oh, there’s worse than that happens,” Bigfoot remarked casually, noting that the turtle’s blood seemed to be greenif it had blood. A kind of green ooze dripped out of the wound Matilda had made. She herself was finding the turtle’s neck a difficult cut. She gave the turtle’s head two or three twists, hoping it would snap off like a chicken’s would have, but the turtle’s neck merely kinked, like a thick black rope.

“What’s worse than having your pecker chewed off?” Blackie inquired.

“Oh, having them pull out the end of your gut and tie it to a dog,” Bigfoot said, pouring himself more chickory. “Then they chase the dog around camp for awhile, until about fifty feet of your gut is strung out in front of you, for brats to eat.”

“To eat?” Long Bill asked.

“Why yes,” Bigfoot said. “Comanche brats eat gut like ours eat candy.”

“Whew, I’m glad I wasn’t especially hungry this morning,” Major Chevallie commented. “Talk like this would unsettle a delicate stomach.”

“Or they might run a stick up your fundament and set it on fire that way your guts would done be cooked when they pull them out,” Bigfoot explained.

“What’s a fundament?” Call asked. He had had only one year of schooling, and had not encountered the word in his speller. He kept the speller with him in his saddlebag, and referred to it now and then when in doubt about a letter or a word.Bob Bascom snorted, amused by the youngster’s ignorance.

“It’s a hole in your body and it ain’t your nose or your mouth or your goddamn ear,” Bob said. “I’d have that little mare broke by now, if it was me doing it.”

Call smarted at the rebukehe knew they had been lax with the mare, who had now effectively snubbed herself to the little tree. She was trembling, but she couldn’t move far, so he quickly swung the saddle in place and held it there while she crow-hopped a time or two.

Matilda Roberts sweated over her task, but she didn’t give up. The first gusts of the norther scattered the ashes of the campfire. Major Chevallie had just squatted to refill his cuphis coffee soon had a goodly sprinkling of sand. When the turtle’s head finally came off, Matilda casually pitched it in the direction of Long Bill, who jumped up as if she’d thrown him a live rattler.

The turtle’s angry eyes were still open, and its jaws continued to snap with a sharp click.

“It ain’t even dead with its head off,” Long Bill said, annoyed.

Shadrach, the oldest Ranger, a tall, grizzled specimen with a cloudy past, walked over to the turtle’s head and squatted down to study it. Shadrach rarely spoke, but he was by far the most accurate rifle shot in the troop. He owned a fine Kentucky rifle, with a cherry-wood stock, and was contemptuous of the bulky carbines most of the troop had adopted.

Shadrach found a little mesquite stick and held it in front of the turtle’s head. The turtle’s beak immediately snapped onto the stick, but the stick didn’t break. Shadrach picked up the little stick with the turtle’s head attached to it and dropped it in the pocket of his old black coat.

Josh Corn was astonished.

“Why would you keep a thing like that?” he asked Shadrach, but the old man took no interest in the question.

“Why would he keep a smelly old turtle’s head?” Josh asked Bigfoot Wallace.

“Why would Gomez raid with Buffalo Hump?” Bigfoot asked. “That’s a better question.”

Matilda, by this time, had hacked through the turtle shell with her hatchet and was cutting the turtle meat into strips. Watching her slice the green meat caused Long Bill Coleman to get the queasy feeling again. Young Call, though nicked by a rear hoof, had succeeded in cinching the saddle onto the Mexican mare.

Major Chevallie was sipping his ashy coffee. Already the new wind from the north had begun to cut. He hadn’t been paying much attention to the half-drunken campfire palaver, but between one sip of coffee and the next, Bigfoot’s question brought him out of his reverie.

“What did you say about Buffalo Hump?” he asked. “I wouldn’t suppose that scoundrel is anywhere around.”

“Well, he might be,” Bigfoot said.

“But what was that you said, just now?” the Major asked. “It’s hard to concentrate, with Matilda cutting up this ugly turtle.”

“I had a dern dream,” Bigfoot admitted. “In my dream Gomez was raiding with Buffalo Hump.”

“Nonsense, Gomez is Apache,” the Major said.

Bigfoot didn’t answer. He knew that Gomez was Apache, and that Apache didn’t ride with Comanchethat was not the normal order of things. Still, he had dreamed what he dreamed. If Major Chevallie didn’t enjoy hearing about it, he could sip his coffee and keep quiet.

The whole troop fell silent for a moment. Just hearing the names of the two terrible warriors was enough to make the Rangers reflect on the uncertainties of their calling, which were considerable.

“I don’t like that part about the guts,” Long Bill said. “I aim to keep my own guts inside me, if nobody minds.”

Shadrach was saddling his horsehe felt free to leave the troop at will, and his absences were apt to last a day or two.

“Shad, are you leaving?” Bigfoot asked.

“We’re all leaving,” Shadrach said. “There’s Indians to the north. I smell ‘em.”

“I thought I still gave the orders around here,” Major Chevallie said. “I don’t know why you would have such a dream, Wallace. Why would those two devils raid together?”

“I’ve dreamt prophecy before,” Bigfoot said. “Shad’s right about the Indians. I smell ‘em too.”

“What’s thiswhere are they?” Major Chevallie asked, just as the norther hit with its full force. There was a general scramble for guns and cover. Long Bill Coleman found the anxiety too much for his overburdened stomach. He grabbed his rifle, but then had to bend and puke before he could seek cover.

The cold wind swirled white dust through the camp. Most of the Rangers had taken cover behind little hummocks of sand, or chaparral bushes. Only Matilda was unaffected; she continued to lay strips of greenish turtle meat onto the campfire. The first cuts were already dripping and crackling.

Old Shadrach mounted and went galloping north, his long rifle across his saddle. Bigfoot Wallace grabbed a rifle and vanished into the sage.

“What do we do with this mare, Gus?” Call asked. He had only been a Ranger six weekshis one problem with the work was that it was almost impossible to get precise instructions in a time of crisis. Now he finally had the Mexican mare saddled, but everyone in camp was lying behind sandhills with their rifles ready. Even Gus had grabbed his old gun and taken cover.

Major Chevallie was attempting to unhobble his horse, but he had no dexterity and was making a slow job of it.

“You boys, come help me!” he yelledfrom the precipitate behaviour of Shadrach and Bigfoot, the most experienced men in the troop, he assumed that the camp was in danger of being overrun.

Gus and Call ran to the Major’s aid. The wind was so cold that Gus even thought it prudent to button the top button of his flannel shirt.

“Goddamn this wind!” the Major said. During breakfast he had been rereading a letter from his dear wife, Jane. He had read the letter at least twenty times, but it was the only letter he had with him and he did love his winsome Jane. When the business about Gomez and Buffalo Hump came up he had casually stuffed the letter in his coat pocket, but he didn’t get it in securely, and now the whistling wind had snatched it. It was a long .letterhis dear Jane was lavish with detail of circumstances back in Virginiaand now several pages of it were blowing away, in the general direction of Mexico.

“Here, boys, fetch my letter!” the Major said. “I can’t afford to lose my letter. I’ll finish saddling this horse.”

Call and Gus left the Major to finish cinching his saddle on his big sorrel and began to chase the letter, some of which had sailedquite a distance downwind. Both of them kept looking over their shoulders, expecting to see the Indians charging.

Call had not had time to fetch his riflehis only weapon was a pistol.

Thanks to his efforts with the mare, the talk of torture and suicide had been hard to follow. Call liked to do things correctly, but was in doubt as to the correct way to dispatch himself, should he suddenly be surrounded by Comanches.

“What was it Bigfoot said about shooting out your brains?” he asked Gus, his lanky pal.

Gus had run down four pages of the Major’s lengthy letter. Call had three pages. Gus didn’t seem to be particularly concerned about the prospect of Comanche capturehis nonchalant approach to life could be irksome in times of conflict.

“I’d go help Matty clean her turtle if I thought she’d give me a poke,” Gus said.

“Gus, there’s Indians coming,” Call said. “Just tell me what Bigfoot said about shooting out your brains.

“That whore don’t need no help with that turtle,” he added.

“Oh, you’re supposed to shoot through the eyeball,” Gus said. “I’ll be damned if I would, though. I need both eyes to look at whores.”

“I should have kept my rifle handier,” Call said, annoyed with himself for having neglected sound procedure. “Do you see any Indians yet?”

“No, but I see Josh Corn taking a shit,” Gus said, pointing at their friend Josh. He was squatting behind a sage bush, rifle at the ready, while he did his business.

“I guess he must think it’s his last chance before he gets scalped,” Gus added.

Major Chevallie jumped on his sorrel and started to race after Shadrach, but had scarcely cleared the camp before he reined in his horse. Call could just see him, in the swirling dustthe plain to the north of the camp had become a wall of sand.

“I wonder how we can get some moneyI sure do need a poke,” Gus said. He had turned his back to the wind and was casually reading the Major’s letter, an action that shocked Call.

“That’s the Major’s letter,” he pointed out. “You got no business reading it.”

“Well, it don’t say much anyway,” Gus said, handing the pages to Call. “I thought it might be racy, but it ain’t.”

“If I ever write a letter, I don’t want to catch you reading it,” Call said. “I think Shad’s coming back.” His eyes were stinging, from staring into the dust.

There seemed to be figures approaching camp from the north. Call couldn’t make them out clearly, and Gus didn’t seem to be particularly interested. Once he began to think about whores he had a hard time pulling his mind off the subject.

“If we could catch a Mexican we could steal his moneyhe might have enough that we could buy quite a few pokes,” Gus said, as they strolled back to camp.

Major Chevallie waited on his sorrel, watching. Two figures seemed to be walking. Then Bigfoot fell in with them. Shadrach appeared on his horse, a few steps behind the figures.

All around the camp Rangers began to stand up and dust the sand off their clothes. Matilda, unaffected by the crisis, was still cooking her turtle. The bloody shell lay by the campfire. Call smelled the sizzling meat and realized he was hungry.

“Why, it’s just an old woman and a boy,” he said when he finally got a clear view of the two figures trudging through the sandstorm, flanked on one side by Shadrach and on the other by Bigfoot Wallace.

“Shoot, I doubt either one of them has got a cent on them,” Gus said. “I think we ought to sneak off across the river and catch a Mexican while it’s still early.”

“Just wait,” Call said. He was anxious to see the captives, if they were captives.

“I swear,” Long Bill said. “I think that old woman’s blind. That boy’s leading her.”

Long Bill was right. A boy of about ten, who looked more Mexican than Indian, walked slowly toward the campfire, leading an old white-haired Indian womanCall had never seen anyone who looked as old as the old woman.

When they came close enough to the fire to smell the sizzling meat, the boy began to make a strange sound. It wasn’t speech, exactlyit was more like a moan.

“What’s he wanting?” Matilda askedshe was unnerved by the sound.

“Why, a slice or two of your turtle meat, I expect,” Bigfoot said. “More than likely he’s hungry.” “Then why don’t he ask?” Matilda said.

“He can’t ask, Matilda,” Bigfoot said.

“Why not, ain’t he got a tongue?” Matilda asked.

“Nopeno tongue,” Bigfoot said. “Somebody cut it out.”

THE NORTH WIND BLEW harder, hurling the sands and soils of the great plain of Texas toward Mexico. It soon obliterated vision. Shadrach and Major Chevallie, mounted, could not see the ground. Men could not see across the campfire. Call found his rifle, but when he tried to sight, discovered that he could not see to the end of the barrel. The sand peppered them like fine shot, and it rode a cold wind. The horses could only turn their backs to it; so did the men. Most put their saddles over their heads, and their saddle blankets too. Matilda’s bloody turtle shell soon filled with sand. The campfire was almost smothered. Men formed a human wall to the north of it, to keep it from guttering out. Bigfoot and Shadrach tied bandanas around their facesLong Bill had a bandana but it blew away and was never found. Matilda gave up cooking and sat with her back to the wind, her head bent between her knees. The boy with no tongue reached into the guttering campfire and took two slices of the sizzling turtle meat. One he gave to the old blind womanalthough the meat was tough and scalding, he gulped his portion in only three bites.