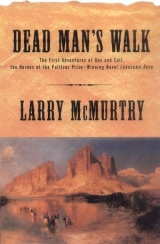

Текст книги "Dead Man's Walk"

Автор книги: Larry McMurtry

Жанр:

Вестерны

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 16 (всего у книги 29 страниц)

Call drew his knife and approached the animal from the other side. It had a short, thick neck, but he knew the big vein had to be somewhere in it; if he could cut the big vein the buffalo would eventually die, no matter how much praying and dancing the Comanches had done over it.

He stabbed and drew blood and so did Gus and Bigfootthey stabbed until their arms were tired of lifting their knives, until they were all three covered with blood. Finally, red and panting from their efforts, they all three gave up. They stood a foot from the buffalo, completely exhausted, unable to kill it.

As a last effort, Call drew his pistol, stuck it against the buffalo’s head just below the ear, and fired. The buffalo took one step forward and sank to its knees. All three men stepped back, thinking the animal would roll over, but it didn’t. Its head sank and it died, still on its knees.

“If only there was a creekI’d like to wash,” Gus said. He had never liked the smell of blood and was shocked to find himself covered with it, in a place where there was no possibility of washing.

They all sank down on the prairie grass and rested, too tired to cut up their trophy.

“How do Indians ever kill them?” Call asked, looking at the buffalo. It seemed to be merely resting, its head on its knees.

“Why, with arrowshow else?” Bigfoot asked.

Call said nothing, but once again he felt a sense of trespass. It had taken three men, with rifles, pistols, and knives, an hour to kill one beast; yet, Indians did it with arrows alonehe had watched them kill several on the floor of the Palo Duro Canyon.

“All buffalo ain’t this hard,” Bigfoot assured them. “I’ve never seen one this hard.”

“Dern, I wish I could wash,” Gus said.

BIGFOOT WALLACE TOOK ONLY the buffalo’s tongue and liver. The tongue he put in his saddlebag, after sprinkling it with salt; the liver he sliced and ate raw, first dripping a drop or two of fluid from the buffalo’s gallbladder on the slices of meat.

“A little gall makes it tasty,” he said, offering the meat to Call and Gus.

Call ate three or four bites, Gus only one, which he soon quickly spat out.

“Can’t we cook it?” he asked. “I’m hungry, but not hungry enough to digest raw meat.”

“You’ll be that hungry tomorrow, unless we’re lucky,” Bigfoot said.

“I’d just rather cook it,” Gus said, againit was clear from Bigfoot’s manner that he regarded the request as absurdly fastidious.

“I guess if you want to burn your clothes you might get fire enough to singe a slice or two,” Bigfoot saidhe gestured toward the empty plain around them. Nowhere within the reach of their eyes was there a plant, a bush, a tree that would yield even a stick of firewood. The plain was not entirely level, but it was entirely bare.

“What a goddamn place this is,” Gus said. “A man has to tote his own firewood, or else make do with raw meat.”

“No, there’s buffalo chips, if you want to hunt for them,” Bigfoot said. “I’ve cooked many a liver over buffalo chips, but there ain’t many buffalo out this way. I don’t feel like walking ten miles to gather enough chips to keep you happy.”

As they rode away from the dead buffalo, they saw two wolves trotting toward it. The wolves were a long way away, but the fact that there were two living creatures in sight on the plain was reassuring, particularly to Gus. He had been more comfortable in a troop of Rangers than he was with only Call and Bigfoot for company. They were just three human dots on the encircling plain.

Bigfoot watched the wolves with interest. Wolves had to have water, just as did men and women. The wolves didn’t look lank, eitherthere must be water within a few miles, if only they knew which way to ride.

“Wolves and coyotes ain’t far from being dogs,” he observed. “You’ll always get coyotes hanging around a campthey like people or at least they like to eat our leavings. The Colonel ought to catch him a coyote pup or two and raise them to hunt for him. It’d take the place of that big dog you dropped.”

Call thought they were all likely to die of starvation. It was gallant of Bigfoot to speculate about the Colonel and his pets when they were in such a desperate situation. The Colonel was in the same situation, only worsehe had the whole troop to think of; he ought to be worrying about keeping the men from starving, not on replacing his big Irish dog.

They rode all night; they had no water at all. They didn’t ride fast, but they rode steadily. When dawn flamed up, along the great horizon to the east, they stopped to rest. Bigfoot offered the two of them slices of buffalo tongue. Call ate several bites, but Gus declined, in favor of horse meat.

“I can’t reconcile myself to eating a tongue,” he said. “My ma would not approve. She raised me to be careful about what foods I stuff in my mouth.”

Call wondered briefly what his own mother had been likehe had only one cloudy memory of her, sitting on the seat of a wagon;in fact, he was not even sure that the woman he remembered had been his mother. The woman might have been his auntin any case, his mother had given him no instruction in the matter of food.

During the day’s long, slow ride, the pangs of hunger were soon rendered insignificant beside the pangs of thirst. They had had no water for a day and a half. Bigfoot told them that if they found no water by the next morning, they would have to kill a horse and drink what was in its bladder. He instructed them to cut small strips of leather from their saddle strings and chew on them, to produce saliva flow. It was a stratagem that worked for awhile. As they chewed the leather, they felt less thirsty. But the trick had a limit. By evening, their saliva had long since dried up. Their tongues were so swollen it had become hard to close their lips. One of the worst elements of the agony of thirst was the thought of all the water they had wasted during the days of rain and times of plenty.

“I’d give three months wages to be crossing the Brazos right now,” Gus said. “I expect I could drink about half of it.”

“Would you give up the gal in the general store for a drink?” Bigfoot asked. “Now that’s the test.”

He winked at Call when he said it.

“I could drink half a river,” Gus repeated. He thought the question about Clara impertinent under the circumstances, and did not intend to answer it. If he starved to death he intended, at least, to spend his last thoughts on Clara.

The next morning, the sorrel horse that Gus and Call had both been riding refused to move. The sorrel’s eyes were wide and strange, and he did not respond either to blows or to commands.

“No use to kick him or yell at him, he’s done for,” Bigfoot said, walking up to the horse. Before Gus or Call could so much as blink, he drew his pistol and shot the horse. The sorrel dropped, and before he had stopped twitching Bigfoot had his knife out, working to remove the bladder. He worked carefully, so as not to nick it, and soon lifted it out, a pale sac with a little liquid in it.

“I won’t drink that,” Gus said, at once. The mere sight of the pale, slimy bladder caused his stomach to feel uneasy.

“It’s the only liquid we got,” Bigfoot reminded him. “We’ll all die if we don’t drink it.”

He lifted up the bladder carefully, and drank from it as he would from a wineskin. Call took it next, hesitating a moment beforeputting it to his mouth. He knew he wouldn’t survive another waterless day. His swollen tongue was raw, from scraping against his teeth. Quickly he shut his eyes, and swallowed a few mouthfuls. The urine had more smell than taste. Once he judged he had had his share, he handed the bladder to Gus.

Gus took it, but, after a moment, shook his head.

“You have to drink it,” Call told him. “Just drink three swallows that might be enough to save you. If you die I can’t bury you I’m too weak.”

Gus shook his head again. Then, abruptly, his need for moisture overcame his revulsion, and he drank three swallows. He did not want to be left unburied on such a prairie. The coyotes and buzzards would be along, not to mention badgers and other varmints. Thinking about it proved worse than doing it. Soon they went on, Bigfoot astride the one remaining horse.

That afternoon they came to a tiny waterhole, so small that Bigfoot could have stepped across it, or could have had there not been a dead mule in the puddle. They all recognized the mule, too. Black Sam had had an affection for itin the early days of the expedition, he had sometimes fed it carrots. It had been stolen by the Comanches, the night of the first raid.

“Why, that’s John,” Gus said. “Wasn’t that what Black Sam called him?”

John had two arrows in himboth were feathered with prairie-chicken feathers, the arrows of Buffalo Hump.

“He led it here and killed it,” Bigfoot said. “He didn’t want us to drink this muddy water.”

“He didn’t want us to drink at all,” Call said, looking at the arrows.

“I’ll drink this water anyway,” Gus said, but Bigfoot held him back.

“Don’t,” he said. “That horse piss was clean, compared to this water. Let’s go.”

That night, they had no appetiteeven a bite was more than any of them could choke down. Gus pulled out some rancid horse meat, looked at it, and threw it away, an action Bigfoot was quick to criticize.

“Go pick it up,” he said. “It might rain tonightI’ve been smelling moisture and my smeller don’t often fail me. If we could get a little liquid in us, that horse meat might taste mighty good.“About midnight they heard thunder, and began to see flashes of lightning, far to the west. Gus was immediately joyfulhe saw the drought had broken. Call was more careful. It wasn’t raining, and the thunder was miles away. It might rain somewhere on the plain but would it rain where they were? And would any water pool up, so they could drink it?

“Boys, we’re saved,” Bigfoot said, watching the distant lightning.

“I may be saved, but I’m still thirsty,” Gus said. “I can’t drink rain that’s raining miles away.”

“It’s coming our direction, boys,” Bigfoot saidhe was wildly excited. Privately, he had given the three of them up for lost, though he hadn’t said as much to the young Rangers.

“If the rain don’t come to us, I’ll go to the rain,” Call said.

Soon they could smell the rain. It began to cool the hot air. They were so thirsty it was all they could do to keep from racing to meet the storm, although they had nothing to race on except one tired horse and their feet.

Bigfoot had been right: the rain came. The only thing they had to catch it in was their hatsthe hats weren’t fully watertight, but they caught enough rainwater to allow the starving men to quench their thirst.

“Just wet your lips, don’t gulp ityou’ll get sick if you do,” Bigfoot said.

The lightning began to come closer. Soon it was striking within a hundred yards of where they were huddled; then fifty yards. Call had never been much afraid of lightning, but as bolt after bolt split the sky he began to wonder if he was too exposed.

“Let’s get under the saddle,” Gus said. Lightning spooked him. He had heard that a lightning bolt had split a man in two and cooked both parts before the body even fell to the ground. He did not want to get split in two, or cooked either. But he was not sure how to avoid it, out on the bare plain. He sat very still, hoping the lightning would move on and not scorch anybody.

Then a bolt seemed to hit almost right on Bigfoot. He wasn’t hit, but he screamed anywayscreamed, and clasped his hands over his eyes.

“Oh, Lord,” he yelled, into the darkness. “I looked at it from too close. It burnt my eyes, and now I’m blind.

“Oh Lord, blind, my eyes are scorched,” Bigfoot screamed. Call and Gus waited for another lightning bolt to show them Bigfoot. When it came, they just glimpsed ithe was wandering on the prairie, holding both hands over his eyes. Again, as darkness came back, he screamed like an animal.

“Keep your eyes shutdon’t look at the lightning,” Call said. “Bigfoot’s blindthat’s trouble enough.”

“Maybe he won’t be blind too long,” Gus said. With their scout blinded, what chance did they have of finding their way to someplace in New Mexico where there were people? He thoroughly regretted his impulsive decision to leave with the expedition. Why hadn’t he just stayed with Clara Forsythe and worked in the general store?

Bigfoot screamed againhe was getting farther and farther away. Dark as it was, once the storm passed, they would have no way to follow him, except by his screams. Call thought of yelling at him, to tell him to sit down and wait for them, but if the man’s eyes were scorched, he wouldn’t listen.

“At least it’s washing this dern blood off me,” Gus said. Having to wear clothes encrusted with buffalo blood had been a heavy ordeal.

For a few minutes, the lightning seemed to grow even more intense. Call and Gus sat still, with their eyes tight shut, waiting for the storm to diminish. Some flashes were so strong and so close that the brightness shone through their clamped eyelids, like a lantern through a thin cloth.

Even after the storm moved east and the lightning and thunder diminished, Call and Gus didn’t move for awhile. The sound had been as heavy as the lightning had been bright. Call felt stunned he knew he ought to be looking for Bigfoot, but he wasn’t quick to move.

“I wonder where the horse went?” Gus asked. “He was right here when all this started, but now I don’t see him.”

“Of course you don’t see him; it’s dark,” Call reminded him. “I expect we can locate him in the morning. We’ll need him for Bigfoot, if he’s still blind.”

Call yelled three or four times, hoping to get a sense of Bigfoot’s position, but the scout didn’t answer.

“You try, you’ve got a louder voice,” Call said. Gus’s ability to make himself heard over any din was well known among the Rangers.

But Gus’s loudest yell brought the same result: silence.

“Can you die from getting your eyes scorched?” Gus asked.

The same thought had occurred to Call. The lightning storm had been beyond anything in his experience. The shocks of thunder and lightning had seemed to shake the earth. Once or twice, he thought his heart might stop, just from the shock of the storm. What if it had happened to Bigfoot? He might be lying dead, somewhere on the plain.

“I hope he ain’t dead,” Gus said. “If he’s dead, we’re in a pickle.”

“He could have just kept walking,” Call said. “We know the settlements are north and west. If we keep going, we’re bound to find the Mexicans sometime.”

“They’ll probably just shoot us,” Gus said.

“Why would they, if it’s just the two of us?” Call asked. “We ain’t an army. We’re nearly out of bullets anyway.”

“They shot a bunch of Texans during the war,” Gus recalled. “Just lined them up and shot them. I heard they made them dig their own graves.”

“I wish we could just go back to Austin,” he added. “Why can’t we? The Colonel don’t even know where we are. He’s probably given up and gone back himself, by now.”

“We’ve only got one horse and a few bullets,” Call reminded him. “We’d never make it back across this plain.”

Gus realized that what Call said was true. He wished Bigfoot was therenot much fazed Bigfoot. He missed the big scout.

“Maybe Bigfoot ain’t dead,” he said.

“I hope he ain’t,” Call said.

BIGFOOT WASN’T DEAD. As the storm was playing out, he lay down and pressed his face into the grass, to protect his eyes. The grass was wetits coolness on his eyelids was some relief. While cooling his eyelids, he went to sleep. In the night he rolled overthe first sunlight on his eyelids brought a searing pain.

Gus and Call were sleeping when they heard loud moans. Bigfoot had wandered about a half a mile from them before lying down.

When they approached him he had his head down, his eyes pressed against his arms.

“It’s like snow blindness, only worse,” he told them. “I been snow blindit’ll go away, in time. Maybe this will, too.”

“I expect it will,” Call said. Bigfoot was so sensitive to light that he had to keep his eyes completely covered.

“You need to make me blinders,” Bigfoot said. “Blindersand the thicker the better. Then put me on the horse.”

Until that moment Call and Gus had both forgotten the horse, which was nowhere in sight.I

“I don’t see that horse,” Gus said. “We might have lost him.”

“One of you go find him,” Bigfoot said. “Otherwise you’ll have to lead me.”

“You go find him,” Call said, to Gus. “I’ll stay with Bigfoot.”

“What if I find the horse and can’t find you two?” Gus asked. The plain was featureless. He knew it to be full of dips and rolls, but once he got a certain distance away, one dip and roll was much like another. He might not be able to find his way back to Call and Bigfoot.

“I’ll go, then,” Call said. “You stay.”

“He won’t be far,” Bigfoot said. “He was too tired to run far.”

That assessment proved correct. Call found the horse only about a mile away, grazing. Call had been painstakingly trying to keep his directionshe didn’t want to lose his companionsand was relieved when he saw the horse so close.

By the time he got back, Gus had made Bigfoot a blindfold out of an old shirt. It took some adjustingthe slightest ray of light on his eyelids made Bigfoot moan. They ate the last of their horse meat, and drank often during the day’s march from the puddles here and there on the prairie. Toward the end of the day, Call shot a goose, floating alone in one such small puddle.

“A goose that’s by itself is probably sick,” Bigfoot said, but they ate the goose anyway. They came to a creek with a few bushes and some small trees around it and were able to make a fire. The smell of the cooking goose made them all so hungry they could not sit stillthey wanted to rip the goose off its spit before it was ready, and yet they also had a great desire to eat cooked food. Bigfoot, who couldn’t see but could certainly smell, asked Gus and Call several times if the bird was almost ready. It was still half raw when they ate it, and yet, to all of them, it tasted better than any bird they had ever eaten. Bigfoot even cracked the bones, to get at the marrow.

“It’s mountain man’s butter,” he said. “Once you get a taste for it you don’t see why people bother to churn. It’s better just to crack a bone.”

“Yeah, but you might not have a bone,” Gus said. “The bone might still be in the animal.”

Bigfoot kept his eyes tightly bandaged, but he no longer moaned so much.

“What will you do if you’re blind from now on, Big?” Gus asked.Call felt curious about the same thing, but did not feel it was appropriate to ask. Bigfoot Wallace had roamed the wilderness all his life; his survival had often depended on keenness of eye. A blind man would not last long, in the wilderness. Bigfoot could scout no more he would have to leave off scouting the troops. It would be a sad change, if it happened.

“Oh, I expect I’ll get over being scorched,” Bigfoot said.

Gus said no more, but the question still hung in the air.

Bigfoot reflected for several minutes, before commenting further.

“If I’m blind, it will be good-bye to the prairies,” he said. “I expect I’d have to move to town and run a whorehouse.”

“Why a whorehouse?” Gus asked.

“Well, I couldn’t see the merchandise, but I could feel it,” Bigfoot said. “Feel it and smell it and poke it.”

“I been in whorehouses when I was too drunk to see much, anyway,” he added. “You don’t have to look to enjoy whores.”

“Speaking of whores, I wonder what they’re like in Santa Fe?” Gus asked. Eating the goose had raised his spirits considerably. He felt sure that the worst was over. He had even argued to Call that the reason the goose had been so easy to shoot was that it was a tame goose that had run off from a nearby farm.

“No, it was a sick goose,” Call insisted. “There wouldn’t be a farm around here. It’s too dry.”

Despite his friend’s skepticism, Gus had begun to look forward to the delights of Santa Fe, one of which would undoubtedly be whores.

“You can’t afford no whore, even if we get there alive,” Bigfoot reminded him.

“I guess I could get a job, until the Colonel shows up,” Gus said. “Then we can rob the Mexicans and have plenty of money.”

“I don’t know if the Colonel will make it,” Bigfoot said. “I expect he’ll starve, or else turn back.”

That night, their horse was stolen. They were such a pitiful trio that no one had thought to stand guard. Eating the goose had put them all in a relaxed mood. The horse, in any case, was a poor one. It had never recovered fully from the wild chase after the buffalo. Its wind was broken; it plodded slowly along, carrying Bigfoot. Still, it had been their only mounttheir only resource in more ways than one. They all knew that they might need to eat it, if they didn’t make the settlements soon now. The goose had been a stroke of luckthere might not be another.

Call had hobbled the horse, to make sure it didn’t graze so far that he would have to risk getting lost by going to look for it in the morning. They called the horse Moonlight, because of his light coat. Before Call slept he heard Moonlight grazing, not far away. It was a reassuring sound; but then he slept. When he woke, the hobbles had been cut and there was no sign of Moonlight. The three of them were alone on the prairie.

“We’ll track ‘em, they probably ain’t far,” Bigfoot said, before he remembered that he was blind. His eyes were paining him less, but he still didn’t dare remove his blinders.

“If he was close enough to steal Moonlight, he could have killed me,” Call said. The stealth Indians possessed continued to surprise him. He was a light sleeper; the least thing woke him. But the horse thief had repeatedly come within a few steps of him, yet he had had no inkling that anyone was near.

“Dern, it’s a pity you boys don’t know how to track,” Bigfoot said. “I expect it was Kicking Wolf. That old hump man wouldn’t follow us this far, not for one horse. Kicking Wolf is more persistent.”

“Too damn persistent,” Gus said. He was affronted. Time and again, the red man had bested them.

“All they’ve done is beat us,” he added. “It’s time we beat them at something.”

“Well, we can beat them at starving to death,” Bigfoot said. “I don’t know much else we can beat them at.”

“Why didn’t they kill us?” Call asked.

“I doubt there was more than one of themI expect it was just Kicking Wolf,” Bigfoot said. “Stealing horses is quiet work, but killing men ain’t. He might have woke one of us up and one of us might have got him.”

“It’s a long way to come for one damn horse,” Gus commented. He still stung, from the embarrassment of being so easily robbed.

“Kicking Wolf is horse crazy, like you’re whore crazy. You’d go anywhere for a whore, and he’d go anywhere for a horse.”

“I don’t know if I’d go halfway across a damn desert, for a whore,” Gus said. “I sure wouldn’t for a worn-out horse like Moonlight. Kicking Wolf is crazier than me.

“Bigfoot looked amused. “There’s no law saying an Indian can’t be crazier than a white man,” he said.

All that day, and for the next two, Call and Gus took turns leading Bigfoot. It was tiring work. Bigfoot had a long stride, longer even than Gus’sthe two of them had almost to trot, to keep ahead of him. Then, too, the prairie was full of cracks and little gullies. They had to be alert to keep him on level groundit annoyed him to stumble. It stormed again the second night, though with less lightning. Water puddled here and there; they were not thirsty, but once they finished the last few bites of horse meat, they had no food. Call was afraid to roam too far to hunt, for fear of losing Gus and Bigfoot. In any case they saw no game, except a solitary antelope. The antelope was in sight for several hoursGus thought it was only about three miles away, but Call thought it might be farther. In the thin air, distances were hard to judge.

Bigfoot considered it peculiar that the antelope stayed in sight so long. Not to be able to use his own eyes was frustrating.

“If I could just have one look, I could give an opinion,” he said. “It might not even be an anteloperemember them mountain goats that turned into Comanches?”

Reminded, Gus and Call gave the distant animal their best scrutiny. Gus was of the opinion that the animal might be a Comanche, but Call was convinced it was just a plain antelope.

“Go stalk it, then,” Bigfoot said. “We’ll sit down and wait. A little antelope rump would be mighty tasty.”

“Let Gus stalk it,” Call said. “He’s got better eyes. I’ll wait with you.”

Gus didn’t relish the assignment. If the antelope turned out to be a Comanche, he would be in trouble. He was hungry, though, and so were the others.

“Don’t shoot until you’ve got a close shot,” Bigfoot said. “If you can’t hit the heart, shoot for the shoulder. That’ll slow him down enough that we can catch him.”

Gus stalked the antelope for three hours. The last three hundred yards, he edged on his belly. The antelope lifted its head from time to time, but mostly kept grazing. Gus got closer and closerhe remembered that he had missed the first antelope, at almost point-blank range. He wanted to get very closeit would do his pride good to bring home some meat, and his belly would appreciate it, too.

He got to within two hundred yards, but decided to edge a little closer. He thought he might hit it at one hundred and fifty yards. He kept his head down, so as not to show the animal his face. Bigfoot had informed him that prairie animals were particularly alarmed by white faces. Indians could get close enough to kill them because their faces weren’t white. He kept his hat low, and his face low, too. When he judged he was within about the right distance, he risked a peek and to his dismay saw no antelope. He lookedthen stood up and lookedbut the antelope was gone. Gus ran toward where it had been standing, thinking the animal would have lain downthen he glimpsed it running, far to the north, farther than it had been when they first noticed it. Following it would be pointless; for a moment, stumbling around after the antelope, he felt a panic take him. He could not be sure which direction he had come from. He might not even be able to find Bigfoot and Call. Then he remembered a rock that stuck up a little from the ground. He had passed it in his crawl. He walked in a half circle until he saw the rock and was soon back on the right course.

Even so, he was disgusted when he got back to his companions.

“I wasted all that time,” he said. “He took off and ran. Let’s just hurry up and get to New Mexico.”

“Oh, we’re in New Mexico,” Bigfoot said. “We just ain’t in the right part of it, yet. My eyes are improving, at least. Pretty soon I won’t have to be led.”

Bigfoot’s eyes did improve, even as their bellies grew emptier. On the third day after the storm, he was able to take his blinders off in the late afternoon. Soon afterward, he found a small patch of wild onions and dug out enough for them to have a few each to nibble. It wasn’t much, but it was something.

The next morning, waking early, Gus saw the mountains. At first, he thought the shapes far to the north might be cloudsstorm clouds. Once the sun was well up, he saw that the shapes were mountains. Call saw them, too. Bigfoot still had to be careful of his eyes in full lighthe wanted to look, but had to give up.

“If it’s the mountains, then we’re saved, boys,” he said. “There’s got to be people between here and the hills.“They walked all day, though, without foodthe mountains seemed none the less distant.

“What if we ain’t saved?” Gus whispered to Call. “I’m hungry enough to eat tongue, or bugs, or anything I can catch. Them mountains could be fifty miles away, for all we know. I ain’t gonna last no fifty milesnot unless I get food.”

“I guess you’ll last if you have to,” Call told him. “Bigfoot says we’ll come to villages before we get to the hills. Maybe it will only be twenty milesor thirty.”

“I could eat my belt,” Gus said. He actually cut a small slice off his belt and ate it, or at least chewed it and swallowed it. The result didn’t please him, though. The little slice of leather did nothing to relieve his hunger pangs.

They walked steadily all day, toward the high mountains. They ignored their stomachs as best they couldbut there were moments when Call thought Gus might be right. They might starve before they reached the villages. Bigfoot had taken a fever somehow most of the day he stumbled along, delirious; he seemed to think he was talking to James Bowie, the gallant fighter who had died at the Alamo.

“We ain’t him, we’re just us,” Gus told him several times, but Bigfoot kept on talking to James Bowie.

Toward the evening of that day, as the shadows from the mountains stretched across the plain, Gus thought he saw something encouraginga thin column of smoke, rising into the shadows. He looked again, and again he saw smoke.

“It’s from a chimney,” he said. “There’s a house with a chimney up there somewhere.”

Gus saw the smoke, too, and Bigfoot claimed he smelled it.

“That’s wood smoke, all right,” he said. “I reckon it’s pinon. They use pinon for fires, out here in New Mexico.”

They hurried for three miles and still weren’t to the village. Just as they were about to get discouraged again, they came over a little rise in the ground and saw forty or fifty sheep, grazing on the plain ahead. A dog began to barktwo sheepherders, just making their campfire, looked up and saw them. The sheepherders were unarmed and took fright at the sight of the three Rangers.

“I expect they think we’re devils,” Bigfoot said, as the two sheepherders hurried off toward a village, a mile or two away. The sheep they left in care of the two large dogs, both of whom were barking and snarling at the Texans.

“They didn’t need to runI’m just glad to be here,” Gus said. In fact, he was so moved by the sight of the distant houses that he felt he might weep. Crossing the prairie he had often wondered if he would ever see a house again, or sleep in one, or ever be among people again at all. The empty spaces had given him a longing for normal thingswomen cooking, children chasing one another, blacksmiths shoeing horses, men drinking in bars. Several times on the journey, he had thought such things were lost foreverthat he would never get across the plain to sit at a woman’s table again. But now he had.