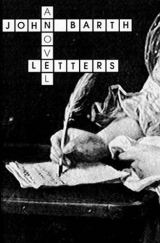

Текст книги "Letters"

Автор книги: John Barth

Жанр:

Современная проза

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 19 (всего у книги 75 страниц)

~ ~ ~

S: The Author to Todd Andrews. Soliciting the latter’s cooperation as a character in a new work of fiction.

Department of English, Annex B

State University of New York at Buffalo

Buffalo, New York 14214

March 30, 1969

Mr. Todd Andrews

Andrews, Bishop, & Andrews, Attorneys

Court Lane

Cambridge, Maryland 21613

Dear Mr. Andrews:

Some fifteen years ago, when I was 24 and 25 (Eisenhower! Hurricane Hazel!), I wrote my first published novel, a little tidewater comedy called The Floating Opera. It involved, among other things, a showboat remembered from Aubrey Bodine’s photographs and an imaginary 54-year-old Maryland lawyer named Todd Andrews, who once in 1937, when he was 37, cheerfully attempted to blow himself up together with the Floating Opera and a goodly number of his fellow Eastern Shorers. You may have heard of the story.

At that time, as a budding irrealist, I took seriously the traditional publisher’s disclaimer—“Any resemblance between characters in this novel and actual persons living or dead,” etc. – and would have been appalled at the suggestion that any of my fictive folk were even loosely “drawn from life”: a phrase that still suggests to me some barbarous form of capital punishment. I wanted no models in the real world to hobble my imagination. If, as the Kabbalists supposed, God was an Author and the world his book, I criticized Him for mundane realism. Had it been intimated to me that there actually dwelt, in the “Dorset Hotel,” a middle-aged bachelor lawyer with subacute bacterial endocarditis, who rented his room by the day and spent his evenings at an endless inquiry into his father’s suicide…

No matter. Life is a shameless playwright (so are some playwrights) who lays on coincidence with a trowel. I am about the same age now as “Todd Andrews” was when he concluded that he’d go on living because there’s no more reason to commit suicide than not to: I approach reality these days with more respect, if only because I find it less realistic and more mysterious than I’d supposed. I blush to confess that my current fictive project, still tentative, looks to be that hoariest of early realist creatures, an epistolary novel – set, moreover and by God, in “Cambridge, Maryland,” among other more or less actual places, and involving (Muse forgive me) those most equivocal of ghosts: Characters from the Author’s Earlier Fictions.

There, I’ve said it, and quickly now before I lose my nerve, will you consent, sir, to my using your name and circumstances and what-all in this new novel, clearing the text of course with you before its publication et cetera and for that matter (since other “actual persons living or dead” may wander through this literary mail room) to my retaining you, at your customary fee, for counsel in the libel way?

Cordially,

P.S.: Do you happen to know a Lady Germaine Amherst (Germaine Lady Amherst? Germaine Pitt Lady Amherst? Lady Germaine Pitt-Amherst?)? What about a nut in Lily Dale, N.Y., named Jerome Bonaparte Bray, who believes himself to be the rightful king of France, myself to be an arrant plagiarist, and yourself to be his attorney?

H: The Author to Todd Andrews. Accepting the latter’s demurrer.

Department of English, Annex B

State University of New York at Buffalo

Buffalo, New York 14214

Sunday, April 6, 1969

Todd Andrews

Andrews, Bishop, & Andrews, Attorneys

Court Lane

Cambridge, Maryland 21613

Dear Mr. Andrews:

How a letter written and presumably mailed by you in Cambridge on Good Friday could reach my office here in Buffalo on Holy Saturday is a mystery, considering the usual decorous pace of the U.S. mail. But on this pleasant Easter Sunday afternoon, having got through the Times betimes, I strolled up to the campus to check out some epistolary fiction from the library, found it closed for the holiday, stopped by my office, and voila: its postmark faint to the point of illegibility; its twin 6¢ FDR’s apparently uncanceled; the mystery of its delivery intact.

And its plenteous contents avidly received, sir, twice read already, and respectfully perpended. Be assured that I share your reservations; nevertheless, I forge away.

Be assured further that I will honor your request not to make use of your name and situation, or the confidences you share with me in your letter, without your consent. When I have a view of things at all, it is just your sort of tragic view – of history, of civilizations and institutions, of personal destinies – and I hope I live it out with similar scruple. Even given your eventual consent (which I still solicit), I would of course alter facts as radically as necessary for my purposes, as I did fifteen years ago when I invented a 54-year-old lawyer named Todd Andrews, and cut the Macks from whole cloth to keep him company. The boundary between fact and fiction, or life and art, if it is as arguable as a fine legal distinction, is as valuable: hard cases make good law.

So we are, I think, in the accord your letter would bring us to, except for one small matter of record. You wonder why I made no mention of our conversation in the Cambridge Yacht Club on New Year’s Eve, 1954. It is because I don’t recall being there, though I acknowledge that something like your Inquiry and Letter must have turned my original minstrel-show project into the Floating Opera novel. In the same spirit, I here acknowledge in advance your contribution, intended or inadvertent, to the current project: it had not occurred to me to reorchestrate previous stories of mine in this LETTERS novel, only to have certain of their characters stroll through its epistles. But your ironic mention of sequels tempts me to that fallible genre, and suggests to me that it can be managed without the tiresome prerequisite of one’s knowing the earlier books. I will surely hazard it: not perversely, to see whether it can be got away with, but because it suits my Thematic Purposes, as we say.

For this contribution, thanks. Let’s not press further the historicity of our “encounter.” Given your obvious literary sophistication, you will agree with me that a Pirandelloish or Gide-like debate between Author and Characters were as regressive, at least quaint, at this hour of the world, as naive literary realism: a Middle-Modernist affectation, as dated now as Bauhaus design.

Finally, my thanks for your expression of goodwill and loyalty to our medium. To be a novelist in 1969 is, I agree, a bit like being in the passenger-railway business in the age of the jumbo jet: our dilapidated rolling stock creaks over the weed-grown right-of-ways, carrying four winos, six Viet Nam draftees, three black welfare families, two nuns, and one incorrigible railroad buff, ever less conveniently, between the crumbling Art Deco cathedrals where once paused the gleaming Twentieth Century Limited. Like that railroad buff, we deplore the shallow “attractions” of the media that have supplanted us, even while we endeavor, necessarily and to our cost, to accommodate to that ruinous competition by reducing even further our own amenities: fewer runs, fewer stops, fewer passengers, higher fares. Yet we grind on, tears and cinders in our eyes, hoping against hope that history will turn our way again.

In the meanwhile, heartening it is to find among the dross a comrade, a fellow traveler, whose good wishes we reciprocate most

Cordially,

P.S.: As to those cinematographical rumors. The film rights to The Floating Opera are contracted, and a screenplay is in the works, but I have no particular confidence that the story will actually be filmed, on location or elsewhere. Many shuffle the cards who do not play when the chips are down.

In any case, the Prinz-Mensch project is something different, I gather, and altogether more ad libitum. Prinz I know only by his semisubterranean reputation on the campuses; in 1967 he communicated to me, indirectly and enigmatically (he will not write letters; is said to be an enemy of the written word) his interest in filming my “last novel,” which at the time was Giles Goat-Boy. Later he introduced himself to me by telephone and, as best I could infer, gave me to know that it was my “last book” he was interested in filming—i.e., by that time, the series Lost in the Funhouse, just published. I had supposed that book not filmable, inasmuch as the stories in it were written for print, tape, and live voice, have no very obvious continuity, and depend for their sense largely on manipulations of narrative viewpoint which can’t be suggested visually. I told Prinz these things. If I read correctly his sighs, grunts, and hums, they were precisely what appealed to him!

I let him have an option, the more readily when he intimated that our friend Ambrose Mensch might do the screenplay. Our contract stipulates that disagreements about the script are to be settled by a vote among the three of us; so far I’ve found Prinz at once so antiverbal and so personally persuasive that I’ve seconded, out of some attraction to opposites, his rejection of Mensch’s trial drafts. And almost to my own surprise I find myself agreeing to his most outrageous, even alarming notions: e.g., that by “last book” he means at least a kind of Ongoing Latest (he wants to “anticipate” not only the work in progress since Funhouse but even such projected works as LETTERS!); at most something ominously terminal.

No question but he will execute a film: my understanding is that principal photography is about to be commenced, both down your way and – for reasons that we merely literate cannot surmise – up here along the Niagara Frontier as well. I find myself trusting him rather as a condemned man must trust his executioner.

We shall, literally, see.

I: The Author to Lady Amherst. Accepting her rejection of his counterinvitation.

Department of English, Annex B

SUNY/Buffalo

Buffalo, New York 14214

April 13, 1969

Professor Germaine G. Pitt, Lady Amherst

Office of the Provost, Faculty of Letters

Marshyhope State University

Redmans Neck, Maryland 21612

My dear Lady Amherst:

In response to your note of April 5: I accept, regretfully, your vigorous rejection of my proposal, and apologize for any affront it may have given you. I did not mean – but never mind what I did not mean. I accede to the counsel of your countryman Evelyn Waugh: Never apologize; never explain.

May I trust, all the same, that you will not take personally my use of at least the general conceit – for the principal character in an epistolary novel as yet but tentatively titled and outlined – of A Lady No Longer in Her First Youth, to represent Letters in the belletristic sense of that word?

Cordially,

M: The Author to Lady Amherst. Crossed in the mails. Gratefully accepting her change of mind.

Chautauqua Lake, New York

April 20, 1969

Germaine G. Pitt

24 L Street

Dorset Heights, Maryland

My dear Ms. Pitt,

My note to you of April 13, accepting your rejection of my proposal, must have crossed in the mails yours to me of April 12, tentatively withdrawing that rejection: a letter my pleasure in the receipt of which, as that old cheater Thackeray would write, “words cannot describe.” Since, like myself, you seem given to addressing certain correspondents on certain days of the week, I happily imagine that this letter, too – welcoming your reconsideration and hoping that you will entrust me with whatever confidences you see fit to share – will have passed, somewhere between western New York and the Eastern Shore of Maryland (along the Allegheny ridges, say: the old boundary between British and French America), yet another from you, bringing to light those mysteries with which yours of the 12th is big.

Vicissitudes! Lovers! Pills! Radical corners turned! The old familiar self no longer recognizable! Encore!

I jest, ma’am, but sympathetically. (Excuse my longhand; I write this from a summer cottage at Chautauqua, where snow fell only yesterday into the just-thawed lake. And on the Chesapeake they are sailing already!) If April – in the North Temperate Zone, at least – is the month of suicides and sinkings, that’s because it’s even more the month of rebeginnings: Chaucer’s April, the live and stirring root of Eliot’s irony. (So you really knew Old Possum! How closely, please? You are not the One who settles a pillow by her head and says to Prufrock: “That is not what I meant at all. That is not it, at all…”?!) In this latter April spirit I wish you a happy birthday.

I also swear by all the muses that I am not just now nor have I lately been in touch with Ambrose M. We have amicably drifted apart in recent years, both personally and aesthetically; have not corresponded since early in this decade. The news of his connection with Reg Prinz was news to me. I’ve seen (and concurred with Prinz in the rejection of) A’s first draft of the opening of that screenplay alleged to be based on some story of mine. It seems tacitly understood between us that direct communication would be counterproductive while he’s taking – with my tacit general approval – vast liberties with my fiction. Have you and he become close?

Enfin: I am by temperament a fabricator, not a drawer-from-life. I know what I’m about, but shall be relieved to get home to wholesale invention, much more my cup of tea. Meanwhile, I urge you to tell on, while I like a priest in the box draw between us now a screen. Or better, like a tape recorder, not distract you by replying. Or best, like Echo in the myth, give you back eventually your own words in another voice.

Cordially. Hopefully. Exhortingly. Expectantly.

Respectfully. Sincerely,

– L Street? I find neither in my memory nor on my map of Cambridge any neighborhood or suburb called Dorset Heights, or streets named for letters of the alphabet.?

3

~ ~ ~

T: Lady Amherst to the Author. The Third Stage of her affair with Ambrose Mensch. Her latter-day relations with André Castine.

24 L Street

Dorset Heights, Maryland 21612

Saturday, 3 May 1969

My dear B. (or, Dear Diary),

Thanks, I think, for not responding to my last two “chapters.” You understand why, even as I made to slip last Saturday’s into the drop box (such odd-shaped ones over here!), it occurred to me to post it on the Monday by certified mail instead: having seen fit to comply with your request, I need only some confirmation that these letters are being received, and by the addressee. Your “John Hancock” on the receipt is my “Go now and sin some more.”

I should prefer not to. I am not heartily sorry—au contraire—but I am heartily weary of things sexual. By Ambrose’s count (leave it to him) he had as of April’s end ejaculated into one or another of His Ladyship’s receptacles no fewer than 87 several times since the month – and the “Second Stage” of our love affair – began. More precisely, since the full Pink Moon of 2 April, when the onset of my menses so roused him that I had to take it by every detour till the main port of entry was clear (A’s analogy, tricked out with allusions to American runners of the British blockade in “our” wars of 1776 and 1812). Which comes, he duly reported two days ago, to three comes per diem.

Thank God then it was Thursday, I replied, and April done, for my whole poor carcase was a-crying Mayday. The cramps were on me again, breasts tender, ankles swollen, I was cross and weepy: all signs were (he’d be glad to know) that douche and cream and pessary had withstood his “low-motile swimmers.”

As if I’d spoken by chance some magic phrase, my lover’s humour changed entirely. He removed his hand, rezipped his fly, asked me gravely, even tenderly, was I quite sure? I was, despite the irregular regularity of it: by next night’s full moon – which he told me was the Flower Moon – his overblown blossom would close her petals for a spot of much needed rest. He kissed me then like (no other way to say it) a husband, and left my office, where, not long before, our committee had delighted John Schott by proposing after all, alas, A. B. Cook for the Litt.D. (We could delay no longer. What’s more – but I shall return to this. Would you had said yes! Failing that, would it could be Ambrose!) That day, like a played-out Paolo and Francesca, we made love no more, just read books.

Yesterday too. Sweet relief! A. stopped by early; let himself through the front door of 24 L before I was up, as he sometimes does. I took for granted it was the usual A.M. quickie, as he calls it, and as I had indeed begun flowing that night like a little Niagara, I rolled over with a sigh to let him in the back door and begone. But lo, he was all gentle husband again: had only stopped to ask could he fetch me a Midol? Make tea? He jolly could, and jolly did. I was astonished, mistrustful. Some new circus trick in the offing? Or l’Abruzzesa… No, no, he chided: merely in order to have “run in a month’s glissando the whole keyboard of desire” (his trope), he hoped we might add one last, 88th connexion to the score we’d totted up between Pink and Flower Moons; but he vowed he was as pleasantly spent as I by our ardent April, and would be pleased to shake less roughly, and less often, his darling bud in May.

So I blew him, whilst our Twining’s Earl Grey was a-cooling. He even tasted different: something has changed! Last evening we made sea trout au cognac together, spent the P.M. (a longie) with books and telly; then we slept together, like (quoth he, after Donne) “two-sevenths of the snorting Sleepers in their Caves.” Slept, sir, so soundly that Yosemite’s Tunnel Sequoia, which I read this morning fell last night, could have dropped on 24 L and never waked us. Now he’s back to his strange screenplay; I to my novel-of-yours-of-the-month. Our “2nd Stage,” it would appear, is over; not without some apprehension I approach the 3rd, whatever in the world it may prove to be. Meanwhile, I read and bleed contently – and am informed by my tuckered lover that, this being the Saturday before the first Sunday in May, phials of the blood of martyred St. Januarius in the reliquary of the Naples duomo are bubbling and bleeding too. Tutti saluti!

The book I’m into, and look to be for some while yet, is, per program, your Sot-Weed Factor. But how am I to bring, to the enterprise of reading it, any critical detachment, when I am busy being altogether dismayed by the Cooke-Burlingame connexion and the Laureate of Maryland business in your plot? Ambrose and the meagre Marshyhope library have confirmed the existence of an historical Ebenezer Cooke in the 17th and 18th Centuries, his ambiguous claim to laureateship, and his moderately amusing Sot-Weed Factor poem from which your story takes off. And Cook Point on the Choptank, of course, is not far from Redmans Neck. But John (if I may now so call you?): what am I to do with these “coincidences” of history and your fiction with the facts of my life, which beset, besiege, beleaguer me in May like Ambrose’s copious sperm in April? Never mind such low-motile hazards as my opening your novel at random to find a character swearing by “St. Januarius’s bubbling blood”: I quite expect to meet Ambrose himself on some future page of yours; perhaps even (like Aeneas finding his own face in Dido’s frescoes of the Trojan War) Yours Truly bent over the provostial desk with him in flagrante delicto…

No more games! You know, then, of an original “Monsieur Casteene,” Henry Burlingame, and Ebenezer Cooke: what I must know is their connexion, if any, with “my” André, and with those nebulous name-changers at Castines Hundred in Ontario, and with that alarming Annapolitan to whom we’re surrendering our doctorate of letters. Not to mention… my son! I have chosen to trust you as an author; I do not know you as a man. But I know (so far as I know) that I am real, and I beseech you not to play tired Modernist tricks with real (and equally tired) people. If you know where André Castine is, or anything about him, for God’s sake tell me! If A. B. Cook and his “son” Henry Burlingame VII are pseudonymous mimics of your (or History’s) originals, tell me! I believe “our” Cook to be dangerous, as you know. Am I mistaken? What do you know?

I feel a fool, sir, and I dislike that not unfamiliar feeling. It isn’t menstruation makes me cross, but being crossed and double-crossed.

Damn all of you!

By which pronoun I mean, momentarily I presume, you men. Not included in last Saturday’s roster of my former beaux was the one woman I’ve ever loved, my “Juliette Récamier”—a French New Novelist in Toronto whose meticulous unsentimentality I found refreshing after Hesse and my British lovers – and before it was revealed to be no more than increasingly perverse and sterile rigour. Yet I recall warmly our hours together and rather imagine that, had she not long since abjured the rendering of characters in fiction, she alone of my writer-friends might have got me both sympathetically and truly upon the page, with honour to both life and literature, love and art. Lesbian connexions have not appealed to me before or since: I mention my “Juliette” for the sake of completeness, and at the risk of your misconstruing her (as Ambrose does) into allegory. It is men I love, for better or worse, when I love; and of all men André, when he sees to it that our paths cross.

I think I pity the man or woman whose experience does not include one such as he: one to whom it is our fate and hard pleasure to surrender quite. We are not the same in our several relationships; different intimacies bring out different colours in us. With Jeffrey (and Hermann, and Aldous, and Evelyn, and the rest, even “Juliette”) I was ever my own woman; am decidedly so even with Ambrose, except that the lust we roused in each other last month truly lorded it over both of us. To André alone I surrendered myself, without scruple or consideration, almost to my own surprise, and “for keeps.” Nothing emblematic, romantic, or sex-determined about it; I have known men similarly helpless, to their dismay, in some particular connexion. It is an accident of two chemistries and histories; while my rational-liberal-antisentimental temperament deplores the idea as romantic nonsense, there’s no dismissing the fact, and any psychological explanation of it would be of merely academic interest.

Toronto: I spent the summer and fall of 1966 there, lecturing at the university, consoling myself with “Juliette” (their novelist in residence) for the loss of my husband, and waiting in vain, with the obvious mixture of emotions, for some word from André, who I assumed had arranged my lectureship. November arrived, unbelievably, without a sign from him. On the 5th, a Saturday, unable to deal with the suspense, I drove out to Stratford with my friend to see a postseason Macbeth at the Shakespeare Festival Theatre. Between Acts III and IV as I stepped into the lobby for intermission, I was handed a sealed envelope with my name on it by one of the ushers. I was obliged to sit before I could open it. The note inside, in a handwriting I knew, read: “My darling: Dinner 8 P.M., Wolpert Hotel, Kitchener.”

No signature. That little town, as you may know, is along the dreary way from Stratford to Toronto. I have no memory of the rest of the play, or of the ride back. My friend (who like Juliette Récamier had the gift of inferring much from little, and accurately, in matters of the heart) kindly drove me to that surprising, very European old hotel in the middle of nowhere, tisking her tongue at my submissiveness but declaring herself enchanted all the same by the melodrama. She waited in the lobby whilst I went up the stairs, literally trembling, to (what I’ve learned since to be) the improbably elegant German dining room on the second floor. The hostess greeted me by name. I saw him enter, smiling, from across the room, unmistakably my André: handsomer at fifty than he’d been as a young man! My heart was gone; likewise my voice, and with it my hundred questions, my demands for explanation.

“Your friend has been informed. She understands,” he assured me in Canadian French, as he helped me into a chair – none too soon, for the sound of that richest, most masculine of voices, the dear dialect I’d first heard in Gertrude Stein’s house, undid my knees. “I urged her to have dinner with us, but she wanted to get back to Toronto. Charming woman. I quite approve.”

I am told we had good veal and better Moselle: André prefers whites with all his meats. I am told that I was not after all too gone in the head to protest the impossibility of our dining and conversing together as if no explanation, no justification were needed. I am told even that I waxed eloquent upon the outrageous supposition that his smile, his touch, the timbre of that voice, made me “his” again despite everything, as in the lyrics of a silly song. Where was our son? I’m told I demanded. What could possibly justify my being quite abandoned but never quite forsaken, my wounds kept always slightly open by those loving, heartless letters? And finally – I am told I asked – how was I to get home that night, when this absurd rendezvous was done and I’d regained my breath and strength?

What I did not question until later, to André’s own professed surprise, was his authenticity. Appearances and mannerisms are easily mimed: did I need no proof, after all those years, that he was he? Well, I didn’t; didn’t care (at the time) even to address so vertiginous a question. If, somewhile later, I began to wonder, it was because for the first time since our parting he had come to me in the role of himself: had he posed as another, I’d never have doubted at all.

We stayed at the Wolpert until Monday, scarcely leaving André’s room except for meals. He was obliged, as I stood about dazed, to undress me himself. When he first entered me – after so many years, so many odd others – I became hysterical. From Kitchener he took me back to Castines Hundred, where I enjoyed something of a nervous collapse. It was as if for twenty-five years I had been holding my breath, or an unnatural pose, and could now “let go,” but had forgot how. It was as if – but I can’t describe what it was as if. Except to say that for André it was as if our quarter-century separation had been a month’s business trip: a regrettable bother, but not uninteresting, and happily done with. Good to be back, and, let’s see, what had we been discussing?

Sedatives helped, prescribed by the Castines’ doctor. Arrangements were made at the university to reschedule my lectures after my recovery. André too, I learned (now Baron Castine since his grandfather’s death), had been briefly married – a mere dozen years or so, as it were to mark time “till my own marriage had run its course”—and had sired “one or two more children,” delightful youngsters, I’d love them, off in boarding schools just then, pity. Had I truly borne no more since ours? Dommage. Now that chap, our Henri, yes: chip off the old block, he: more his grandfather’s son, or his “uncle’s,” than his father’s: at twenty-six a more promising director of the script of History than either of them at his age, busy redoing what he André had spent half a lifetime undoing. Crying shame he wasn’t at Castines Hundred then and there: it was high time we approached the question of revealing to him his actual parentage…

Tranquillisers. And where might the lad be? Ah, he André had hoped against hope that I might have had some word from him: the boy was at the age when certain of his predecessors had revised their opinion of their parents, and was skilful enough to discover them for himself. Last André had heard, Henri was underground in Quebec somewhere, playing Grandpère’s nasty tricks on the Separatists, who took him for their own. So at least he’d given out. Before that he’d been working either with or against the man he understood to be his father, down in Washington. But his track had been lost, just when André much desired to find it. Of this, more when I was stronger, and of his own activities as well: a little bibliography of “historical corners turned” that he was impatient to lay before me, “like the love poems they also are.”

He had of course followed with close interest my own career: he commended my articles on Mme de Staël (whom however he advised me now to put behind) and my patience with my late husband Jeffrey’s later adulteries. He informed me, in case I should be interested, that Jeffrey had been infertile if not quite impotent after the 1940’s, but had honoured paternity claims against him rather than acknowledge his infirmity. My essay on Héloïse’s letters to Peter Abelard, he said, had been heartbreakingly sympathetic, yet dignified and strong as poor Héloïse herself. Had I read any good books lately?

By the beginning of the new year I was, if not exactly recovered (I never shall be), at least “together” enough to return to the university and to “Juliette,” with André’s approval – which I hadn’t sought – and with three other souvenirs, two of which I had sought.

The first was that promised account of his activities since 1941. On that head I am sworn to secrecy; you would not believe me anyroad. But if even a tenth of what he told me is true, André has indeed “made history,” as one might make a poem – and to no other end! Little wonder I have difficulty accepting any document at all, however innocuous, as “naive”: I look for hidden messages in freshman compositions and interoffice memoranda; I can no longer be at ease with the documentary source materials of my own research, which for all I know may be further “love poems” from André. A refreshing way to view Whittaker Chambers’s “pumpkin papers,” or Lee Harvey Oswald’s diary! And both enterprises, I need not add, had kept him away, “for her own protection,” from me as well as from the woman he’d married “as a necessary cover” at that aforementioned turning point in his life. (He’d also been fond of her, he acknowledged, even after “her defection and subsequent demise.” I didn’t ask.)

The second souvenir was the news that our son had been raised to believe himself an orphan, the son of André’s “deceased half brother and sister-in-law!” What’s more, it now turns out (read “was then by him declared”) that he did indeed have a half brother, quite alive, “down in the States”—or half had a brother, or something. “All very complicated,” he admitted: the understatement of the semester. And his “necessary ruse” (for the boy’s own security, don’t you know) bid fair to backfire; for the evidence was that our son had located either this half brother or his semblable, accepted him as his father, and was doing the man’s political work, the very obverse of André’s own.