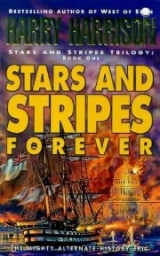

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes Forever"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Соавторы: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 9 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

“A word, sir, if I could,” Harvey Preston said.

Charles Francis Adams looked up from the papers on his desk with irritation, his concentration broken. “Not now, Preston – you can see that I am working.”

“It is about the servants, sir.”

“Well, yes, of course. Best to close the door.”

When Secretary of State Seward had secured for Adams the position of minister to Great Britain it was Abraham Lincoln himself who offered him congratulations. Adams was no stranger to the Presidential Mansion – after all his father had been President – and his grandfather as well. But this had been a very different occasion. Lincoln had introduced him to an Assistant Secretary of the Navy, one Gustavus Fox. For a navy man Fox had a great interest in matters of security. English servants, important papers, state secrets and the like. He had recommended the appointment of Preston, “A former military man” as house manager. Or butler, or major-domo. His exact role remained unclear. Yes, he did indeed manage Adams’s house, keeping an eye on the cook and hiring the servants.

But he did a lot more than that. He knew far more about affairs of state in London, Court gossip, even matters of the military, than Adams himself did. And his information always proved accurate. After a few months Adams began to rely on the facts he assembled, using some of them as the basis of reports to Washington. The reference to servants meant that he had information to reveal.

“Something very important is happening in Whitehall,” Preston said as soon as the door was closed.

“What?”

“I don’t know yet. My informant, who is a junior clerk in one of the departments, would not tell me without payment of a sum of money.”

“Don’t you usually pay for information?”

“Of course – but just a few shillings at a time. This time it is different. He wants twenty guineas, and I don’t have that sum available.”

“That is a lot of money!”

“I agree. But he has never failed me before.”

“What do you suggest?”

“Pay him. We must take the chance.”

Adams thought for a moment, then nodded. “I will get it from the safe. How do you meet him?”

“He comes to the carriage house at a prearranged time.”

“I must be there,” Adams said firmly.

“He must not see you.” Preston chewed his lip in thought. “It could be done. Get there early, sit in the carriage in the dark. I’ll keep him at the door.”

“Let us do it.”

Adams waited in the carriage, growing more and more unsure of his decision. The man was late, the whole thing might be a plot to embarrass him. He was definitely not acquainted with this kind of occasion. His thoughts spinning, he jumped when there was a sudden loud knocking on the door. He pushed back against the seat, trying to get as close as he could without being seen. There was the squeak of rusty hinges.

“Do you ’ave it?” a cockney voice whispered.

“I do – and it had better be worth it.”

“It is, sir – I swear on my mother’s soul. But let me see it first.”

There was the dull clink of gold against gold and the man’s gasp.

“That’s it, yes it is. You must tell your master that there is an uproar in Parliament, the military, everyone. I hear that they may go to the Queen.”

“About what?”

“We’re not supposed to know, but clerks talk. It seems that the American army has invaded Canada, shot up some soldiers there. There is even talk of war.”

“Names, places?”

“I’ll get them, sir. Tomorrow at this time.”

“Then here is half the money. The rest when we have the details.”

The door closed and Adams emerged from the carriage. “Is he speaking the truth?”

“Undoubtedly.”

Adams was at a loss. “This could not happen, the army would not do a thing like that.”

“The British believe that it happened, that is all we have to know.”

Adams started toward the house, turned back. “Find out when the next mail packet sails. We must get a full report of this to the State Department. As soon as we can.”

The emergency meeting of the British Cabinet lasted until late afternoon. There was a constant coming and going between Downing Street and the House of Commons, high-ranking officers, generals and admirals for the most part. When a decision was finally reached the order was passed and Lord Palmerston’s carriage clattered on the cobbles up to the main entrance of the House of Commons. Palmerston was carried out of the building by four strong servants, who lifted him carefully through the carriage door. Not carefully enough for he cried out in pain, then cursed his bearers when his bandaged foot struck against the frame. Lord John Russell climbed in and joined him for the short ride down Whitehall, then along the Mall to Buckingham Palace. Word had been sent ahead of this momentous visit and the Queen was waiting for them when they were ushered into her presence. She was dressed entirely in black, still in mourning for Albert, a period of mourning that would last her lifetime.

Lord Palmerston was eased into a chair. The pain was clear on his face but he struggled against it and spoke.

“Your Majesty. Your cabinet has been assembled this entire day in solemn conference. We have consulted with responsible members of the armed forces before reaching a decision. You will of course have seen the dispatch from Canada?”

“Report?” she said vaguely. Her eyes were misted and red with weeping. Since Albert’s death she had barely been able to function. At times she tried; most of the time she refused to leave her private chambers. Today, with great effort, she had emerged to meet with Palmerston. “Yes, I think that I read it. Very confused.”

“Apologies, ma’am. Written in the heat of action no doubt. If I could elucidate. Our cavalry is thinly stretched along the length of the Canadian border. We have limited troops there so, in order to keep close and continuous watch, it is my understanding that the local militia has been deployed. Commanded by British officers of course. It was one of these patrols that was stationed near the Quebec village of Coaticook that came under attack.”

“My soldiers – attacked!” Her attention was attracted at last. Her voice rose to a shrill screech. “This is a grave matter, Lord Palmerston. Terrible! Terrible!”

“Grave indeed, ma’am. It appears that a road of some sort crosses the border here leading to Derby, in the American state of Vermont. Lord Russell, if I could have the map.”

Russell opened the map on an end table and the servants carried it over and placed it before the Queen. She looked around unseeingly, finally bent over it as Palmerston tapped it with his finger.

“The border between Canada and the United States is ill marked and runs through some very rugged country, or so I have been told. Apparently a party of American cavalry had crossed the border here and was apprehended by our patrol. Surprised in their trespass they opened fire in a most cowardly fashion, completely without warning. The militia, although only Colonials, fought back bravely and succeeded in repelling the invasion – though not without losses. A brave soldier wounded by gunfire is now at death’s door.”

“This is shocking, shocking.”

Queen Victoria was terribly upset, fanning her bright red face with her kerchief. She signaled to a lady-in-waiting and spoke to her. Lady Kathleen Shiel hurried away and returned with a glass of beer from which the Queen drank deep. This was some mark of her distress at the news, since she loved beer but rarely drank it with others present. Somewhat restored she sipped again from the glass and felt the anger rise within her.

“Are you informing me that my province has been invaded, one of our subjects killed by the Americans?” She shouted out the words.

“Indeed invaded. Certainly shot but…”

“I will not have this!” She was almost screaming now, infused by an intense rage. “There must be an answer to this crime. Something must be done. You say you discussed this all day. Too much talk. There must be some action.”

“There will be, ma’am.”

“What will it be? What has my cabinet decided?”

“With your permission, ma’am, we wish to send the Americans an ultimatum…”

“We have had enough of these ultimatums. We write and we write and they do exactly what they please.”

“Not this time. They will have seven days to respond. Their response must be the immediate release of the two Confederate commissioners and their aides. We also demand that we receive a letter of apology for this incursion into Your Majesty’s sovereign territory, as well as the attempted murder of one of Your Majesty’s subjects. Lord Lyons will personally carry this communication to Washington City and remain there for a week and no longer. We are firm in this intention. At the end of this period he will leave, with the response or without it, and return on the same steam packet that will convey him there. When he arrives in Southampton the response will be cabled to Whitehall.”

These firm words had calmed the Queen somewhat. Her mouth worked as she spoke wordlessly to herself. Finally she nodded in agreement and patted her damp face with her black kerchief.

“It is too fair – more than fair considering what has been done. They deserve worse. And what if the response is in the negative? If they refuse a reply and do not release the prisoners? What will my bold ministers do then?”

Lord Palmerston tried to ignore her agitated state. His voice was grave, yet very firm, when he responded.

“If the Americans do not accede to these reasonable demands all responsibility will lie with them. A state of war will then be deemed to exist between the United States of America and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.”

The silence that fell upon the room was more revealing of the feelings of those gathered there than any cry or spoken word might have been. All present had heard, all present understood the somber and momentous decision that must be made. All waited in deep silence for Queen Victoria to respond.

She sat stiffly in her chair, her hands lying on the black silk of her gown. Lady Shiel rustled forward and took the glass from her when she held it out. With a great effort the Queen drew herself together, forced herself to concentrate upon the matters to hand. She rested her hands on the arms of the chair, sat up straighten And spoke.

“Lord Palmerston, this is a grave responsibility and decision that my ministers have placed before me. But we cannot shrink from the truth, nor can we shy away from the conclusions that must then be reached.” She paused abstractedly before she spoke again.

“We are not pleased by what the Americans have done to our honor and our person. They will be punished.

“Send the ultimatum.”

THE ROAD TO WAR

The governor of the state of Louisiana, Thomas O. Moore, was a very worried man. He did not have to be reminded of this by higher authorities. He had sent for General Mansfield Lovell as soon as he had received the letter – and he waved it at him when the general entered the room.

“Lovell, we have Jefferson Davis himself worrying over our plight. He expresses great concern over the city of New Orleans and the threat against this city from two directions. Listen to this – ‘The wooden vessels are below, the iron boats are above; the forts should destroy the former if they attempt to ascend. The Louisiana may be indispensable to check the descent of the iron boats. The purpose is to defend the city and valley; the only question is as to the best mode of effecting the object.’ ”

“Does the President offer any suggestions as to what this best mode might be?” The general had a deep voice and a rich Louisiana drawl, sounding very much like the distant steam whistle of a riverboat.

“No he does not! Nor does he send any aid, troops, weapons or military supplies all of which we are in short supply. How goes the work on the Louisiana?”

“Slow, sir, mighty slow. It is the severe shortage of iron plate that is holding her back. But when she is done she will knock the living hell out of those bitty Yankee ironclads.”

“If she is ever completed.” Moore opened the jar on his desk and took out a cigar, sniffed it then bit off the end. Almost as an afterthought he passed one over to Lovell. “And if the bluebellies don’t attack first. I’m strongly minded of old General Winfield Scott’s anaconda speech. The Union will encircle the South like a great anaconda snake, encircle, squeeze and crush it. Well, I’ll tell you, Thomas, I’m feeling a tad crushed right about now. With those gunboats upriver just waiting for the chance to swoop down on us. The Feds have built up their forces on Ship Island at the mouth of the river, they’re in the passes and the river below Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip. A whole fleet of Yankee warships is out there downstream from New Orleans, along with a goodly number of transports filled with troops.”

“They won’t get past the forts, Governor.”

“Well they are trying hard enough. How many days now? Five at least that they been dropping mortar shells into those forts.”

“Hasn’t done the job yet, might never. And then there is the barrier.”

“A passel of old boats and a lot of chain across the river. Not much to put your faith in. Yankees upriver, Yankees downriver – and old Jeff Davis telling us to stand to our defenses, but without any help from him. I guess that I’ve seen blacker days, though I don’t rightly remember when.”

They puffed on their cigars until a cloud of blue smoke drifted across the desk. In silence, for there was little else that could be said.

Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut did not put much faith in the barrier either. But he didn’t like it there blocking his fleet from ascending the Mississippi. Porter’s mortar ships had been assailing the forts for five days now with no visible success. Farragut, never a patient man at the best of times, felt that his patience was now at an end. He had promised Porter six days to subdue the forts and the time was almost up. And the forts were still there. As was the barrier.

But at least he was doing something about that. It was now after midnight; he should try to get some sleep but knew that he could not. Brave men were out there in the night risking their lives. He paced the length of the USS Hartford’s deck towards the stern. Wheeled about to face the bow – just as the sky upriver lit up with a sudden burst of light. Seconds later the sound of the explosion reached their ears.

“By God they’ve done it!” He banged his fist on the rail.

They were the volunteers from Itasca and Pinola who had slipped upriver with explosives – but without weapons to defend themselves. They had counted upon darkness – and silence – to protect them. They had rowed away with muffled oars, their target the barrier in the river. If all went well they intended to plant their charges on the hulks there – hopefully without alerting the guards on the banks – set the fuses and get out. The fuses had obviously worked – pray the boats were out of reach before the powder had exploded. Farragut had a sudden vision of those brave young men, all dead. Volunteers, yes, and happy to go. But the plan had been his and he felt the weight of a terrible responsibility.

A long time passed, far too long Farragut thought, before they heard the creaking of oars in oarlocks and the dark form of a ship’s boat emerged out of the darkness. The boat from the Pinola drew up at the gangway and an officer hurried on deck.

“A success, sir. The charges were planted without the men being apprehended. The fuses were lit and all the boats were well clear before the explosions.”

“Any casualties?”

“None. A perfect operation.”

“A good night’s work indeed. My congratulations to them all.”

Unhappily, when the sun rose, the barrier was still there.

“But definitely weakened, sir. At dawn one of our boats got close enough to see that there are big chunks blown out of it. Hit it hard enough and it will give way.”

“I only hope that you are right, Lieutenant.”

Farragut went down to the wardroom where Porter and Butler were waiting.

“This is the sixth day, Porter, and your mortars appear not to have done the job. The forts are still there, their guns still covering the approach to New Orleans by river.”

“Just a little more time, sir – ”

“There is no more time. I said that you could have six days and you have had them. We must reach the city by other means. General Butler, you have had your scouts out there on both sides of the river. What do they report?”

General Benjamin F. Butler did not easily admit defeat. He scowled and bit down on an already well-chewed cigar. Then shook his head in a lugubrious no.

“There is just no way through. Water on all sides, all of the land low-lying and swampy. Then, just when you think you’re getting somewhere, you’ll come onto a waterway you can’t cross. Critters and bugs, snakes, gators, you name it. They thrive out there – but my soldiers don’t. Sorry.”

“Not your fault, nothing to be sorry for. You too, Porter. Your big mortars just aren’t big enough. Do either of you gentlemen see a way out of this impasse?”

“We could continue with the mortar attack on the forts…”

“That has proven not to be the answer. General Butler?”

“I would like to have some scouts take a closer look at those forts. They are the key to this entire engagement. If we could assess their strengths – and weaknesses – there might just be a less defended aspect. Using small boats we could land my troops at night, surprise and take the forts.”

Farragut shook his head in a slow no. “I think General, with no disrespect, that you have had little experience in landing troops. If you had you would recognize the folly of an undertaking like this. Landing soldiers from small craft, even on an undefended shore in daylight, is time-consuming and fraught with difficulties. I dare not consider the consequences of nighttime landings against defended positions. Are there any other suggestions? In that case we will just have to get to New Orleans in the only way that remains. Tonight we run the flotilla by the forts.”

“Wooden ships against iron guns!” Porter gasped.

“We will get by.”

“But the barricade across the river.” Butler shook his head.

“We will break it. We sail at two in the morning. We will move in two divisions. I will take the Hartford through last in the second division. The signal to begin will be two red lanterns on my mizzen peak. Here are the ship assignments to each of the divisions.”

The officers present looked at each other but did not speak. Duty called. It would be a brave attempt, some might even say foolhardy, but Farragut was in command and he would be obeyed.

Every ship had a full head of steam by two in the morning, ready to move when the signal was given. Telescopes were trained on the Hartford and the instant the two red lights appeared the attack began.

It was a dark night, with some low clouds, as the ships of the first division moved upriver. They revealed no lights and, at low speed, their engines were as silent as they could possibly be. The longer they proceeded without their presence being observed – the less time they would be under fire.

There was some trepidation as the barrier appeared ahead, pale against the dark river. The bow of the first gunboat sliced into it, carried it forward slowing the ship.

Then it broke and the joined, crushed hulks drifted away.

They were through the barrier, but the armed enemy was still waiting for them. Dimly seen against the night sky the dark masses of the two forts appeared ahead.

The quiet rush of water along the hull, the deep heartbeat of the engines was all that could be heard. One by one the ships of the first division slipped by the dark and silent forts and moved on towards New Orleans.

Without a shot being fired.

The second division was not as lucky. They had just reached the forts when the moon rose at three-forty. Unvigilant as the guards had been up until this moment, they could not miss seeing the ships in the bright moonlight. A shot was fired, then another and the alarm was raised.

“Full steam ahead,” Farragut ordered. “Signal all ships.” The sound of the engines would not matter now.

Both forts suddenly blossomed with fire and the cannonballs streaked across the river. There were some hits, but most of them skipped across the water in the darkness. The ships fired in return, flare of gunfire lighting up the night. Now the Union mortars added their thunderous roar and thick clouds of smoked drifted low across the river. It was a gauntlet of confusion and death, made even more menacing when Confederate fire rafts were launched against the Union’s wooden ships.

Yet in the end all of the ships made it past the forts into the silent waters beyond. There was some damage and three of the smaller vessels were badly disabled. Hartford was the last through. She had been hit but was still sound. Farragut watched with great satisfaction as the firing died away behind them. He had taken the risk – and he had won.

“Signal to all ships, well done. And I’ll want damage reports as soon as possible after we make anchor.”

Governor Moore did not sleep well that night. Worrying about the fate of the city had led him into drinking just a little bit more corn whiskey than he was used to. Then, when he had finally dropped off, thunder had awakened him. He had gone to the window to close it but there had been no sign of rain. The thunder was to the south; perhaps it was raining there. Could it have been gunfire? He tried not to consider this option.

He awoke at first light. There were carriages going by in the street outside and someone was shouting. A churchbell rang – yet this wasn’t Sunday. He went to the window and stared out at the ships tied up in the Mississippi River.

Looked past their masts and spars, looked in horror at the Union fleet in the river before him.

Then the ultimate shock, the ultimate despair. Not only was the Yankee fleet at their gates he realized, but the Louisiana, the ironclad that was being built to defeat these same Yankee ships, would never be launched to perform this vital task. She would be a great prize if she were taken by the Yankees. This had not been allowed to happen.

Instead of coming to the aid of New Orleans, she now floated, burning furiously, past the city and downriver towards the sea. The ironclad would never be launched, never fulfill her vital defending role he realized. All that effort, all that work, all for nothing.

She would soon sink, steaming and bubbling, to the bottom of the river that she was supposed to defend.

Scott’s anaconda, he realized, had tightened that little bit more.

“This is indeed wonderful news, Mr. President,” Hay said, smiling as he watched Lincoln read the telegram.

Lincoln smiled ever so slightly but did not speak. Since the death of little Willie something seemed to have gone out of him. A dreadful lassitude had overcome him and everything was a far greater effort than it had ever been before. He struggled against it, forced himself to read the telegram again and make some sense of it.

“I agree wholeheartedly, John. Wonderful news.” He spoke the words well enough, but there was no real sincerity in his voice. “Taking New Orleans is a stab right into the heartland of the Confederacy. From its sources to the sea the Mississippi River is now ours. I would almost tempt fate by saying that we are on the way to winning this war. I would be the happiest President in the White House if it weren’t for our British cousins and their stubbornness.”

Lincoln shook his head wearily and ran his fingers through his dark beard, the way he did when something was bothering him. Hay slipped out of the room. The President’s dead son was ever present in spirit.

The May evening was warm and comfortable, with only a slight suggestion of the damp, hot summer to come. The door to the balcony was open and Lincoln stepped through it and rested his hand on the railing, looking out at the city. He turned when he heard his wife call his name.

“Out here,” he said.

Mary Todd Lincoln joined him, clutched tightly to his arm when she saw the torchlit crowd in the street outside. She had kept very much to herself after little Willie’s death and rarely left her room. At times it appeared to be more than melancholia, when she talked to herself and pulled at her clothing. The doctors were very guarded in their appraisals of her condition and Lincoln had real fear for her sanity. He mentioned this to no one. Now he put his arm about her but said nothing. The pain of the child’s parting was still so great that they could not talk about it. There was a stirring in the mob as some people left, others joined, and the sound of raised voices and an occasional shout.

“Do you know what they are saying?” she asked.

“Probably the same thing they have been shouting for days now. No surrender. Remember the Revolution and 1812. If the British want war – they got it. Things like that.”

“Father… what’s going to happen?”

“We pray for peace. And prepare for war.”

“Is there no way of stopping this?”

“I don’t know, Mother. It’s like an avalanche just rushing downhill, faster and faster. Get in front of it and try to stop and you will just get crushed. If I ordered Mason and Slidell released now I would be impeached or just plain lynched. That’s the mood of the day. While the newspapers add fuel to the fire daily, and every congressman has a speech to make about international affairs. They say that the war against the South is good as won, that we can fight them and anyone else who comes around looking for trouble.”

“But the English, will they really do this terrible thing?”

“You read their ultimatum, the whole world did when the newspapers published it. Our hands are tied. I did send back proposals for peace with Lyons – but they were rejected out of hand. We had to agree to their terms, nothing else. With Congress and the people in a stew like this, if I had agreed to the British demands I might as well just have fitted a noose around my neck.

“And their newspapers are worse than ours. They threw our minister, Adams, right out of the country. Told him not to come back without accepting their terms. He brought with him a bundle of London newspapers. No doubts expressed whatsoever. The gamblers over there are putting bets on the day when war will start and how long it will take to whup us. I feel that their politicians are in the same fix I am. Riding the whirlwind.”

“And the South…?”

“Jubilant. They have an immense lust for this new war and see Mason and Slidell as holy martyrs. Britain has already recognized the Confederacy as a free and sovereign nation. There is already talk of military aid on both sides.”

There was a burst of noise from the crowd now, and more torches as well, that lit up the file of soldiers guarding the White House. The lanterns of guard ships were visible in the Potomac, lights of other ships and boats beyond them.

“I’m going inside,” Mary said. “It is foolish I know, the night is so warm, but I’m shivering.”

“Unhappily, there is much to shiver about. Let me take you inside.”

Secretary of the Navy Welles was waiting inside, straightening his wig in the mirror. Mary slipped by him without a word.

“I assume the navy is doing well – as always,” Lincoln said.

“As always, the blockade is in place and drawing ever tighter. I just heard the word that the ex-Secretary of War had boarded ship for the long voyage to Moscow.”

“I thought he would be a fine man to represent this government in the Russian court.”

Welles laughed aloud. “He will soon be selling watered stock to the Czar, if he runs true to form. I wonder what they will make of the crookedest politician in these United States.”

“I wouldn’t assign him that prize too readily. There are an awful lot of others vying for that title.”

John Nicolay looked in. “The Secretary of War is outside, sir. He wonders if he could see you for a few minutes?”

“Of course.” He turned to Mary who smiled as she pressed his hand, then left the room. War and talk of war were just too much for her tonight.

“No bad news for me Mr. Stanton?” Lincoln asked his new cabinet member. He and Stanton rarely saw eye-to-eye – but Edwin M. Stanton was a wonder of efficiency after his incompetent predecessor, Simon Cameron.

“Happily not. I’ve just left a meeting of my staff and thought you should know the results. Until we know more of the British plans there is little we can do. Being in a state of war already I imagine we are about as prepared as we could possibly be. However we are taking special precautions in the north. It is a long border and scarcely defended. The militia that is not already serving has been called out and put on the alert. Welles will know more about the situation at sea.”

“Like you we are already at full alert. The only fact in this black world that pleases me is that the British have allowed their navy to run down since the Crimean War.”

“Have you heard from General Halleck?” the President asked.

“We have indeed. He has telegraphed that he has now taken up his new post in command of the Department of the North in New York City. As agreed General Grant has taken over Halleck’s post in the Department of the Mississippi. Sherman is with him and together their armies form a substantial barrier against any Rebel incursions.”

“And now we wait.”

“We do indeed…”

Running footsteps sounded down the corridor outside and, without knocking, John Hay burst through the door.

“Mr. President, a communication from… from Plattsburgh, New York. It has been delayed, the telegraph wires south of that city have been cut.”

“What does it say?”

Hay read from the paper in his hand, choked at the words, finally got them out.

“I am… under attack by British troops. Colonel Yandell, Plattsburgh Militia Volunteers.”