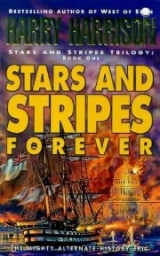

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes Forever"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Соавторы: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 11 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

The coastline was in sight now, flat and featureless and barely visible in the falling rain.

“It all looks the same,” the Duke of Cambridge said. “No obvious landmarks that I can make out.”

“It was a good landfall,” the admiral said. “After sailing by dead reckoning, for so long out of sight of land, I would say it was excellent navigation. The frigates are scouting both east and west and the island will soon be found.”

But it was noon before Clam came bustling back from her search. The fog had persisted and the drizzle still continued, which made her signals hard to read at a distance.

“Deer Island sighted. No ships at anchor,” the signal officer finally said.

“Capital,” the Duke of Cambridge said, feeling some of the tension drain away now that the final phase of the operation was about to begin. “Commander Tredegar, your marines will secure the landing beaches. As soon as you are ashore General Bullers will begin landing his men. Victory here, gentlemen, will be the first combined naval and army engagement that will lead inexorably to the final defeat of the enemy.”

As the ships approached the gray coastline the battlements of the shore defenses became more clearly seen. Admiral Milne had his telescope trained on them. The image was blurred by raindrops, so much so that he had to take it from his eye and wipe the object lens with his kerchief. When he looked again he laughed sharply.

“By George, there they are, sir. The Yankees, their flag.”

The Duke of Cambridge looked through his telescope at the stars and stripes above the ramparts. Red, white and blue.

“Send the order to begin firing as soon as the fortifications are within range. The boats will land under our covering fire.”

But it took time, too much time. No time was wasted by Tredegar’s experienced marines who were swiftly ashore and running up the beaches. But the soldiers of the regular army had no experience of beach landings and their attempts were glacial in the extreme. While the marines were attacking there was chaos among the army troops. The overloaded boats ran into each other, one capsized and the men had to be rescued and dragged from the sea. It was growing dark before the last of them were ashore and beaten into some kind of order by the sergeants. Major General Sir Robert Bullers used the flat of his sword against more than one of the dullards before he was satisfied enough to order his troops into the attack.

It proved to be desperately hard work. It was growing dark and the marines were still stalled before the earthen breastworks, the bodies of those who had fallen in the attack littering the sodden ground.

It was left to the 67th South Hampshire to do the job. They had been stationed on the island of Trinidad long enough for them to be able to work and fight in the clammy heat. Their sergeants had chivvied them into two lines now, muskets loaded, bayonets fixed.

“Hampshire Tigers – follow me!” General Bullers shouted and waved his sword as he started forward. With a roar of hoarse voices they charged past the colonel and into a hail of lead.

The standard bearer, just in front of the general, was thrown back as a minié bullet caught him in the stomach and doubled him over. Before his body fell the general had seized the regimental flag and saved it from falling into the bloody mud. He shouted encouragement, flag in one hand, sword in the other, until a corporal took the standard from him and charged on.

Although they were badly outnumbered the defenders still put up a stiff resistance. Two field guns had been landed and dragged into position. Under their merciless fire the ramparts were finally breached. But more good men fell in the attack that followed. It was a bloody business with hand-to-hand fighting at the very end.

Night had fallen before the rampart was finally taken – at a terrible price. The torn bodies of Bullers’s men and soldiers of the 56th West Essex mingled with the corpses of the defenders. A lamp was lit to look for survivors. There were very few. Blood and mud colored all of the uniforms, though it could be seen that the Americans were motley clad, not only in blue but with many other rags of uniform. Ill-uniformed or not – they could fight. And run – but not far. They must have formed a second line because gunfire crackled again and the air screamed with bullets. The lantern was quickly doused.

“They’ll rue this day’s work,” Bullers said through tight-clamped teeth, as his officers and noncoms ordered their lines. Some of the wounded were sitting up while others were lying in the mud with empty eyes; the walking wounded stumbled to the rear.

“Fire when you are sure of your target – then it is the bayonet. Forward!”

Men died in the night of fierce hand-to-hand combat. The Yankees would not retreat and every yard of advance had to be fought for. Men struggled in the mud and drowned in water-filled muddy ruts. In the end the relentless pressure of the British was too much for the outnumbered defenders and the survivors were forced to fall back. But it was not a rout. They kept firing as they retreated and held onto their guns.

The officers had put out pickets and, tired as he was, the general made the rounds with the sergeant major to be sure they were alert. The desperately tired soldiers drank from their water bottles and ate what bits of food they had in their packs. Fell asleep in the warm rain, clutching their muskets to their chests.

Just before dawn the cries of the pickets and a sudden crackle of gunfire heralded a counterattack. The weary soldiers rolled over and once again fought for their lives.

Surprisingly, the attack was quickly broken, a last weary attempt by the defenders. But the British soldiers after days at sea, a night of fighting and dying, little water and less sleep, would not be stopped now. Anger replaced fatigue and they pursued the running enemy in the gray dawn. Bayoneting them in the back as they fled. Chased them into the buildings beyond.

And found drink there. Large stone jugs of potent spirits that tore at their throats and burned in their guts. But there were barrels of beer as well to wash away the burn. And even better.

Women. Hiding, running, screaming. The trained British troops rarely broke down. But when they did so – as they did during the Indian Mutiny – the results were drastic and deadly. Now inflamed by drink and exhaustion, angry at the deaths of their comrades, the beast was released. The clothes were torn from the women’s bodies and they were pressed down into the mud and taken with fierce violence. And these soldiers, consumed by lust and drink, could not be easily stopped. One sergeant who attempted to intervene got a bayonet through his kidneys; the drunken men roared with laughter as he writhed in twisted death agony.

General Bullers did not really care. He ordered his officers not to intervene lest they risk their own destruction. The soldiers would fall down drunk soon, unconscious and stuporous. It had happened before; the British common soldier could not be trusted with drink. It had happened in India during the Mutiny – and even in Crimea. Now they would drink themselves stupid. In the morning the sergeants and the few teetotalers in the regiment would drag them under cover until they came around. To face whatever punishment he decreed. Lights appeared as bandsmen with lanterns came searching for survivors among the dead.

The general shook his head, realizing suddenly that he was close to exhaustion. A South Hampshire private stumbled out of a shed in front of him, stopped and drank from the crock of spirits that he had found. He dropped, stunned unconscious, when Bullers caught him a mighty blow on the neck with his fist. The general picked the jug out of the mud and drank deep and shuddered. Good whisky from the Scottish isles it was not. But it had an undeniable potency that was needed right now. Bullers swayed and sat down suddenly on the remains of a rampart, pushing aside a corpse to do so. The whiskey was tasting better with each swallow.

The dead soldier had been lying on a flag, clutching it in clawed fingers, perhaps trying to shield it from the carnage. General Bullers pulled it up and wiped some of the mud from it. Saw in the light of a passing lantern its colors. Red, white and blue. He grunted and dropped it back onto the corpse. Red, white and blue, the colors of the flag of the United States of America. Yes, but somehow different. What? He seized it up again and spread it on the rampart.

The correct colors all right. But differently shaped, arranged. This was not the stars and stripes he had seen flying from Yankee ships in Kingston harbor. This one had a few stars on a blue field, and only a few large horizontal stripes.

The flag moved in his hands and he started. Blinked and saw that the dead man’s eyes were open – mortally wounded perhaps, but not yet dead.

“This flag, what is it?” Bullers asked. The wounded man’s eyes misted so he shook him cruelly. “Speak up man, this flag, this is the stars and stripes?”

The dying soldier strained to speak, squeezing out the words and the colonel had to lean close to hear them.

“Not… damned Yankee flag. This… is the stars and bars… flag of the South.”

That was all he said as he died. General Bullers was stunned. For a single horrified moment he believed the man, believed that this was the flag of the Confederacy.

Had he attacked the wrong side? That could not be possible. He knew the flag of the Confederacy with its crossed blue bands with white stars on a red background. He had seen it on blockade runners tied up at the Pool in London. And this was certainly not the same.

And no country, even these miserable colonials, could possibly have two flags. Or could it? No! The man had lied, lied with his dying breath, may he burn in Hades for that. He held the flag in his hand and turned it about. Then hurled it into a mud-filled puddle and ground it under his heel.

What the hell difference did it really make, either way? North or South they were all filthy backwoodsmen. Sons and grandsons of the colonial revolutionaries who had had the temerity to fight and kill good Englishmen. Including his good father, Lieutenant General Bullers, who had fallen at the Battle of New Orleans.

He drank heavily from the stone crock and twisted his boot back and forth until the last scrap of flag had disappeared in the filthy mud.

Then sighed – and pulled it out again. Whatever flag it was, whatever had happened here, the Duke of Cambridge would have to know about it.

The duke had moved his headquarters to a stone blockhouse, close to the beach, that had been part of the defending gun battery. He was shuffling through a handful of half-burned reports when Bullers came in with the flag.

“Most strange,” the duke said. “These reports are all headed CSA – not USA. What the devil is going on here?”

Bullers held out the battered flag. “I think – Your Grace – I think that a terrible mistake has been made. There are no Yankees here. For some reason, I don’t know, we have been fighting and killing Southerners.”

“Good God!” The duke’s fingers opened and the papers fell to the floor. “Is that true? Are you sure of it?”

Bullers bent and picked up the papers, shuffled through them. “These are all addressed to the forces in Biloxi. A coastal city in Mississippi.”

“Damn and blast!” The duke’s amazement was replaced by a boiling rage. “The navy! The senior service with their much-vaunted skills of navigation. Couldn’t even find the right bloody place to attack. So where does that leave us, Bullers? With egg on our face. Their mistake – our blame.”

He began to pace the length of the room and back. “So what do we do? Retire and apologize? Not my way, General, not my way at all. Crawl away with tail between legs?”

“The alternative…”

“Is to carry on. We have the men and the determination. Instead of aiding this nauseous slaveocracy we shall defeat it. Strike north to Canada and destroy everything in our path. Defeat this divided and weak country, countries, now and bring them all back into the Empire where they belong.

“Strike and strike hard, Bullers. That is our only salvation.”

A MUTUAL ENEMY

After the first year of the Civil War both sides in the conflict had learned how important it was to dig in – and dig quickly. Standing up and firing shoulder-to-shoulder, Continental style, had proven to be only a recipe for suicide. If there were any possibility of an attack the defenders dug in. With shovels if they were available. With bayonets, mess kits, anything if they were not. They became very good at it. In no time at all trenches were dug and dirt ramparts thrown up that would stop bullets and send cannonballs bouncing to the rear.

With memories of the blood-drenched Battle of Shiloh still fresh in their minds, the survivors dug. The 53rd Ohio were now entrenched on top of the high bluff above Pittsburg Landing. Chunks of branches and trees, blasted during the fighting there, were embedded in the red dirt of the rampart.

Knowing how weak his manpower was, now that General Grant had taken the bulk of the army east to face the British invasion, General Sherman had done his best to reinforce the defenses. He had mounted all of his guns forward so they could spray any attack with canister shot, tin canisters of grapeshot that burst in the air over the enemy. This line would have to be held against the far superior force of the Confederates. He wondered how long it would take them to discover his diminished strength; not long, he was sure.

At least he could rely on the gunboats tied up at the landing. He and his signals officer had spent long hours with the captains of the vessels to ensure that covering fire would be fast and accurate. He felt that he had done all that he could do in the situation.

Now that the spring floods were over, the Tennessee River had fallen, exposing sandbanks and meadows beside the landing. Sherman had put up tents and made his headquarters there beside the river. The messenger found him in his tent.

“Colonel says to come and git you at once, General. Something’s happening out where the Rebs is camped.”

Sherman climbed the high bank and found Colonel Appier waiting there for him. “Some kind of parlay going on, General. Three Secesh on horses out there. One blowing a bugle and the other waving a white flag. Third one got plenty of gold chicken guts on his sleeve, ranking officer for sure.”

Sherman clambered up onto the parapet to see for himself. The three riders had stopped a hundred paces from the Union position; the bugle sounded again. The bugler and the sergeant with the flag were riding spindly nags. The officer was mounted on a fine bay.

“Let me have that telescope,” Sherman said, seized and held it to his eye. “By God – that is General P.G.T. Beauregard himself! He visited the college when I was there. I wonder what he is doing out there with a flag?”

“Wants to parlay, I guess,” Appier said. “Want me to mosey over and see what he has to say?”

“No. If one general can ride out there I guess two of them can. Get me a horse.”

Sherman dragged his skinny frame into the saddle, grabbed up the reins and kicked his mount forward. The horse picked its way carefully through the branches and litter of the battlefield. The bugler lowered his bugle when he saw Sherman approaching. Beauregard waved his men back and spurred forward toward the other rider. They came together and stopped. Beauregard saluted and began to speak.

“Thank you for agreeing to parlay. I am…”

“I certainly do know who you are, General Beauregard. You visited me when I was director of Louisiana State Military College.”

“General Sherman, of course, you must excuse me. Events have been – ” Beauregard slumped a bit in the saddle, then realized what he was doing and drew himself up sharply and spoke.

“I have just received telegraphed reports as well as certain orders. Before I respond I wished to consult with the commander of your forces here.”

“At present I am in command, General.” He did not go into detail why, since he did not want to discuss Grant’s departure and his weakened position. “You can address me.”

“It is about the British Army. It is my understanding that they have invaded the Federal states, that they are attacking south into New York State from Canada.”

“That is correct. I’m sure that it has been reported in the newspapers. Of course I cannot comment further on the military situation.”

Beauregard raised his gloved hand. “Excuse me, sir, it was not my intent to draw you out. I just wanted reassurance that you knew of that invasion, so you would understand better what I have to tell you. I wish to bring you intelligence of a second invasion.”

Sherman tried not to reveal his distress at this news. Another invasion would make the defense of the country just that more difficult. But he knew of no other invading forces and did not want to reveal his ignorance. “Please go on, General.”

Beauregard was no longer the calm and gently mannered Southern officer. His fists clenched and he had to squeeze the words out through hard-clamped teeth.

“Invasion and murder and worse, that is what has happened. And confusion. There were reports from Biloxi, Mississippi, that a Union fleet was bombarding the shore defenses there. Whatever troops that could be gathered were rushed there to stop the invasion. It was a night of rain and battle with neither side giving way. In the end we lost – and not to the North!”

Sherman shook his head, confused. “I am afraid that I do not understand.”

“It was them, the British. Yesterday they landed troops to attack the defenses of the port of Biloxi. They were not identified until morning, when their flags and uniforms were seen. By that time the battle was over. And they were not simply satisfied with destroying the military. They attacked the people in the town as well, reduced it, burnt half of it. What they did with the women… The latest reports tell me that they are now advancing inland from Biloxi.”

Sherman was shocked speechless, just managed to murmur under his breath. Beauregard was scarcely aware of his presence as he stared into the distance, seeing the destruction of the Southern city.

“They are not soldiers, but are murderers and rapists. They must be stopped, annihilated – and my troops are the only ones in a position to do that. I believe you to be a man of honor, General. So I can tell you that I have been ordered to place my soldiers between these invaders and the people of Mississippi. That is why I requested this meeting.”

“Just what is it that you want, General?”

Beauregard looked grimly at his fellow officer, whom he had so recently engaged in deadly conflict. He thought carefully before he spoke.

“General Sherman, I know that you are a man of his word. Before this war you founded and led one of our great Southern military institutions. You have spent much time in the South and you must have many friends here. You could not have done this if you had been one of those wild-eyed abolitionists. I mean no insult, sir, to what I know to be your sincere beliefs. What I mean is that I can speak to you frankly – and know that you will understand how serious matters are. You will also know that in no way will I be able to lie to you, nor will you take advantage of anything that I might say.”

Beauregard drew himself up and when he spoke there was a grim fury behind his drawling words.

“I am asking you simply – if you will consider arranging an armistice with me at this time. I wish only to defend the people of this state and do promise not to undertake any military incursions against the Federal Army. In turn I request that you not attack my weakened positions here. I ask this because I go to attack our mutual enemy. If you agree you can draw up whatever terms you wish and I will sign them. As a brother officer in arms I respectfully ask you for your aid.”

This meeting, the invading British, the request were so unusual that Sherman really was at a loss for words. But he felt a growing elation at the same time. The armistice would be easy enough to arrange, in fact he would take a great deal of pleasure in doing so. His mission was to hold the ground he now occupied. He would far rather do that by joining a ceasefire than by bloody battle.

But even more important than that was the phrase that General Beauregard had used.

Mutual enemy, that is what he had said – and he had meant it. The very glimmer of a completely preposterous idea nibbled at the edges of his thoughts as he spoke.

“I understand your feelings. I would do the very same thing were I in your shoes. But of course I cannot agree to this without consulting General Halleck, my commanding officer,” he finally said.

“Of course.”

“But having said that, let me add that I have only compassion and understanding of your position. Grant me one hour and I will meet you here again. I must first explain what has happened, and what you propose. I assure you that I will lend my weight to the strengths of your arguments.”

“Thank you, General Sherman,” Beauregard said with some warmth as he saluted.

Sherman returned the salute, wheeled his horse about and galloped away. Colonel Appier himself seized the horse’s reins when Sherman dismounted.

“General – what’s it all about? What’s happening?”

Sherman blinked at him, scarcely aware of his presence. “Yes, Appier. This is a matter of singularly great importance or the general would not have come forward as he has done. I must make a report. As soon as that is done I will speak with you and the other senior officers. Please ask them to join me in my tent in thirty minutes.”

He went back down the slope to the encampment. But, despite what he had said, he made no attempt to go to the telegraph tent. Instead he went directly to his own tent. He spoke to the sentry on guard there.

“I am not to be disturbed until my officers assemble here. Tell them that they must wait outside. No one to be admitted to see me. No one at all – do you understand?”

“Yes, sir.”

He dropped into his camp chair and stared unseeingly into the distance, his fingers combing distractedly through his thin beard. There was an opportunity here, one that must be seized and grasped tightly before it escaped. Despite what he had said he had no intention of contacting Halleck, not yet. He needed time to think this through without any distractions. The course of action that he was considering was too personal, too irrational for others to understand.

Of course it was obvious just what he should do. It was his military duty to telegraph at once, to explain what had happened in Biloxi and to ask for orders. Surely when the generals and the politicians understood what the British had done, why then they would certainly agree to the armistice. A common enemy. Better having the Southern army fighting the British rather than threatening attack on the North.

But how long would it take the politicians to make their minds up?

Too long, he knew that. No one would want to take responsibility for the drastic action that Beauregard was asking for. Commanders would dither, then pass the decision on up the line. Dispatches would be telegraphed until, probably, the whole thing would end up in Abe Lincoln’s lap.

And just how long would that take? Hours at least, probably longer. And the decision must be made now. Hard as it was he must take the responsibility himself. Even at the risk of losing his career, he must decide. If this opportunity were missed it would never occur again. He must decide for himself and act on that decision.

And he knew what that decision must be. He went over every possibility, and still returned to the single course of action.

When his officers had gathered he told them what he was going to do. He measured his words carefully.

“Gentlemen, like the North, the South has now been invaded by a British Army.” He paused until this fact had sunk in, then went on. “I have just talked with General Beauregard who asked for a cease-fire to permit him to take his troops south to do battle with the enemy. He called the invaders ‘our mutual enemy’ and that is true. A cease-fire would certainly be very much in order at this time. It is certainly to our benefit as well.”

He looked around at the officers who were nodding agreement. But would they agree with him if he went further?

“I want to grant this cease-fire. What would you say to that?”

“Do it, General – by all means!”

“You must, there is no choice.”

“Every redcoat they whup is one that we won’t have to worry about.”

Their enthusiasm came naturally, was not contrived or exaggerated. But how far could he go?

“I am glad that we are in agreement on that.” Sherman looked around at his excited officers. Chose his words with great care. “I propose to render even greater aid to our common cause.

“If you agree with me, I am going to take a regiment of infantry and join General Beauregard in his attack on the British.”

The silence lengthened as they considered the impact of what Sherman was proposing. This went far beyond a single battle, a single joined conflict. There was the possibility of course that nothing would come of this decision other than a single battle – or it could lead to even more momentous events almost impossible to consider. It was Colonel Appier who spoke first.

“General, you are a brave man to suggest this without working up through the chain of command. I am sure that you have considered that and considered all of the possibilities of your actions. Well I have as well. I would like you to take the 53rd Ohio with you. The President has always looked for any means to shorten this war, to make peace with the Confederacy. I am in complete agreement with that. Let us aid in stopping this adventure, this invasion of our nation’s shores. Take us with you.”

A spark had been lit that burned all of them with enthusiasm. Captain Munch shouted agreement.

“Guns, you’ll need guns. My 1st Minnesota battery will go with you as well.”

“Will the men go along with this decision?” Sherman asked.

“I am sure that they will, General. They will feel just as we do – drive out the invaders of our country!”

While the orders were being issued Sherman went into his tent and wrote a report describing the actions he was taking, and why it was being done. He folded and sealed it and sent for General Lew Wallace in command of the 23rd Indiana.

“You agree with what is being done, Lew?” he asked.

“Couldn’t agree more, Cump. There is a chance here to do something about this war – although I am not clear just what will come out of it. After Shiloh and all those deaths I think I began to look at this war in a very different way. I do feel that what you propose to do is something that is well worth doing. Americans fighting Americans was never a good thing, even though it was forced upon us. Now we have a chance to do something bold – together.”

“Good. Then you will take command here until I return. And take this. It is a complete report of everything that has happened here today. After we have gone I want you to telegraph it through to General Halleck.”

Wallace took the folded paper and smiled. “Going to be busy around here for a bit. There are going to be some really great fireworks when this news arrives. I think it might be an hour or so before I’ll be able to get this out.”

“You are a sensible officer, Wallace. I will leave this matter to your discretion.”

The guns were limbered up, the horses fastened in their traces. An opening was torn in the defense line so that they could ride through. The men of the 53rd Ohio had been informed of what he planned to do and their reaction was important. They stood at attention as he rode up – then burst into wild shouting. Cheered him when he rode slowly by, waving their caps in the air on the points of their bayonets. Morale was high and no one seemed to doubt the grave importance or the correctness of his decision. Would the Confederates see it the same way? He looked at his watch: the hour was up.

He and Colonel Appier rode out to meet the waiting General Beauregard with the eyes of the army upon them.

Sherman chose his words carefully, fearful of any misunderstanding. “This has been a difficult and most important decision, General Beauregard, and I want to assure you that it is a universal one. I have told my officers about the British attack and we are of one mind. I have even spoken to the troops about what I plan to do and I assure you every man in my regiments is in agreement. The North and the South do indeed now have a common enemy.”

Beauregard nodded grimly. “I appreciate the decision. Then you do agree to a cease-fire?”

“Even more than that. This is Colonel Appier, the commanding officer of the 53rd Ohio. He, and every man in his regiment, agree with my decision as to what must be done.”

“I thank you, Colonel.”

Sherman hesitated. Was this the right thing to do – and how would Beauregard react? But there was no turning back now.

“There is more to this than just a cease-fire. We are riding with you, General. This regiment will aid you in your attack on the invading British.”

The General left him in no doubt about his reaction to Sherman’s decision. After one stunned moment of hesitation he shouted aloud and leaned over and grasped Sherman by the hand, pumped his arm furiously, turned and did the same with Colonel Appier.

“General Sherman you not only have the courage and courtesy of a Southern gentleman. But I swear by God on high that you are a Southern gentleman! Your years in Louisiana were not wasted ones. My call for aid has been exceeded in a manner I never thought possible. Bring your men. Bring your men! We march in common cause.”

General Beauregard galloped off to ready his troops. He never had a moment’s doubt about how they would react – and he was right. They cheered when he told them about Sherman’s decision, cheered louder and louder and threw their hats into the air.

They were ordered into ranks and stood at attention as the blue column of Yankee troops, Sherman leading the way, marched toward them, out from the defensive positions. A drummer to the fore beat the step while the fifes played a sprightly tune.