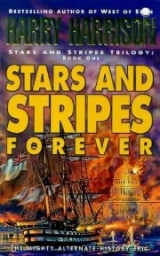

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes Forever"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Соавторы: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 21 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

When the last gun was silenced the wooden-hulled Roanoke had led the troop transports into the harbor. Resistance was slight – as expected. Spies had revealed that the garrison in Newcastle consisted of only four companies of the West India Regiment. The other regiments, infantry, Royal Engineers and Royal Artillery had been sent to the American campaign. The remaining regiment had been dispersed about the island and could not be assembled in time to prevent the Americans from landing. When the port had been taken and Government House seized, Grant had finished his report on the operation and taken it personally to Commodore Goldsborough on Avenger.

“Well done Commodore, well done.”

“Thank you General. I know that you have experience of combined army and navy operations, but this was an education to me. Is that the report for the President?”

“It is.”

“Excellent. I shall have it telegraphed to him as soon as I reach Florida to take on coal. I will get my ammunition and powder that I need in Baltimore, then continue north. At full speed. It is hard to realize in these salubrious islands that winter has arrived.”

“There is much to be done before the snow comes and the lakes and rivers freeze. General Sherman has his troops in position by now and is just awaiting word that you are on your way.”

“I am, sir, I am – with victory in my sights!”

THE BATTLE OF QUEBEC

The air was filled with the clatter of the telegraphs, the scratch of the operators’ pens as they transcribed the mysterious, but to them knowledgeable, clickings. Nicolay seized up one more sheet of paper and hurried to the President’s side.

“Montreal has been seized with unexpected ease. The ironclads bombarded the Royal Battery below the city, and the Citadelle above. The battery was destroyed and the Citadelle so knocked about that Papineau’s men took it on the first attack.”

“What about those Martello towers that General Johnston was so concerned about?”

“Papineau’s agents took care of that. The towers were manned by the local volunteer regiment of gunners – all French Canadian except for their officers. When the battle began they threw their officers out of the gun ports and turned their guns on the British. Within an hour of the first shot the defenders had either surrendered or ran. The Canadians are now in command.”

“Wonderful – wonderful! The doorway to Canada opened up – while Grant and Goldsborough have cleansed the West Indies of the enemy presence. I hope that I am not tempting fate when I say that the end may be in sight. Perhaps with a few more military disasters the British will reconsider their delaying tactics in Berlin. They must surely begin to realize that their disastrous adventure here must eventually end.”

“There is certainly no sign of it in their newspapers. You have seen the ones the French ship landed yesterday?”

“I have indeed. I was particularly enamored of that fine likeness of me with horns and pointed tail. My enemies in Congress will certainly have it mounted and framed.”

The President stood and walked to the window, to look out at the bleak winter day. But he did not see it, saw instead the bright islands in the Caribbean no longer British, no longer a base for raids on the American mainland. Now Montreal taken as well. Like iron jaws closing, the military might of a reunited United States was cleansing the continent of the invaders.

“It will be done,” the President said with grim determination. “General Sherman is in position?”

“He marched as soon as he received the word from General Grant that Jamaica had fallen and that Avenger was steaming north.”

“The die is cast, Nicolay, and the end is nigh as the preachers say. We offered peace and they refused it. So now we end the war on our terms.”

“Hopefully…”

“None of that. We have the right – and the might. Our future is in General Sherman’s most competent hands. Our joined armies are firm in their resolve to rid this country – if not this continent – of the British. I suppose, in a way, we should be grateful to them. If they had not attacked us we would still be at war with the Southern states. A war of terrible losses now thankfully over. Perhaps all hostilities will soon end and we can begin to think of a land at peace again.”

The kerosene light hung from the ridgepole of the tent, lighting up the maps between the two generals. Sherman leaned back and shook his head.

“General Lee – you should have my job, and not the other way around. Your plan is devastating in its simplicity, will be deadly and decisive when we strike the enemy.”

“We worked this out together you will remember.”

“I have assembled the forces – but the battle tactics are yours.”

“Let us say I have had greater experience in the field – and almost all of the time defending against superior forces. A man grows wise under those circumstances. And you are also forgetting something, Cump. Neither I nor any other general could take your place in command of our joined forces. No other Union general could command Southern troops and Northern troops at the same time. What you did for us in Mississippi will never be forgotten.”

“I did what had to be done.”

“No other man did it,” Lee said firmly. “No other man could have done it. And now that war between the states is over and, with God’s aid, it will soon be nothing but a bitter memory.”

Sherman nodded agreement. “May you be speaking only the truth. But I know the South almost as well as you do. Will there not be bitterness over the act to free the Negroes?”

Lee looked grim as he sat back in his camp chair, rubbed his gray beard in thought. “It will not be easy,” he finally said. “It is easy enough for a soldier to do, to follow commands. So we have the military on the side of justice, on the enforcement of the new laws. And the money will help see that all of the changes go down easily since most of the planters have been bankrupted by the war. The money for their slaves will put them back on their feet.”

“And then what?” Sherman persisted. “Who will pick the cotton? Free men – or free slaves?”

“That is something we must ponder upon – certainly the newspapers write of nothing else. But it must be done. Or all the death and destruction will have been in vain.”

“It will be done,” Sherman said with great sincerity. “Look how our men have fought side by side. If men who had recently been trying to kill each other can now fight shoulder-to-shoulder – certainly men who did not see war can do the same.”

“Some did not feel that way when the Congress of the Confederacy met for the last time.”

“Hotheads – how I despise them. And poor Jefferson Davis. Still attended by the doctors, his wound not healing well.”

Lee sat quiet for long minutes, then shook his head. “All that we have talked about, I am sure that it will work out well. Money for the planters. Jobs for the returning soldiers as the South begins to industrialize. I think that all of these tangible things will work, that slavery will be ended once and forever in this country. It is the intangibles that worry me.”

“I don’t follow you.”

“I am talking about the assumed authority of the white race. No matter how poor they are, what kind of trash, the Southerner doesn’t think but knows that he is superior to the Negro just by the color of his skin. Once things have settled down and the men are home they are going to look at free blackmen walking the streets – and they will not like it. There will be trouble, certainly trouble.”

Sherman could think of nothing to say. He had lived in the South long enough to know that Lee was speaking only the truth. They sat in silence then, wrapped in their own thoughts. Lee took out his watch and snapped the lid open.

“It will be dawn soon, time for me to join my troops,” Lee said, climbing to his feet. Sherman stood as well – and impulsively put out his hand. Lee seized it and smiled in return.

“To victory in the morning,” he said. “Destruction to the enemy.”

After General Robert E. Lee left, General William Tecumseh Sherman looked once more at the maps, once more went over the details of the attack. His aide, Colonel Roberts, joined him.

From the south bank of the river the city of Quebec loomed up clearly in the light of dawn. Sherman lowered his telescope and looked again at the map.

“It is just a little over a hundred years since Wolfe took the city,” he said. “Appears that little has changed.”

“If anything the defenses are stronger,” Colonel Roberts said, pointing at the upper city on the headland of Cape Diamond. “The walls and gun batteries have been built up since then. I would say that they are impregnable to frontal attack.”

“A frontal attack was never considered.”

“I know – but there was ice on the river last night.”

“Just a thin film. The St. Lawrence rarely freezes before the middle of December, almost two weeks from now. What we must do will be done today.”

“At least we don’t have to land men at Wolfe’s Cove and have them climb the path to the Plains of Abraham – as Wolfe did.”

Sherman did not smile; he found nothing humorous in war. “We shall not vary from our agreed plan of operation unless there is sufficient reason. Are the ironclads in position?”

“They went by during the night. Shore observers report that they are anchored at the assigned sites.”

“General Lee’s divisions?”

“Cleared out some British positions on the Isle of Orleans above the city. His troops are now in position there and on the St. Charles side of the city.”

“Good. There is enough light now. Start the attack on the gun positions at Point Lévis. Report to me when they are taken and our guns are in position.”

Sherman raised his telescope again as the telegraph rattled the command. An instant later the deep boom of cannon could be heard to the south, mixed with the crackle of small arms fire.

The British would be expecting an attack from the north, across the Plains of Abraham, the flattest and easiest approach to Quebec. Their scouts would have reported the advance of General Wallace’s divisions from that direction. So far, everything was going as planned. The armies north and south of the city, the ironclads in the river, the guns all in position.

There were shouts from the field behind the telegraph tent, a rattling and clatter as the wagons swung off the road. Almost before they had stopped the trained team of soldiers had started to pull out the crumpled yellow form and stretch it along the ground. Soon the sharp stench of sulfuric acid cut through the air as it was poured into the containers of iron filings. The lids slammed down and within minutes the hydrogen gas generated by the chemical reaction was being pumped through the rubberized canvas hose. As the balloon inflated more and more men grabbed onto the lines: it took thirty of them to keep it from breaking free. When the line was attached to the cage the observer and the telegraph operator climbed in. As the observation balloon rose the telegraph wire dangled down to the ground, all eight hundred feet of it.

General Sherman nodded approval. Now he had the eyes of a bird, something generals had been praying for for centuries. The iron frame of the telegraph in the wagon tapped out the first reports from the operator above.

It appeared that everything was going smoothly and to plan.

Within an hour the American cannon, and the captured British cannon, were firing their first shells into the besieged city.

“Can’t anything be done about that bloody contraption?” General Harcourt said, then stepped back as a shell struck the parapet nearby sending stone fragments in all directions. The yellow observation balloon hung in the still air, looking down into the besieged city.

“Sorry sir,” his aide said. “Out of range of our rifles – and no way to hit it with a cannon.”

“But the blighter is looking right down into our positions. They can mark the fall of every shell…”

A messenger ran up, saluting as he came. “Captain Gratton, sir. Reports troops and guns from the north. A field battery already firing.”

“I knew it! Plains of Abraham. They can read history books as well. But I am no Montcalm. We’re not leaving our defensive positions to be shot down. Going to see for myself.” General Harcourt swung into his saddle and galloped off through the city streets, with his staff right behind him.

The city of Quebec was now surrounded by guns. Those parts of it that could not be reached by gunfire from the opposite banks of the river were attacked by ironclads in the river. Some of these had mortars that lifted a 500-pound shell into a lazy arc up above the battlements, to drop down thunderously into the troops behind it. No part of the defenses was safe from the heavy bombardment of the big guns.

The ironclads were constantly on the move, seeking out new targets. Three of them, those most heavily armed, came together at exactly eleven o’clock, leaving the St. Lawrence and entering the St. Charles River that passed the eastern side of the city. At that same moment the yellow form of a second observation balloon rose from behind the protection of the trees and soared high into the air behind the warships.

The cannonade increased, explosive shells dropping with great accuracy on the defenses on this flank of the city. The telegraphed messages from the observation balloon were passed on to the gunships by semaphore.

When the bombardment was at its fiercest, the battlements blinded by the pall of smoke, General Robert E. Lee’s men attacked. They had landed on the city side of the river during the hours of darkness and had remained in concealment under the trees. The dawn bombardment had kept the British heads down so their presence had not been detected. The Southern force reached the crumbled defenses just as the British General Harcourt, on the far side of the city, was told of the new attack. Even before he could send reinforcements the attacking riflemen had gone to earth in the rubble and were firing, picking off any British soldier who stood in their way.

A second wave of gray-clad soldiers went through them, and still another. The rebel yell sounded from within the walls of Quebec; the breech had been made. More and more reinforcements poured in behind them, spreading out and firing as they attacked.

They could not be stopped. By the time General Sherman had boarded the ironclad to be ferried across the river there was no doubt of the outcome.

An entire division of Southern troops was now inside the city walls, spreading out and advancing. The defending general would have to take men from his western defenses. General Lew Wallace’s division had a company of engineers with them. Coal miners from Pennsylvania. Charges of black powder would bring down the gates there. Trapped between the pincers of the two armies and hopelessly outnumbered, the only recourse for the British was to surrender or die.

Within an hour the white flag had been raised.

Quebec had fallen. The last British bastion in Southern Canada was in American hands.

VICTORY SO SWEET

The cabinet meeting had been called for ten o’clock. It was well past that now and the President still had not arrived. He was scarcely missed as the excited men called out to each other, then turned their attention to Secretary of the Navy Welles when he came in, asking for the latest news from the fleet.

“Victory, just victory. The enemy subdued and overcome by force of arms, crushed and defeated. The islands of what were once called the British West Indies are now in our hands.”

“What shall we call them then?” Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War said. “The American East Indies?”

“Capital idea,” William Seward said. “As Secretary of State I so name them.”

There was a rumble of laughter. Even the stern Welles chanced a tiny smile as he ticked off points on his fingers.

“Firstly, the British are deprived of the only bases they have close to our shores. They have no port for their ships to be stationed in – whatever ships they have left – nor coal available for their ships’ boilers should they hazard more attacks from across the ocean. The murderous raids on our coastal cities must now cease.”

“But they can still raid from Canada.” Attorney General Bates was always one to find the worst in anything.

“If you substitute did for still you would be closer to the truth,” Edwin Stanton said. “The successful rebellion by the French nationalists has deprived them of their base in Montreal. The enemy flees before the advance of General Sherman’s victorious troops. Even as we speak he is drawing the noose around Quebec. When that noose snaps tight the British are doomed. Their troops will have to flee north and east to Nova Scotia where they hold their last naval base at Halifax…”

He broke off as the door to the Cabinet Room opened and President Lincoln entered. Just behind him was Judah P. Benjamin.

“Gentlemen,” Lincoln said, seating himself at the head of the table. “You all know Mr. Benjamin. Please welcome him now as our newest cabinet minister – the Secretary for the Southern States.”

Benjamin bowed his head slightly at the murmured greetings, shook the Secretary of State’s hand when Seward generously extended it, took his appointed seat.

“In previous meetings,” Lincoln said, “we have discussed the necessity of representation from the South. A few days ago Mr. Benjamin stepped down as appointed leader of the Confederacy when the last meeting of the Congress of the Confederacy was convened. He will tell you about that.”

There was a tense silence as Judah P. Benjamin spoke to them in his rich Louisiana drawl, a tone of unhappiness in his words.

“I will not lie to you and say that it was a pleasant time. The more level-headed gentlemen of the South were no longer present, some of them are already here in Washington and sitting in the House of Representatives. I will not go so far as to say that only the hotheads and the firm-minded were left, but there was indeed a good deal of acrimony. Some of them felt that the honor of the South had been betrayed. Motions were made and passions ran high. I am sorry to report that two more Congressmen were arrested when they threatened violence. In the end I had to bring in veteran troops who, having seen the bloody hell of war, would not let these men stand in the way of peace. Their commander was General Jackson who stood like a stone wall before the dissenters. Unmoved by pleas or curses, firm in his resolve, he saw to it that the last meeting of the Confederate Congress ended peacefully.”

He stopped for a moment seeing something they did not see. A country he had served, now vanished forever. He saw the South perhaps, soon to be changed beyond all recognition. He frowned and shook his head.

“Do not think that I weep for the fallen Confederacy. I do not weep, but can only hope, pray, that we can put the division of the states behind us. I ended the meeting, had those ejected who tried to remain, declared that the Confederate Congress had now ceased to exist. And then had the building sealed. I think I have done my part in the healing process. I now call upon you gentlemen, and the Congress of the United States to do yours. Keep the promises you have made. See that there will be an honest peace. If you do not do that – why then I have been part of the biggest betrayal in the history of mankind.”

“We will endeavor with all our will and strength to do just that,” the President said. “Now that the states of the South are sending representatives to Congress the wounds of our recent war must heal. But there will be problems in the process, none here would be so foolish as to deny that. During the past weeks I have worked closely with Judah P. Benjamin and have formed a bond. We are of like mind in many ways, and believe in the same future.

“To assure that future we must speak as one. This Cabinet must be firm in its resolve. Reuniting this country and binding up our wounds will not be easy. There are already reports of friction in the Southern states, about the purchase of slaves. We want to make sure that if and when problems arise they can be dealt with by Mr. Benjamin, who is not only knowledgeable in these matters, but is also respected and trusted in all parts of the former Confederacy.”

“There will always be hotheads and malcontents,” Benjamin said, “Particularly in the South where honor is held in great esteem and blood does run warm. The troubles that the President refers to are in Mississippi and I have already had correspondence about the matter. Simply put, it is the Reconstruction Act. While the details of purchase of slaves is spelled out, the prices to be paid are sufficiently vague to cause trouble. I intend to go to Mississippi at the soonest opportunity to thrash out details on the spot. We must make policy that is favorable and agreeable to all. If I can produce a workable agreement with the Mississippi planters I know that other plantation owners throughout the South will adhere to whatever rules we draw up.”

“Excellent,” Lincoln said. “This is the keystone of our agreement and it must work and work well.” He folded his hands before him in an unconscious attitude of prayer. “Our problems will multiply with time. In the past we have thought only of survival, of winning the war. With the armistice we ended one war to enable us to fight another. Here too we had but a single track to follow. We had to destroy our enemy and force him from our land. With the aid of our Creator we are doing that. But what of the future?”

He closed his eyes wearily, then snapped them open and sat erect. “We are no longer on a single track. Ahead of us are branch lines and switches that lead in many different ways. The mighty train of the Union must find its way through all hazards to a triumphant future.”

“And just exactly what will that be?” William Seward said. There would be a presidential election and his ambition for that office was well known.

“We don’t exactly know, Mr. Seward,” Lincoln said. “We must seek guidance in that matter. Not from the Lord this time, but from a man of great wisdom. He has shared this knowledge with Mr. Davis and myself, and recently with Mr. Benjamin, and was of great aid in preparing the Emancipation Bill. I have asked him here today to speak with you all, to answer grave questions like the last one. We will send for him now.” He nodded to his secretary who slipped out of the room.

“We have heard of your adviser. English is he not?” There was dark suspicion in the Attorney General’s voice.

“He is,” Lincoln said firmly. “As was this nation’s other great political adviser, Tom Paine. And, I believe, as were the founding fathers of the Republic. That is the ones who weren’t Scotch or Irish. Or Welsh.”

Bates scowled at the laughter that followed, but held his peace, unconvinced.

“Mr. John Stuart Mill, gentlemen,” Lincoln said as Hay showed him in.

“You can read the future?” the Attorney General asked. “You can predict what events will and will not happen?”

“Of course not, Mr. Bates. But I can point out pitfalls in your path to the future, and point out as well achievable goals.” He looked around calmly, very much in control of himself and of his words. “I wish to get to know you all much better. You gentlemen are the ones who will shape the future, for you and the President are the guiding stars of this country. So I will speak generally of these goals and what can realistically be obtained, and will then be happy to answer particular questions about your aspirations.

“I will speak to you of the importance of representative government, of the necessity of freedom of discussion. I am opposed to uneducated democracy, as I am sure you all are. These are abstractions that must never be forgotten, goals that must be achieved. But your first goal must be economic strength. You will win this military war. You will find it harder to win the peace, to win the economic war that must follow.”

Stanton’s brow was furrowed. “Do you speak in riddles?” he asked.

“Not at all. When you fought this war against the British you also fought a war against the British Empire. Have you ever looked at a map of this Empire, where the countries that sustain it are marked in pink? That map is pink, gentleman, and it is pink right around the world. There is a 25,000 mile circuit of the world where the British flag flies. The pink covers one-fifth of the Earth’s surface, and Queen Victoria rules one-quarter of the world’s population. The Empire is strong so you must be stronger. I know my countrymen and I know they will not suffer a defeat of the nature that you have forced upon them. I do not know what action they will take, but they will be back. So you must be prepared. The easy days in the South are at an end – although I realize that much of the way of the South is a myth and her people actually labor well and long. Your land is rich and your people, North and South, know the meaning of work. But the South must be just as industrialized as is the North. Subsistence farming does not make a country rich. The South must produce more than cotton to add to the national wealth. If you have the will you have the means. There is wealth in the soil, wealth to feed all of this country’s citizens. Wealth as well in iron, copper, gold.

“You must take this wealth and build a strong America. You can do this if you have the will. Seize the opportunity and lead the world by your example. The people of oppressed countries will see in you a glowing example of representative government. And, as my dear wife and daughter have pointed out to me, half of the citizens of the world are women. I owe much to them. Whoever, either now or hereafter, may think of me and the work I have done, must never forget that it is the product not of one intellect and conscience, but of three. Therefore you must one day consider the cause of universal franchisement.”

“Would you make that clearer?” Salmon Chase rumbled. “I do not understand your meaning.”

“Then I will elucidate. All here must surely believe in the bond that unites man and woman. Marriage is an institution that unites both sexes equally. For one cannot exist without the other. Women of intellect can match their male counterparts. They are equal before the law. They can own property. But in one thing they are unequal. They cannot vote.”

“Nor shall they ever!” Edward Bates called out.

“Why not, may I ask?” Mill said calmly.

“The reasons are well known. Their physical inferiority to men. Their nerves, their inconsistency.”

Mill would not be moved. “I feel that you belittle them, sir. But I do not wish argument now. I simply say that one day universal enfranchisement must be considered if this country is to be a true democracy representing all of its citizens. Not right now, but the issue cannot be avoided forever.”

“In the South we hold our women in great esteem,” Judah P. Benjamin said. “Though I hesitate to say that allowing them to vote would affect that esteem in a negative manner. And if one follows your logic to the very end – why you will next be thinking of allowing the Negro to vote?”

“Yes. In the long run the ideal universal suffrage must be taken under consideration as well. To be truly free a man must be sure that others are free. When others are chattels, either women or Negroes or any other group, then freedom is not complete. A true democracy extends freedom to all of its members.”

He paused for breath and touched his kerchief to his lips. Before he could continue there was a discreet knock at the door and secretary Hay entered.

“President Lincoln, members of the Cabinet, please forgive this interruption. But I know that you will want to hear the contents of this telegram.” He lifted it and read.

“Quebec is taken, the enemy is routed. Signed, General Sherman.”

In the silence that followed the President’s quiet words were clearly heard by all present.

“It is over then. The war is won.”