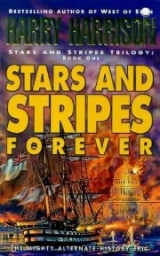

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes Forever"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Соавторы: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 10 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

INVASION!

The troops must have marched all night. Because there they were, trampling across the field of young wheat, just as the sun rose. A sentry called out for the colonel who appeared, sleepy-eyed and rubbing at his face.

“Redcoats!” The colonel snapped his mouth shut, realizing that he was goggling at them like a teenage girl. In double rank they marched slowly across the field toward the American defenses, then halted upon command. Their pickets were out ahead of the lines, shielding behind trees and dips in the ground. Groups of cavalry were stationed on either flank, while field guns were visible, coming up the road to their rear. Colonel Yandell snapped himself out of the paralysis and shouted.

“Sergeant – turn out the company! I want a message off to…”

“Can’t do it, sir,” the sergeant said grimly. “Tried to telegraph as soon as we saw them, but the wire must be down. Plenty of cavalry out there. Could easily have got around us in the night and cut the wire.”

“Something has to be done. Washington has got to know what is happening here. Get someone, get Anders, he knows the country around here. Use my horse, it’s the best we got.”

The colonel scrawled a quick note on his message pad, tore it off and passed it to the soldier.

“Get this to the railway station in Keeseville, to the telegraph there. Send it to Washington. Tell them to spread the word that we’re under attack.”

Colonel Yandell looked around grimly at his men. His volunteers were green and young and they were frightened. The mere sight of the army before them seemed to have stripped most of them of their senses. Some were starting to shuffle toward the rear; one private was loading his musket, although he already had loaded it with two charges. Colonel Yandell’s snapped commands had exacted numbed and reluctant obedience.

“Colonel, sir, peers like someone’s comin’ this way.”

Yandell looked through the nearest gun port and saw a mounted officer, resplendent in red uniform and gold braid, trotting toward the battlement. A sergeant walked beside him with his pike raised, a white flag tied on its end. Yandell climbed up to the top of the wall and watched their slow approach in silence.

“That’s far enough,” he called out when they had reached the bottom of the slope before him. “What do you want?”

“Are you the commanding officer here?”

“I am. Colonel Yandell.”

“Captain Cartledge, Seaforth Highlanders. I have a message from General Peter Champion, our commanding officer. He informs you that at midnight a declaration of war was issued by the British government. A state of war now exists between your country and mine. He orders you to surrender your weapons and guns. If you comply with his commands you have his word of honor that none of you will be harmed.”

The officer drawled out the words with bored arrogance, one hand on his hip the other resting on the hilt of his sword. His uniform was festooned in gold bullion; rows of shining buttons ran the length of his jacket. Yandell was suddenly aware of his own dusty blue coat, his homespun trousers with a great patch in the seat. His temper flared.

“Now you just tell your general that he can go plumb to hell. We’re Americans here and we don’t take orders from the likes of you. Git!”

He turned to the nearest militiaman, a beardless youth who clutched a musket that must have been older than he was.

“Silas – stop gaping and cock your gun. Put a shot over their heads. Don’t aim at them. I just want to see them skedaddle.”

The single shot cracked out and a small cloud of smoke drifted away in the morning air. The sergeant began to run and the officer pulled at his reins and spurred his horse back toward the British lines.

The first shot of the Battle of Plattsburgh had been fired.

A new war had begun.

The British did not waste any time. As soon as the officer had galloped back to the lines a bugle sounded, loud and clear. Its sound was instantly lost in the boom of the cannon that stood behind the troops, almost hub to hub.

The first shells exploded in the bank below the fortifications. Others, too high, screamed by overhead. The defenders clutched the ground as the gunners corrected their range and shells began to explode on the battlement.

When the firing suddenly stopped the day became so still that the men on the battlement could hear the shouted orders, the quick rattle of a drum. Then, with a single movement, in perfect unison, the two lines of soldiers started forward. Their muskets slanted across their chests, their feet slamming down to the beat of the drums. Suddenly there was a hideous squealing sound that pierced the air. These New York farmers had never heard its like before, had never heard the mad skirl of the bagpipes.

The attackers were halfway across the field before the stunned Americans realized it, struggled to their feet to man the crumbled defenses.

The first line was almost upon them. The Seaforth Highlanders. Big men from the glens, their kilts swirling about their legs as they marched. Closer and closer with the cold precision of a machine.

“Hold your fire until I give the order,” Colonel Yandell shouted as the frightened militiamen began to pop off shots at the attackers. “Wait until they’re closer. Don’t waste your ammunition. Load up.”

Closer, steadily closer the enemy came until the soldiers were almost at the foot of the grassy ramp that led up to battlements.

“Fire!”

It was a ragged volley, but a volley nevertheless. Many of the bullets were too high and whistled over the heads of the ranked soldiers. But these men, boys, were hunters and a rabbit or squirrel was sometimes the only meat they had. Lead bullets thudded home, and big men slumped forward into the grass leaving holes in the ranks.

The response to the American volley was devastating and fast. The front rank of soldiers kneeled as one, raised their guns as one – and fired.

The second rank fired an instant later and it was as though the angel of death had swept across the battlements. Men screamed and died, the survivors looked on, frozen, as the red-clad soldiers, with bayonets fixed, stormed forward. The second rank had reloaded and now fired at anyone who attempted to fire back.

Then their ranks parted and the scaling parties ran through them, slammed their long ladders against the crumbled defenses. With a roar the Highlanders attacked. Up and over and into the lines of the outnumbered defenders.

Colonel Yandell had just formed a second line to the rear, to guard the few guns mounted there. He could only look on in horror as his men were overrun and butchered.

“Hold your fire,” he ordered. “You’ll only kill our own boys. Wait until they form up for the attack. Then shoot and don’t miss. You, Caleb, run back and tell the guns to do the same thing. Hold their fire until they are sure of their targets.”

It was careful butchery, too terrible to watch. Very few Americans survived the attack to join the defenders in the second line.

Again the drums rolled and the big men in their strange uniforms lined up in perfect rows. And came forward. Their lines thinned as the Americans fired. Thinned but did not stop, formed up again as men moved into the gaps.

Colonel Yandell emptied his pistol at the attacking men, fumbled to reload it when he was addressed.

“Colonel Yandell. It is ungentlemanly to fire at an officer under a flag of truce.”

Yandell looked up to see Captain Cartledge standing before him. His uniform had been blackened by smoke, as had his face. He stepped forward and raised his long sword in mocking salute.

Colonel Yandell pointed the pistol and fired. Saw the bullet strike the other man’s arm. The English officer stumbled back under the impact, shifted the sword to his left hand and stepped forward.

Yandell clicked the trigger again and again – but he had only had time to load the one chamber.

The sword plunged into his chest and he fell.

One more dying American, one more victim of this new war.

The regimental carpenter had planed the plank smooth, then tacked on the sheet of white cartridge paper with a couple of nails. It made a rough but serviceable drawing board. A charcoal willow twig was a suitable drawing instrument. Sherman sat outside his tent concentrating on the drawing he was making of the landing and the steamboats behind. He turned when he heard the footsteps approach.

“Didn’t know that you could draw, Cump,” Grant said.

“It snuck up on me and I learned to like it. Did a lot of engineering drawings at the Point and just sort of fell into sketching. I find it relaxing.”

“I could use some of that myself,” Grant said, taking a camp chair from the tent and dropping into it. He pulled a long black cigar from his jacket pocket and lit it. “Never did like waiting. Johnny Reb is quiet – and the British! Why we just don’t know do we. I feel like latching onto a jug of corn likker…”

Sherman turned quickly from the drawing, his face suddenly drawn. Grant smiled.

“Not that I will, mind you,” he said. “That’s all behind me now that there is a war on. I don’t think either of us did well as we should when we were out of the army. But at least you were a bank president in California – while I was hauling timber with a team of mules and burying my face in the booze every night.”

“But the bank failed,” Sherman said grimly. “I lost everything, house, land, everything I had worked for all those years.” He hesitated and went on, his voice lowered. “Lost my sanity, felt that way at times.”

“But you came out of it, Cump – just the way I came out of the bottle. I guess war is our only trade.”

“And you are good at it, Ulysses. I meant it when I wrote that letter. I have faith in you. Command me in any way.”

Grant looked a little discomfited. “Not just me. Halleck said you should have the command under me. I was more than happy to oblige. You have good friends in this army, that’s what it comes down to.”

“General Grant, sir,” a voice called out and they turned to see the sergeant on the bank above. “Telegraph message coming through from the east. About the British the operator said.”

“This could be it,” Grant said, jumping to his feet.

“I’ll put this away. Be right with you.”

The military telegraph was still clicking out its message when General Grant came into the tent. He stood behind the operator, reading over his shoulder as he wrote. Seized up the paper when he was finished. He clamped down hard on his long cigar, then puffed a cloud of smoke over the operator’s head.

“Stuart,” he called out, and his aide hurried over. “Get my staff together. Meeting in my tent in half an hour. If they want to know what it is about, just tell them that we got a second war on our hands.”

“The British?”

“Damned right.”

Grant walked slowly back to his tent, chewing on his cigar and planning out just what he had to do. Sherman was already there, pacing back and forth. As Grant stamped into the tent he knew exactly what orders had to be issued, what actions taken.

Grant poured out a glass of whiskey from the stone crock and passed it over to Sherman. Looked at the jug and smiled grimly; then pushed the corn cob back into its neck.

“They’ve done it, Cump, actually gone and done it. We are at war again with the British. Without much reason this time. I don’t see how stopping one ship and taking some prisoners could lead to this.”

“I don’t think that there has ever been much reason for most wars. Since Victoria has been on the throne there has always been a war going on somewhere around the world for the British.”

“Little ones maybe, but this is sure going to be a big one.” Grant went over and tapped his index finger against the map that was spread across the sawhorse-supported table. “They invaded New York State right up here and attacked the fortifications at Plattsburgh.”

Sherman looked at the site of the attack, just south of Lake Champlain, and shook his head in disbelief, took a sip of his whiskey. “Who would have thunk it. The British always seem ready to fight the last war when the new one begins.”

“Or even the one before it. Stop me if I am wrong – but didn’t General Burgoyne come that way when he invaded the colonies in 1777?”

“He surely did. And that’s not all. Just to prove that the British never learn anything by experience, General Provost in 1814 did exactly the same thing and attacked in exactly the same way. Got whupped though and lost all of his supplies. Maybe that can happen again.”

Grant shook his head glumly. “Not this time, I’m afraid.” He sat back in his field chair and puffed on his cigar until the tip glowed red. He pointed the cigar at his fellow general and close friend.

“Won’t be as easy this time as it was before. All we got in front of them now is some militia with a couple of old cannon. The British field guns and their regulars will run right over those poor boys. The way I see it, it is not a matter of will they lose, but just how long they will be able to hold out.”

Sherman traced his finger down the map. “Once past Plattsburgh the invading army will have a clear track right down the Hudson Valley. If they’re not stopped they’ll go straight through Albany and West Point and the next thing you know they will be knocking on the door in New York City.”

Grant shook his head. “Except it is not going to be that easy. Halleck has already got his troops loaded onto the New York Central Railroad and is heading north even while we speak. As far as we can tell the enemy has not yet penetrated further south than Plattsburgh. A lot depends on how long the militia there can hold on. Halleck hopes to draw the line north of Albany. If he does I will join him there. He wants me to entrain with as many regiments as we can spare from here and come and support him.”

“How many are we taking?”

“No we, Cump. He is putting you in command when I am gone. How many troops will you need if Beauregard tries another attack at Pittsburg Landing?”

Sherman thought long and hard before he spoke. “For defense I’ll have the cannon on the gunboats that are still tied up on the riverbank. So I can fall back as far as the landing and make a stand there. If you can leave me four batteries and a minimum of two regiments I’ll say that we can hold the line. We can always cross back over the river if we have to. Beauregard won’t get through us. After Shiloh we’re not giving away an inch.”

“I think you had better have three regiments. The Rebs still have a sizable army out there.”

“That will do fine. Are hard times coming, Ulysses?”

Grant drew heavily on his cigar. “Can’t lie and say that things are going to be easy. Johnny Reb may be down but he is surely not out. And they’ll just love to see us being kicked up the behind by the lobsterbacks. But I don’t think that the Rebs will try anything for awhile. Why should they?”

Sherman nodded solemn agreement. “You’re absolutely right. They’ll let the British do their fighting for them. While their scouts watch our troop movements and keep track of us, they will have plenty of time to regroup. Then, when we’re tied up on the new fronts, why they can then just pick and choose exactly where they want to attack in force. I cannot lie. Far from being almost won, our war with the Secesh is about to begin to go very badly.”

“I’m afraid that you are right. They’ve got spies everywhere – just like us. They’ll know where we are weakening the line, and they will also know just what their friends the British are doing. Then, soon as they catch us looking away for a moment – bang – and the battle is on.”

Grant was silent for a moment, weighing their problems. “Cump, we have both had our problems in the past – in the army and out of it. Mostly out of it. I used whiskey to drown my problems, as you know.”

Sherman’s face was grim. “Like you, life has not been easy. All of the things I did when I left the army suddenly don’t seem that important. Before the battles started I was fearful and upset. Saw troubles where none existed. That’s all over. But funny enough, it is all a lot easier now. There seems to be clarity in war, a fulfillment in battle. I feel that I am in the right place at last.”

Grant stood and seized his friend’s hand, took him by the arm as well. “You speak the truth far better than you know. I have to tell you that. Some people’s facilities slow down and go numb when faced with battle. Others sharpen and quicken. You are one of those. They are rare. You held my right flank at Shiloh and you never wavered. Got a lot of good horseflesh shot out from under you too, but you never hesitated, not for one second. Now you have to do it again. Hold the line here, Cump, I know you can do it. Do it better than anyone else in this world.”

DEATH IN THE SOUTH

Alexander Milne, admiral of the British Navy, was a courageous and bold fighting man – when it was time to be courageous and bold. He had always been bold in battle, had been badly wounded in his country’s cause. When the Americans had seized a British ship and taken prisoners from it, he had gone at once to the Prime Minister and requested active service once again. This had been the right and bold thing to do.

He was also cautious when it was necessary to be cautious. Now he knew, as the squadron plowed ahead through the warm, star-filled night, that this was indeed a time for caution. They had been out of sight of land ever since his flotilla had sailed from the Bahamas at dusk two weeks ago, on a northerly course. The islands reeked with spies and his departure would surely be noted and transmitted to the Americans. Only when night had fallen and they were out of sight of land had the squadron turned south.

It had been dead reckoning ever since then, without a sight of land since Andros Island; a quick inspection at dusk of its prominent landmarks in order to check their position. It was good navigation training for the officers. They had sailed south almost to the Tropic of Cancer before they had altered course west through the Straits of Florida. They had held to this course since then, far out from the American coast and well clear of any coastal shipping. In all this sailing they had seen no other vessel, had assumed they had gone undetected as well.

It wasn’t until the noon sun observations agreed with the ship’s chronometer that they had indeed reached eighty-eight degrees west longitude that they had altered course for the last time. Sailed due north toward the Gulf Coast of the United States.

Admiral Milne flew his flag from the ironclad Warrior. He stood now on her bridge, besides Captain Roland who was her commander.

“How many knots, Captain?” he asked.

“Still six knots, sir.”

“Good. If the calculations are correct that should have us off the coast at dawn.”

Milne climbed up onto the after bridge and looked back at the ships keeping station astern. First were the two ships of the line, Caledonia and Royal Oak. Beyond them, just blurs in the darkness were the transports. Out of sight to their stern he knew were the other ships of the line, the frigates and corvettes. The largest British fleet that had been to sea since 1817.

But he was still not pleased. That a force this size had to circle out of sight of land – then slip in at night like a blockade runner – was a humiliating thing to have to do. Britain had ruled the waves for centuries and had won all of her wars that had been fought at sea. But the Americans had a large fleet guarding this coast and it must be avoided at all cost. Not because of fear of battle, but out of necessity of keeping their presence in these waters a secret.

Captain Nicholas Roland had joined him. “Clouding up ahead, sir,” he said. “Too late for the rainy season, but the weather can be foul along this coast at any time of the year.”

They stood in silence, each wrapped in his own thoughts, the only sound the metronome-like thud thud of the ship’s engines. Ahead of them the brilliant stars were vanishing behind the rising darkness of the approaching cloud. Out here, where the watch officer and the helmsman could not hear them, they could speak together as they could not in the crowded ship.

Roland was married to the admiral’s niece. Their homes in Saltash were quite close and he had seen a good deal of both of them when he had been recuperating from the wound that he had received in China, at the Battle of the Peio River. He and Roland had struck up an easy friendship despite their difference in years.

“I’m not sure, Nicholas, that I like the way warfare at sea is developing. We always seem to be a little bit late with engineering advances, too prone to let others lead the way.”

“I cannot believe that is true, sir. We are now standing on the bridge of the most advanced warship ever seen. Built of iron, steam-powered, with twenty-six 68-pounders, not to mention ten 100-pounders. A forty gun ship with guns of the largest caliber, unbeatable, unsinkable. We know that the senior service must be conservative, sir. But once we get our teeth into something we are a bulldog.”

“I agree. But far too often we tend to fight present wars with the skills of the past war. There is a weight of tradition and a tendency to suspect innovation that I feel will cost us dear.”

“That is possibly true, sir, but I am too far down the ladder to have an opinion. But surely you exaggerate. Just look at this ship. As soon as the navy discovered that the French were building La Gloire, an iron warship, there was the instant decision by the Secretary to the Admiralty to build an iron-belted frigate. Two of them in fact to go the French one better. Like our sister ship, Black Prince, we make the most of the modern science of the sea. We have sail as well as steam so we can stay at sea longer. I am most proud to command her.”

“You should be. But do you remember what I said when word reached us about the battle between Virginia and Monitor?”

“I can never forget it. We had just finished dining and you were passing the port. Robinson was deck officer and he came in holding the report, read it aloud to all of us. Some of the officers called it colonial tomfoolery but you would have none of that. You sobered them up quite quickly. ‘Gentlemen’, you said, ‘we have just entered a new age. This morning, when I awoke, the British navy had 142 warships. When I retire tonight we will have but two. Warrior and Black Prince.’ ”

“What I said then is still very true. Just as the steam engine put paid to the sailing ship, so shall the ironclad eliminate the wooden ship from the navies of the world. Which is why we are entering battle through the rear door, so to speak. The Yankee blockading fleet has effectively sealed off the southern coastline from any commerce by sea. Now I intend to break through that blockade and I have no intention of meeting any of the blockading fleet except under my terms. It is sheer bad luck that Black Prince is having her boilers repaired at this time. I would feel much better if she were at our side.”

Roland stamped his heel hard on the iron plating of the after bridge. “An iron ship that can carry the largest guns made. In her I dread naught.”

“I agree, a fine ship. But I wish her designers had not been so condescending to the Admiralty old guard. Sail or steam, I say. One or the other and not a mixture of the two. With masts and sail we must have an enormous crew to tend them. To raise sail by hand, to even raise the screw by hand – needs two hundred hands to do that job. Where one steam winch would have sufficed.”

Captain Roland coughed politely, then got up the nerve to ask the question that had been bothering him since he had first been appointed to command this ship.

“Sir, perhaps it is out of place, but I must admit that I have always been bothered by this. After all, the merchant ships use steam winches…” His words ran out as he blushed, unseen in the darkness, sure that he had spoken out of turn. The admiral was aware of this, but took pity.

“We have been friends, my boy, for some time. And I can well understand your worries about your charge. And I know that you have a sound enough head not to repeat anything that I tell you in confidence.”

“Indeed, sir! Of course.”

“I was part of the committee that approved Warrior and her sister ship. Although I protested I was overruled. I said that the navy would rather look backward than forge ahead. My suggestions were overruled. All of the others believed that the sailors would be spoiled and grow lazy if machines did their work for them. Besides, it was felt, the exercise would keep them healthy!”

Captain Roland could only gape. He was almost sorry that he had asked. The ship’s bell sounded the change of watch. He went down to the upper deck, to the rifle-proof conning tower.

On the deck below George William Frederick Charles, the Duke of Cambridge, stirred in his berth when he heard the bell, wide-awake and cursing it. When he closed his eyes instead of blissful darkness and the Lethe of sleep he saw divisions of soldiers, batteries of cannon, military stores, plans – all the paraphernalia of war that had occupied his mind for weeks – months now. The steel box of a cabin closed in on him. He did not consider for a moment the ship’s Master who had been moved out of this cabin, now sharing an even smaller cabin with the Commander – or the hundreds of ratings who swung their hammocks in the even darker, closer, noisome chambers belowdeck. Rank had its place – and his was at the very top. The Duke of Cambridge, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army, cousin to the Queen, was not used to physical discomfort, in the field or off it.

When he sat up his head struck the candle holder above the bed and he cursed it soundly. When he opened the cabin door enough light came in from the passageway for him to find his clothes. Pulling on jacket and trousers he went out of the cabin, turned right and went into the captain’s day room; a spacious area lit by a gimballed kerosene light and airy from the scuttle in the ceiling above. Still resting on the sideboard was the excellent brandy he had sampled after dinner: he poured himself a good measure. He had just dropped into the leather armchair when the door opened and Bullers looked in.

“I’m sorry, sir, didn’t mean to disturb you.”

He started to withdraw but the duke called after him. “Come in, Bullers, do come in – not able to sleep?”

“The truth indeed. Soldiers at sea are about as useful as teats on a boar.”

“Well said. Enter and address the brandy, there’s a good fellow.”

Major General Bullers was commander of the infantry, next in rank below the duke. Both were righting soldiers who had served in Ireland, then in the Crimea.

“Bloody hot,” Bullers said.

“Drink up and you won’t notice it.” He sipped from his glass. “Champion should be well on his way to New York City by now.”

“He should indeed. With his divisions and guns there is no force in the Americas that can stand in his way.”

“Let it be so. God knows we spent enough time in planning and outfitting the expedition.”

“You should have commanded it – to ensure success.”

“Nice of you to say so, Bullers – but General Champion is more than able to handle a straightforward attack like the one from Canada. This one is where certain other skills will be needed.”

As one their eyes turned to look at the maps strewn on the mahogany table. Although they had gone over the plans for the attack countless times before, the maps drew them back, like iron filings to a magnet. They stood, taking their drinks with them, and strode across the room.

“The Gulf Coast of America,” the Duke of Cambridge said. “Yankee naval bases here and here and here. A fleet at sea guarding every harbor and inlet. While here at Hampton Roads I am sure that the Monitor and her attendant ships of the line still guard the bolt hole where the Virginia must still lie at rest. Admiral Milne has insisted that we avoid that bit of coast like the plague – and I couldn’t agree more. That fleet is less than six hundred miles away and I want it to stay that way. Of course there is this small naval force blockading Mobile Bay not more than fifty miles away. But they are of no threat to our superior force.” He tapped the chart lightly.

“But here is the enemy’s Achilles heel. Deer Island off the coast of the state of Mississippi. Invaded and seized by the North and now a base for their blockading fleet. That is our destination. At dawn we shall attack and destroy them with a naval bombardment. Then your regiments, and the marines, will land and seize the fortifications. The blockade will be broken. The navy shall remain on station there, protected by the shore batteries, to make sure that the blockade in this area is not restored. As soon as our landings are successful I’ll take a troop of cavalry and contact the Confederates – and Jefferson Davis in Richmond. The Queen herself has messages for him and I am sure that our welcome will be of the warmest. After that our merchant fleet will get cotton here, bring in military supplies in return. The South will grow strong – and very soon will be victorious. Our armies still attack in the North so the Yankees must divide their strength if they attempt to pry us from this base. Divide and fall, defeated. They cannot long survive. Between our invading armies and a rejuvenated Southern army. Might will prevail.”

Bullers shared his enthusiasm. “It will be over by winter, God willing. The United States of America will cease to exist and the Confederate States of America will be the legitimate government.”

“A worthy aim and a happy conclusion,” the duke said. “I care little what the politicians do with the spoils. I just know that a victorious army will prove Britain’s might to the world. Then our navy will also be able to expand its ironclad fleet, until once again mastery of the world’s oceans shall be ours.”

At dawn, as planned, the commanders of the landing party were rowed to Warrior. Their boats appeared suddenly out of the sea mist and the officers climbed most carefully aboard, since every rope and piece of wood or decking was slick from the fog and gently falling rain.