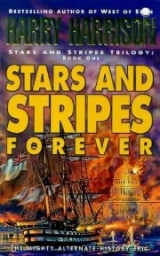

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes Forever"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Соавторы: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 8 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

SHILOH

Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston was of course a gentleman, as well as being a not unkind man. He wished for a moment that he was not a gentleman, so he would not have to see Matilda Mason. There was a war to be fought after all. No, that wouldn’t cut. All the orders had been issued, the troops deployed, so there was really nothing more for him to do until the attack began. She had been waiting to see him for two days now and he knew he could not put the meeting off any longer for he had run out of excuses. It was undeniable that she was indeed a close friend of his family so if word got back that he had refused to see her…

“Sergeant, show the lady in. Then bring a pot of coffee for some refreshment.”

The tent flap lifted and he climbed to his feet and took her hand. “It has surely been a long time, Matty.”

“A lot longer than it should have been, Sidney.” Still an impressive woman even though her hair was going gray. She sniffed, then crumpled into the canvas chair. “I am sorry, I should not speak like that. Lord knows you have the war to fight and more important things to do than see an old busybody.”

“That’s certainly not you!”

“Well indeed it is. You see, I am so worried about John, chained in that prison in the North, like some kind of trapped animal. We are so desperate. You know the right people, being a general now and all, so you can surely do something to help.”

Johnston did not say so – but he had very little sympathy for the imprisoned John Mason. He was reported to be living in some comfort, with all the best food – and he would surely never run out of cigars.

“I can do nothing until the politicians can come to some agreement. But look at it this way, Matty. There is a war on and we all must serve, one way or the other. Right now, in that Yankee prison, John and Slidell are worth a division or more to the Southern cause. The British are still fuming and fussing about the incident and making all sorts of warlike sounds. So you have to understand that anything that is bad for the North is good for us. The war is not going as well as we might like.”

“You will hear no complaints from me, or anyone else for that matter. You soldiers are fighting, doing the best you can, we know that. At home we all also do what we can to support the war. There is not an iron fence left in our town, all sent away to melt down for armor for the ironclads. If the vittles aren’t as good as we like that is no sacrifice in the light of what the boys in gray are doing. I’m not complaining for myself. I do believe that we are doing our part.”

“You don’t know how delighted I am to hear those words, Matty. I will tell you that it is no secret that the South is surrounded. What I want to do now is break through the Yankee armies that are choking us. I have had the army marching for days to face the enemy. And the attack begins tomorrow. Now that is a secret…”

“I’ll not tell!”

“I know that, or I wouldn’t be talking to you. I do this so that you will see that John, who is in reality quite comfortable where he is, is doing far more for the war where he is than he could in any other place. So please don’t trouble yourself…”

He looked up as his aide opened the tent flap and saluted. “Urgent dispatches, General.”

“Bring them in. You must excuse me, Matty.”

She left in silence, the lift of her chin revealing what she thought of this sudden interruption; planned no doubt. In truth it had not been, but Johnston was still grateful. He took a swig of the coffee and opened the leather case.

He, and every other general of the Confederacy, had been searching for a way to cut the noose that was strangling the South. They looked at the armies that encircled them and sought a way to break out. He had little admiration for Ulysses S. Grant, nevertheless he knew him to be an enemy of purpose and will. His victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson threatened continuing disaster. Now he was camped with a mighty army at Pittsburg Landing in Tennessee. Confederate intelligence had discovered that reinforcements were on the way to him. When they arrived Grant would certainly strike south into Mississippi in an effort to cut the South in two. He must be stopped before that happened. And Sidney Johnston was the man to do it.

His attack would be later than planned – but other than that it seemed to be going as well as could be expected. During the winter he had assembled an army even larger than Grant’s, which had been judged by the cavalry scouts to be over 35,000, and he meant to strike first, before Don Carlos Buell’s 30,000 men arrived to reinforce Grant. For three days now his raw recruits had been marching the muddy lanes and back roads of Mississippi, their weary columns converging on Pittsburg Landing. Now it was time for a final meeting with his officers.

They filed in one by one, drawing up chairs, pouring themselves coffee when he waved to the pot. He waited until they were all there before he spoke.

“There will be no more delays. We attack at daylight tomorrow, Sunday morning.”

His second-in-command, General P.G.T. Beauregard, was not quite so sure. “There is no longer the possibility of a surprise. They’ll be entrenched to the eyes. And our men, they’re just raw recruits and most of them had never heard a gun fired in anger.”

“We know that – but we also know that tired as they are from the march they are still filled with enthusiasm. I would fight the enemy even if they were a million. The attack goes on.”

“Do you have the time, Thomas? My watch has stopped,” General Sherman said. His orderly shook his head and smiled.

“Could never afford no watch, General,” Thomas D. Holliday said. “I’ll ask one of the officers.”

Brigadier General William T. Sherman and his staff were riding out in front of their camp, near Shiloh Church, on the banks of the Tennessee River. The morning mist had not lifted, so little could be seen under the trees and hedges. But the rain had stopped during the night and it promised to be a fine day. Sherman was worried, not happy at all with Grant’s decision not to have the troops dig in.

“Their morale is high, Cump,” Grant had said, “and I want it to stay that way. If they dig those holes and hide in them they are going to start worrying. We best let them be.”

Sherman still did not like it. There had been reports of movement on their front which had not disturbed Grant in the slightest. Nevertheless Sherman had led his staff out at dawn to see if there was any truth in the reports of the pickets that they had heard movement in the night.

Holliday turned his horse and trotted back to the general’s side.

“Just gone seven,” he said. And died.

The sudden volley of fire from the unseen Confederate pickets hit Holliday, blowing him off his horse and killing him instantly.

“Follow me!” Sherman shouted, turning and galloping toward their own lines. A Union picket burst out of the thicket ahead and called out.

“General – the Rebs is out there thicker than fleas on a hounddog’s back!”

It was true. They were three battle lines deep and were attacking all along the front. A victorious Rebel yell rose up as they crashed into the unprepared Northern positions, forced them back under a withering fire from their guns. Caught out by the surprise attack the soldiers wavered, favoring retreat to standing up to the hail of bullets.

Then, riding between the enemy and his own lines, General Sherman appeared. He seemed oblivious to the bullets now streaking past him as he stood in his stirrups and waved his sword.

“Soldiers – form a line, rally on me. Fire, load and fire. Stand firm. Load and fire!”

The General’s fervor could not be denied; his cries inspired the soldiers, who moments before had been about to run. They stayed at their positions, firing into the attacking troops. Load and fire, load and fire.

It was desperately hard and deadly work. This was the most exposed flank of the Union army and the heaviest attacks hit here. Sherman had eight thousand men to begin with – but their numbers withered steadily under the Confederate attack. Yet the Northern line still held. Sherman’s regiments took the brunt of the attack – but they did not retreat. And the general stayed in the midst of the battle, leading them from the front, seemingly oblivious to the storm of bullets about him.

When his horse was shot from under him he fought on foot until another mount was found and brought up.

Within minutes this horse was also killed while the general was leading a counterattack, and later on a third one that he was riding was shot dead as well.

It was a hot, hard, dirty and deadly engagement. The green Confederate troops, those who survived the bloody opening of battle, were learning to fight. Again and again they were rallied and sent forward to attack. The Union lines were driven back slowly, fighting every foot of the way, taking great losses – but still they held. And Sherman was always there, rallying the defenders from the fore. Men fell on all sides but still his troops held their positions.

Nor was he immune from injury; later in the day he was wounded himself, shot in the hand. He wrapped a handkerchief about the torn flesh and fought on.

A fragment of shell took off part of the brim of his hat. Despite this, despite the casualties, he stayed in command of his troops and managed to stabilize their positions. Three hours after the battle had begun Sherman had lost over half of his men. Four thousand dead. But the line held. Their powder and ball were so low that they had to plunder the supplies of the fallen. The wounded, who had not stumbled, or been carried, to the rear, loaded weapons for the men who fought on. Then, during a hiatus in the battle while the enemy regrouped, Sherman heard someone calling his name. The captain on the exhausted horse threw a rough salute.

“Orders from General Grant, sir. You are to fall back to the River Road.”

“I will not retreat.”

“This is not a retreat, sir. We have dug in on the River Road, positions that can be better defended.”

“I’ll leave skirmishers here. Keep them firing as long as they can. In the smoke they could slow the next attack some. Tell the general that I am falling back now.”

It was a fighting retreat. Disengaging from a determined enemy can be as difficult as holding them at bay. Men fell, but almost all of the survivors reached the River Road through the smoke and thunder of cannon.

“Them’s our guns, General,” one of the soldiers cried out.

“They are indeed,” Sherman said. “They are indeed.”

This was the first day of the Battle of Shiloh. The carnage was incredible. Despite their mounting losses the Confederate advance continued, slow and deadly. It wasn’t until five-thirty in the afternoon that the Union left was finally penetrated – but by then it was too late. General Grant had managed to establish a defensive line, studded with cannon, just before Pittsburg Landing. With the help of cannon fire from the gunboats tied up at the landing the last Confederate attack was thrown back. As this was happening Grant’s defenders were reinforced by the fresh troops of Don Carlos Buell who began to arrive on the other bank of the river.

The Confederate forces were bloodied and exhausted and no match for the strengthened Northern divisions.

The counterattack began the next day at dawn and by afternoon all of the lost ground had been recaptured.

If there was any victor in this carnage it had to be the North. They were now reinforced and back in their original defensive positions – but the cost had been terrible. There were 10,700 Confederate casualties, including their commander General Johnston, who had been shot and had bled to death because the doctor who might have saved him was treating the Union wounded. 13,000 Union troops were dead as well. Despite the courage, despite the sacrifices and the dead, the South had proved itself incapable of breaking out of the ring of steel that was closing around them.

Grant and Sherman were the heroes of the day. Sherman who had held the line despite his personal injuries and the terrible losses his troops had suffered.

“He must be rewarded for his bravery,” Lincoln said when he had read the final reports of the battle. “John, get a letter to the War Department and tell them that I strongly recommend that Sherman be promoted to major general, in acknowledgment of his bravery and strength of command. Talent like this should not go unacknowledged. And have the promotion dated back to April seventh, the day the battle was fought.”

“Yes, sir, I’ll do that at once. Will you be able to see Gustavus Fox now?”

“By all means. Show him in.”

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Gustavus Fox was a very talented man. He was familiar with the White House because Lincoln’s secretaries lived across the hall from the President’s office and he was a frequent visitor there. This apparent socializing provided an unquestioned cover for his visits. For Gustavus Fox had authority and commissions that only those in the highest echelon of government knew anything about.

“Good morning, Gus. Do you have any reports of interest to me?” the President asked.

“A good deal since last we met. My agents in Canada and the British West Indies have been quite diligent.”

“Is one of them Captain Schultz of the Russian Navy?”

Lincoln’s smile was mirrored on Fox’s face. “Not this time, Mr. President – he is busy elsewhere. But before I report on the British – I must tell you that my trip to Brooklyn was a great success. After the victory of the Monitor in Hampton Roads, and the navy’s agreement to put more money into iron warships, Mr. Ericsson was more than eager to proceed. Construction on the second Monitor-class ironclad is proceeding as planned. Very smoothly in fact since the ironworkers are now experienced with this particular kind of construction. Ericsson is now devoting his time to improving the design and construction of a larger iron ship with two turrets. Much more seaworthy and with greater range. The man is a demon for work – the keel was laid that very day for the USS Thor”

“I doubt that the navy will approve of a pagan deity in their fleet.”

“They didn’t. They withheld their first payment until Thor went back to Valhalla and Avenger emerged in his place.”

He took a sheet of paper from an inner pocket and unfolded it. His secret agents in the field had been busy indeed. Here were the names and strengths of the regiments of British troops newly arrived in Canada, as well as the number of guns unloaded on the docks of Montreal.

The President looked grim. “That sounds like a powerful lot of soldiers to be sending over here.”

“More than an army corps. And I have some reports that more are on the way, but I haven’t confirmed them yet. The British Navy has been busy too.”

He read from the list of navy warships based in the British West Indies, as well as giving an account of newly arrived reinforcements to the marines also based there. The President never asked who the men and women were who sent in these reports, while Fox never volunteered the information. If a report was doubtful, or possibly false, he would say so. The rest of the information had always proven to be correct.

“You are my eyes and ears,” Lincoln said. “I wish that you could find a way to convince Mr. Pinkerton that your reports are far more reliable than those furnished by his agents in the South.”

“I have tried many times, in roundabout ways, but he is a very stubborn man.”

“General McClellan believes in him.”

“General McClellan also believes in the inflated figures for Southern troops that Pinkerton comes up with. The real number is a third, at most a half of what he reports.”

“But McClellan remains sure that the numbers are correct and once more finds a reason to avoid action. But he is my responsibility and not yours. So, tell me – what conclusions do you draw from all these facts about the British that you have just presented?”

Fox thought carefully before he spoke, summoning up his conclusions. “The country is preparing for war in North America. They have the men, the weapons, the supplies and the ships to wage a major war on this continent. Most important of all is the fact that there are no voices of dissent. The newspapers call for war to teach us a lesson. Whigs and Tories unite in Parliament baying for blood. The Queen now believes it as a certainty that we killed Prince Albert.”

“Certainly that is absurd.”

“To us perhaps. But I am reliably informed that there is worry about her sanity, that she has sudden vicious obsessions that she cannot control.”

“Are there no sane voices to be heard?”

“It is imprudent to go against the public will. A certain baronet in the House of Lords was so unwise as to speak of a possible search for peace. He was not only shouted down but physically assaulted.”

“This is hard to believe, but I suppose I must. But will they do it? Take the final step?”

“You can answer that far better than I can, Mr. President. You are privy to the negotiations over their ultimatum, while I am not.”

“There is little I can tell you that you don’t already know. We want to talk, but I fear that they do not want to listen. And I am beginning to think that we have run out of options. Our newspapers and theirs are filled with fire and brimstone. Their ministers are just as ardent. Lord Lyons has given us his passports and vacated our shores. Our minister Charles Adams does his best to have London accept a rewording of their dispatch, but they agree to nothing. Now Lord Palmerston keeps him at bay and will not admit him to his house, although Adams has called repeatedly at that gentleman’s door. The lord pleads gout as the reason. I believe in the gout but not the excuse.”

Fox nodded agreement. “Meanwhile the cause of all this, Mason and Slidell, live a life of great luxury in their prison cells. Ordering the best food and wine from Boston and smoking their way through their bottomless supply of Havana cigars.”

“Luxury it may be – but they are still imprisoned. And as long as they are the Britons will remain adamant in their condemnation of this country. Find me a way out of this impasse, Mr. Fox, and I will bestow upon you the highest rewards this country can offer.”

“I wish that I could sir, how I wish that I could.”

BRINK OF WAR

Although it was the first day of May, it felt more like winter here in the northern hills of Vermont. Cold rain lashed the pine trees, turning the little-used track into adhesive mud. The horses walked slowly, heads down with weariness, and had to be urged on constantly by pulling on their reins. Both of the men who were leading them were as weary as the horses, yet they never for an instant thought of riding. That would have meant that their mounts would have to carry heavier loads. That was not possible. The reason for this long and exhausting journey was there in the barrels on the horses’ backs.

Jacques squinted up at the sky, then wiped his streaming face with the back of his hand. Only the rich could afford to buy a watch – and he was anything but that. But he knew by the steadily darkening sky that it was close to sunset.

“Soon, Phillipe, soon,” he shouted back in Canadian-accented French. “We will stop before we cross the ridge. Then go on after dark.”

His brother answered something, but his words were drowned out by a sharp crack of thunder. They plodded on, then turned from the track to seek some shelter under the branches of an ancient stand of oak trees. The horses found clumps of fresh grass to graze upon while the men slumped down with their backs against the thick trunks. Jacques took the cork from his water bottle and drank deep, smacking his lips as he sealed it again. It was filled with a strong mixture of whiskey and water. Phillipe watched this and frowned.

Jacques saw his expression and laughed aloud – revealing a mouthful of broken and blackened teeth. “You disapprove of my drinking, little brother. You should have been a priest. Then you could tell others what they should and should not do. It helps the fatigue and warms the bones.”

“And destroys the internal organs and the body.”

“That too, I am sure. But we must enjoy life as well as we can.”

Phillipe squeezed water from his thin, dark beard, and looked at the squat, strong body of his older brother. Just like their father. While he took after their mother, everyone said. He had never known her: she had died when he had been born.

“I don’t want to do this anymore,” Phillipe said. “It is dangerous – and some day we will be caught.”

“No we won’t. No one knows these hills as I do. Our good father, may he rest in peace with the angels, worked the stones of our farm until he died. I am sure that the endless toil killed him. Like the other farmers. But we have a choice, do we not? We can do this wonderful work to aid our neighbors. Remember – if you don’t do this – what will you do? You are like me, like the rest of us – an uneducated Quebecois. I can barely sign my name – I cannot read nor write.”

“But I can. You left school, the chance was there.”

“For you perhaps, I for one have no patience with the schoolroom. And if you remember our father was ill then. Someone had to work the farm. So you stayed in school and were educated. To what end? No one will hire you in the city, you have no skills – and you don’t even speak the filthy language of the English.”

“There is no need for English. Since the Act of Union Lower Canada has been recognized, our language is French – ”

“And our freedom is zero. We are a colony of the English, ruled by an English governor. Our legislature may sit in Montreal but it is the English Queen who has the power. So you can read, dear brother, and write as well. Where is the one who will hire you for these skills? It is your destiny that you must stay in Coaticook where there is nothing to do except farm the tired land – and drink strong whiskey to numb the pain of existence. Let the rest stay with the farming – and we will take care of the supplying of the other.”

He looked at the four barrels the horses were carrying and smiled his broken smile. Good Yankee whiskey, untaxed and purchased with gold. When they crossed back into Canada its value would double, so greedy were the English with their endless taxes. Oh yes, Her Majesty’s Customs men were active and eager enough, but they would never be woodsmen enough to catch a Dieumegard who had spent his life in these hills. He pressed his hand against the large outer pocket of his leather coat, felt the welcome outline of his pistol.

“Phillipe – ” he called out. “You have kept your powder dry?”

“Yes, of course, the gun is wrapped in oilskin. But I don’t like it…”

“You have to like it,” Jacques snarled. “It’s our lives that depend upon this whiskey – they shall not take it from us. That is why we need these guns. Nor shall they take me either. I would rather die here in the forest than rot in some English jail. We did not ask for this life or to be born in our miserable village. We have no choice so we must make the best of it.”

After this they were silent as day darkened slowly into night. The rain still fell, but not as heavily as earlier in the day.

“Time to go,” Jacques said, climbing stiffly to his feet. “One more hour and we will be across the border and in the hut. Nice and dry. Come on.”

He pulled on the horse’s reins and led the way. Phillipe leading the other horse, following their shapes barely visible in the darkness ahead.

There was no physical boundary between Canada and the United States here in the hills, no fence or marking. In daylight surveyors’ markers might be found, but not too easily. This track was used only by the animals, deer for the most part. And smugglers.

They crossed the low ridge and went slowly down the other side. The border was somewhere around here, no one was quite sure. Jacques stopped suddenly and cocked his head. Phillipe came up beside him.

“What is it?”

“Be quiet!” his brother whispered hoarsely. “There is something out there – I heard a noise.”

“Deer – ”

“Deer don’t rattle, crétin. There again, a clinking.”

Phillipe heard it too, but before he could speak dark forms loomed up before them. Mounted men.

“Merde! Customs – a patrol!”

Jacques cursed under his breath as he struggled his revolver from his pocket. His much-treasured Lefaucheaux caliber.41 pin-fire. He pointed it at the group ahead and pulled the trigger.

Again and again.

Stabs of flame in the darkness. One, two, three, four shots – before the inevitable misfire. He jammed the gun into his pocket, turned and ran, pulling the horse after him.

“Don’t stand there, you idiot. Back, we go back! They cannot follow us across the border. Even if they do we can get away from them. Then later get around them, use the other trail. It’s longer – but it will get us there.”

Slipping and tugging at the horses they made their way down the hill and vanished into the safety of the forest.

There was panic in the cavalry patrol. None of them had ventured into this part of the mountains before and the track was ill-marked. Heads down to escape the rain, no one had noticed when the corporal had missed the turning. By the time it grew dark they knew that they were lost. When they stopped to rest the horses, and stretch their legs, Jean-Louis approached the corporal who commanded the patrol.

“Marcel – are we lost?”

“Corporal Durand, that is what you must say.”

“Marcel, I have known you since you peed yourself in bed at night. Where are we?”

Durand’s shrug went unseen in the darkness. “I don’t know.”

“Then we must turn about and return the way we came. If we go on like this who knows where we will end up.”

After much shouted argument, name-calling and insults, they were all from the same village, the decision was made.

“Unless anyone knows a better route, we go back,” Corporal Durand said. “Mount up.”

They were milling about in the darkness when the firing began. The sudden flashes of fire unmanned them. Someone screamed and the panic grew worse. Their guns were wrapped about to keep them dry; there was no time to do anything.

“Ambush!”

“I am shot! Mother of God, they have shot me!”

This was too much. Uphill they fled, away from the gunfire. Corporal Durand could not stop them, rally them, not until the tired horses stumbled to a halt. He finally assembled most of them in the darkness, shouted loudly so the stragglers would find them.

“Who was shot?”

“It was Pierre who got it.”

“Pierre – where are you?”

“Here. My leg. A pain like fire.”

“We must bandage it. Get you to a doctor.”

The rain was ending and the moon could be seen dimly through the clouds. They were all countrymen and this was the only clue they needed to find their way back to camp. Exhausted and frightened they made their way down from the hills. Pierre’s dramatic moaning hurrying them on their way.

“Lieutenant, wake up sir. I’m sorry – but you must wake up.”

Lieutenant Saxby Athelstane did not like being disturbed. He was a heavy sleeper and difficult to waken at the best of times. At the worst of times, sodden with drink like this, it was next to impossible to stir him. But it had to be done. Sergeant Sleat was getting desperate. He pulled the officer into a sitting position, the blanket fell to the ground, and with a heave he swung him about so that the lieutenant’s feet were on the cold ground.

“Wha… what?” Athelstane said in a blurred voice. Shuddered and came awake and realized what was happening. “Take your sodding paws off of me! I’ll have you hung for this…”

Sleat stepped back, desperate, the words stumbling from his mouth as he rushed to explain.

“It’s them, sir, the Canadian militia patrol, they’re back…”

“What are you babbling about? Why in Hades should I care at this time of night?”

“They was shot at, Lieutenant. Shot at by the Yankees. One of them is wounded.”

Athelstane was wide-awake now. Struggling into his boots, grabbing at his jacket, then stumbling out of his tent into the driving rain. There was a lantern in the mess tent which was now crowded with gabbling men. A few of the volunteer militia could speak some broken English, the rest none at all. They were backwoods peasants and totally useless. He pushed through them, thrusting them aside, until he reached the mess table. One of their number was lying on the table, a filthy cloth tied about his leg.

“Will someone bloody well tell me what happened,” Athelstane snarled. Corporal Durand stepped forward, saluted clumsily.

“Eet was my patrol, sir, the one you ordered out that we should scout along the Yankee border. We rode as you told us to, but took too long. The weather it was very bad…”

“I don’t want the history of your sodding life – just tell me what you found.”

“We were at the border when it happened, many Yankees, they attacked suddenly, fired at us. Pierre here is wounded. We fought back, fired at them and drove them back. Then they went away, we came back here.”

“You say you were at the border – you are sure?”

“Sans doute! My men know this country well. We were very close to the border when the attack she came.”

“Inside Canada?”

“Oui.”

“You have no doubt that the bloody Yankees invaded this country?”

“No doubt, sir.”

Lieutenant Athelstane went to the wounded militiaman and unwrapped the rag from his leg; he groaned hoarsely. There was a bloody three-inch-long gash in his thigh.

“Shut your miserable mouth!” Athelstane shouted. “I’ve cut myself worse while shaving. Sergeant – get someone to wash this wound out and bandage it correctly. Then bring the corporal to my tent. We’ll see if we can’t make some kind of sense of this entire affair. I’ll take the report to the colonel myself.”

Lieutenant Athelstane actually smiled as he walked back through the lines. It would be jolly nice to get away from the frog militia for a bit, back in the mess with his friends. That was something to look forward to. He hadn’t bought this commission with his inheritance just to be buried out here in the forest. He would write a detailed report of this night’s business that would get the colonel’s attention and approval. Invasion from the United States. Cowardly attack. Fighting defense. It would be a very good report indeed. He would show them the kind of job he could do. Yes, indeed. This really was worth looking forward to.