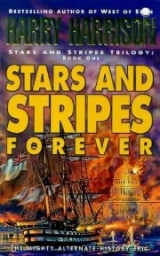

Текст книги "Stars and Stripes Forever"

Автор книги: Harry Harrison

Соавторы: Harry Harrison

Жанр:

Альтернативная история

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 15 (всего у книги 23 страниц)

SHARPSHOOTERS!

“The west flank, General – they’re coming over the wall!”

General Grant’s uniform was torn and dirty, his face black with smoke. He swayed in the saddle with fatigue; he had just returned from repelling another British attack. He pushed both hands down on the pommel of his McClellan saddle to straighten himself up.

“I want every second man from this line to follow me,” he ordered. “Let’s go boys! The way they been dying today they ain’t going to go on like this forever.”

He drew his sword and led the way, his exhausted horse barely able to stumble over the rough ground, beat down by the smoke and heat. And there they were, dark-green uniformed soldiers with black buttons, a fresh regiment thrown into battle. General Grant drew his sword and shouted wordless encouragement as he led the attack.

He avoided the bayonet, kicked it aside with his stirruped heel, then leaned over to slash the man across the face. His horse stumbled and fell, and he dragged himself clear. The melee was hand-to-hand and a very close run thing. Had he not brought his relief troops the battery and revetments would have been taken, punching a hole in the line they were fighting so hard to defend.

When the last green-uniformed attacker had been killed, his body dumped unceremoniously over the wall, the American forces still held the line. Battered, exhausted, filthy beyond belief, with more dead than living: they had held.

And that is the way the day went. The enemy, as tired as they were, kept attacking uphill with grinding strength. And were repelled with only the greatest of effort. Grant had said that his line would not break and it did not.

But at what a terrible cost.

Men who were wounded, bandaged, went back to fight again. Used their bayonets lying down when they were too fatigued to stand. It was a day for heroism. And a day for death. Not until it began to grow dark did the defenders realize that this day of hell was over. And that they had survived, fewer and fewer, but enough to still fight on.

The firing died away at dusk. Visibility faded in the gathering darkness, made even more obscure by the hovering clouds of smoke. The British had withdrawn after their last desperate attack, leaving behind the tumbled redcoat corpses on the ridge. But for the exhausted American survivors of the daylong attack there could be no rest, not yet. They lay aside their muskets and seized up spades to rebuild their defensive earthworks where British shells had torn great gaps. Boulders were rolled up and heaved into position. It was well past midnight before the defenses were up to Grant’s expectations. Now the weary soldiers slept where they fell, clutching their weapons, getting what rest they could before dawn saw the British attacking yet one more time.

General Grant did not rest, could not. Trailed by his stumbling aide-de-camp he went from one end of the defenses to the other. Saw that ammunition was ready for the few cannon remaining, that food and water were brought up from the rear. He looked into the charnel house of the field hospital with the pile of dismembered arms and legs beside it. Only when all had been done that could be done did he permit himself to drop into the chair before his tent. He accepted a cup of coffee and sipped at it.

“This has been a very long day,” he said, and Captain Craig shook his head at the understatement.

“More than long, General, ferocious. Those British know how to press home the attack.”

“And our boys know how to fight, Bob, don’t you forget that. Fight and die. Our losses are too heavy. Another attack like this last and they could break through.”

“Then in the morning…?”

Grant did not answer but drank his coffee – then looked up sharply at the distant sound of a train’s whistle.

“Is the track still open?”

“Was a couple of hours ago. I had a handcar run back down the line to check it. Telegraph wire is still out of service though. It seems that either the Brits don’t have their cavalry out behind us or they just don’t know the military value of the train.”

“May they never learn!”

There was the scrabble of running feet and a soldier appeared in the firelight, throwing a ramshackle salute.

“Train comin’ into the siding, General. Captain said you would shore like to know.”

“I shore do. Troops.”

“Yes, sir.”

“About time. Captain Craig, go back with this man. Get the commanding officer and bring him to me while they are unloading.”

Exhausted but still not able to sleep, Grant took more coffee and thought about the stone crock of whiskey in the tent. Then forgot about it. His days of drowning troubles that way were long past; he could face them now. He frowned as he noticed that the sky was growing bright, relaxed only when he realized that it was the newly risen moon. Dawn was still some hours away.

Footsteps sounded in the darkness – and a sudden crash and a guttural curse as one of the approaching men tripped. Then Captain Craig appeared followed by a tall, blond officer who limped slightly and brushed at his uniform. He was an amazing sight among the battle-stained survivors with their ragged uniforms. The newcomer was bandbox perfect with his stylish green jacket and light blue trousers, while the rifle he carried was long and elaborately constructed. When he saw Grant he stopped and saluted.

“Lieutenant Colonel Trepp, General. 1st Regiment United States Sharp Shooters.” He spoke with a thick German accent. Grant coughed and spat into the fire. He had heard of these Green Coats but had never had any of them under his command.

“What other regiments are with you?”

“None that I know of, General. Joost my men. But there is another train running a few minutes behind us.”

“A single regiment! Is that all I am sent to hold back the entire British army? Carnival soldiers with outlandish guns.” He looked at the strange weapon that the officer was carrying. Trepp fought hard to keep his temper.

“Dis is a breech-loading Sharps rifle, General. With rifled barrel, double trigger and telescopic sight – ”

“All that isn’t worth diddily-squat against an enemy with heavy guns.”

Trepp’s anger faded as quickly as it had come. “In that you are wrong, sir,” he said quietly. “You watch in the morning what we do against them guns. Just show me where they are, you don’t worry. I am a professional soldier for many years, first in Switzerland then here. My men are professional too and they do not miss.”

“I’ll put them in the front line and we’ll see what they can do.”

“You will be very, very happy, General Grant, that you can be sure of.”

The sharpshooters filtered out of the darkness and worked their way down the battlements. Only when they were gone did a waiting soldier approach Grant. When he was close to the fire Grant saw by his uniform that he was an infantry officer.

“Captain Lamson,” he said, saluting smartly. “3rd Regiment USCT, sir. The men will be unloading soon – we had to wait until the train ahead of us was moved out. I came ahead to let you know that we are here.”

Grant returned the salute. “And very grateful I am. You and your troops are more than welcome, Captain Lamson. What did you say your unit was?”

“Sergeant Delany, step forward please,” Lamson called out and a big sergeant stepped into the firelight. He had a first sergeant’s stripes on his sleeves and saluted with all the vigor and correctness of that rank.

Grant automatically returned the salute – then paused, his hand half raised to his hat brim.

The sergeant was a Negro.

“Second Regiment USCT reporting for duty,” he called out in best drillfield manner. “Second Regiment United States Colored Troops.”

Grant’s hand slowly fell to his side as he turned to the white officer. “You can explain?”

“Yes, General. This regiment was organized in New York City. They are all free men, all volunteers. We have only been training a few weeks – but were ordered here as the nearest troops available.”

“Can they fight?” Grant asked.

“They can shoot, they have had the training.”

“That is not what I asked, Captain.”

Captain Lamson hesitated, turning his head slightly so that the firelight glinted from his steel-rimmed spectacles. It was Sergeant Delany who spoke before he did.

“We can fight, General. Die if we have to. Just put us into the line and face us toward the enemy.”

There was a calm assurance in his voice that impressed Grant. If the rest were like him – then he could believe it.

“I hope that you are right,” he said. “They will have the opportunity to prove their worth. We will certainly find out in the morning. Dismissed.”

Grant realized that he meant the words most strongly. Right now he would put a regiment of red Indians – or red devils for that matter – into the battle against the British.

The enemy lines had been reinforced during the night. The pickets reported hearing horses and the sound of rattling chains. At first light Grant, who had fallen asleep in his chair stirred and woke. Yawning deeply he splashed cold water onto his face, then climbed to the parapet and trained his field glasses on the enemy lines. Before them, on the right flank, a battery of artillery was galloping up in a cloud of dust. Nine-pounders from the look of them. Grant lowered his glasses and scowled. He had used the 1st Regiment USCT to fill in the gaps where his line was the weakest. Colonel Trepp had stationed his men at intervals along the defense positions and he was waiting close by for instructions. Grant pointed at the distant guns.

“You still believe that you can do anything against weapons like that?”

Trepp shaded his eyes and nodded. “That will not be a problem, General. Impossible of course without the right training and the right weapon. For me, I do not exaggerate when I tell you that it is a very easy shot. I make it to be just 230 yards.” He lay prone and settled the gun butt against his shoulder, squinted through the telescopic sight.

“It is still too dark and we must be patient.” He spread his legs apart for a more comfortable position, then looked again through the telescopic sight. “Yes, now, there is enough light.”

He slowly pulled down the long trigger that cocked the smaller hair-trigger. Took careful aim and gently touched the trigger. The gun barked loudly and pounded into Trepp’s shoulder.

Grant raised his glasses to see the officer commanding the battery rear up. Clutch his chest and collapse.

“Sharp Shooters – fire at will,” the colonel ordered.

It was a slow, steady roll of fire as the sharpshooters who lay prone behind the battlement fired, opened their rifle breeches to load bullets and linen cartridges, sealed and fired again.

In the British line the gunners were unfastening the trails of their guns from the limbers, wheeling them about into firing position. While they did this they died, one by one. Within three minutes all of them were down. Next were the horse holders, killed as they tried to flee. And finally, one by one, the patient horses were killed. It was butchery, the best butchery that Grant had ever seen. Then a British gun fired and the shell screamed by close overhead. Grant pointed.

“Easy enough when they’re out in the open. But what about that? An entrenched and sandbagged gun. All you can see is the muzzle.”

Trepp rose and dusted off his uniform. “That is all we need to see. That gun,” he ordered his men, “take it out.”

Grant looked through his glasses as the reloaded gun in the center of the British lines was run back into firing position. Bullets from the sharpshooters began to hit in the sand all about the black disk of the muzzle and spurts of sand almost obscured it; then it fired again. When it was reloaded and run back into position yet again the bullets tore into the sand around the muzzle.

This time when the cannon fired it exploded. Grant could see the smoking wreck and the dead gunners.

“I developed this technique myself,” Trepp said proudly. “We fire most accurately a very heavy bullet. There is soon enough sand in the barrel to jam the shell so that it explodes before leaving the muzzle. Soon when the attack begins we will show you how we handle that as well.”

“Truthfully, Colonel Trepp, I am greatly anticipating seeing what you get up to next.”

The destruction of the artillery seemed to have impressed the enemy commander, because the expected attack did not come at once. Then there was sudden movement on the far left flank as another battery of guns was pulled into position. But Trepp had stationed his sharpshooters in small firing units the length of the line. Within minutes the second battery had met the same fate as the first.

The sun was high in the sky before the expected move came. To the rear of the enemy lines a small party of mounted officers trotted out from the distant line of trees. They were a good five, perhaps even six hundred yards away. There was a ripple of fire from the American positions and Grant called out angrily.

“Cease firing and save your ammunition. They are well out of range.”

Trepp was speaking to his marksmen in German and there was easy laughter. The colonel aimed carefully then said softly, “Fertig machen?” There was an answering murmur as he cocked the first long trigger. “Feuer,” he said and the guns fired as one.

It was as though a strong wind had swept across the group of horsemen, sweeping them all from their saddles in a single instant. They sprawled on the ground while their startled mounts quieted, lowered their heads and began to graze.

A single gold-braided, scarlet-coated figure started to rise. Trepp’s rifle cracked and he dropped back among the others.

“I always take the commanding officer,” Trepp said, “because I am the best shot. The others take from left to right as they wish and we fire together. Good, Ja?”

“Good, Ja, my friend. Are your marksmen all Swiss?”

“One, two maybe. Prussian, Austrian, all from the old countries. Hunters there, damn good. We got plenty Americans too, more hunters. But these boys the best, my friends. Now watch when the attack comes. We shoot officers and sergeants first, then the men carrying the little flags, then the ones who stop to pick up flags. They always do that, always get killed. Then we shoot the men who stop to shoot at us. All this before their muskets are within range. Lots of fun, you will see.”

Despite losing many of their officers the British pushed the charge home, roaring aloud as they rushed the last yards. Most of the troops on both sides had fired their final rounds and the battle was joined with bare bayonets. Grant looked at his new colored troops and found them holding the line, fighting fiercely, then even pursuing the attacking redcoats when the charge lost its momentum. Fight and die their sergeant had said – and they were doing just that.

Perhaps this battle was not lost quite yet, Grant thought.

The little steamer, River Queen, that had been so empty on the outward bound trip from Washington, was as filled as a Sunday excursion boat on her return voyage. Jefferson Davis, Robert E. Lee and all their aides filled the salon. The air was thick with the smoke of cigars and excited talk: there was good attendance in an alcove where a keg of whiskey had made an appearance. Abraham Lincoln retreated to a cabin with his secretaries, and General Sherman, to write the first of the many orders that must be issued. General Lee was called to consult with them and the atmosphere here became so close after a bit that Lincoln retreated to the deck where the air was fresher. The ship slowed as they approached the harbor at Yorktown where General Pope and his staff were waiting. Soon their blue uniforms were mixing with the gray of Lee’s officers. All of these men had served together at one time and knew each other well. Now they put the war behind them. Men who had been separated by the conflict were comrades once again. Seeing the President standing alone, General John Pope left the others and went to join him.

“The best of news, Mr. President. The telegraph line is finally opened to Grant’s command. They have held!”

“Welcome news, indeed John.”

“But they held at a terrible price. He reports at least 16,000 dead, more wounded. The reinforcements are getting through to him, the regiment of sharpshooters was first, then the New York Third. More are on the way. As soon as the cease-fire with the Confederates went into effect almost all the troops from the Washington defenses were pulled out and sent north. The first of them should be reaching Grant later today. I have another division on the way. We are getting plenty of men to the railheads, that is not the problem. Trains are. Just not enough available to move all the men that are needed.”

“You keep at it. Any problems with the railroads, let me know. We will see what kind of pressure we can apply. Grant must have all the reinforcements available – and he must hold until our joint forces can relieve him.”

“General Grant sent you a personal report on the fighting. With an added note to the army. He wants more troops like the New York Third.”

“He does? Now tell me – what is so special about them?”

“They are Negroes, Mr. President. We have other black regiments in training – but this is the first to have seen battle.”

“And their behavior under fire?”

“Exemplary according to Grant.”

“This war of invasion seems to be changing the world in many and unusual ways.”

The water became more choppy as the steamer left the York River and headed northeast into Chesapeake Bay, toward the mouth of the Potomac River. These were busy waters and at least two other ships could be seen close by. Low on the eastern horizon were even more ships, white sails and smears of black smoke against the blue sky. Lincoln pointed them out.

“More of the blockading fleet being withdrawn, I imagine.”

“They would not have received their orders yet,” General Pope said. “Only those in port that could be reached by telegraph.” He signaled to an aide to bring his telescope, raised it to his eye.

“Damnation!” he said. “Those aren’t American ships. Union Jacks – I can see them! That is a British fleet!”

“Which way are they going?” Lincoln called out, feeling a dreadful anticipation. “Send for the captain.”

The ship’s first officer came down from the bridge and saluted. “Captain’s compliments, Mr. President, but he would like to know what he should do. Those are British warships.”

“We know – but we don’t know which way they are going.”

“Same heading as ours, the mouth of the Potomac River. Towards Washington City. All but one of them.

“One of the battleships has altered course and is coming our way.”

PRESIDENTS IN PERIL

There was a feeling of tension released, and even pleasure and happiness, in Whitehall as they went through the reports that the packet had brought from Canada to Southampton.

“I say,” Lord Palmerston called out, waving a paper in the air. “General Champion reports that the Yankees appear to be putting up only the poorest of defenses. Plattsburgh taken and the troops marching on, advancing steadily. Jolly good!” And his gout had eased as well; the world had become a sunnier and more beneficent place.

“And this from the admiralty,” Lord Russell said. “The fleet in the Gulf Coast attack should have completed their task by now. They are expecting the first reports of victory very soon. From the Washington City attack as well. The navy showed great foresight and tactical acumen there. I must say that the Admiralty has more imagination and tactical ability than I ever gave them credit for. Perfectly timed. Waited until the reports came in that troops were being pulled out of the defenses of the capital. Then, while the American soldiers rush to defend their borders – attack the heart of their homeland. They will soon be brought to heel.”

Palmerston nodded in happy agreement. “I do agree. And I know that I can confide in you, John, that at times I have been a bit worried. It is one thing to talk about war – another thing completely to take the first step and open battle. I like to think that I am a peaceable man. But I am also an Englishman and will not suffer in silence when insulted. And this fair land has been insulted, gravely, gravely. And then there is the fact that Wellington was so positive that we should not go ahead with the war. That worried me. But, still we pressed on. But now, by hindsight, I can see that this war has all been right and proper, almost preordained.”

“In truth, I am forced to agree. I look forward to the next reports with utmost expectation.”

“As I do, old friend, as I do. Now – I must to Windsor to bring these good tidings to the Queen. I know that she will share our pleasure at the good news. Preordained, preordained.”

Captain Richard Dalton, 1st U.S. Cavalry, had not seen his family in over a year. If he had not been wounded at the battle of Ball’s Bluff he might have gone another year without getting home. The piece of shrapnel that had lodged in his right shoulder hurt bad enough, hurt even more when the surgeon cut it out. He could still ride pretty well, but it would be some time before he could raise a sword or fire a gun. His CO. had been willing to grant him sick leave so, despite the almost constant pain, he felt himself a lucky man. He was still alive when a lot of his men were not. The ride south from the capital was an easy one, his welcome when he opened his front door worth all the pain past, pain to come. Now the sun was warm, the fish were biting, he and his seven-year-old son had almost filled the creel in a few hours.

“Daddy – look at our ships! Ain’t they great?”

Dalton, almost dozing in the warm sunlight, looked up at the mouth of the inlet where it met the Potomac.

“Sure big ones, Andy.” Ships of the line, hurrying upstream under sail and steam. White sails filled, black smoke roiling from their funnels. It was a grand sight indeed.

Until a puff of wind caught the flag on the stern of the third vessel in line, spread it out before flapping it about the staff again.

Two crosses, one over the other.

“The Union Jack! Row for shore Andy, just as fast as you can. Those aren’t our ships, not by a long sight.”

Dalton jumped onto the bank as soon as the bow grated on the sand, bent to tie it up one-handed.

“Go on Andy. I’ll bring the fish – you just run up to the barn and saddle up Juniper.”

The boy was off like a shot, along the lane that led to their house at Piney Point. Dalton secured the boat, then grabbed up the fish and followed him, found Marianne waiting at the back door, looking troubled.

“Andy shouted something about ships – then ran into the barn.”

“I’ve got to ride to the depot in Lexington Park, they have a telegraph there. Got to warn Washington City. We saw them. British warships, an awful lot of them, heading upriver toward Washington. Got to warn them.”

The boy led the big gray out. Dalton checked the tightness of the girth, smiled and tousled the lad’s hair. Grabbed the pommel with his left hand and swung himself up into the saddle.

“I’ll be back as soon as I can. Soon as I tell them that the war is on its way to the capital.”

Mary Todd Lincoln laughed aloud with happiness as she poured the tea. Cousin Lizzie, who was new to Washington, was not impressed by the local ladies and was so funny when she strutted across the room, flouncing an invisible bustle.

“Why I tell you – I am not making this up. They just don’t have style. You don’t see ladies in Springfield or Lexington walking like that – or talking like that.”

“I don’t think that this is a real Southern city,” Mary’s sister, Mrs. Edwards said. “I don’t think it knows what it is, what with all those Yankees and politicians infesting the place.” She took the cup of tea from Mary. “And, of course, none of them are Todds.”

The sisters and cousins and second-cousins all nodded at this. They were a close-knit family and it was Mary’s pleasure to have them visiting her. Just for a change the talk of the war was taking second place to gossip.

“I am so afraid for Mr. Lincoln and this mysterious meeting that no one will tell us about,” Cousin Amanda said. “An Abolitionist going into the deep South at this time!”

“You mustn’t believe everything you read in the vampire press,” Mary said firmly. “They are always after me as being pro-Southern and pro-slavery when y’all know the truth. Of course our family kept slaves, but we never bought them or sold them. You all know my feelings. The first time I saw a slave auction, saw them being whipped – why I became as much of an abolitionist as a Maine preacher. I’ve always felt that way. But Mr. Lincoln, the thought of his being an abolitionist is so absurd. I don’t think he knew anything about slavery until he visited me at home. And he has the strangest idea about slaves. Thinks that if you bundle them all off to South America that would solve the problem. He is a good man but not knowledgeable about the Negro. But he does want to do the right thing. What he believes in – is the Union, of course. And justice.”

“And God,” Cousin Lizzie asked, a twinkle in her eye. “I do believe that I haven’t seen him in church at all during this visit.”

“He’s a busy man. You can believe in God without going to church. And vice versa, I must say. Have some more tea? Though some argue with that.” Mary smiled, sipped her tea and sat back.

“Now you didn’t know him when he first ran for Congress because that was many years ago. The man running against him for the office was a hellfire and brimstone Methodist preacher who always tried to make out that Mr. Lincoln was an infidel. Then one day he saw his chance when he was preaching in church and Mr. Lincoln came in and sat in the back. The preacher knew what he had to do and he called out ‘All of you who think you are going to Heaven, you rise.’ There was a bustle as most of the congregation got up. Mr. Lincoln did not stir. Then the preacher asked for all those who expected to go to Hell to stand. Mr. Lincoln did not stand. This was the preacher’s chance.

“ ‘So then, Mr. Lincoln – where do you think you are going?’

“Only then did Mr. Lincoln stand up and say, ‘Well – I expect to go to Congress.’ And he left.”

Most of them had heard the story before, but they still laughed. The tea was nice, the little cakes sweet, and the gossip even sweeter.

There was a sharp knock at the door of the Green Room and it was thrown open.

“Mother, I must tell you – ”

“Robert, such a hurry, that’s not like you.” Her son was down from Harvard for a few days; no longer a boy, she thought. He had filled out during the year that he had been away.

There was more than one giggle and he flushed. “Mother, ladies, I am sorry to burst in like this. But you must all leave the Presidential Mansion at once.”

“Whatever do you mean?” Mary asked.

“The British, they are coming, they are attacking the city.”

Mary did not drop the teapot, but forced herself to set it down gently instead. A lieutenant ran in through the open door.

“Mrs. Lincoln, ladies, we got a telegraph, they were sighted in the river, they are coming! The British – a flotilla, coming up the Potomac.”

There was silence. The words were clear – but what did they mean? British ships in the Potomac and moving on the nation’s capital. There were hurrying footsteps in the hall and Secretary of War Stanton pushed in; he must have rushed over from the War Department building just across the road.

“You have heard, Mrs. Lincoln. The British are on their way. I blame myself for not thinking of this – someone should have. After their attack from the north we should have seen history repeating itself. We should have realized, thought more about 1812, they seem to fight their wars in a most predictable way.”

Mary suddenly realized what he was talking about. “They attacked Washington then, burnt the White House!”

“They did indeed and I am sure that they intend to repeat that reprehensible deed yet again. You must get your son down here at once. We should have a little time yet, pack some light bags…”

“I’ll fetch my brother,” Robert said. “You get the ladies moving.”

She was too disturbed to think straight. “You want us to flee? Why? Mr. Lincoln has reassured me many a time about the defenses that guard this city from attack.”

“Did guard, I am most unhappy to say. With the onset of the cease-fire we felt that they could be withdrawn, sent to the aid of General Grant. I blame myself, for I of all people should have considered all of the consequences, that is my duty. But like all the others I thought only of the fate of Grant and his troops. Almost all of the Washington garrison is now on its way north. Even the Potomac forts are undermanned.”

“Recall them!”

“Of course. That is being done. But time, it takes time. And the British are coming. Gather your things, ladies, I beg of you. I will arrange for carriages.”

Stanton hurried out past the waiting officer who turned to Mrs. Lincoln again. “I’ll send some troopers to help you, ma’am, if that’s all right.”

“Come, Mary, we have things to do,” Cousin Lizzie said.

Mary Lincoln could not move. It was all too sudden, too shocking. And she felt one of her headaches coming on, the big ones that put her to bed in a darkened room. She closed her eyes and tried to will it away. Not now, not at this time.

“Stay here a moment,” Mrs. Edwards said, putting a protective arm about her sister. “I’ll get Keckley, Robert is fetching Tad. I’ll have her bring the bags right down here. Then we’ll think about packing some things. Lieutenant – how much time do we have?”

“One, maybe two hours at the most before they get here. No one seems to rightly know. I think it’s best we get going now.”

Robert led Tad in; the boy ran to his mother and put his arms around her. Mary hugged him back, felt better for it. Keckley, more of a friend now than the Negro seamstress they had hired, looked concerned.

“We have some time,” Mary said. “To get away from the White House before the British arrive. Help the ladies pack some clothes for a few days.”

“Where will we go, Mrs. Lincoln?”

“Give me a moment to think about that. Please, the bags.”