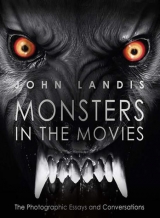

Текст книги "Monsters in the Movies "

Автор книги: Джон Лэндис

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Re-Animator [Stuart Gordon, 1985]

Poster for Re-Animator.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Frankenstein’s monster [Mary Shelley, 1831]

Frontispiece illustration from the 1831 edition of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheusby Mary Shelley.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde [Rouben Mamoulian, 1931]

Fredric March’s Dr. Jekyll transforms into Mr. Hyde. March won a Best Actor Academy Award for this performance.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

The Curse of Frankenstein [Terence Fisher, 1957]

Peter Cushing as the ruthless and cold Dr. Frankenstein with Christopher Lee as the victimized monster.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

The Bride of Frankenstein [James Whale, 1935]

Elsa Lanchester as the mate Frankenstein has made for his monster.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Ernest Thesiger, as Dr. Pretorius, displays his own creations—homunculi he keeps in jars!

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Forbidden Planet [Fred M. Wilcox, 1956]

Walter Pidgeon as Dr. Edward Morbius, a scientist who has partially solved the remarkable secrets of the Krell, a vanished alien race.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Die, Monster, Die! [Daniel Haller, 1965]

A stunt man doubles for Boris Karloff as the unfortunate victim of radiation from a meteorite in this movie based on H. P. Lovecraft’s story The Color Out of Space[1927].

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

The Invisible Man [James Whale, 1933]

Claude Rains made his film debut in a role in which he was not seen but heard. Whale treated the story as a comedy, while Rains gave full throat to his character’s growing megalomania. With groundbreaking special effects by John P. Fulton.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Island of Lost Souls [Erle C. Kenton, 1932]

A rare photograph of a test make-up. A remarkable mixture of animal parts in a terrific design not seen in the finished film.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Charles Laughton gives a fantastic performance as the sadistic Dr. Moreau. Here, he gives instructions to one of his Beast Men.

“We are not men! We are not beasts! We are things!”

The Sayer of the Law (Béla Lugosi), Island of Lost Souls

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Boris Karloff, Colin Clive [ Frankenstein, James Whale, 1931]

The monster (pictured first) and his maker (pictured second) in the first of the three films in which Karloff played the role.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

The Fly [Kurt Neumann, 1958]

Herbert Marshall, Vincent Price, and Charles Herbert discover the terrible truth in the horrifying climax of The Fly.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

The Fly [David Cronenberg, 1986]

Jeff Goldblum as mad scientist Seth Brundle in two stages of his metamorphosis into what he terms “Brundlefly.” Cronenberg’s movie is both gross and emotionally powerful.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Jeff Goldblum as mad scientist Seth Brundle.

“I’m an insect who dreamed he was a man and loved it. But now the dream is over… and the insect is awake. ”

Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum), The Fly

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes [Roger Corman, 1963]

Ray Milland is Dr. James Xavier, whose experimental eyedrops allow him to see more than the human eye should. Once again, the moral is that we should not tamper with the natural order of things. Xavier ends up tearing out his own eyes! One of Corman’s best films, with a terrific performance from Don Rickles as a carnival barker who sees a way to profit from Xavier’s affliction.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Swamp Thing [Wes Craven, 1982]

Dick Durock as Swamp Thing in the first film based on the DC Comic book character. Durock wore this suit in a sequel and the subsequent television series. As H. L. Menken said, “No one ever went broke underestimating the American public.”

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

Sssssss [Bernard L. Kowalski, 1973]

Mad ophiologist Dr. Stoner (Strother Martin) injects snake venom into his daughter’s boyfriend, which transforms him into a malformed, half-man, half-snake.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

The Incredible 2-Headed Transplant [Anthony M. Lanza, 1971]

A drive-in classic, in which mad doctor Bruce Dern transplants the head of a criminal onto the body of a big, mentally handicapped guy. Essentially remade as The Thing With Two Heads[Lee Frost, 1972], in which racist Ray Milland’s head is attached to African American Roosevelt Grier’s body, to Rosey’s head’s dismay. The Thing With Two Headsboasts an early cameo by Rick Baker in a two-headed gorilla suit.

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

The Brain That Wouldn’t Die [Joseph Green, 1962]

Dr. Bill Cortner (Jason Evers) attends to the head of his fiancée (Virginia Leith). He keeps her head alive in his basement while he searches for a voluptuous body to replace the one she lost in a car accident! An outrageous movie with a deeply twisted premise.

IN CONVERSATION

David Cronenberg

“Directing a movie is similar, in some ways, to a science experiment.”

David Cronenberg on the set of A History of Violence[2005].

Mad Scientists[ Book Contents]

JL: David, how would you define a monster?

DC: A monster is a distortion of something that has a normal, non-threatening form. The monstrous form is threatening and disturbing because it is beyond the pale of what we consider normality. A monster is a deformation of what we consider normal and therefore safe.

JL: Do you remember your first encounter with a monster movie?

DC: Bambi[James Algar, Samuel Armstrong, 1942] was scary, and in Bambiit’s the humans who are the monsters. As a kid I identified with Bambi. The hunters who would kill your mother are definitely monsters!

JL: What about the classic monsters like Frankenstein, Dracula, the Wolf Man?

DC: All those guys are deformations of normal humanity. Those are probably the scariest kind of monsters. But the shark in Jaws[Steven Spielberg, 1975] isn’t a monster. It’s an animal designed to kill you. It has no expression, its eyes are dead eyes. It is a killing machine. Does it qualify as a monster? Not really. Same with a T-Rex.

JL: What about Godzilla or a Cyclops or a dragon?

DC: Well, those are different because a Cyclops is a deformation of the human form. And there are some great monstrous creatures in, let’s say, some of the Harry Potterfilms that are based on a Tyrannosaurus rex.

JL: But those dragons are magic!

DC: I think the further away from the human form a monster becomes, the more it becomes like a natural disaster. So, if you’re eaten by a shark, it’s almost like being hit by lightning. There’s no ill will there. It’s just a machine-like animal behaving normally. A natural occurrence.

JL: In Jaws, they did give the shark a personality. They made it malevolent.

DC: That’s true… that was an attempt to mythologize the shark. To make the shark more than just a killing machine. And that’s why Jawswas more successful than the movies about hundreds of piranhas who eat you up. The fact that there was one shark was the key. That’s sort of a Moby Dick thing, to humanize and then mythologize an animal. When a monster is recognizably human, like a Cyclops, that’s when the definition of monster and monstrous and monstrosity becomes very specific and very resonant.

JL: Okay. The Frankenstein Monster and the Wolf Man—I always find them sympathetic because they’re victims.

DC: Yeah, there is a wonderful layering of those characters that makes them much more interesting. The same with vampires—there’s just endless vampire films happening right now! But the more vampires are humanized, and even made beautiful, like in the Twilightmovies, there comes a point where you treat them like… the disabled or something. They’re humans but they have this disease problem. In other words, I guess you can go too far with the empathy. There has to be that sense of danger for a monster to really be a serious monster.

JL: What about the new craze for zombies? The flesh-eating, walking dead. What’s that about?

DC: I think that’s about video games, frankly. But once again they are deformations of normal humans and not only in the way they look, but also in their craving for human flesh.

JL: What do you mean by video games?

DC: In the early days of video games, the way that you could get around parental fear of having children enjoying killing people, was to have them not be people exactly. If they’re anonymous creatures, it’s okay to kill them. And really part of the fun of those movies and TV series is just the many different ways that you can kill a zombie. You don’t have empathy with them, they’re not sympathetic… everything shifts to sort of, like, “slaughter fun.” It’s actually quite different from the vampire thing.

JL: What are your thoughts on the Devil or demons or satanic possession?

DC: I have big problems with demons and the devil, since I don’t believe in them. So, I’ve never dealt with anything like that in any of my films.

JL: A movie is supposed to create suspension of disbelief. I am an atheist; I am a Jew; I do not believe in Christ or the devil but, when I saw The Exorcist[William Friedkin,1973] in the theater, it scared the shit out of me.

DC: The Exorcistwas scary. It was very effective.

JL: Because it…

DC: Because it created a world that seemed real to you and they had a couple of priests in it who were characters you could identify with. The audience wants to be in the film, you know. If you haven’t been able to make use of that desire as a filmmaker then you’ve failed. Because audiences come to the movies wanting that and if you shut them out of your movie, well, it’s your fault. If you bring them into it, then, yes, you can absolutely create an ambience that is convincing. For the time of the movie the audience is living in that universe. And in that universe anything is possible. The Exorcistfelt absolutely real and it drew you in slowly, slowly, before it started to hit you over the head. So, it was a very interesting example of suspension of disbelief.

JL: What drew you to The Fly[1986]? It’s really about a mad scientist.

DC: I studied organic chemistry at the University of Toronto and I thought that I might be able to be like Isaac Asimov, a scientist and a writer. The fact that The Flywas based on some interesting and then-current hard science was what appealed to me. It wasn’t magic. It wasn’t supernatural. It was very physical. It was very body-oriented. And as an atheist, existentialist Jew myself, I really do think that the body is what we are, and that religion is a flight from that, fear of that…

JL: A lot of your movies deal with the human body…

DC: That’s right.

JL: I thought that what happens to Jeff in The Flywas like a form of cancer. In fact, in a lot of your pictures, there are projections of cancer and aging…

DC: Yes, but isn’t that intriguing? I mean, as you and I grow older, you can see what happens when someone, someone perhaps close to you, becomes monstrous. Monstrous in the sense that their body transforms as they age. And their mind, perhaps, starts to go in unpleasant ways. That’s close-to-home monstrousness. The more fantastical a movie is, and I include demons and stuff, the further away it is from your body, from human reality.

JL: I saw The Exorcistwith George Folsey, Jr. and Jim O’Rourke, who had been altar boys, both lapsed Catholics. It scared me, but when it was over I went home and went to sleep. Jim and George had nightmares for weeks!

DC: So, with The Fly, although you’re not a scientist and you didn’t go through the telepod, you are human and you have seen people become diseased or heard about people aging too rapidly or dying too soon. Any human in any culture can relate to what happens to the Jeff Goldblum character Seth Brundle in The Fly…

JL: So you don’t consider him a mad scientist?

DC: No, not at all. Not at all mad. I have read fairly deeply into scientists and their life stories… They are a strange breed, but they’re very human, and they’re not mad at all. They’re risk takers. I think most filmmakers can relate to scientists because we work with technology to create things that didn’t exist before, to explore the world as we find it. Directing a movie is similar, in some ways, to a science experiment.

JL: It seems to me that all of the mad scientists and mad doctors in movies tend to illustrate the falsehood, “There are things Man is not meant to know.” And you don’t fuck with God’s work. These films tend to be very conservative and reactionary and, although I hardly think of you as conservative or reactionary, all of the scientists in your films do end badly.

DC: Well, there’s a reason for that. As George Bernard Shaw said: “Conflict is the essence of drama.” It’s dramatic compulsion that makes me do it. It wasn’t God who made me do it!

JL: But the protagonists in your films do follow in the tradition of the scientist messing with “things he should not know.”

DC: But you see it is the things that he mustknow. That’s quite different…

JL: But in your films the “things he must know” end in violence and death.

DC: Yeah. Because it would not be very interesting if it didn’t. That’s what I mean by dramatic compulsion. It’s to make it interesting and compelling for the audience.

JL: I don’t think…

DC: Yes, there’s a kind of an arrogance involved, but there’s also a real desire to get to grips with the essence of human existence and the physical existence of Man and how that relates to the human spirit and to the human mind. My approach is more like William Burroughs’, that is to say, “Art is dangerous.” Creation is a dangerous thing, but we must do it. We are compelled to do it. It is in the nature of Man to be creative. We transformed the planet as we evolved as human creatures. You don’t stay out in the rain, you find shelter; you don’t accept cold, you build a fire. Immediately you are not accepting the world as it is. To me that’s just basic human activity. When you put this in a dramatic, scary but interesting context, you often end up with the scientist in a bad place because, in fact, a lot of scientists do end up in a bad place. Like the astronauts killed in the Space Shuttle explosion. Scientists are aware of the potential danger of exploring the things that they explore, but they feel an incredible compulsion to do so—a creative compulsion and a desire for knowledge to understand the world. My movies often examine the price that is paid for that. But they’re not really cautionary tales.

JL: Yes they are, David! Regardless of your intent, they are cautionary tales because they always end badly.

DC: Every medical discovery in the world has killed somebody, often a researcher or scientist…

JL: What’s interesting about your version of The Flyis how attractive and funny and intelligent Goldblum’s character is.

DC: There are many scientists who have suffered some disease by making themselves their own subject. And a way of distancing yourself from this terrible affliction that’s hit you is to examine it like a scientist. To examine yourself as though you’re your own patient or your own specimen.

David Cronenberg with the star of The Fly[1986].

JL: Why do we like horror films?

DC: I think it’s a rehearsal for dealing with death…

JL: But that’s what a rollercoaster is. A rollercoaster allows you to feel…

DC: No, no, I don’t agree. You’re talking to someone who has raced cars and motorcycles. Of course there’s an element of “Oh my god I’m going to die,”—a good rollercoaster will give you that. And there’s also the incredible sensation of speed and G forces and there’s a kind of a liberating feeling in that. That’s very exhilarating. It’s not just a death-defying thing. As you know, if you go on a rollercoaster 20 times, you lose the fear.

JL: When you’re racing a Formula One car David, there’s real danger. I mean, you could flip over and die. You can really crash and burn. When you’re on a rollercoaster you have all those sensations of speed and G force and falling, but you know you’re safe. The theory is people go to horror films to experience that stuff, but be safe. But you don’t think so?

DC: I don’t think that seeing a horror film is the same as going on a rollercoaster ride. A rollercoaster ride is visceral and not meditative. A good horror film should have elements of both. A rollercoaster ride is devoid of philosophy, as far as I’m concerned.

JL: Okay, I give up. But why do people want to go see films that will terrify them?

DC: Well, they don’t all. My family dentist once said to me,“Why should I go see your horror films? I have enough horror in my own life!”

Dawn of the Dead[aka Zombi, George A. Romero, 1978] Romero’s vision of the North American consumer; a fairly typical day at the mall.

ZOMBIES

For decades, zombie movies drew on the traditional figures of Haitian Voodoo ritual. The clichéd image of a zombie was a tall, lean black man with glassy eyes. A prime example appears in I Walked With A Zombie[Jacques Tourneur, 1943], which is a much better movie than it sounds. Zombies were called the “Walking Dead” and they tended to shamble along. They may have been slow, but they just kept coming…

The mystical figure of Baron Samedi, Master of the Dead, a spirit (or Loa that can be summoned by a Voodoo priest (or houngan), is always depicted wearing a top hat. Baron Samedi has been portrayed onscreen by Geoffrey Holder in the James Bond film Live and Let Die[Guy Hamilton, 1973] and by Don Pedro Colley in the blaxploitation/horror/gangster picture Sugar Hill[Paul Maslansky, 1974]. A Voodoo priestess is called a mambo (also the name of a popular Latin American dance).

In Haitian Voodoo, a houngan uses poisons and ritual burials to convince victims that they are dead. The houngan then uses their new zombies to pick sugar cane and for other menial tasks. Many claim that this practice continues today. In Voodoo and in the movies, zombies are symbols of exploitation and social decay. Hammer Films’ The Plague of the Zombies[John Gilling, 1966] places witchcraft (Voodoo)-created zombies at the center of a story of typically English class warfare, using the zombies as a menace and as slave labor.

Zombies are basically the Walking Dead. How the dead come to be walking varies. In Stuart Gordon’s wild Re-Animator[1985], a concoction of glowing green liquid injected by syringe does the trick. In An American Werewolf In London[John Landis, 1981], the unfortunate lycanthrope David Kessler (David Naughton) is first visited by his increasingly decayed dead best friend Jack (Griffin Dunne), then surrounded by the gory victims of his “carnivorous lunar activities” who demand he kill himself.Apparently, when the “last remaining werewolf” is destroyed, his victims will cease being “undead.” So are Jack and his companions zombies?

What about those poor unfortunates in all those movies who turn into flesh-eating crazies thanks to medical experimentation, atomic radiation, pollution, or some bizarre virus?

The term zombie has become a bit like pornography—even if we are unable to make a definitive description of exactly what a zombie is, we know a zombie when we see one!

The Spanish zombies in Rec[co-directed by Jaume Balagueró and Paco Plaza, 2007] or the British zombies in Shaun of the Dead[Edgar Wright, 2004], and 28 Days Later[Danny Boyle, 2002] or the French zombies in Paris by Night of the Living Dead[Grégory Morin, 2009] and La Horde[Yannick Dahan, Benjamin Rocher, 2009], the New Zealand zombies in Peter Jackson’s Dead Alive[aka Braindead, 1992], and all those Italian zombies from Michele Soavi’s Dellamorte Dellamore[aka Cemetery Man, 1994] to Lucio Fulci’s Zombi 2[1979] to the Japanese (I swear this is a real movie) Big Tits Zombie[Takao Nakano, 2010] to the all-American Zombie Strippers[Jay Lee, 2008], I think we can safely say that zombies are an international audience favorite.

My personal favorite zombie movie is King of the Zombies[Jean Yarbrough, 1941], a low-budget B movie from Monogram, in which the wonderful Mantan Moreland’s supporting character, Jefferson “Jeff” Jackson, steals the picture as the only one who actually sees the zombies. He is then hypnotized by the villain to believe that he is a zombie, too. Once he thinks he is a zombie, his fear of the authentic zombies is replaced by feelings of camaraderie and good fellowship. Of course, when he discovers that he is not a zombie, he runs in terror from his former “brothers.”

In the 1960s, movie zombies started to eat the flesh of the living, often feasting specifically on brains. In the very funny Return of the Living Dead[Dan O’Bannon, 1985] the zombies even speak! A police car is surrounded by hungry zombies who viciously attack the two cops inside and then gleefully eat their brains. The patrol car’s radio crackles and a voice asks if they need assistance. One of the zombies clumsily takes the microphone and croaks, “Send more cops.”

The Walking Dead is now no longer an all-encompassing term for zombies. In films like Return of the Living Deadand 28 Days Later[Danny Boyle, 2002], the zombies no longer shamble along, they can also run very fast. Assorted causes for their zombification have gone way beyond Voodoo to include atomic radiation, alien invasion, pollution, and weird Ebola-type viruses, sometimes natural, sometimes produced by the military. In Dead Alive, an outbreak of crazed, flesh-eating zombies in New Zealand is started by the bite of a “Sumatran Rat Monkey!”

In contemporary films, zombies are frequently agents of anarchy and represent the collapse of an orderly society. Films like 28 Days Later, Zombieland[Ruben Fleischer, 2009], and both versions of Dawn of the Dead[George A. Romero, 1978 and Zack Snyder, 2004], unleash berserk, flesh-eating zombies and suddenly, it’s every man for himself as hordes of rotting corpses roam the streets and chaos reigns.

Zombies have now evolved into modern agents of the Apocalypse. Based on a video game, the Resident Evilseries of films stars Milla Jovovich as a former employee of an evil corporation who battles zombies through four movies and counting: Resident Evil[Paul W. S. Anderson, 2002], Resident Evil: Apocalypse[Alexander Witt, 2004], Resident Evil: Extinction[Russell Mulcahy, 2007], and Resident Evil: Afterlife 3D[Paul W. S. Anderson, 2010].

Maybe one of the reasons for the increasing popularity of the zombie movie is the aging population of the Western world. As the director David Cronenbergpointed out, “As we grow older, we transform into something monstrous. Our minds begin to fail us, as do our bodies themselves.” Whether or not we like to admit it, we have all felt a horror of the aged and infirm. No one escapes the indignities and terrors of old age, physical decrepitude, and death. One day, the ravages of time will reduce all of us to shambling, drooling, “walking corpses” covered in lesions and clad in loose-fitting hospital robes. As Walt Kelly’s brilliant comic-strip character Pogo discovered, “We have met the enemy, and he is us.”