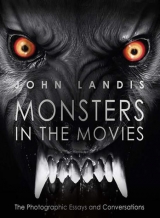

Текст книги "Monsters in the Movies "

Автор книги: Джон Лэндис

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 4 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

An American Werewolf in London [John Landis, 1981]

Scotland Yard’s Inspector Villiers (Don McKillop) attacked by the werewolf in Piccadilly Circus.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

Michael Jackson’s Thriller [John Landis, 1983]

Michael Jackson as a teenage werecat “strangling” me on the set of Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Photo by Douglas Kirkland.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

The Werewolf [Lucas Cranach the Elder, -]

This woodcut by the German Renaissance painter, engraver, and printmaker shows a lycanthrope attacking a village.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

Little Red Riding Hood [Charles Perrault, 17th century]

German postcard illustration [c. 1900]. Charles Perrault wrote the first account of the French folk tale in the 17th century. In Perrault’s telling, Little Red Riding Hood ends up as a tasty meal for the devious Wolf.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

The Wolf Man [George Waggner, 1941]

This ad for Universal Studios’ newest monster stresses the transformation “from Man to Beast” as a major marketing strategy.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

Lon Chaney, Jr. as the tragic Wolf Man of the title holding the lovely Evelyn Ankers in his arms. I’ve never understood why the werewolf that bit him (the Gypsy Bela, played by Béla Lugosi) was a proper, four-footed wolf and Talbot became a two-footed wolf man.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

Cat People [Jacques Tourneur, 1942]

French actress Simone Simon stars as Irena Dubrovna in this intelligent thriller from the Val Lewton B Picture Unit at RKO Studios. The sequence where a jealous Irena follows her husband’s secretary to her apartment building’s swimming pool is still eerie after all these years.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

Werewolf of London [Stuart Walker, 1935]

Henry Hull refused to wear the make-up Jack Pierce designed for the werewolf, as he felt it hid too much of his face. Pierce and Hull settled on the face pictured here in a highly retouched publicity photo from the original release. Pierce ended up using his first Werewolf of Londondesign on Lon Chaney, Jr. in The Wolf Man.

“The werewolf is neither man nor wolf, but a Satanic creature with the worst qualities of both.”

Dr. Yogami (Warner Oland), Werewolf of London

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

The Curse of the Werewolf [Terence Fisher, 1961]

Oliver Reed makes a splendid werewolf in this handsome Hammer film. Roy Ashton, Hammer’s go-to monster maker, did Reed’s werewolf make-up.

“Their dream of love a nightmare of horror!”

From the trailer for The Curse of the Werewolf

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

Dog Soldiers [Neil Marshall, 2002]

A squad of British soldiers on a training mission in the Scottish Highlands has a nasty encounter with a family of werewolves in Neil Marshall’s exciting, action-packed horror movie.

“They were always here. I just unlocked the door.”

Megan (Emma Cleasby), Dog Soldiers

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

How to Make a Monster [Herbert L. Strock, 1958]

Actor Gary Clarke in Michael Landon’s Teenage Werewolf make-up from the earlier film, poses with Gary Conway, the Teenage Monster from I Was a Teenage Frankenstein[Herbert L. Strock, 1957].

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

Ginger Snaps [John Fawcett, 2000]

A smart take on werewolf mythology and a clever examination of teenage angst and sexuality. Two “goth” sisters, Ginger and Brigitte Fitzgerald (Katharine Isabelle and Emily Perkins) meet the Beast of Bailey Woods and find out that it’s a lycanthrope.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

The Howling [Joe Dante, 1981]

Serial murderer Eddie Quist (Robert Picardo) is the epitome of the young punk our parents warned us to stay away from. He is also a werewolf. Note the poster design for The Howlingis essentially the other side of the poster for I Was a Teenage Werewolf!

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

The Twilight Saga: New Moon [Chris Weitz, 2009]

The second film in the Twilightseries. In this picture all of the werewolves have nice bodies and rarely wear shirts in their human form.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

Wolf [Mike Nichols, 1994]

Jack Nicholson with Michelle Pfeiffer in a modern werewolf story. James Spader steals the picture as a rival werewolf.

AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON

This was my attempt to make a movie dealing with the supernatural in a completely realistic way. Because there is no such thing as men who become monstrous wolves when there is a full moon, I tried to explore how one would react when confronted with this as truth. What do you do when the unreal is real? That was my premise and An American Werewolf in Londonis the result.

David Kessler (David Naughton) wakes up to find himself naked inside the wolf cage in The Regent’s Park Zoo.

David Kessler (David Naughton) halfway through his painful metamorphosis.

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

A publicity shot of David surrounded by the victims of his “carnivorous lunar activities” at a porno theater in Piccadilly Circus. His best friend Jack (Griffin Dunne), now also one of the “Living Dead,” is on his right. Jack is not a fresh kill and by now looks a little worse for wear.

“The wolf’s bloodline must be severed. The last remaining werewolf must be destroyed. It’s you, David!”

Jack (Griffin Dunne), An American Werewolf in London

The transformation from a man into four-legged “hound from hell” is a painful one. Sinew, muscle, and bone stretch, bend, and crack. New, non-human flesh grows and limbs elongate, teeth become fangs, hair sprouts from all over the body, claws burst from fingers. The jaw unhinges from the skull and actually begins to grow into a snout. I recommend you do not try this at home.

IN CONVERSATION

Joe Dante

“It’s confronting death without having to really die.”

Director Joe Dante checks a shot on the set of Gremlins[1984].

Werewolves[ Book Contents]

JL: So, Joe, here on your office wall you have a poster from Creature From the Black Lagoon[Jack Arnold, 1954]…

JD: One of the great monsters of all time.

JL: Why?

JD: It’s one of the best-designed monsters. It’s a triumph, considering what was available at the time. There has to be something recognizably human about a great monster. And the greatest thing about the Creature is, of course, that he lusts after Julie Adams!

JL: But what’s he going to do when he gets Julie Adams? Isn’t he a fish?

JD: Well, I think he’s certainly part fish.

JL: Okay, we love the Creature. And you also have a large poster of La Belle et la Bête[Jean Cocteau, 1946] on the wall.

JD: Yes. That monster is also a great design, by Jean Cocteau. It’s kind of a Wolf Man design. The great thing about wolf men characters is that they are sort of dog-like, and so we tend to feel a kinship to them. The Jack Pierce make-up for The Wolf Man[George Waggner, 1941] is great, but there is something dog-pet-like about him.

JL: What about your werewolves in The Howling[1981]?

JD: The werewolves in The Howlingwere an attempt to get away from that dog-like look. We thought they should be more lupine, like they are in the old woodcuts.

JL: Do you really think the most effective monsters are humanoid?

JD: Well, what is a monster? A monster is something that isn’t normal, that doesn’t look like regular people. In the Middle Ages, anybody who had any kind of a deformity was considered to be a monster. There are a lot of superstitions about deformity. There are many fantasy creatures that are half man and half something else, like the Minotaur. But the fascination for monsters for my generation was basically that we were powerless kids and monsters were misshapen individuals who didn’t fit into society, who didn’t have any power, and who had to strike back. So, as a kid, you felt a kind of power watching a monster doing his stuff.

JL: Do you have a theory on why people like monster movies?

JD: It’s a difficult question. It’s confronting death without having to really die.

JL: What was the first monster movie that genuinely frightened you?

JD: I remember finding Christopher Lee’s Frankenstein Monster very scary [ The Curse of Frankenstein, Terence Fisher, 1957].

JL: How old were you? Five?

JD: I was eleven. I imagined that he was going to be coming upstairs from the cellar in our house! The whole thing about these movies is that you took them home with you. When I saw Them![Gordon Douglas, 1954], the giant ants made a sort of cricket-like, chirping kind of noise, very much like the sounds that would come from the field behind my house. Whenever a tree branch would rap on the window pane, I would think it was a giant ant antenna!

JL: But you really enjoyed seeing these movies, even though they would haunt you when you got home.

JD: I would come home and have nightmares, and my parents would say, “If you’re going to have nightmares, then why do you go to see these pictures?”

JL: And how would you answer them?

JD: “I have to.” I had to go see them. I couldn’t not go. I loved those movies. I loved all movies when I was a kid—particularly cartoons—but there was something about those pictures. They weren’t like other movies. They took place in worlds that I couldn’t even imagine, places that I couldn’t go to.

JL: The Exorcist, for me, is still probably the most successful horror movie.

JD: Yeah, it’s a brilliantly nasty movie. It’s very cleverly put together. At the beginning of the movie there are no make-up tricks or revolving heads or green vomit. By the time you get to that stuff, the audience has been pummelled into a state of being unable to resist watching whatever they’re going to do. They’ve got a girl peeing on the floor, they’ve got her masturbating with a crucifix… The movie breaks down your defenses until you’re just numb and ready to take all of the classic horror tropes which, had they been at the beginning, would not have worked.

JL: What was the first monster movie you saw?

JD: The Mad Monster[Sam Newfield, 1942]. It’s about a mad scientist (George Zucco) who turns this dim-witted handyman (Glenn Strange) into a werewolf. The reason this picture was so fascinating to me was that there was a little girl in it, whom the monster kills off-screen. We just see her ball bouncing back into frame.

JL: Were you scared by it?

JD: Sure I was scared: He killed a little girl! But it was a contained scared, because I saw it on TV. When I saw movies in the theater, that’s when I had nightmares. When you’re in a big theater and it’s dark, it’s truly scary! I was small and I didn’t want to have any heads to see over, so I would always sit in the front row, looking upwards, which I’m sure is why I have to wear glasses. I really liked movies that were about things that didn’t happen in real life—the fantastic. And in the early ’50s, when the space movies came out– This Island Earth[Joseph M. Newman, 1955] was a revelation—I was in heaven.

JL: The visual effects and those vivid Technicolor colors still hold up.

JD: Plus it was written on the level of a ten year-old. It’s fabulous! I saw Invaders From Mars[William Cameron Menzies, 1953] and then Forbidden Planet[Fred M. Wilcox, 1956] when they came out. If you saved up enough Quaker Oats box–tops you could get into that for free…

JL: You’re only five years older than I am and it makes such a difference to the films you actually saw in a movie theater.

JD: It makes a tremendous difference, because from ’53 to ’58 were a kind of golden years for science fiction movies.

JL: I saw The 7th Voyage of Sinbad[Nathan H. Juran] at the Crest Theater on Westwood Boulevard in 1958. But those other films I saw on television in black and white.

JD: Well, that was the beginning for you, but I had already been watching sci-fi and horror films for a long time at the movies. They were marketed to kids. You’d maybe have one friend, or two, who liked monster movies, but you really didn’t know many people who liked them, so you felt a little isolated. But when you went to the supermarket and you saw Famous Monsters of Filmlandmagazine on the shelf next to Lady’s Home Journal, you realized: “My God, there must be other people like me out there!” I spent years writing letters to Famous Monsters, trying to get my name in it. If you could get your name in it, you were immortal! I wrote letters about everything: all the movies I’d seen, who were my favorite monsters, whatever.

I finally got to the point where I wrote about the worstmovies I’d ever seen. It was published in the magazine as an article titled “Dante’s Inferno!” And when Forrest J Ackerman sent me the magazine, annotated with “Go, Joe! Go!” it was the greatest thing that had ever happened to me. I was 12 or 13. Then I read the article and, of course, he’d completely re-written it. He used words like “symbiotic”—things I didn’t even understand. But nonetheless, I felt like, “Wow! I’m part of a community.” There was this feeling of solidarity with other kids like me. Now there are online fan communities, but there wasn’t anything like that then. If you wanted to find out about a movie, you had only the TV guide. If you went to the library, the movie books were very scholarly and serious and not interesting to kids. The great boon of Famous Monsterswas that it got people interested in film history.

JL: Yeah, it had articles not just about actors, but on writers, directors, technicians… like Willis O’Brien, Ray Harryhausen, Jack Pierce, Fritz Lang, Tod Browning, Lon Chaney, Richard Matheson, James Whale, and on and on.

JD: Famous Monsters of Filmlandput all those disparate strands together in a way comprehensible to kids.

JL: Most horror magazines and websites now are just about maiming and killing. People are really into gore!

JD: It’s all spectacle. It’s pure, transgressive spectacle. It involves the same kinds of emotions that the Romans experienced when the Christians were thrown to the lions. Except in movies, it’s safe, we’re not really killing anybody. Now extreme gore is an accepted part of the way films are made. If you have a gory death scene, you can build a whole film around it, like The Final Destination[David R. Ellis, 2009].

People are so jaded. They’ve seen every plot, they’ve seen every twist, they’ve seen every gore effect. They’ve seen it all! And there are many things competing for their attention now that didn’t exist when we were growing up. Plus, they know nothing about film; they know nothing about film history. They don’t know who Jimmy Stewart was! They don’t know!

JL: It kind of freaks me out.

JD: And you say, “How ignorant of them,” but the fact is, in order to know about something you have to see it! The Marx Brothers—who are they? Laurel and Hardy? Nobody programs them. People don’t want to see them.

JL: My kids grew up with all the old movies, so I was so shocked when my daughter brought a bunch of girls home for a sleepover and she wanted to put The Women[George Cukor, 1939] on for them. The girls refused to watch it because it was in black and white! It was very upsetting to me.

JD: The Marx Brothers, Harold Lloyd, Buster Keaton, and all that kind of stuff is only going to be kept alive in universities. They are no longer part of popular culture. This stuff runs only on cable or satellite. It’s considered niche programming.

JL: Why do you think that so many vampire, werewolf, and zombie movies are now being made?

JD: It’s an astonishment to me—particularly because I was loyal to the genre when people thought it was trash, and now it has become mainstream. The fact is that the motion picture industry has become a glorified B-movie factory. Nowadays, the studios mine all the old, low-budget serials and monster titles, give them massive budgets, and cast them with big stars.

JL: Well, that’s directly because of Spielberg and Lucas!

JD: Exactly! But there was a moment during the Jawsand Star Warsperiod in the ’70s, when it seemed like movies were going to grow up. Look at what the studios made in those decades. But now it’s like the suits realized: “Wait a minute! We can just make fantasy films with no content and they will all show up all over the world! So now it’s all elves and Lord of the Rings, special effects in Transformers… it’s non-content film. Films that aren’t aboutanything.

JL: Gremlins[Joe Dante, 1984] was a case where there was a new fantasy film with a political subtext. And the wonderful malevolence of the Gremlins was so subversive! And Gremlins 2: The New Batch[Joe Dante, 1990] had some brilliant stuff in it. I saw that movie a hundred times—because my son Max adored it. But there are extraordinary moments in that. Really funny, brilliant, and dark…

Okay, enough about you. Let’s talk about some specific monsters: The Mummy.

JD: The bromide about the Mummy was that you just need to walk away, and if you walked fast, you could get away from him. But when I was a kid, even though he was slow, he always got his victims. So it seemed to me that he had this magical power.

JL: And vampires?

JD: They’re back. And now they’re sexy and young, and they’re…

JL: Mormon!

JD: Absolutely, the whole appeal of the Twilightthing is that they can’t have sex. It’s the abstinence thing—that’s why parents are saying: “You should see these Twilightmovies; they’re really good!”

JL: So summing up, do you have any thoughts about why it is we like monsters?

JD: They’re sources of melodrama; they’re dangerous; they make people run in fear; they decimate; they kill; they do all the things that a bomb does. Maybe it’s an embracing of death that starts at an early age. But basically, monsters do bad things and usually cause lots of death and heartache. Monsters are metaphors. Godzilla is a perfect example. Here is atomic war come to life, to be visited upon the people of Japan. That would be a good game: Name the monster movie and then the metaphor!

Colin Clive as Henry Frankenstein and Dwight Frye as his assistant Fritz in Frankenstein[James Whale, 1931].

MAD SCIENTISTS

Scientific curiosity is the bedrock of progress. Sometimes, however, scientific research can be harmful to those conducting it; Madame Curie almost certainly died from the effects of the very radioactivity she discovered.

In Die, Monster, Die![Daniel Haller, 1965], Boris Karloff’s work with a radioactive meteor in the cellar of his house has catastrophic consequences for his entire family. In The Invisible Man[James Whale, 1933], Dr. Jack Griffin (Claude Rains) is driven mad by the injections of “Monocane,” a drug he has discovered that makes him invisible. And woe to poor Dr. Jekyll, whose research into what we now call psychopharmacology releases his inner, murderous personality, his alter ego Mr. Hyde. Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) learns too late the power of the technology of the lost race of Krell in Forbidden Planet[Fred M. Wilcox, 1956] when it unleashes his subconscious thoughts as a living creature of pure energy. The terrifying Monster from the Id is only seen in outline when it is being blasted by lasers. This memorable and fearsome monster was animated by Joshua Meador, on loan to MGM from the Walt Disney Studios.

The insane Dr. Moreau from H. G. Wells’ novel The Island of Dr. Moreauis a ruthless scientist performing radical surgeries on animals to create men. Wells’ short novel was written in 1896 as an anti-vivisectionist tract and the three feature films based on the book have all emphasized the extreme sadism of Dr. Moreau. Dr. Moreau (Charles Laughton) in Island of Lost Souls[Erle C. Kenton, 1932], rules the “manimals” he’s made by their fear of “The House of Pain”– the operating room where he struggles to cut out “the stubborn beast flesh.” The Beast Man Sayer of the Law (Béla Lugosi) confronts the bullwhip-wielding Dr. Moreau with his plaintive, “We are not men. We are not beasts. We are things.” The Beast Men finally revolt, turning Moreau’s gleaming scalpels on their tormentor. Laughton’s screams as he is dragged off to The House of Pain live long in the memory. This truly disturbing movie could be used as an “anti-genetic engineering” brochure in the present day!

The most famous mad scientist would have to be Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) in the classic 1931 Universal Picture, Frankenstein[James Whale]. His experiments to revive with electricity the creature he has pieced together from dead bodies created the definitive movie monster. As portrayed by Boris Karloff, in make-up by the great Jack Pierce, the Monster is both to be feared and pitied. Karloff’s brilliant performance powerfully conveys the Monster’s pain, innocence, and brutality. The tremendous popular success of Frankensteingave James Whale the freedom to create its extraordinary sequel, The Bride of Frankenstein[1935], which gave us not only Elsa Lanchester’s unforgettable performance in the dual role of author Mary Shelley and the Bride of the Monster, but the maddest of all mad doctors, Doctor Septimus Pretorius (Ernest Thesiger).

Mad doctors tend to have bizarre obsessions; my personal favorite is the brain transplant. Dracula himself (Béla Lugosi) plans to put Lou Costello’s brain into the skull of the Frankenstein Monster (Glenn Strange) in Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein[Charles Barton, 1948]. George Zucco transplants the brain of a young man into a gorilla in The Monster and the Girl[Stuart Heisler, 1941] and Dr. Sigmund Walters (John Carradine) puts the brain and glands of a young woman into the skull of an ape, creating the attractive, yet mysterious Paula Dupree (Acquanetta) in Captive Wild Woman[Edward Dmytryk, 1943].

A “matter transportation device” has tragic results when a common fly is inadvertently dematerialized along with the scientist Andre Delambre (Al Hedison) conducting the experiment. When Andre rematerializes, he has a giant fly’s head and one large claw in The Fly[Kurt Neumann, 1958]. Meanwhile, the little fly now has one tiny arm and a tiny human head! The scene of this little fly trapped in a spider web as a huge and hideous spider bears down on him (his tiny human face squeaking “Help me!”) is one of the silliest, yet most upsetting, images in all of the horror films of the 1950s.

In David Cronenberg’s excellent remake of The Fly[1986], scientist Seth Brundle (a wonderful performance from Jeff Goldblum) is doomed to repeat the experiment, with more profound but equally shocking and tragic results.

The experiments of Dr. James Xavier (Ray Milland) with X-ray vision also go badly awry. His vision grows more and more powerful until he goes mad and tears out his own eyes in X[aka The Man with the X-Ray Eyes, Roger Corman, 1963].

In Altered States[Ken Russell, 1980], Dr. Edward Jessup (William Hurt) and his colleagues experiment with sensory deprivation water tanks and drugs to achieve “biological devolution.” Jessup emerges from his tank once as a primitive man and once again as “conscious primordial matter.”

In Swamp Thing[Wes Craven, 1982], Dr. Alec Holland works in the swamps with his sister doing bio-medical research. He is trying to create a plant/human hybrid that can live in extreme environments. It should come as no surprise that Dr. Holland ends up a hybrid plant person himself.

Dr. Stoner (Strother Martin) wants to turn his handsome assistant into a large snake in SSSSSSS[aka SSSSnake,Bernard L. Kowalski, 1973]. In both The Incredible 2-Headed Transplant[Anthony M. Lanza, 1971] and The Thing with Two Heads[Lee Frost, 1972], neither the recipient nor the donor of the extra head is very happy with the results! After his wife is decapitated in a car accident, Dr. Bill Cortner (Jason Evers) keeps her severed head alive in his basement lab in the country while he scouts strip joints for the right body to sew it onto! His wife (Virginia Leith), or rather her head, is now The Brain That Wouldn’t Die[Joseph Green, 1962]. She develops telepathic communication with a hideous monster locked in the basement closet—the result of her husband’s earlier failed experiments. Without giving too much away, just let me say that this film has one of the strangest endings in movie history.

The fundamentally conservative nature of the horror film tends to reinforce the reactionary idea that, “There are some things Man is not meant to know.” Intellectual curiosity is punished and those who dare question conventional wisdom suffer the consequences. I think this would be a good place to point out that Galileo was right, and the Church wrong!