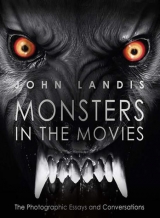

Текст книги "Monsters in the Movies "

Автор книги: Джон Лэндис

Жанр:

Ужасы

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 3 (всего у книги 15 страниц)

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Dracula Has Risen From The Grave [Freddie Francis, 1968]

The priest has lost his faith and the man his nerve when they stake Count Dracula.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

But their aim is not true and Dracula pulls out the stake (with lots of gushing red gore, unusual at the time)!

Vampires[ Book Contents]

The Vampire Lovers [Roy Ward Baker, 1970]

Ingrid Pitt as Marcilla Karnstein, a character based on the J. Sheridan Le Fanu novella Carmilla. One of the so-called Karnstein Trilogy of lesbian-themed vampire films from Hammer.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

General von Spielsdorf (Peter Cushing), having driven a stake through Marcilla’s heart, cuts off her head, just to make sure she’s really dead this time.

“You must die! Everybody must die!”

Marcilla Karnstein (Ingrid Pitt), The Vampire Lovers

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Twins of Evil [John Hough, 1971]

Mary and Madeleine Collinson, identical-twin Playboy Playmates, are the stars of this, the third in the Karnstein trilogy from Hammer. Peter Cushing shines as a fanatical Puritan eager to burn witches and stake vampires.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Near Dark [Kathryn Bigelow, 1987]

A rushed happy ending is the only flaw in Bigelow’s Western vampire masterpiece. Lance Henriksen and Bill Paxton (pictured) give fantastic performances as outlaw vampires trying to survive in the contemporary American West. Joshua John Miller as Homer, an aged vampire trapped forever in a child’s body, is both repulsive and heartbreaking. A very good movie.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Bram Stoker’s Dracula [Francis Ford Coppola, 1992]

Sadie Frost as Lucy is not too pleased to see that cross, in Coppola’s imaginative retelling of Dracula.

“Lucy is not a random victim… She is the Devil’s concubine!”

Van Helsing (Anthony Hopkins), Bram Stoker’s Dracula

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Innocent Blood [John Landis, 1992]

Anne Parillaud as the beautiful and lonely vampire Marie, who will only take “innocent blood” to survive. She accidentally lets violent mob boss Sal “The Shark” Macelli survive her attack, creating an even more monstrous mobster who envisions creating an army of mafia vampires. Marie joins forces with undercover cop Joe Gennaro (Anthony LaPaglia) to destroy Macelli. Robert Loggia is brilliant in a brave and very funny performance. With Don Rickles as Manny Bergman, Macelli’s lawyer. From an original screenplay by Michael Wolk.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Interview With the Vampire [Neil Jordan, 1994]

Brad Pitt, Kirsten Dunst, and Tom Cruise are all vampires in this big-budget movie version of the Anne Rice novel.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Van Helsing [Stephen Sommers, 2004]

Josie Maran as the flying vampire Marishka.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Richard Roxburgh as Count Vladislaus Dracula, holding Kate Beckinsale as Anna Valerious, looking into a mirror. Mel Brooks repeated this gag in Dracula: Dead and Loving It[1995].

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Roxburgh tries to remain as menacing as he can under the circumstances.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

30 Days of Night [David Slade, 2007]

Danny Huston as Marlow, the leader of the vampires who besiege a small Alaskan town in the dead of winter. Huston is terrific as a vicious vampire out for blood.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Let the Right One In [Tomas Alfredson, 2008]

Lina Leandersson as Eli in this marvelous Swedish vampire film based on the novel and screenplay by John Ajvide Lindqvist. A young boy named Oskar (Kåre Hedebrant) is bullied by the other boys in his small town. He slowly builds a friendship with the strange girl who moves into his apartment block with her uncle. A quietly great horror film.

“I live off blood… I’m twelve. But I’ve been twelve for a long time.”

Eli (Lina Leandersson), Let the Right One In

Vampires[ Book Contents]

Daybreakers [Michael Spierig, Peter Spierig, 2009]

A variation on Richard Matheson’s novel I Am Legend(which has been made into three films already). A pandemic has turned most of the world’s people into vampires and they want a cure. Good actors and cool special effects.

IN CONVERSATION

Christopher Lee

“I never looked upon my films as horror films.”

Schlock reads Famous Monsters of Filmlandmagazine sitting next to its editor, Forrest J Ackerman. On the cover is Sir Christopher Lee as Dracula.

Vampires[ Book Contents]

JL: Chris, you were just about to say why you shy away from the term “horror film.”

CL: It’s a very simple answer. I did films with Boris Karloff who, like myself, made his name as a monster. He was a wonderful man, a superb actor, far better than the parts he was often given to play. What he had to do, and what I had to do, was to make the unbelievable believable. And that’s very difficult, especially with today’s audience. The reason I don’t like the word “horror,” is because it conjures up something really nasty, horrific, horrendous, evil, vile. The word that Boris used to use, and indeed I use, is “fantasy.” The French always refer to these films as “films of the fantastic,” which I think is a very good description. I never looked upon my films as horror films. I always tried to give the impression that the characters I played were doing things they couldn’t help doing. And Boris did the same.

JL: You’ve played some of the classic monsters. You are the definitive Dracula, and you’ve played the Mummy, as well as Frankenstein’s Monster. Your Dracula is pretty ferocious, whereas your Frankenstein’s creature is very sympathetic…

CL: This is what I’ve always tried to do. Even when playing, not necessarily a monster, but the bad guy, I’ve always tried to do something, say something, the audience doesn’t expect.

JL: Your performance in The Curse of Frankenstein[Terence Fisher, 1957] is fabulous.

CL: The Creature is a very pitiful character. He didn’t ask to be made; he’s a victim. More so than the people he kills.

JL: I think the people he kills are victims, too.

CL: Well, I didn’t kill many people, as I remember. And Boris didn’t either. In (the Karloff Frankenstein), there was that famous scene when he throws the little girl into the lake thinking that she will float like the flowers. The censors cut that out, but I believe it’s back in now. That scene is pitiful, pitiful. The audience has to see this other side to the Creature.

JL: What’s interesting about The Curse of Frankenstein, is that Peter Cushing’s role, Dr. Frankenstein, is the real monster.

CL: Oh, absolutely. As you say, I’m the victim.

JL: And in the sequels, Frankenstein’s creature becomes less and less important.

CL: I never saw them.

JL: Well, they vary greatly in quality. But Peter’s always good!

CL: He was a superb actor.

JL: Marty Scorsese said that your entrance in Horror of Dracula[aka Dracula,Terence Fisher, 1958] made a huge impression on him. You walk quietly down the stairs and say, “I am Count Dracula. And this is my house.” Something elegant and simple like that.

CL: I remember our first night in New York with Peter [Cushing]. I’d never been to America. This was about ’57, I think. There was a great big building near the theater that was covered with an enormous painting of me (as Dracula) carrying one of the girls.

JL: How many stories high was it?

CL: At least 10 stories. That made me reel! Then we had to go to the first performance. And I’m not good in public, few actors are. I said to Peter, “I don’t think this is a very good idea.” And he said, “Oh, my dear fellow, this is what we’ve come for! We’ve got to do it!” It was close to midnight, and many in the audience had had a few, to put it mildly. So I said to Peter, “I’m going to sit in the very top row, underneath the projection booth with you, near the exit, so that if anything happens I can leave.” Because I didn’t like seeing myself on screen, and I didn’t know what the audience reaction was going to be. Finally, the lights go down, the curtains part, up come the credits, and I recall there was a coffin with my name and blood splashes onto it. There was a huge roar of applause, and then the moment comes where you see me at the top of the stairs: a silhouette. The place exploded. Everyone shouting and yelling, and laughing, and I thought, “Oh God, this really is the end.” And I walk down the stairs in a perfectly normal way, and I say quite calmly, “Mr. Harker,” or “Good evening, Mr. Harker” or something, and he says, “Count Dracula,” and I say, “Yes, I am Dracula,” or something… The audience went completely quiet! Total silence for the rest of the film!

JL: The audience must have reacted to the scares?

CL: A few shudders or squeaks, but every time I appeared on screen—silence. The biggest shock in the film, was when the girl [Valerie Gaunt credited as “Vampire Woman”] tries to seduce Jonathan Harker. And there’s a shot of me in the doorway, teeth bared, wearing those contact lenses—couldn’t see a thing– and I leap up onto a table, and I leap off—that’s no stunt, no fake—shoot across the floor, fling her aside and go straight for him. There were no cuts. I don’t think anybody had ever seen an actor playing a vampire do anything like that before.

JL: Your Dracula is terribly physical, and very, very sexual.

CL: Which I did not intend.

JL: Whether you intended it or not, it made a big impression.

CL: I know it did, but I tried to play him as a man with a kind of compulsion. I obviously gave the impression that he enjoyed it.

JL: You played it very sexual, though, Chris. You’re saying it was an accident?

CL: I tried to make him attractive to women. That was in the script!

JL: Now, what about all the sequels. They got sillier and sillier.

CL: That gives rise to a true story. The first film came out, and it rocketed around the world.

JL: It was a huge hit.

CL: And it made me world famous. As Dracula, though, not necessarily as Christopher Lee.

JL: But not only was your Dracula so striking and remarkable, it was really the first color Dracula movie. And the blood was so Technicolor red.

CL: Well, that was Hammer’s idea. Eight years later, they asked me…

JL: …It was 8 years until the second one? I didn’t know that.

CL: Yes, 7 or 8. I did Rasputin[full title, Rasputin, the Mad Monk, Don Sharp, 1966] and Dracula: Prince of Darkness[Terence Fisher, 1966] back to back. Same sets. When I read the script, I said to my agent, “I’m not saying any of this dialog. It’s appalling.”

JL: You don’t say anything in the movie!

CL: Not a word.

JL: But you have a hell of a presence!

CL: When Chekhov went to see one of his plays at a local theater, they asked him at the end what he thought of it, and he came up with this wonderful expression: “Not enough gunpowder.” That’s the secret. If you have the physical presence, all right: you’re lucky. If you have power, well, you’re lucky. But, gunpowder, that’s the real secret!

JL: Well, your Dracula certainly has fire and brimstone.

CL: I refused to do the second one at first. In the end, I played Dracula five or six times…

JL: I hope they paid you well!

CL: Oh, you’re joking. I think they paid me about £750.

JL: Even for the later ones?

CL: I think they paid me a little bit more later, but not much. Certainly not five figures.

JL: But you were the selling point of the movies!

CL: I bought my first car when I was 35. It was a second-hand Merc. I could just about afford it. Anyway, the process went like this: The telephone would ring and my agent would say, “Jimmy Carreras [President of Hammer Films] has been on the phone, they’ve got another Dracula for you.” And I would say, “Forget it! I don’t want to do another one.”

JL: So how would Hammer get you to agree?

CL: I’d get a call from Jimmy Carreras, in a state of hysteria. “What’s all this about?!” “Jim, I don’t want to do it.” “You’ve got to do it!” “Jim, I don’t want to do it, and I don’t have to do it.” “No, you have to do it!” And I said, “Why?” He replied, “Because I’ve already sold it to the American distributor with you playing the part. Think of all the people you know so well, that you will put out of work!” Emotional blackmail. That’s the only reason I did them.

JL: “Emotional blackmail” is a tradition in the movie business. Tell me about The Mummy[Terence Fisher, 1959].

CL: The Mummy was a real person at one time, a high priest, and he falls in love with a princess.

JL: It’s a romantic story.

CL: Oh yes! This love is forbidden, and they find out, cut out his tongue, and ball him up.

JL: Was that terribly uncomfortable?

CL: Yes! Swathed in bandages. Boris [Karloff, star of the original The Mummy, Karl Freund, 1932] said it was absolute hell, because he was covered in make-up and wrapped so tightly in bandages. If he took a deep breath, the bandages would crack and you would see there was a real person underneath.

JL: Luckily for him, Karloff is only the bandage-wrapped Mummy in one scene…

CL: The way I played it, I tried to make people feel sorry for me. The problem with the role was a physical one. I had to move like an automaton, but the Mummy also had a mind of its own. Because of the bandages I could only act with my body movements and my eyes. In one of the most effective scenes, I come crashing through the windows and Peter Cushing thrusts a spear into me, which goes right through, and shoots me. And then Yvonne Furneaux comes in. And Peter shouts, “Let down your hair! Let down your hair!” while I’m strangling her with one hand. And she does. And it’s Ananka, the princess I fell in love with. I see her and I am riveted. And after quite a long time, I just turn around and walk away. Which I thought was very moving.

JL: And didn’t you have to go into a swamp?

CL: Ah, the business in the swamp: I had to carry about three or four girls, sometimes as much as 80 yards, and they were pretending to be unconscious, so they were dead weight. It didn’t help my shoulder muscles! In the swamp, Yvonne was saying to me under her breath, “Don’t drop me, don’t drop me,” and I was using the most appalling language, because I was crashing into these pipes which were producing the bubbles in the water and the mud.

JL: Which brings us to Mr. Hyde.

CL: I’d forgotten that one. I think that was one of the best things I’ve ever done. But it had a ridiculous title: I, Monster[Stephen Weeks, 1971]. And they changed Jekyll’s name.

JL: He’s not called Dr. Jekyll?

CL: Jekyll and Hyde became Marlowe and Blake. But all the other people in the story have the correct names.

JL: Why on earth would they do that?

CL: Don’t ask me!

JL: Fredric March played Hyde as a bestial, ape-like character.

CL: Yes, and Spencer Tracy was very frightening, too.

JL: Tracy played him more like a psychopath. It was John Barrymore who first made Hyde into a physical monster.

CL: Oh yes, that was extraordinary.

JL: And he did it live on stage on Broadway!

CL: I don’t know how he did that.

JL: George Folsey, the camera operator on the silent Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde[John S. Robertson, 1920], told me that on stage Barrymore would drink from the flask, then stagger and fall down behind a desk and quickly get right up again transformed into the hideous Mr. Hyde! It happened very fast. All he did was put on a pointed, bald cap and shove crooked teeth into his mouth. He could distort his face so grotesquely.

CL: I played Hyde in stages of degeneration. I became worse and worse and worse. In the name of science. Curiosity. What would happen if I took this drug? All scientists are curious. The make-up man, Harry Frampton, did a wonderful job. There were about five or six stages of degeneration.

JL: Is there any particular monster that you were frightened of as a kid?

CL: Well, I remember after seeing Boris Karloff in Frankenstein, aged 11, I used to wake up in the middle of the night and think he was in the room. And I wasn’t the only one!

The Wolfman[Joe Johnston, 2010] An atmospheric shot from the very disappointing remake.

WEREWOLVES

The belief in shape-shifting is universal. In every culture, from the ancient Greeks to the Native Americans, men and women often become animals and vice versa. In stories like the god Zeus turning himself into a swan to seduce the mortal Leda, or the magical Puck giving Bottom the head of an ass in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the theme of man-into-animal appears countless times in art and literature. In cinema, by far the most popular shape-shifter is the werewolf.

The shape-shifting “rules” change from film to film. Usually a man becomes a werewolf by being bitten by another werewolf, as in Werewolf of London[Stuart Walker, 1935], The Wolf Man[George Waggner, 1941 and Joe Johnston, 2010], and An American Werewolf in London[John Landis, 1981].

In The Curse of the Werewolf[Terence Fisher, 1961] Oliver Reed is born a werewolf because his mother was raped and he is born on Christmas Day! This movie claims that for an unwanted child to share his birthday with Jesus Christ is “an insult to heaven.” When the poor bastard baby is to be baptized, the Holy Water in the baptismal font begins to boil. Not a good sign.

In the Underworldseries of films, an entire race of werewolves battles a race of vampires for supremacy, and in Neil Marshall’s Dog Soldiers[2002], a troop of British soldiers has the misfortune of running into a family of werewolves in the Scottish Highlands. In How to Make a Monster[Herbert L. Strock, 1958], an insane make-up artist uses Michael Landon’s actual make-up and mask from the earlier film I Was a Teenage Werewolf[Gene Fowler, Jr., 1957] to turn an innocent actor into a homicidal wolf man! Val Lewton’s production Cat People[Jacques Tourneur, 1942], centers on a beautiful woman (Simone Simon) descended from an ancient European race. When her passions (jealousy and lust) are aroused, she turns into a murderous black panther!

The full moon has long been associated with violence and madness—the word “lunatic” shows the power we give the full moon. Against his will, the body of the lycanthrope changes into that of a werewolf whenever a full moon appears in the night sky.

A common term for the natural menstruation cycle of women is “the curse.” This idea is explored in the clever Canadian picture Ginger Snaps[John Fawcett, 2000]. This film, like I Was a Teenage Werewolfand The Beast Within[Philippe Mora, 1982], uses lycanthropy as a metaphor for adolescence. In adolescence, youngsters begin to grow hair in unexpected places and parts of their anatomy swell and grow. Everyone experiences these physical transformations in their bodies and new, unfamiliar, sexual thoughts in their minds. No wonder we readily accept the concept of a literal metamorphosis.

In Curt Siodmak’s original screenplay for Universal’s seminal The Wolf Man, he emphasized the notion of the werewolf as a victim. The Wolf Man of the title, Larry Talbot, (played by Lon Chaney, Jr. in all five Universal Wolf Manmovies), is horrified by his plight and spends most of his time trying to find a cure or contemplating suicide.

Every single werewolf film always has a major “transformation” sequence: Larry Talbot’s transformation was accomplished by a series of optical dissolves. Chaney sat very still (usually with his head, hands, and feet held in place) while make-up man Jack Pierce gradually applied more and more yak hair and putty to his face. This was a tedious, time-consuming process, and the use of optical dissolves resulted in a rather gentle transformation from man into wolf man.

When I wrote the script for An American Werewolf in London(written in 1969, produced in 1981), I envisioned the metamorphosis from man to beast as a violent and painful one. The character of David Kessler (David Naughton) would transform from a two-legged human into a four-legged “hound from hell.” I also specified that the sequence take place without cutaways and in bright light. The gifted make-up artist Rick Baker accomplished this with an elaborate combination of make-up, foam appliances, and what he called “change-o” body parts. These were elaborate puppet reproductions of parts of Naughton’s body (including his torso, hands, feet, head, and face) that could actually stretch and transform into the wolf monster in real time on camera. This sequence took five days to shoot. I ended up using one cutaway: of a toy Mickey Mouse silently watching. Rick won the first of his many Academy Awards for his groundbreaking work.

In Joe Dante’s terrific The Howling[1981], the character of Eddie Quist (Robert Picardo) positively relishes his lycanthropy and gleefully transforms in front of a terrified Terry Fisher (Belinda Belaski). In this movie, werewolves seem to transform either at will or from sexual arousal. TV anchorwoman Karen White (Dee Wallace-Stone) has a particularly disturbing encounter with Quist in a porno booth at a sex shop while a film of a rape is being projected. Karen White eventually turns into a sort of fluffy, poodle-dog-werewolf during a live television news broadcast!

As in the Underworldpictures, the popular Twilightmovies also chronicle the conflict between a race of vampires and werewolves. Also like the Underworldmovies, the Twilightseries uses computer-generated imagery to accomplish not only the man-into-wolf transformations, but also the monsters themselves. In Eclipse[David Slade, 2010] the werewolves tend to all be very buff, shirtless young men who transform into wolves by leaping into the air.

Hogwarts’ unfortunate Defense Against the Dark Arts teacher Professor Lupin (David Thewlis), introduced in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban[Alfonso Cuarón, 2004] is another werewolf who uses CGI to “morph,” while Jack Nicholson in Wolf[Mike Nichols, 1994] uses a far more subtle, traditional make-up by Rick Baker.

Since the werewolf is here to stay, I suggest taking the excellent advice given by the customers of The Slaughtered Lamb pub in An American Werewolf in London: “Stay on the road. Beware the moon.”