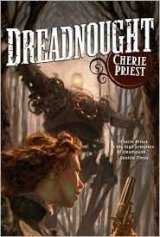

Текст книги "Dreadnought"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 13 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

“Can’t help you there,” she told him, and took another bite.

“I don’t know why I thought you could,” he said with the same accusatory gleam in his eye that Miss Clay had been giving her all week, for exactly the opposite reason.

“Oh, leave it be,” she said with irritation and a half-full mouth. When she’d swallowed the whole thing down, she went on. “What do you want me to say? I told the captain the truth, same as I told you the truth-and I didn’t rat you out to nobody yet, and I’m hoping you’ll treat me the same. My reasons for heading west have nothing to do with the war, and I’m sick of it anyway. I don’t want a whole trainful of folks hating me because of where I worked and where I’m from.”

“So your sympathies lie not in Virginia?” he asked, with a veneer of false innocence.

“Don’t you go putting words in my mouth. I love my country same as you love yours, but I’m not running any mission for my country. I’m no spy, and I’m too tired to fight for anyone but myself right now. Sometimes, I think I don’t have the energy for that, either.”

“Am I supposed to feel sorry for you?”

“I didn’t ask you to,” she snapped. “Same as I didn’t ask you to pull me off the street and feed me. Just because you and me might be sort of on the same team, that’s no excuse for us to hang together.” She took another jab at her plate, knowing there was more to it than that. She mumbled, “You’re gonna get me in trouble, I swear.”

He asked, “And what if I do? What do you think’ll happen to you, if they all find out what you’re keeping quiet?”

She shrugged. “Not sure. Maybe they dump me off at the next stop, in the middle of noplace. I don’t have the money to pay the rest of the way out to Tacoma again. Maybe I get stuck a thousand miles away from where I need to be, with my daddy maybe dying out there. Or, Jesus,” she said suddenly, as it had just occurred to her. “Maybe they’ll arrest me, and say I’m a spy! I can’t prove I’m not.”

“Don’t be ridiculous. They’d arrest mebefore they’d arrest you.”

“Why? Because you’re doing your job in someplace that ain’t Texas?”

“Something like that,” he said in a way that made her want to ask more questions. “Fact is, I think there isa spy on the train-but I’m not sure who yet. That coupler didn’t break all by its lonesome. Someone wants to sabotage the train so the Rebs can catch it, but it sure ain’t me. And I can’t prove it. But I probably look good for it.”

“So what areyou doing on this train? Knowing that being here is asking for trouble?”

He took a deep breath and the last quarter of his sandwich in one bite, and took his time chewing before answering her. He also took a minute to glance around the room, checking the faces he saw for familiarity or malice. Then he asked, “How much do you keep up with the newspapers, Mrs. Lynch?”

“More lately than usually. They gave me something to read while I was coming west.”

“All right. Then maybe you’ve heard about a little problem Texas has right now, with some Mexican fellas who went missing all in a bunch.” He said this conspiratorially, but not so quietly that everyone would try to overhear whatever secret was being told.

“I’ve seen something about it, here and there. Mr. Cunningham aboard the Providence-he gave me the background on the situation.”

“Yeah, I’ll bethe did.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Not a damn thing. I imagine he’s got opinions on it, and I imagine they’re not altogether different from mine. But it’s my job,not my opinion, to sort out what became of the dirty brown bastards and what they’re up to. They went wandering north-”

“To help relocate-”

“They went wandering north,”he talked over her, as if he wasn’t really interested in political discussion. “And they went wandering right off the edge of the map. I’ve been chasing every rumor, snippet of gossip, and wild-eyed fable from every cowhand, cowpoke, rancher, settler, and Injun who’ll stand still long enough to talk to me, and none of it’s making any sense-not at all.”

Honestly curious, she asked, “What are they saying?”

He waved his hand as if to dismiss the whole of it, since none of it could be true. “Oh, they’re saying crazy things-completely crazy things. First off, if word can be believed, they went off course by a thousand miles or so. And I’ve got to tell you, Mrs. Lynch, I’ve known a backwards Mex or two in my time, but I’ve never heard of one dumb enough to go a thousand miles off course in the span of a few months.”

“That doessound unlikely.”

“It goes well beyond unlikely. And I don’t think Mexico knows what’s happened to ’em either-that’s what really gets me. Likewise-and I’m in a pretty secure position to know-the Republic didn’t touch ’em. Whatever happened happened somewhere out in the West Texas desert hill country, and then something sent those men on some other bizarre quest-”

“All the way to Utah?” she interjected.

Derailed, he stopped and said, “Utah? How’d you know that?”

“Because you told me that’s how far you were riding the other day. The Utah territory’s a long piece away from West Texas, I’d think.”

“Amazingly far,” he confessed. “But that’s what the intelligence is telling us. Something strange happened, and the group shifted direction, drifting north and west. The last reports of Mexican soldiers have come from the Mormon settlements out there-you know, them folks who have all the wives and whatnot. The Mormons may be swamp-rat crazy themselves, for all I know, but they’re scared to death.”

“Of a legion of soldiers? Can’t say as I blame them. Lord knows it’d give me a start to find them in my backyard.”

“That’s not all there is to it, though,” he said, and he shook his head some more, as if there was simply no believing what he was about to say. “Reports say these Mexis have gone completely off their rockers. I heard,” and he finally leaned forward, willing to whisper, “that they’ve started eating people.”

“You shut your mouth!” Mercy exclaimed.

“But that’s what people say-that they’re just mad as hatters, and that something’s gone awful wrong with them. They act senseless, like their brains have leaked right out of their heads, and they don’t talk-they don’t respond to anything, English or Spanish. Mrs. Lynch, people are going to panicif word gets out and nothing gets done about it!”

“Well . . .” Mercy tried to process the information and wasn’t sure how to go about it, so she racked her brain and tried to think of something logical. “Do you think it’s some kind of sickness, like rabies or something? People with rabies will do that, sometimes; bite people-” And she cut herself short, because saying so out loud reminded her of the Salvation Army hostel.

The ranger said, “If these fellas have some kind of disease, and it’s so catching that a whole legion of ’em came down with it and went insane, that’s not exactly a comforting thought. Whatever’s going on, we need to contain it, and maybe . . . investigate it. Figure out what’s wrong, and figure out if we can do something about it. But I’ll be damned right to hell if I have the faintest idea what’s going on,” he said before stuffing bread and potatoes into his mouth.

She said, “I wonder if it’s got something to do with sap.”

“What, like tree sap? Oh, wait, no. You mean that stupid drug the boys on the front are using these days? I don’t see how.”

“I wouldn’t have believed it either, till I wound up in Memphis. I saw some fellas there, some addicts who’d used the stuff almost to death. They looked . . . well, like you said. Like corpses. And one of ’em tried to bite me.”

“An addict trying to bite a nurse ain’t quite the same as cannibalism.”

She frowned and said, “I’m not saying it is. I’m only saying it looks the same, a little bit. Or maybe I’m just crackers.” Then she abruptly changed the subject, asking before she had time to forget, “Say, you don’t know anyplace around here where I could send a telegram, do you?”

“I’d be surprised if there wasn’t a Western Union office at the station. You could ask around. Why? Who’re you reporting to, anyway?”

“Nobody but my mother. And the sheriff out in Tacoma, I guess. I’m just trying to let folks know that I’m still alive, and I’m still on my way.”

When the meal was over, she thanked him for it and went walking back to the station, where she did indeed find a Western Union and a friendly telegraph operator named Mabel. Mabel was a tiny woman with an eye-patch, and she could work a tap at the speed of lightning.

Mercy sent two messages, precisely as she’d told the ranger.

The first went to Washington, and the second went to Virginia.

SHERIFF WILKES I AM WESTBOUND AND PRESENTLY IN KANSAS CITY STOP EXPECT ME WITHIN A FEW WEEKS STOP WILL SEND MORE WORD WHEN I GET CLOSER STOP HOPE ALL IS WELL WITH MY FATHER STOP

DEAR MOMMA PLEASE DO NOT BE ANGRY STOP I’M GOING WEST TO VISIT MY DADDY WHO MAY BE DYING STOP IT IS A LONG STORY AND I’LL TELL IT TO YOU SOMETIME STOP DO NOT WORRY I HAVE MONEY AND TRAIN TICKETS AND ALL IS FINE STOP EXCEPT FOR I GUESS I SHOULD TELL YOU PHILLIP DIED AND I GOT THE WORD AT THE HOSPITAL STOP GO AHEAD AND PRAY FOR ME STOP I COULD PROBABLY USE IT STOP

After she’d paid her fees, Mercy turned to leave, but Mabel stopped her. “Mrs. Lynch? I hope you don’t mind my asking, but are you riding on the big Union train?”

“Yes, I am. That’s right.”

“Could I bother you for a small favor?” she asked.

Mercy said, “Certainly.”

Mabel gathered a small stack of paper and stuffed it into a brown folder. “Would you mind dropping these off at the conductor’s window for me?” She gestured down at her left leg, which Mercy only then noticed was missing from the knee down. “I’ve got a case of the aches today, and the stairs give me real trouble.”

“Sure, I’ll take them,” Mercy said, wondering what terrible accident had so badly injured the woman’s body, if not her spirit. She took the telegrams and left the office with Mabel’s thanks echoing in her ears, heading down to the station agent’s office and the window where the conductors collected their itineraries, directions, and other notes.

Down at that window, two men were arguing over tracks and lights. Mercy didn’t want to interrupt, so she stood to the side, not quite out of their line of sight but distant enough that she didn’t appear to be eavesdropping. And while she waited for them to finish, she did something she really shouldn’t have. She knew it was wrong even as she ran her finger along the brown folder, and she knew it was a bad idea as she peeled the cover aside to take a peek within it. But she nonetheless lifted a corner of the folder and glanced at the sheets there, realizing that they weren’t all notes for the conductor: some were telegrams intended for passengers.

Right there on top, as if Heaven itself had ordained that she read it, she saw a most unusual message. At first it made no sense whatsoever, but she read it, and she puzzled over it, and she slapped the folder shut when the men at the window ceased their bickering and went their separate ways.

It said,

CB ALERT STOP STALL AT KC AS LONG AS POSSIBLE STOP SHENANDOAH APPROACHING FROM OC TOP SPEED STOP SHOULD CATCH TRAIN BEFORE ROCKIES STOP CONFIRM OR DENY CABOOSE BY TOPEKA IF POSSIBLE STOP SEND WORD FROM THERE STOP

Alas, her workmanlike reading skills moved too slowly to give it a second, more through inspection before the conductor spotted her. Once he did, she approached him, to keep from looking too guilty. She handed the folder to the man, bid him good evening, and returned to her hotel room feeling deeply perplexed and revisiting the message in her mind.

By the time she undressed for bed, she’d guessed that “OC” might be Oklahoma City, since “KC” was so obviously Kansas City. She didn’t know what the “Shenandoah” was, but if it was traveling at top speed, and trying to “catch” the Dreadnought,she was forced to assume that it must be a mighty piece of machinery indeed. And what did “CB” mean? Was it someone’s initials? A code name? A sign-off?

“Shenandoah,” she whispered to herself. A southern name, for southern places and southern things. “Could be a unit or something.” She turned over, unable to get very comfortable on the cheap bed, yet grateful enough for it that she wanted to stay awake and enjoy the fact that it wasn’t moving. So she stayed up and asked the washbasin against the wall. “Or another train?”

The last thing that rolled through Mercy’s mind before her eyes closed and stayed that way was that Ranger Korman was right.

Someone on board was a Rebel spy.

It wasn’t her, and she didn’t think-based on their conversation over supper-that it was the ranger, either. So whom did that leave?

She sighed, and said, “Could be almost anyone, really.”

And then she fell asleep.

Thirteen

Come morning, Mercy stood on the train station platform with her fellow passengers, waiting for the opportunity to board once more. She noticed a few absences, not out of nosiness, but simply because she’d become accustomed to seeing the same people day in and out for the previous week. Now she saw new faces, too, looking curiously at the awe-inspiring engine and discussing amongst themselves why the train required such an elaborate thing.

The conductor overheard the questions, and Mercy listened to his answer, though she didn’t know how much of it to believe. “True enough, this is a war engine,” he said, patting at the boiler’s side with one gloved hand. “But that doesn’t mean this is a war operation. We’re sending some bodies of boys from the western territories back home, and while we’re at it, we’re bringing this engine out to Tacoma to retrofit it with a different sort of power system.”

One curious man asked, “Whatever do you mean?”

“At present, she’s running on a two-fuel system: diesel and coal steam. She’s the only Union engine of her kind, though I understand the Rebs use diesel engines pretty regularly. In Tacoma, we’re going to see if we can retool her to use straight diesel, like theirs. It’ll give us more power, better speed, and a lighter payload if we can work it out.”

Mercy had a hard time figuring how a liquid fuel would be any lighter than coal, but she was predisposed to disbelieving him, since his story was different from the St. Louis station agent’s-and now that she’d talked to the ranger, and now that she’d seen the telegram that wasn’t meant for her eyes. She’d never quite bought that the war engine was on a peaceful mission, and the longer she looked at it, the more deeply she felt that the train’s backstory was a lie.

Then something dawned on her, seeming so obvious that she should’ve thought of it before. She did her best not to draw anyone’s attention by dashing. Instead, she shuffled back toward the rear end of the train, to the caboose, and the bonus car that trailed bleakly behind with all its windows painted over. There was a guard standing on the platform that connected it to the caboose, but no one else was paying it any mind.

Mercy had no means of telling whether or not anything had come or gone, or been loaded or unloaded. But she spied an older negro porter, and she quietly accosted him. “Excuse me,” she said, turning her body to keep her face and her voice away from the guard, who wasn’t watching her, but might’ve been listening.

“Yes ma’am. How can I help you?”

“I was wondering . . . have those fellows opened that car at all? Taken anything off it, or put anything inside it?”

“Oh noma’am,” he said with a low, serious voice. He shook his head. “None of us are to go anyplace near it; we was told as soon as it stopped that nobody touches the last car. I even heard-tell that some of the soldiers got a talking-to for getting too close or peeking in the windows. That thing’s sealed up good.”

She said, “Ah,” and thanked him for his time before wandering back to the passenger cars, turning this information over in her mind as she went. If the train was transporting war dead home to rest, why weren’t any of them ever dropped off? She wondered who on earth she could possibly share her suspicions with, then saw the ranger leaning up against one of the pillars supporting the station overhang, an expression on his face like he’d been licking lemons.

“Mr. Korman,” she said. He must have heard her, but he didn’t look at her until she was standing in front of him.

“What?” he asked.

“And a fine morning to you, too, sir,” she said.

“No, it isn’t.”

She asked, “How’s that?”

He spit a gob of tobacco juice in an expert line that ended with a splatter at the foot of the next pillar over. He didn’t point, but he nodded his head toward a spot by the train where two dark-haired men were chatting quietly, their backs to Mercy and Horatio Korman. “You see that?”

“See what? Those two?” The moment she said this, one of them pivoted on a sharp-booted heel, casting a wary glance across the crowd before returning to his soft conversation. His face had a shape to it that might’ve been part Indian, with a strong profile and skin that was a shade or two darker than her own. He had thick black eyebrows that had been groomed or combed, or merely grew in an unlikely but flattering shape. He and his companion were not speaking English, Mercy could tell, even though she couldn’t make out any of their particular words. Their chatter had a different rhythm, and flowed faster-or maybe it only sounded faster, since the individual syllables meant nothing to her.

“Mexicans.”

Temporarily knocked off topic, Mercy asked, “Really? What are they doing here? They’re going to ride the train with us?”

“Looks like it.”

She thought about this, and then said, “Maybe you ought to talk to them. Maybe they’re here for the same reason as you.”

“Don’t be ridiculous.”

“What’s so ridiculous about that? You want to know what happened to their troops; maybe theywant to know what happened to them, too. Look at them: they’re wearing suits, or uniforms of some sort. Maybe they’re military men themselves.” She squinted, not making out any insignia.

“They ain’t no soldiers. They’re some kind of government policemen or somesuch. You’re probably right about what they’re after, but there’s nothing they can contribute to the search.”

She demanded, “How do you figure that?”

“Like I told you the other night, they don’t know any more about it than we do. I’ve got all the best information at hand, and I’ve busted tail and greased palms to get it. I’m closer to learning the truth than anybody on the continent, and that includes the emperor’s cowpokes.”

She gave a half shrug and said, “Well, they’ve gotten this far, same as you. They can’t be all useless.”

“Hush up, woman. They’re trouble, is what they are. And I don’t like trouble.”

“Something tells me that’s not altogether true.”

His mustache twitched in an almost-smile, like when he’d discovered the guns under her cloak. “You might have me there. But I don’t like seeing them. No good can come of it.”

“I don’t think I’ve ever met any Mexicans before.”

“They’re tyrants, and imperialists, every last one of them.” If he’d been holding any more tobacco in his lip, he no doubt would’ve used it to chase the sentence out of his mouth.

“And I guess you’ve talked to every last one of them, to be so sure of that.”

The ranger reached for his hat to tip it sarcastically and, no doubt, walk away from the conversation, but Mercy stopped him by saying, “Hey, let me ask you something. You know anything about a . . . a train?” She went with her best guess. “Called the Shenandoah?”

“Yeah, I’ve heard of it.”

“Is it . . .” She wasn’t sure where she was headed, but she fished regardless. “Is it a particularly fasttrain?”

“As far as I’ve heard. Rolls for you Rebs, I think. Supposed to be pretty much the swiftest of the swifties,” he said, meaning the lightweight hybrid engines that were notorious for their speed. They’d been designed and mostly built in Texas, some of them experimental, as the Texians had searched for more ways to make use of their oil.

She stood there, nodding slowly and wondering how much she should tell him. He’d already made plain that he didn’t care what the Rebs wanted with the train. Then again, he might’ve been lying, or he might care if he thought there were spies on board. Anyway, it wasn’t like she had anybody else to tell.

While she was still pondering, he said, “What makes you ask, anyway?”

She would’ve answered, too, if the whistle hadn’t chosen that precise moment to blow, causing the few children present to cover their ears and grimace, and the milling adults to cluster tighter together, pressing forward to the passenger cars in anticipation of boarding or reboarding.

“Never mind,” she said instead. “We can talk about it later.”

She walked away from him and joined the press of people. As the crowd thickened, she was more and more likely to be spotted conspiring with the ranger; and although she was the only one who knewhe was a ranger, everyone had already gathered that he was a Texian, and she didn’t want to join him as a pariah. She understood why he would prefer to keep his status as a law enforcer quiet, though: military men like to have a hierarchy. They wouldn’t have liked to think that someone outside that hierarchy was hanging around, wearing guns, and from a strictly legal standpoint, they wouldn’t have any authority over him. But they could make his life difficult, especially in such a confined mode of transport.

Back on board the train, Mercy was surprised to note that Mrs. Butterfield and Miss Clay had beaten her to the compartment. She was even more surprised, and openly curious, to note that the two Mexican men had been assigned to her own car. The two ladies opposite her were not whispering, just conversing about the newcomers in their normal voices.

“I heard them speaking Spanish,” said Mrs. Butterfield. “Obviously I don’t understand a word of it, but that one fellow there, the taller one, he looks almost white, doesn’t he?”

“He might bewhite,” Theodora Clay pointed out. “There are still plenty of Spaniards in Mexico.”

“Why? Wasn’t there some kind of . . . I don’t know . . . revolution?” Mrs. Butterfield asked vaguely.

Her niece replied, “Several of them. But I wonder why they’re on board, heading north and west? That sounds like the wrong direction altogether, don’t you think? They aren’t dressed for the weather, I can tell you that much.”

Mercy suggested, “Why don’t you ask them, if you really want to know?”

Mrs. Butterfield shuddered, and gave Mercy a look that all but said, Good heavens, girl. I thought I knew you!Instead, she told the nurse, “I’m sure I’m not interested in making any strange new friends on this occasion. Besides, they probably don’t speak English. And they’re all Catholics anyway.”

“I bet they dospeak English,” Mercy argued. “It’s pretty hard to find your way around if you don’t speak the language, and they’ve made it this far north all right.”

Miss Clay arched an eyebrow, lifting it like a dare. “Why don’t yougo chat them up, then?”

Mercy leaned back in her seat and said, “You’re the one who’s dying to know. I was only saying that if you were thatdesperate, you could just ask.”

“Why?” Miss Clay asked.

Mercy didn’t understand. “Why what?”

“Why aren’t you interested? I think interest is positively natural.”

She narrowed her eyes and replied, “I’m inclined to mind my own business, is all.”

But later on that day, nearly up to evening, Mercy found her way back to the caboose in search of supper, and there she found the two Mexicans seated at a table with Captain MacGruder and the injured (but relatively able-bodied) Morris Comstock. Morris smiled and waved, and the captain dipped his hat at her, which gave her the perfect excuse to join them. She ordered a cup of tea and some biscuits with a tiny pot of jam and carried them over to the seat the men had cleared in her behalf.

“Gentlemen,” she said, settling herself. She made a point of making eye contact with the two Mexicans, for the sheer novelty if nothing else. They seemed to find her presence peculiar, but they behaved like the gentlemen she’d accused them of being, and murmured greetings in response.

“Mrs. Lynch,” said the captain. “Good to see you again. We were just having a little talk with these two fellows here. They’re from Mexico.”

Morris said, “We were giving them a friendly warning, too. About that Texian riding in the sixth car. He’s a mean-looking bastard, and I hope he don’t make problems for these folks.” However, he said it with a gleam that implied he might not be too disappointed at the chance to reprimand the ranger.

MacGruder cleared his throat and said more diplomatically, “I understand you’re acquainted with the Republican in question. Came out on the same riverboat, to St. Louis, is that right?”

“Yes, that’s right. I don’t believe it’s come up before, though. How did you know?”

“Miss Clay might have mentioned it, in passing.”

“I see.”

“Señora,” said the darker of the two men, the one she’d seen at the station with the uncommonly tidy eyebrows. “Please allow me to introduce myself: I am Javier Tomás Ignacio Galeano.” He said the names in one long string that sounded like music. “And this is my associate, Frederico Maria Gonsalez Portilla. We are . . . inspectors. From the Empire of Mexico. We do not intend to cause a stir aboard this train; we are only in the process of discovering what has happened to a lost legion of our nation’s soldiers.”

Mercy was glad his English was so good. She didn’t need to strain to understand him, and she didn’t feel that idiotic compulsion to speak loudly. She said, “I’ve heard about that-it’s in the newspapers, you know.”

His fellow inspector said, “Yes, we are aware that it has made your papers. It is a great mystery, is it not?”

“A great mystery indeed,” she agreed, feeling a tiny thrill over the conversation with a foreigner. She’d known plenty of northerners and southerners, but she’d never met anybody who was from a-whole-nother countrybefore. Except Gordon Rand, and he didn’t hardly count.

Inspector Galeano fretted with his napkin and said, “If only we knew what had happened, out in the west of Tejas.” He called the Republic by the name it’d worn as a Mexican state.

“What do you mean?” she asked.

He told her, “Something occurred, and it sent them off course, up past the low, hot country and north into the mountains. We have learned that they made it as far as the territory of the . . . of the . . .” He searched his English vocabulary for a word, but failed to find it.

“Utah,” Morris Comstock provided. “Where the Mormons live, with all them wives.”

“Mormons, yes. The religious people. Some of them have made reports . . . terriblereports.”

Mercy almost forgot that she wasn’t supposed to know any of this, but managed to stop herself from exclaiming about the cannibalism before anyone could ask her how she’d come by the information. Instead, she said, “I’m sorry to hear that. Do you have any idea what happened? Do you think the Texians did something . . . rash?”

Inspector Portilla’s forehead crinkled at the use of rash,but he gleaned the context and said, “It’s always possible. But we do not think that is the case. We have had reports that some Texians are implicated as well.”

“What kind of reports? Terriblereports?” she asked.

“Equally terrible, yes. We believe”-he exchanged a glance with Inspector Galeano, who nodded to affirm that this was safe to share-“that there may be an illness of some sort.”

“That’s possible,” Mercy said sagely. “Or a . . . a poison, or something.” Then, to forestall any questions about her undue interest, she said, “I’m a nurse. This stuff’s interesting to me.”

“A nurse?” said Inspector Galeano. “We were told there would be a doctor on the train, but we’ve heard of no such-”

Morris Comstock interrupted. “We were supposed to pick one up in Kansas City, but he never showed. So now we’re supposed to have one in Topeka, maybe. I swear, I think they’re just telling us tales.”

The captain crossed his arms, leaned back, and said to the Mexicans, “Mrs. Lynch is the one who patched up poor Morris here, when he got winged during that raid.”

Inspector Galeano wore a look of intense interest. He bent forward, laid one arm on the table, and gestured with the other hand. “We only developed this idea very recently, from inteligenciathat found us in Missouri. But perhaps I can ask you this question-and I hope you will not consider me . . .” He shuffled through his vocabulary for a word, then found it. “Rude.”

“Fire away,” she told him, hoping that she looked the very picture of enthusiastic innocence.

He said, “Very good. These are the facts as we understand them: A partial force of soldiers was sent from a presidio in Saltillo. They met with commanders and acquired more personnel in El Paso. At the time, their numbers were approximately six hundred and fifty. They traveled east, toward the middle of the old state, near Abilene. From there they were to march on to Lubbock, and up to the settlement at Oneida-called Amarilloby your people. By then they had added another hundred settlers to their number. But they never reached Lubbock.”

She observed, “That many people don’t just vanish into thin air.”

“Nor did these,” he agreed. “They’ve been glimpsed, and there are signs of their passing, but the signs are . . .” He retreated to his original description, finding none other that suited the gravity of the situation. “ Terrible. They wander, driven by the weather or whatever boundaries they encounter, bouncing from place to place, and . . . and . . . it is like a herd of starving goats, everywhere they go! They leave nothing behind-they consume all food, all plants and crops, all animals . . . and possibly . . . all the peoplethey meet!”

“People!” Mercy gasped for dramatic effect, and squeezed one of her biscuits until it fragmented in her hand. She let its crumbs fall to the plate, and left them unattended.

“Yes, people! The few who have escaped tell such stories. The missing soldiers and settlers have taken on an awful appearance, thin and hungry. Their skin has turned gray, and they no longer speak except to groan or scream. They pay no attention to their clothing, or their bodies; and some of them bear signs of violent injuries. But these wounded men-and women: as I said, there are settlers among them-they do not fall down or die, though they looklike they are dead. Now, tell me, Nurse Lynch, do you know of any poison or illness that can cause such a thing?”