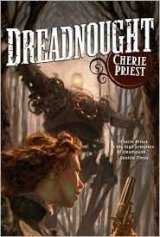

Текст книги "Dreadnought"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 5 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

Rand added, “Or perhaps they’re slow readers.”

Mercy was out of her chair now, invigorated by the prospect of having something to do. She told Ernie, “Come sit over here, by me. And give me your hand.”

He joined her at her seat and sat patiently while she rummaged through her sack.

“Everybody hang on to something. We’re losing altitude,” the first mate announced.

The captain amended the announcement to include, “We’re going down, but we aren’t crashing. Brace yourselves as you can, but I repeat, we are not crashing. The steering’s all but gone out, that’s all, so I can raise or lower us, but not point us in any direction.”

“Are we behind southern lines?” someone other than Mercy asked, but she didn’t see who’d raised the question again.

“Yes,” the captain’s tone of certainty was an outright lie, but he stuck to it. “We’re just setting down, but we might take a tree or two with us. Estimated time to landing, maybe two or three minutes-I’ve got to take her down swift, because we’re drifting back the other way.”

“Oh, God,” said the old lady.

“Don’t holler for him yet,” Mercy muttered. “It might not be as bad as all that. Ernie, let me see your hand.”

“We’ve only got a couple of minutes-”

“I only need a couple of minutes. Now hold still and let me look.” By then, she’d found her bandage rolls. She tore off a portion of one, and used it to wipe the area clear enough to see it better. It wasn’t all cuts, and it wasn’t all burns. In the very dim light that squeezed in through the windows, she could see it was a blending of both. Mercy would’ve bet against him ever having proper use of his mangled index finger again; but the wound wouldn’t be a killing one unless it took to festering.

“How bad is it?” he asked her, both too nervous too look, and too nervous to look away. He blinked, holding his head away so he couldn’t be accused of watching.

“Not so bad. Must hurt like the dickens, though. I need to wash it and wrap it up.”

“We only have-”

“Hold it up, above your shoulder. It’ll bleed slower and hurt less that way,” she urged, and dived back into the bag. Seconds later, she retrieved a heavy glass bottle filled with a viscous clear liquid that glimmered in the moonlight and the feeble glow from the lanterns outside.

He said, “We’re going down. We’re reallygoing down.”

He was looking out the window beside her head. She could see it, too-the way the clouds were spilling past. She tried to ignore them, and to ignore the throat-catching drop of the craft.

“Don’t look out there. Look at me,” she commanded. Meeting his eyes she saw his fear, and his pain, and the way he was so pallid from the injury or the stress of acquiring it. But she held his eyes anyway, until she had to take his hand and swab it off with a dampened bandage.

The Zephyrwas not falling, exactly. But Mercy could not in good conscience say that it was “landing” either. Her stomach was up in her mouth, nearly in her ears, she thought; and her ears were popping every time she swallowed. If she didn’t concentrate on something else, she’d start screaming, so she focused on the bleeding, burned hand as she cleaned it, then propped Ernie’s elbow on the headrest to keep it upright while she fumbled for dry bandages.

The old man leaned forward and threw up on the floor. His wife patted at his back, then felt around for any bags or rags to contain or clean it. Finding none, and lacking anything better to do, she returned to the back-patting. Mercy couldn’t help them, so she stayed with Ernie, wrapping his still-bleeding hand and doing it swiftly, as if she’d been mummifying hands for her whole life. She did it like the world was ending at any minute, because for all she knew, it might be.

But things could be worse. No one was shooting at them.

She told Ernie, “Hold it above your heart and it won’t throb so bad. Did I tell you that already?”

“Yes ma’am.”

“Well, keep doing it.” She gasped then as the ship gave a lurch and a heave as if its own stomach were sinking and rising. The captain told everyone to “Hang on to something!” but there was no something handy except for the seat.

Ernie went for chivalry, flinging his right arm over Mercy’s shoulder and pulling her under his chest; she ducked there, and wrapped her left arm around his waist. She closed her eyes so she couldn’t see the ground rearing up out the window, not even out of her peripheral vision.

The next phase was not as sudden as she’d expected. It sneaked up on her, taking her breath away as the Zephyrsliced through treetops that dragged it to a slower pace, then snagged it and pulled it down to the ground with a horrible rending of metal and rivets. The ship sagged, and dipped, and bounced softly. No one inside it moved.

“Is it-?” asked the old woman whose name Mercy still didn’t know. “Are we-?”

“No!” barked the captain. “Wait! A little-”

Mercy thought he might’ve been about to say farther,because something snapped, and the craft dropped about fifteen feet to land on the ground like a stone.

Though it jarred, and made Mercy bite her tongue and somehow twist her elbow funny, the finality of the settled craft was a relief-if only for a minute. The ship’s angle was all wrong, having landed on its belly without a tethering distance. From this position, they lacked the standard means of opening the ship to let them all go free. A moment of claustrophobic horror nearly brought tears to Mercy’s eyes.

Then she heard the voices outside, calling and knocking; and the voices rode with accents that came from close to home.

Someone was beating against the hull, and asking, “Is everybody all right in there? Hey, can anybody hear me?”

The captain shouted back, “Yes! I can hear you! And I think everyone is . . .” He unstrapped himself from his seat-the only seats with straps were in the cockpit-and looked around the cabin. “I think everyone is all right.”

“This a civvy ship?” asked another voice.

“Says so right on the bottom. Didn’t you see it coming down?”

“No, I didn’t. And I can’t read, nohow.”

Their banal chatter cheered Mercy greatly, purely because it sounded normal-like normal conversation that normal people might have following an accident. It took her a few seconds to realize that she could hear gunfire in the not-very-distant distance.

She disentangled herself from Ernie, who was panting as if he’d run all the way from the clouds to the ground. She nudged him aside and half stepped, half toppled out of her seat, bringing her bags with her. The crewman came behind, joining the rest of the passengers who were trying to stand in the canted aisle.

“There’s an access port, on top!” the captain said to his windshield.

That’s when Mercy saw the man they were speaking to outside, holding a lantern and squinting to see inside. He was blond under his smushed gray hat, and his face was covered either in shadows or gunpowder. He tapped one finger against the windshield and said, “Tell me where it is.”

The captain gestured, since he knew he was being watched. “We can open it from inside, but we’ve got a couple of women on board, and some older folks. We’re going to need some help getting everyone down to the ground.”

“I don’t need any help,” Mercy assured him, but he wasn’t listening, and no one else was, either.

Robert was already on his way up the ladder that he and Ernie had both scaled earlier, though he dangled from it strangely, so tilted was the ship’s interior. He wrapped his legs around the rungs and used one hand to crank the latch, then shoved the portal out. It flopped and clanged, and was still. Robert kept his legs cinched around the ladder and braced himself that way, so he could work his arms free.

He reached down to the passengers and said, “Let’s go. Let’s send some people up and over. You. English fella. You first.”

“Why me first?”

“Because you ain’t hurt, and you can help catch the rest. And Ernie’s got his hand all tore up.”

“Fine,” Gordon Rand relented, and began the tricky work of climbing a ladder that leaned out over his head. But he was game for it, and more nimble than the tailored foreign clothes let on. Soon he was out through the portal and standing atop the Zephyr,then sliding down its side, down to the ground.

Mercy heard him land with a plop and a curse, but he followed through by saying to someone, “That wasn’t so bad.”

That someone asked, “How many are there inside?”

“The captain, the copilot, and half a dozen passengers and crew. Not too many.”

“All right. Let’s get them down, and out.”

Someone else added, “And out of here. Bugle and tap says the line’s shifting. Everybody’s got to move-we might even be in for a retreat to Fort Chattanooga.”

“You can’t be serious!”

“I’m serious enough. That’s what the corporal told me, anyway.”

“When?”

“Just now.”

“Son of a bitch. They’re right on top of us!”

Mercy wished she could see the speakers, but she could see only the frightened faces of her fellow passengers. No one was moving yet; even Robert was listening to the gossip outside. So she took it upon herself to move things along.

“Ma’am? Sir?” she said to the older couple. “Let’s get you up out of here next.”

The woman looked like maybe she wanted to argue, but she didn’t. She nodded and said, “You’re right. We’ll be moving slowest, wherever we go, or however we get there. Come along, dear.”

Her dear said, “Where are we going?”

“Out, love.” She looked around. “I can make it up on my own, but he’ll need some assistance. Captain? Or Mr. . . . Mr. First Mate?”

“Copilot,” he corrected her as he climbed into the cabin. “I’d be happy to help.”

Together they wrested and wrangled the somewhat reluctant old man and his insistent wife up the concave ladder and out the hatch. Then went the clubfooted student; and then Ernie, with a little help from Robert; and then Mercy, who couldn’t get off the thing fast enough. Finally, the other student and the rest of the crew members extracted themselves, leaving the Zephyran empty metal balloon lying tipped and steaming on the ground.

Five

A message had come and gone to someone, somewhere, and two more gray-uniformed men came running up to the group, leading a pair of stamping, snorting horses and a cart. The man holding the nearest horse’s lead said to the group, “Everyone on board. Line’s shifting. Everybody’s got to go while the going’s good.”

“ Whereare we going?” demanded Gordon Rand even as he hastened to follow instructions.

He was helping the elderly woman up the back gate and into the makeshift carriage when the second newcomer replied. “Fort Chattanooga.”

“How far away is that?” he inquired further.

“Better part of thirty miles.”

Larsen exclaimed, “We’re going to ride thirty miles in that?”

And the first man answered, “No, you’re going to ride twomiles in this, and then the rail will take you the rest of the way.”

“We’re outside Cleveland? That’s what the captain said,” Mercy said, fishing for confirmation of anything at all.

“That’s right.” The second Reb had hair so dark, it gleamed blue in the light of the lanterns. He gave her a wink and a nod that were meant to be friendly. “But come on, now. Everybody aboard.”

The captain lingered by the Zephyrwhile the elderly couple settled in. The students climbed over the cart’s edge behind them. “I need to reach a telegraph. I’ll have to tell my dispatcher that the ship is down, and give them coordinates to retrieve it,” the captain said plaintively.

But Mercy saw the artillery flashes and heard the earsplitting pops of gunfire through the trees, and she answered with a guess before anyone else could say it. “There won’t be anything left of her by morning.”

“One bullet,” Gordon Rand said softly from his spot in the cart. “That’s all it’ll take, on her side, with her tanks exposed like that.”

“Damn straight,” said the blond who’d first communicated through the windshield. “All the more reason to hit the road, sooner rather than later. We don’t want to be anywhere near her when she goes up in flames. She’ll take a quarter mile of forest and everything in it.”

Ernie gave a yelp when he was hauled onboard, prompting the dark-haired private-Mercy thought he was a private, anyway-to ask if anyone else was hurt. “Does anyone need any help? Is this everybody?”

“This is everybody,” the captain confirmed. “We weren’t traveling full. And the line wasn’t supposed to move this far south; they told me at Richmond that it hadn’t come this far,” he complained even as he climbed aboard to join the rest of his passengers and crew.

The private reached for the reins and held on to them as he climbed up onto the steering seat. His companion leaped up to take a spot beside him, and with a crack of the reins, the cart was turning around to go back the way it had come. The private continued, raising his voice to make himself heard over the background roar of fighting, “We were holding ’em back real good, up until tonight. We’d cut ’em off from their cracker line, and the Chatty trains were keeping us in food and bullets, while they were running low on both.”

Mercy didn’t see the blond soldier who’d been first on the scene-he had either stayed on the scene or gone in some other direction. The other blond had left the driving to the private, and was scanning the trees with a strange scope layered with special lenses, the nature of which Mercy could only guess.

The captain asked, “Then what happened, man? What turned the tide so fast that the taps couldn’t catch up?”

Over his shoulder, the driver said, “They brought in an engine. That thing tore right through our blockades like they were made of pie dough. Killed a score every half a mile. Eventually we just had to let them have it.”

Mercy said, “An engine? Like a train engine? I don’t understand.”

The blond lowered his scope and said, “The rail lines around here, they run crisscross, all over each other, every which-a-direction. We commandeered the switches and posted up our lads to keep the Yanks’ cracker line squeezed off shut. But then they brought-”

The private interrupted him. “The Dreadnought. That’s what they call it.”

“My CO said he thought the damn thing was back east, over in D.C., watching over the capital after our rally there last month. But no! Those bastards brought that unholy engine all the way out here, and it mowed us right down. They took back their line in under an hour, and now they’re pushing us back. They’re pushing us back good,” he emphasized, and drew the lenses back up to his face. “Veer us left, Mickey,” he said to the driver. “I don’t like the look of the smoke kicking up to the east.”

“We’re going to run out of road.”

“Better that than running into artillery, eh?”

The Zephyr’s copilot was sour looking, squatting next to the captain. He asked, “How do you know it’s artillery? I can’t see a damn thing past the lanterns on the cart.”

The navigator gave the copilot a look like he must be the stupidest man alive and waggled his scope, with its myriad jingling lenses. “They’re the latest thing. They ain’t perfect, but they do all right.” One more glance through the lenses, and he said, “But we gotta get rid of our lights or they’ll spot us over there. Mickey, the lanterns. Kill ’em. Kill all of ’em.”

“Clinton, I swear to God-”

“I’m not asking you a favor, you nitwit, I’m telling you-”

“I’m working on it!” Mickey cut him off. “Who’s holding the other one?”

“I am,” the captain said. “And I’m trimming the wick right now.”

“Not enough,” insisted Clinton. “Turn it off. Damp the whole thing down.”

Mickey’s lantern had already been snuffed, so when the captain reluctantly killed the light he held, the forest swallowed them whole. The horses slowed without being told, whinnying and neighing their displeasure and their nervousness. Mickey told them, “Hush up, you two.” Then, to the people in the back, he said, “Down, all of you. Get as low as you can go. Cover your heads.”

The old man, who had been silent against his wife thus far, instead asked, in a voice far too loud for anyone’s comfort, “Why did it get so dark and quiet?”

Gordon Rand slapped his hand firmly over the old man’s mouth and whispered, “Because none of us want to die. Now contain yourself, sir.”

The old man did not so much contain himself as begin to giggle, but it was a quiet giggle, and no one chided him for it. All of them crouched down low, hunkering as deeply as possible against the floor of the cart as it rattled, jostled, and bounced them along the nearly invisible road between the trees . . . then off to the left where the road was less distinct, and rougher. It was also harder to bear for the folks whose knees, elbows, and ribs battered against the wood-slat bottom.

Nearby, a tree exploded, casting splinters as large as arms and legs through the darkness. The old woman muffled her own scream, and everyone else flattened even lower, as if they could meld themselves with the floor of the cart.

Mickey groaned. When Mercy looked up, she could see something dark and shiny all over his face and side, but he stayed upright and flipped the reins at the horses, yelling “Yah!”

The elderly man, absent Gordon Rand’s hand over his mouth, exclaimed, “I thought we were supposed to be quiet!”

But there was no being quiet anymore; it wouldn’t do any good at this point, and the horses and cart were barreling-kicking back to the main road where travel was faster, if more exposed. Another tree nearby was blown to bits with a sound like the whole world falling down. As the echo of it faded, Mercy’s ears were ringing, and there was a tickle in her nose, of sawdust or vibration, then a knock against her head as a rock in the road launched the cart higher, then dropped it to the ground again with a clap that fractured the back axle.

“Oh, Jesus!” Mercy gasped, not that she thought He might be listening. Beneath her body, she could feel the sway and give and tug of the weakened wheels, and an added quiver to the cart’s retreat.

“Mickey!” Clinton cried.

Mercy looked up just in time to see him wobble back and forth to the rhythm of the fleeing horses, and begin to fall. Clinton grabbed him and jerked him back onto the seat, but couldn’t hold him steady; so the nurse leaped from her crouch and snagged the driver, pulling him back into the cart and right on top of herself, since there was no chance to maneuver him and no steady spot to put him down.

Clinton seized the reins.

With the help of Gordon Rand and the students, Mercy rolled Mickey over and patted him down in the darkness. She could see almost nothing, but she could feel a copious, warm dampness. “Captain!” she said. “Bring that lantern over here!”

“We’re supposed to keep it turned off!”

“Turn it up, just a spark. I need to see. And I don’t think it matters now, nohow.” She took the lantern from his hand and twisted the knob just enough to bring it up to a pale glow, barely enough illumination to help. The light swung wildly back and forth from its wire handle, and the whole scene looked unreal, and hellish, and rattled. “He’s bleeding bad.”

“Not thatbad . . . ,” he slurred, and his eyes rolled up in his head.

Black-haired Mickey had lost a chunk of that pretty mane, exposing a slab of meat that Mercy prayed didn’t show any bone, but couldn’t get a stable enough look to see if it went as deep as that. His left ear was gone, and a terrible slash along his jawline showed the white, wet underpinning of his gums.

The Englishman said, “He must’ve gotten hit by a bit of that last tree.”

“Must’ve,” Mercy said. She pulled Mickey’s head into her lap and daubed the wound until it was mostly clean.

Ernie asked, “Can you help him?”

“Not much,” she confessed. “Here, help me get him comfortable.” She adjusted his body so that his oozing head rested against the older woman’s thigh. “Sorry,” she told her. “But I’ve got to get inside my bag. Give me a second.”

The woman might’ve given the nurse a second, but the line wouldn’t.

A cannonball shot across the road in front of them, blasting a straight and charred zone through the woods, across the two wheel ruts, and into the trees on the other side, where something was big enough to stop it. A second followed the first, then a third.

The horses screamed and reared, and Clinton wrestled with the reins, begging them with swears, threats, and promises to calm themselves and for God’s sake, keep pulling. One after another the horses found their feet and lunged, heaving the damaged cart forward again. But the axle was creaking dangerously, and Mickey wouldn’t stop bleeding, and in the empty spaces between the trees, gunfire was whizzing and plunking against trunks.

“We’re too heavy,” the copilot said, and withdrew to the farthest corner, away from the damaged axle. “The cart isn’t going to make it!”

“One more mile!” shouted Clinton. “We’re halfway to the rail lines; it only has to make it one more mile!”

“But it’s not gonna,” Mercy cried.

“Holy Jesus all fired in hell!” Clinton choked, just loudly enough for the nurse to hear him. She looked up to see where he was staring, and glimpsed something enormous moving alongside them, not quite keeping pace but ducking back and forth between the thick trunks of the trees that hid almost everything more than twenty yards away.

“What was that?” she asked loudly, forgetting her manners and her peril long enough to exclaim.

“They didn’t just bring the engine,” Clinton said to her, half over his shoulder while he tried to watch the road. “Those bastards brought a walker!”

“What’s a-?”

Another rock or a pothole sent the cart banging again, then the axle snapped, horrifying the horses and dragging the back end down to the ground, spilling out passengers and cargo alike. Mercy wrapped her torso around Mickey and her arm around the old woman who held him and stayed that way, clinging to a corner under the driver’s seat until the horses were persuaded to quit dragging the dead weight and let the thing haul to a stop.

Half off the road and half on it, the cart was splayed on its side much like the Zephyrhad wound up, only open and even more helpless looking.

“Goddammit!” Clinton swore as he climbed down from the cart in a falling, scrambling motion. He then set to work unhitching the horses. A swift hail of bullets burst from the trees. One of the horses was struck in a flank, and when it howled, it sounded like some exotic thing-something from another planet. It flailed upward onto two legs again, injured, but not mortally.

Mercy set to work directing the old couple, who had remained in what was left of the broken cart; and with a grunt she hefted Mickey up and slung him over her shoulder like a sack of feed. He was bigger than her by thirty pounds or more, but she was scared, and mad, and she wasn’t going to leave him. He sagged against her, nothing but weight, and blood soaked down the back of her cloak where his earless scalp bounced against her shoulder blade.

She staggered beneath him and hoisted him out of the cart’s wreckage, where she found one of the students-Dennis-standing in shock, in the middle of the road. “Good God Almighty!” She shoved him with her shoulder. “Get out of the road! Get down, would you? Keep yourself low!”

“I can’t,” he said as if his brain were a thousand miles away from the words. “I can’t find Larsen. I don’t see him. I . . . I have to find him. . . .”

“Find him from the ditch,” she ordered, and shoved him into the trees.

The captain was missing, too, and the copilot was helping with the horses, who were reaching shrieking heights of inconsolability. Robert was on point; he went to the elderly folks and took the woman’s hand to guide them both into some cover, and Ernie popped up from around the cart-looking more battered than even ten minutes previously, but in one piece, for the most part.

Mercy said, “Ernie,” with a hint of a plea, and he joined her, helping to shoulder Mickey. Soon the private hung between them, one arm around each neck, his feet dragging fresh trails into the dirt as they took him off the road.

“Where’s . . . ,” she started to ask, but she wasn’t even sure whom she was asking after. It was dark, and the lanterns were gone-God knew where-so a head count was virtually impossible.

“Larsen!” Dennis hollered.

Mercy snapped out with her free hand and took him by the shoulder. She said, “I’m going to hand Mickey over to you and Ernie right now, and you’re going to help carry him back into the woods. Where’s Mr. Clinton? Mr. Clinton?” she called, using her best and most authoritative patient-managing voice.

“Over here . . .”

He was, in fact, over there-still wrestling with the horses, guiding them off the road and doing his damnedest to assure them that things were all right, or that they were going to be all right, one of these days. “We can’t leave them,” he explained himself. “We can’t leave them here, and Bessie’s not hurt too bad-just winged. We can ride them. A couple of us, at least.”

“Fine,” Mercy told him. She also approved of assisting the horses, but she had bigger problems at the moment. “Which direction is the rail line?”

“West.” He pointed with a flap of his arm that meant barely more than nothing to Mercy.

“All right, west. Do the horses know the way back to the rails?”

“Do they . . . what now?”

“Mr. Clinton!” she hollered at him. “Do the horses know the way back to the rails, or to the front? If I slap one on the ass and tell it to run, will it run toward safety or back to some barn in Nashville?”

“Hell, I don’t know. To the rails, I suppose,” he said. “They’re draft horses, not cavalry. We rolled them in by train. If nothing else, they’ll run away from the line. They ain’t trained for this.”

“Mr. Clinton, you and Dennis here-you sling Mickey over the most able-bodied horse and make a run for it. Mrs. . . . Ma’am”-she turned to the old woman-“I’m sorry to say it, but I never heard your name.”

“Henderson.”

“Mrs. Henderson. You and Mr. Henderson, then, on the other horse. You think she can carry them?” she asked Clinton.

He nodded and swung the horses around, threading them through the trees and back toward Mercy. “They ain’t got no saddles, though. They were rigged for pulling, not for riding. Ma’am, you and your fellow here, can you ride ’em like this?”

Mrs. Henderson arched an eyebrow and said, “I’ve ridden rougher. Gentlemen, if you could help us mount, I’d be most grateful.”

“Where’s Larsen?” Dennis all but wailed. “I’m supposed to look out for him! Larsen! Larsen, where’d you go?”

Mercy turned around to see Dennis there, standing at the edge of the road like an enormous invitation. She walked up to him, grabbed him by the throat, and pulled him back into the trees and down to a seated position. “You’re going to get yourself killed, you dumb boy!”

On the other side of the road, somewhere thirty or forty yards back, things were going from bad to worse. What had started as intermittent but terrifying artillery had grown louder and more consistent, and there was a bass-line undercurrent to it that promised something even worse. Something impossibly heavy was moving with slow, horrible footsteps, pacing along the lines on the other side. She spotted it here and there, for a moment-then no more.

She forced herself to concentrate on the matters at hand.

One problem at a time. She could fix only one problem at a time.

Prioritize.

“Dennis, you listen to me. Get on that horse with Mickey, and hold him steady. Ride west until you hit the rails, and get him to some safety. You can ride a horse, can’t you?”

“But-”

“No but.” She jammed a finger up to his nose, then turned to Clinton. “Clinton, you’re an able-bodied man and you can walk or run the rest of the way, same as me. Ernie, can you still walk all right?”

“Yes ma’am. It’s just the hand, what’s all tore up.”

“Good. You, me, Clinton, and . . . where’s Mr. Copilot-?”

“His name is Richard Scott, but I don’t see where he’s gone,” Robert interjected.

“Fine. Forget about him, if he’s gonna run off like that. Has anyone seen the captain?”

“I think he fell out when the cart broke,” Ernie said.

“Right. Then. We’re missing Larsen, the captain, and the copilot. The Hendersons are on Bessie.” She waved at Mrs. Henderson, who was tangling her hands in the horse’s mane and holding her husband in front of her. She could barely reach around him, but she nodded grimly. “The Hendersons are riding Bessie, and Dennis will be riding the other horse, with Mickey. Is that everyone?” She began her litany again, pointing at each one in turn. “That leaves me, Ernie, Robert, Mr. Rand, and Clinton to find our own way to the rails, but we can do that, can’t we, gentlemen?”

“Larsen!” Dennis called once more.

This time she smacked him, hard across the face. He held his breath.

She said, “If you open your mouth once more, I’ll slap it clear into next Tuesday. Now hush yourself. I’m going to go find Larsen.”

“You are?”

“I am. You, on the other hand, are heading west, so help me God-if only to get you away from us, because you’re going to get us shot. Clinton, kindly help this fellow get on that horse and then the rest of us can get moving, too.”

Clinton nodded at her like a man who was accustomed to taking orders, then hesitated briefly, because he was not accustomed to taking orders from a woman. Then he realized that he didn’t have any better ideas, so he took Dennis by the arm, led him to the horse, and helped him aboard. The student did not look particularly confident in the absence of a saddle, but he’d make do.

“Don’t you let him fall!” Mercy commanded.

Clinton slapped both horses on the rear, and the beasts took off almost cheerfully, so delighted were they to be leaving the scene. The remaining members of the ragtag party had no time to discuss further strategy. No sooner had the horses disappeared between the trees, headed generally west, than the southern side of the fighting line met them at the road.

The soldiers rushed up with battle cries, leading carts with cannon, and crawling machines that carried antiaircraft guns modified to point lower, as necessary. The crawling machines moved like insects, squirting oil and hissing steam from their joints as they loped forward; and the cannon were no sooner stopped than braced, and pumped, and fired.