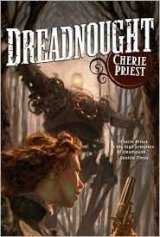

Текст книги "Dreadnought"

Автор книги: Cherie Priest

Соавторы: Cherie Priest

Жанр:

Стимпанк

сообщить о нарушении

Текущая страница: 17 (всего у книги 24 страниц)

“And you think it’s me?” Korman asked, patting himself on the chest. “Son,” he said, even though the captain was probably older than him, if only by a few years. “I’ve got better things to do with my time than to slow up a train that I very badly need. And, anyway, you can quit worrying about your spy. He’s dead.”

“What are you talking about?”

“It was Berry, don’t you get it? That boy may have hailed from Ohio, but he had heartstrings that went a lot farther south. You’re just lucky he wasn’t any better at spying. Blame it on his youth, I suppose. Did he know about the gold you’ve got in that next car?”

MacGruder flung a glare at Mercy, but she folded her arms and ignored it.

“Of course he knew about it. You saw him in there, propped up on it, shooting out at the meat-baskets and their riders.” But something in his voice betrayed an uncertainty. “At least, I thought he was shooting. Maybe he was picking bats out of the sky. Goddamn.”

The ranger went on. “Did he know about whatever’s in that back car?”

“I doubt it. But to think, I just sent him back there, giving him every excuse in the world to bust it open, find out, and spread the word around.”

Mercy said, “You told me you didn’t know if it was bodies or something stranger. If you ever said such a thing in front of him, he would’ve passed it along, don’t you think?”

“I’ll tell you what I think, Mrs. Lynch,” the captain said. “Rumor’s had it that you were in league with the Texian all this time. I tried to look the other way-”

Before he could hard-boil his sentiments into an accusation, she blurted out, “I’m from Virginia. I worked at the Robertson Hospital in Richmond. That’s the only thing I ever lied to you about. My husband was Phillip Lynch, and he died in the Andersonville camp, and I’m on my way to see my daddy.” Though she sat beside him, she slid her legs around so she could face him. “It’s the same for me as Mr. Korman. We just need to get west. Neither one of us would’ve done anything at all to slow this train or harm it. Neither one of us has anything to do with spying.”

Her words hung in the night-black air. Between the three of them, they gradually realized that no one was shooting anymore, except far away, and in what could only be described as a retreat.

As one, they rose up and went to the train’s south windows and pressed their faces to the panes where the glass hadn’t broken. Mercy said, with honest relief, “Look, they’re leaving!”

And Korman said, “Thank God.” Then he turned to the captain and said, “You, and me, and her-” He indicated Mercy. “We’re in this together now.”

“How you figure?” he asked.

“Because we’re all three being betrayed by somebody. I know my word won’t mean much, but let me tell you this: I knew one of the boys who led the early raid that didn’t go nowhere. They were just scouting, you knew it the same as I did. But I shot ’im a telegram back in Topeka, trying to get a bead on what’s going on here, and I’m hoping for a response in Denver. As a gesture of good faith, I’m willing to share that with you, and send that fellow a warning to leave the train be.”

“And why exactly would you do that?”

The ranger gritted his teeth and said, “All I want to do is get to Salt Lake City. This train will get me there faster than any other, and it’s in my best interest to see it arrive in one piece. Don’t be dense, man. I’m trying to help.”

The men stared each other down, until Mercy interjected, “Fellas, listen. All God’s children got a job to do here, and all any of us want is to head out west and to mind our own business. But I think we need to mind someone else’s business for a bit.”

The captain asked, “What do you mean by that?”

And she said, “I mean, I think we should find out what’s in the back of this train. Because if it’s a bigger secret and something more important than a few tons of gold and a whole passel of land deeds,” she let this information slide casually, “then Mr. Purdue is just about the last man on earth I trust to be in charge of it.”

“You’re suggesting that I disobey orders.”

“You were suggesting that Cyrus Berry do the same,” she countered, “when you sent him back there. You want to know; you’re just afraid to find out. But whatever’s back there, Purdue is willing to kill for it-and he’ll kill his way up the chain of command, I bet. Whatever it takes to sneak his treasure up to Boise.”

In the absence of bullets spitting every which-a-way, the train slowed from its breakneck pace into something more ordinary-not leisurely, but not straining like the engine was gobbling every bit of fuel it could burn, either. The silence that followed, without anyone shooting and without anyone in the passenger car at all, was broken only by the unrelenting wind whistling through the broken patches in the glass.

But off in the distance-terribly far away, so far that they couldn’t have seen it clearly even if the sun had been out-a tiny glimmer raced along the horizon line. And from that same position, miles and miles away, the cold prairie air brought a rumor of a tune, one long note held high and loud like the call of one train to another.

Mercy asked, “What’s that?” and pointed, even though they were all looking at the same thing, the same minuscule glowing dot that sailed smooth as a marble along some other path, somewhere far away.

Horatio Korman adjusted his hat, jamming it farther down on his head to fight the pull of the rushing air, and said, “Unless I miss my guess, Mrs. Lynch, I’d say that’s probably the Shenandoah.”

Sixteen

The Dreadnoughtpulled into Denver early the next morning and parked a few extra hours for repairs. Most of the passengers debarked, all rattled and some crying, with apologies from the Union and vouchers to take other trains to their destinations. Of the original occupants of Mercy’s car, only Theodora Clay and her indomitable aunt Norene Butterfield remained; and of the passengers who’d been present when the meat-baskets made their attack, only about a dozen opted to stick it out. Consequently, the train company would also be abandoning four passenger cars, leaving only three to house the soldiers and remaining scant passengers.

Those who remained were confined to the train while the repairs were made because the captain was insistent that they must get moving at the first possible instant after the repairs were done. The only exception was Horatio Korman, who was let off his car with the captain’s tacit approval, much to the astonishment and concern of the other enlisted men.

Purdue had stashed himself in the caboose, where he all but lived now. Like the other passengers, he stayed on board while the Denver crews replaced windows, reloaded ammunition bays, refilled boilers, and patched the most conspicuous bullet holes. He sat at that single portal to the train’s very back end and guarded it when he could, and had his right-hand man, Oscar Hayes, keep watch over it when Purdue was occasionally compelled to sleep. Most of the pretense of law and order and chain of command had been abandoned in the last twenty-four hours of the trip, and if Malverne Purdue had ever feigned any respect for the unit’s captain, his acting days were over.

While all these situations were simmering and settling, Theodora Clay came back to the second passenger car and sat across the sleeper compartment from Mercy, even though she and her aunt had moved to the other side of the aisle, given the reduction in the passenger load. She placed her hands on top of her knees, firmly gripping the fabric of her skirt as she leaned forward and said, “Things are going from bad to worse.”

“Yep,” Mercy replied carefully, for she suspected that Miss Clay was not making a social call.

“I’ve been talking to the captain,” she said. “And trying to talk to Mr. Purdue. You must be aware by now that he’s a madman. Did you hear he shot Cyrus Berry?”

“Yep.”

Her forehead wrinkled, then smoothed. “Oh yes. They said your friend the Texian was there when it occurred. I suppose he passed the information along. Well.” She released her grip on the dress and sat up straighter while she sorted out what else she ought to share. “Anyway, as I said. Regarding Mr. Purdue.”

“A madman.”

“An armed madman, even more delightfully. He won’t move, and he won’t take tea or coffee, and he just sits, with his chair beside the door and a Winchester lying across his lap and several other guns strapped all over himself. Overkill, I’d call it, but there you go. Sane men take a more moderated approach to these things.”

“He’s not reallycrazy,” Mercy told her. “He’s just got a job to do, and he’s real excited about doing it.”

Miss Clay said, “Be that as it may. Do you have the faintest clue what his job might be? Because no one seems to know what’s in the last car, except that it holds the bodies of dead soldiers. And I think we ought to investigate.”

“We? You mean, you and me?”

She said, “That’s right. You and I. For a brief and maddening minute I almost considered asking your Texian friend if he might be inclined to assist us, but for some reason or another, he seems to have vacated the train. I do pray he won’t be joining us again, but that’s neither here nor there.”

“He’ll be back. He’s picking up telegrams.”

“I’m sorry to hear it. Even so, he might’ve been just the man to barrel past Mr. Purdue, or to sneak past that other boy who does Mr. Purdue’s bidding. If nothing else, I doubt he’d have too many compunctions about shooting past the pair of them. Those Texians. Dreadful lot, the whole breed.”

“I’ve often said the same about Yankee women, but you don’t see me going on about it, now, do you?” Mercy retorted.

This shut down Miss Clay momentarily, but she chose not to read too far into the statement. After all, there were class distinctions among the northern regions same as in the southern regions, and everyone knew it. Either Miss Clay was choosing to believe she was being insulted by a Midwesterner, or she’d already concluded she dealt with a gray traitor and had come to terms with it, because she did not call attention to the remark.

Instead she said, “Come now, Mrs. Lynch. There’s no need to be rude. I want us to work together.”

The nurse asked, “And why is that?”

Theodora Clay leaned forward again, speaking softly enough that her aunt, napping nearby, would not be roused by her words. “Because I want to know what killed those lads.”

“I reckon it was a cannonball to the chest, or something similar. Or a missing arm or leg. Like as not, if there are real war veterans dead back there, that’s what killed them.”

She nodded. “That, or infection, or . . .” She dropped the whisper another degree. “Poison.”

“Poison?” Mercy responded, too loudly for Miss Clay’s liking.

She shrugged and waved her hands as if she wasn’t certain of where she was going, but the plan was forming and she was determined to exposit it. “Poison, or some kind of contamination. I . . . I overheard something.”

“Did you?”

“Yes, those Mexican inspectors, they-”

“Are they still on board?”

“Yes,” Miss Clay said quickly, eager to get back to her idea. “They’ve moved to the next car up. They were talking about some kind of illness or poison that they think might’ve contaminated their missing men. I know you spoke with them.”

“They might’ve mentioned it.” Or shemight’ve mentioned it, but she didn’t say so.

Nearly exasperated, Miss Clay said, “Mr. Purdue was talking to that fellow, that Mr. Hayes.”

“About the missing Mexicans?”

“Yes. He was reading a newspaper-while he was back there, like a toad in a hole-and I was only trying to get some breakfast. He was telling Mr. Hayes that something that could alter so many hundreds of people all at once would make a tremendous weapon, if that’s what had happened. And before long, if he had his way, the Union would be in a position to produce just such a weapon.”

It was Mercy’s turn to frown. “Turning a disease or a poison into a weapon? I’ve never heard of such a thing.”

“ Ihave,” Miss Clay informed her. “During the French and Indian war, the government gave smallpox-infected blankets to hostile tribes. It was cheaper and easier than exterminating them.”

“What a gruesome way of looking at it!”

“Gruesome indeed! It’s an army,Mrs. Lynch, not a schoolyard full of boys. It’s their job to destroy things and kill people in the name of their own population. They do what they must, and they do it as inexpensively as they can, and as efficiently as possible. What could be more insidious and efficient than an unseen contagion?”

Mercy lifted a finger to pretend to doodle on the table between them as she responded. “But the problem with an unseen contagion is obvious, ain’t it? You’re gonna infect your own folks with it, sure as you infect other people.”

“Clearly some amount of research and development would be required, but isn’t that what Mr. Purdue does on his own time, in order to justify his continued existence as a passenger on this train? He’s a scientist,and he’s guarding a scientific treasure trove. For the military,” she emphasized this final point.

“It sounds awful, but I don’t guess I’d put it past him.”

“Neither would I,” Miss Clay said with a set of her mouth that wasn’t quite a smile, but conveyed the fact that she thought that now she and the nurse might finally be on the same page. “And that’s why we must take this opportunity while the train is stationary, to sneak into that rear car and see what’s inside.”

Mercy’s eyebrows bounced up. “You can’t be serious.”

“Of course I can. I’ve even changed my shoes for the occasion.”

“Bully for you,” Mercy said. “What are you going to do? I’ve already done my best to persuade the captain to intervene. Shall you seduce your way past Mr. Purdue and-”

“Don’t be revolting. And please recall, I’ve requested your own involvement as well. It’ll be disgusting, no doubt. And it wouldn’t be necessary if that blasted captain would stand up to the hierarchy and insist for himself that the things under his purview are all known quantities. But alas, I can’t convince him to budge on the matter. Ridiculous man, and his ridiculous sense of duty.”

“He’s all right. You leave him alone.”

Miss Clay made a little sniff and said, “If you say so. Now, come on.” She changed the subject, rising to her feet. “You and I are going to perform some reconnaissance.”

“We’re going to do what?”

“We’re going to poke around, and let ourselves into that car.”

Mercy asked, “How? The doors are sealed and chained. You’ve seen that yourself, I bet, when we’ve stopped at stations and stretched our legs. And even if they weren’t, Mr. Purdue and his very large gun are standing between us and that car. Or, Mr. Hayes, as the case may be.”

“Think bigger. Think higher.” She pulled on a pair of thin calfskin gloves and fastened their buttons while she said, “We’ll go over. There’s an emergency hatch on the roof. It’s designed to let people out, not in,but unless I’m sorely mistaken, it will work both ways.” Finished with her gloves, she continued, “Here’s what we’ll do: We’ll go to the last passenger car, take the side ladder up to the roof, and crawl across the top of the caboose, then jump over to the final car.”

Mercy said, “You’re daft!” but she was already getting excited about the plan.

“I’m daft, and I’m going. And I require your medical . . .” She almost didn’t say it, but in the transparent hope that flattery might get her someplace, she finished with, “expertise.”

“Oh, for the love of God.”

“ Please,Mrs. Lynch. The repairmen are finished with the rear compartments, and they’ve moved on to the engine and the broken windows in the first car. We won’t be here more than another hour.”

Mercy said, “Fine,” folded her satchel up, and left it on her seat. She rose and adjusted the gunbelt she now wore more often than not and draped her cloak over her shoulders without raising the hood.

As she followed Theodora Clay out of their passenger car and onto the next one, she did not mention that their errand might prove to be a race against time. She did not tell her companion about the Shenandoah,the Confederate engine that had ridden a northwestern track in order to bring those meat-baskets up to the plains and unleash them on the Dreadnought. She did not mention that she had indeed been talking to the Texian, and that he believed the Shenandoahwas still following, tracking to the south and east, but closing ground, despite its defeat. If he was lucky, Horatio Korman was in the process of retrieving a telegram that would inform him of how correct his suspicions were. And if they were alllucky, it would say that the Shenandoahhad given up, turned around, and headed back down to Dallas.

Meanwhile, the engine halted in Denver for only a few hours when it ought to have stayed overnight for an inspection; because a telegram from Union intelligence had been waiting in Denver, no doubt warning of precisely this same possibility and urging haste in any repair work.

While the train sat there, grounded and undergoing the improvements that would keep it rolling the next thousand miles, Mercy Lynch followed Theodora Clay to the spot between the last passenger car and the caboose. It was strange to stand on the junction without the wind putting up a fight, but no stranger than watching Miss Clay scale the external ladder with casual quietness and then, from the top of the car, pivot on her knees and urge Mercy to join her.

When she reached the top rung, Miss Clay whispered, “Move slowly and be quiet. Discretion is the better part of valor in this instance. If we make too much noise, they’ll hear us inside.”

“Sure,” said Mercy, who then pulled herself up on top of the steel-and-tin roof, sliding on her belly like a seal and then climbing to an all-fours position. Her skirts muffled the knocking of her knees, and her wool gloves kept the worst of the frigid surface’s chill from getting through to her fingers. But even with the thick layers of clothes, she could feel the cold seeping up through the fabric, and onto her shins, and into her palms.

The nurse had the feeling that Denver was a gray, smoky place under the best of circumstances, and while the Dreadnoughtwas being addressed in its station, a layer of dirty snow hung over everything. It blurred the edges between buildings, sidewalks, streets, and interchanges, and it made the air feel somehow colder. Atop the caboose, which they very slowly traversed in inches that were gained in calculated shifts, slides, and steps, there was little snow except what had fallen since they’d stopped. This snow was a funny color, more like frozen smog than shaved ice. It collected between her fingers and soaked along her legs and elbows where it met her body heat.

Around the train, men hurried back and forth-most of them soldiers or mechanics, bringing sheets of glass and soldering equipment up to the front of the train; but over the edge Mercy could also spy a station manager with stacks of envelopes, folders, ticket stubs, and telegraph reports.

All she could do was pray that no one looked up.

Even if the women flattened themselves down, anyone standing close enough to the caboose could likely stand on tiptoe and see what they were doing. The crawl was torturous and time consuming, but in what felt like hours (but was surely only ten minutes) they had traversed the car and were prepared to lower themselves back down onto the next platform, the one between the caboose and the final car.

On her way down the ladder, Theodora Clay hissed, “Mind your step. And stay clear of the window.”

Mercy had every intention of following these suggestions to the letter. She slowly traced Miss Clay’s steps down the ladder, across the pass, and then up the next ladder, approximately as silently as a house cat wearing a ball dress. On her way to the top of the final car, she looked over her shoulder to peek through the caboose window, where she saw the back of Malverne Purdue’s head bobbing and jiggling. She thought he must be talking to someone she couldn’t see, and hoped that she wasn’t in the other speaker’s line of sight.

By the time she was situated and stable, Theodora Clay was already prodding at the edges of the emergency hatch, or ventilation hatch, or whatever the portal’s original purpose might have been. Mercy crept to her side and used the back of her hand to brush the small drifts of snow away from the hinges and seal. Before long, she spotted a latch.

Mercy angled her arm for better leverage and gave the latch a heave and a pull, which Theodora Clay assisted with when the nurse’s progress wasn’t fast enough to suit her. Between them, they forced the handle around and then heard the seal pop, its rubber fittings gasping open.

Theodora Clay asked, “Why would they seal it with rubber, like a canning jar?”

Mercy was already rocking back on her knees, her hand to her face. “To keep the cold in. Or . . . good God. To keep the smell contained! Lord Almighty, that’s . . . Ugh,” she said, lacking a word with the appropriate heft and reaching instead for a gagging noise.

Her companion didn’t do much better. She, too, covered her mouth and nose, then said from behind her hands, “The smell of death, of course. I’d think you’d be accustomed to it, working in a hospital like you have.”

“I’ll have you to know,” Mercy said, her words similarly muffled and choked. “We didn’t have thatmany men die on us. It was a very good hospital.”

“Must’ve been. Is there a ladder or anything to let us descend?”

“I don’t see one,” Mercy said, taking a deep breath of the comparatively fresh air outside, then dipping her head down low to get a better look. “And there’s more to that smell than just death.”

Inside, she saw only darkness; but as her eyes adjusted, she saw elongated forms that were surely coffins. Her breath fogged when she let it out, casting a small white cloud down into the interior. She sat back up and said, “I see caskets. And some crates. If there’s no better way, we could stack them up to climb back out again. But when they open the car in Boise, they’ll know someone got inside,” she concluded.

“Maybe. But do you really think anyone would believe it was us?”

“You’re probably right. And as for getting down . . .” She held her breath again and dropped her head inside for a look around. When she came back up for air, she said, “It’s no deeper than a regular car. If we hang from our hands, our feet’ll almost touch the floor.” Mercy said, “You first.”

Miss Clay nodded. “Certainly.”

She did not ask for any assistance, and Mercy didn’t offer any. It took some wrangling of clothing and some eye-watering adjustments to the interior air, but soon both women were inside, standing on a floor that was as cold as the roof above. The compartment was almost as dark as night, except for a strip of glowing green bulbs, the color of new apples, that lined the floor from end to end. They barely gave off any light at all, and seemed to blow most of their energy merely being present.

But the women used their feeble glow to begin a careful exploration of the narrow car, which was virtually empty except for the crates and the coffins. If the crates were labeled at all, Mercy couldn’t detect it; and the coffins themselves did not seem to have any identifying features either. There were no plaques detailing the names or ranks of the men within, only dark leather straps that buckled around each one. Each one also had a rubber seal like the hatch in the roof.

Mercy said, “I’m opening one up.”

“Wait.” Miss Clay stopped her, even as her hand went to one of the buckles. “What if it issome kind of contamination?”

“Then we’ll get sick and die. Look, on the floor over there. They’re coupler tools, but you can use one as a crowbar, in a pinch. Or you can see about opening some crates, if you’re getting cold feet. This was youridea, remember?”

“Yes, my idea,” Miss Clay said through chattering teeth.

“Ooh. Hang on,” Mercy stopped herself. “Before you start, let’s stack up a box or two so we can make a hasty exit, if it comes down to it.”

Miss Clay sighed heavily, as if this were all a great burden, but then agreed. “Very well. That’s the biggest one I see; we can start there. Could you help me? It’s awfully heavy.”

Mercy obliged, helping to shove the crate under the top portal, and then they man-hauled a smaller box on top of it, creating a brief but apparently sturdy stairway to the ceiling.

Miss Clay said, “There. Are you satisfied?”

“No. But it’ll have to do.”

Even though she’d been offered the alternative activity of checking the crates nearby, Theodora hung over Mercy’s shoulder while she unfastened the buckles and straps and reached for the clasps that would open the coffin.

Mercy said, “Before I lift this, you might wanna cover your mouth and nose.”

Miss Clay said, “It does nothing to offset the odor.”

“But there may be fumes in there that you don’t want to breathe,” she said, drawing up her apron and holding it up over her face in an impromptu mask. Then she worked her fingers under the clasps and freed them. They lifted with a burp of release.

More outrageous stench wafted up from the coffin, spilling and pooling as if whoever was lying inside had been breathing all this time, his breath had frozen into mist, and this mist was only now free to ooze tendril-like from the depths of this container. It collected around the women’s feet and coiled about their ankles.

Theodora Clay gave the lid a supplementary heave. It slid away from the coffin’s top, revealing a body lying within.

Mercy wished with all her might for something like the Texian’s small lighted device, but instead she was forced to wait for her eyes to adjust and for the cold fog to clear enough for her to see inside. As the man’s features came into focus, she gasped, clapping her apron’s corner even more tightly against her face.

Miss Clay did not gasp, but she was clearly intrigued. “He looks just awful,” she observed, though what she expected of a man who’d been dead for some weeks and kept in storage, Mercy wasn’t prepared to guess. “Is that . . .” She pointed at the loll of his neck and the drag of his skin as it began to droop away from his bones. “Is all that normal?”

The nurse’s words were muffled when she replied, “No. No, it’s not normal at all. But I’ve seen it before,” she added.

“Seen what?”

Mercy had had enough. “Close it! Just close the lid and buckle it up again. I don’t need to see any more!”

Theodora Clay frowned, looked back down into the coffin’s interior, and said, “But that’s ridiculous. You haven’t even frisked him for bullet wounds or broken-”

“I said close it!” she nearly shrieked, and toppled backwards away from it.

Perhaps out of surprise, or perhaps only to appease her companion, Miss Clay obliged, drawing the lid back into place and pulling the buckles, seals, and clasps into their original positions. “Well, if you got everything you needed to know from a glance-”

“I did. I saw plenty. That man, he didn’t die in battle.” Mercy turned away and looked longingly at the stack of crates that led to freedom above, and to the light of a dull gray sky. Then she looked back at the crates that took up the places where the coffins had not been placed. She noted the coupler tools, and she picked one of them up.

“Yes,” her companion said, and selected another tool that might be used as a prybar. “We should also examine these before we leave.”

Mercy was already at work on the nearest one. Since it was placed near the square of light from the open hatch above, she was relatively certain that there were no markings present to be deciphered. She pressed her long metal instrument into the most obvious seam and wedged her arm down hard. This gesture was greeted with the splitting sound of nails being drawn unwillingly out of boards, and the puff of crisp, fragile sawdust being disturbed.

Miss Clay was having more difficulty with her own crate, so she abandoned it to see what Mercy had turned up. “What on earth are thosethings?” she asked.

Mercy reached inside and pulled out a glass mason jar filled with a gritty yellow powder. She shook it and the powder moved like a sludge, as if it had been contaminated by damp. She said, “It must be sap.”

“I’m afraid you must be mistaken. That looks nothing at all like-”

“Not treesap,” Mercy cut her off. “ Sap. It’s . . . it’s a drug that’s becoming real common with men on the front. I’ve heard of it before, and I’ve seen men who abused it bad, but I’ve never seen it. So I might be wrong, but I bet I’m not.”

“Why would you make that bet?”

“Because that man over there-” She used the prybar to point at the coffin. “-he died from this stuff. He’s got all the marks of a man who used it too much, right into the grave.”

“What about the rest of them?”

“What about them?”

“We should see how they died.”

The nurse replaced the jar and plunged her hands down through the sawdust, feeling for anything else. She turned up another jar or two, some labeled samples in scientific tubes, and what looked like the sort of equipment one might use to distill alcohol. She said, “Waste of time. Look at all this equipment.”

“I’m looking at it, but I have no idea what any of it does, or what it is.”

“It looks like a still, sort of. For brewing up moonshine, only not exactly. I think the army’s trying to figure out what makes the drug work, and maybe turn it into a poison, or a weapon, like you said. I think they’ve gotten hold of as much of the yellow sap as they could scare up, and now they’re trying to figure out how they can make a whole passel of it.” The words came tumbling out of her mouth, quivering with her jaw as she did her best not to shiver. “This is all so wrong. We’ve got to get out of here, before we breathe in too much of this junk. Come on, Miss Clay. Let’s go. Me and you, now. We’ve got to leave this alone.”

“Leave it alone?”

“For now, anyway,” she said as she spun around and placed her hands on the large base crate that would lead the way up and out. “There’s nothing we can do for these men, and right now we don’t have proof of anything, just ideas and thoughts. Let’s get out of here so we can think. We can talk about it back in the car, if no one catches us and throws us in jail.”